Tales from My Professional Life Nurul Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

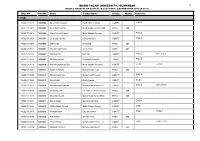

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Khan, Adeeba Aziz (2015) Electoral institutions in Bangladesh : a study of conflicts between the formal and the informal. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23587 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Electoral Institutions in Bangladesh: A Study of Conflicts Between the Formal and the Informal Adeeba Aziz Khan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Law 2015 Department of Law SOAS, University of London I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University, Gopalganj Department of International Relations Syllabus for Bachelor of Social Science (Hons) Session: 2015- 2016 to 2018- 2019 1st Year 1st Semester, Examination-2016 Course Course Title Contact hours per week Credits No. IR 101 Introduction to International Relations 3 3 IR 102 History of International Relations 3 3 IR 103 Ideas and Issues in Political Science 3 3 IR 104 Contemporary Global Issues 3 3 IR 105 Principles of Economics 3 3 IR 106 Bangabandhu in International Relations 3 3 IR 119 Viva Voce 2 Total Credits 20 1st Year 2nd Semester, Examination-2016 Course No. Course Title Contact hours per week Credits IR 151 History of Bangladesh 3 3 IR 152 Ideologies in World Affair 3 3 IR 153 International Institutions 3 3 IR 154 Fundamentals of Sociology 3 3 IR 155 The Economy of Bangladesh 3 3 IR 156 Academic English Writing 2 2 IR 169 Viva Voce 2 Total Credits 19 2nd Year 1st Semester, Examination-2017 Course No. Course Title Contact hours per week Credits IR 201 Major Political Ideas of the West and the Orient 3 3 IR 202 Media and Mass Communication 3 3 IR 203 Refugees, Migrants and the Displaced 3 3 IR 204 Theories of International Relations 3 3 IR 205 Politics and Government in Bangladesh 3 3 IR 229 Viva Voce 2 Total Credits 17 2nd Year 2nd Semester, Examination-2017 Course No. Course Title Contact hours per week Credits IR 251 International Political Economy 3 3 IR 252 Media Maneuvering and World Politics 3 3 IR 253 Theories and Problems of Ethnicity and 3 3 Nationalism IR 254 International Law 3 3 IR 255 Jurisprudence 2 2 IR 279 Viva Voce 2 Total Credits 16 3rd Year 1st Semester, Examination-2018 Course No. -

Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollection Launched in Kolkata | the Daily Star

18/02/2016 Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollection launched in Kolkata | The Daily Star Home City 12:00 AM, January 22, 2016 / LAST MODIFIED: 03:22 AM, January 22, 2016 Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollection launched in Kolkata 19 Shares Eminent economist Rehman Sobhan discusses his new book "Untranquil Recollection, the Years of Fulfillment" with guests during the launching event at the National Library in Kolkata on Wednesday. Indian film star Sharmila Thakur, left, Nobel laureate Prof Amartya Sen, middle, among others, were present at the publication ceremony. Photo: collected Staff Correspondent Nobel laureate Prof Amartya Sen lauded economist Rehman Sobhan for his notable contribution to http://www.thedailystar.net/city/rehmansobhansuntranquilrecollecitonlaunchedkolkata205474 1/4 18/02/2016 Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollection launched in Kolkata | The Daily Star the self-reliance of Bangladesh's economy and introducing Bangladesh to the global arena at the publication ceremony of Rehman Sobhan's book "Untranquil Recollection, the Years of Fulfillment" at the National Library in Kolkata on Wednesday. "Bangladesh's progress is better than India in many sectors, and those who read the book will know more about Bangladesh," said Amartya Sen, according a report by the daily Prothom Alo. Rehman Sobhan said the book is not about the history of the independence of Bangladesh, rather how he observed Bangladesh's Liberation War. "I was born in Kolkata and studied at Saint Xavier's College there. Then, I went to Cambridge where I met Prof Amartya Sen," reminisced the author. "From Cambridge, I came back to Dhaka in 1956 and then came in close contact with Bangabandhu. -

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 18 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL

18 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021310011 3000002 Syed Afaq Hussain Syed Amin Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310001 3000003 Syed Atif Hussain Syed Sajid Hussain Shah PASS 430 110021310004 3000004 Mahr Ahmad Kamal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310006 3000005 Shahzad Ahmed Ashiq Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310007 3000006 Wali Khan Khowazik PASS 441 110021310013 3000007 Muhammad Ehsan Juma Khan PASS 437 110021310014 3000008 Mujahid Din Roz Din COMPT. ENG:II ENG-LIT:II 110021310015 3000009 Mehtab arshad Arshad Mehmood COMPT. ENG:II 110021310018 3000010 Mahr Muhammad Ijlal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ECO:I ECO:II 110021310021 3000011 Sammar Abbas Muhammad Ismail PASS 436 110021310022 3000012 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310026 3000013 Anas Ayaz Ayaz Ahmad COMPT. ECO:I 110021310027 3000014 Muhammad Shahzad Muhammad khursheed COMPT. ENG:II APP-PSY:II 110021310029 3000015 Shahab U Din Ch Zaheer Ud Din Ahmed PASS 384 110021310031 3000016 Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Sultan Khan PASS 453 110021310033 3000017 Sohail Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal COMPT. ENG:II 110021310034 3000018 Malik Waqar Ahmed Malik Iftikhar Ahmad COMPT. ENG:I 110021310035 3000019 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider COMPT. ENG:I ENG:II 110021310036 3000020 Arif Zaman Mehran Khan PASS 434 110021310038 3000021 Fahad Raza Muhammad Muslimeen COMPT. ENG:I ENG-LIT:II 110021310039 3000022 Mubasher Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz PASS 423 19 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. -

Courses Taught at Both the Undergraduate and the Postgraduate Levels

Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts Department of History SYLLABUS Preface The Department of History, Jadavpur University, was born in August 1956 because of the Special Importance Attached to History by the National Council of Education. The necessity for reconstructing the history of humankind with special reference to India‘s glorious past was highlighted by the National Council in keeping with the traditions of this organization. The subsequent history of the Department shows that this centre of historical studies has played an important role in many areas of historical knowledge and fundamental research. As one of the best centres of historical studies in the country, the Department updates and revises its syllabi at regular intervals. It was revised last in 2008 and is again being revised in 2011.The syllabi that feature in this booklet have been updated recently in keeping with the guidelines mentioned in the booklet circulated by the UGC on ‗Model Curriculum‘. The course contents of a number of papers at both the Undergraduate and Postgraduate levels have been restructured to incorporate recent developments - political and economic - of many regions or countries as well as the trends in recent historiography. To cite just a single instance, as part of this endeavour, the Department now offers new special papers like ‗Social History of Modern India‘ and ‗History of Science and Technology‘ at the Postgraduate level. The Department is the first in Eastern India and among the few in the country, to introduce a full-scale specialization on the ‗Social History of Science and Technology‘. The Department recently qualified for SAP. -

Advisory Council WI

ICC-01/05-01/08-466-Anx2 31-07-2009 1/2 IO PT Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice International Advisory Council Members Professor Hilary Charlesworth Director of the Centre for International Governance and Justice Australian National University Australia Professor Rhonda Copelon International Women’s Human Rights Law Clinic City University of New York Law School United States of America Associate Professor Tina Dolgopol Flinders University Australia Professor Paula Escarameia 1 Institute of Social and Political Sciences, Technical University of Lisbon Portugal Lorena Fries 2 President of Corporación Humanas Chile Sara Hossain Advocate, Supreme Court of Bangladesh Barrister, Dr Kamal Hossain & Associates Bangladesh Rashida Manjoo 3 Law Faculty University of Cape Town South Africa Professor Mary Robinson 4 Chancellor of Dublin University School of Law, Trinity College, Dublin Department of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University Ireland Nazhat Shameem Barrister of the Inner Temple and the High Court of Fiji Fiji 1 Professor Paula Escarameia is also a member of the International Law Commission of the United Nations. 2 Lorena Fries is also a candidate for the CEDAW Committee 2010. 3 Rashida Manjoo is also the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women 4 Professor Mary Robinson is also a former President of the Republic of Ireland 1990-1997 and former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 1997-2002. ICC-01/05-01/08-466-Anx2 31-07-2009 2/2 IO PT Dr. Heisoo Shin Former Vice-Chairperson of the CEDAW Committee South Korea Pam Spees Attorney at Law United States of America Associate Professor Dubravka Zarkov Institute of Social Studies The Netherlands Professor Eleonora Zieliñska Faculty of Law and Administration Institute of Penal Law Warsaw University Poland . -

Genocide and Mass Violence: Theories, Traumas, Trials and Testimonies

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE On GENOCIDE AND MASS VIOLENCE: THEORIES, TRAUMAS, TRIALS AND TESTIMONIES Special Conference Room, Nabab Nawab Ali Chowdhury Senate Bhaban, University of Dhaka Organized by: Centre for Genocide Studies, University of Dhaka PROGRAMME Thursday, March 24, 2016 Inaugural Session 10.00 am to 10.10 am Welcome and opening remarks by Dr. Imtiaz Ahmed Professor, Department of International Relations & Director, Centre for Genocide Studies, University of Dhaka 10.10 am to 10.20 am Keynote Address by Dr. Kamal Hossain Former Minister of Law (1972-73) & Lawyer 10.20 am to 10.30 am Speech by Chief Guest Mr. Asaduzzaman Noor Honorable Minister of Cultural Affairs, People’s Republic of Bangladesh 10.30 am to 10.40 am Remarks by Chairperson Professor Dr. AAMS Arefin Siddique Vice Chancellor, University of Dhaka 10.40 am to 10.50 am Vote of thanks by Professor Dr. Delwar Hossain Department of International Relations, University of Dhaka 10.50 am to 11.00 am SESSION BREAK Plenary Session on Theories of Genocide and Mass Violence Chairperson: Advocate Sultana Kamal, Executive Director, Ain-O-Shalish Kendro Designated Discussants: Professor Ehsanul Haque, Chair, Department of International Relations, University of Dhaka Dr. Ayesha Banu, Associate Professor, Department of Women and Gender Studies, University of Dhaka 11.0 am to 11.25 am Dr. Bina D’Costa, Senior Research Fellow and Director of Studies, Department of International Relations, Australian National University Rethinking Genocide Theories: Emotions and the Logics of Mass -

Mujibur: You Know the History of My Country. Its Condition After the War Was Likened to That of Germany in 1945

DECLASSIFIED A/ISS/IPS, Department of State E.O. 12958, as amended October 11, 2007 MEMORANDUM THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: President Gerald R. Ford His Excellency Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Prime Minister of Bangladesh Dr. Kamal Hossain, Foreign Minister Ambassador M. Hossain Ali Lt. General Brent Scowcroft, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs DATE AND TIME: Tuesday - October 1, 1974 3:00 p.m. PLACE: The Oval Office The White House [The press was admitted briefly for photos. There was a discussion of pipe tobacco and Mrs. Ford's condition. The press was ushered out. ] President: It was a shock to us. We had to make the decision for the operation, then wait for them to determine malignancy, and so forth. Mujibur: I sincerely hope she is out of danger. President: Yes, the prognosis cannot be certain, but only two nodes out of 30 were malignant. It is good to have you here. It is the first time an American President has met with the head of state of Bangladesh. Mujibur: Yes. I am happy to have the opportunity to talk with you about my people. President: We are happy to do what we can for all countries. Mujibur: You know the history of my country. Its condition after the war was likened to that of Germany in 1945. I want to thank you for your help to us. Before the war we were divided by India. The capital was all in DECLASSIFIED A/ISS/IPS, Department of State E.O. 12958, as amended October 11, 2007 the west. -

Hunger and Entitlements

RESEARCH FOR ACTION HUNGER AND ENTITLEMENTS AMARTYA SEN WORLD INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS RESEARCH UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY WORLD INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS RESEARCH Lal Jayawardena, Director The Board of WIDER: Saburo Okita, Chairman Pentti Kouri Abdlatif Y. Al-Hamad Carmen Miro Bernard Chidzero I. G. Patel Mahbub ul Haq Heitor Gurgulino Albert O. Hirschman de Souza (ex officio) Lal Jayawardena (ex officio) Janez Stanovnik Reimut Jochimsen WIDER was established in 1984 and started work in Helsinki in the spring of 1985. The principal purpose of the Institute is to help identify and meet the need fur policy-oriented socio-economic research on pressing global and development prob- lems and their inter-relationships. The establishment and location of WIDER in Helsinki have been made possible by a generous financial contribution from the Government of Finland. The work of WIDER is carried out by staff researchers and visiting scholars and through networks of collaborating institutions and scholars in various par's of the world. WIDER's research projects are grouped into three main themes: I Hunger and poverty - the poorest billion II Money, finance and trade - reform for world development III Development and technological transformation - the management of change WIDER seeks to involve policy makers from developing countries in its research efforts and to draw specific policy lessons from the research results. The Institute continues to build up its research capacity in Helsinki and to develop closer contacts with other research institutions around the world. In addition to its scholarly publications, WIDER issues short, non-technical reports aimed at policy makers and their advisers in both developed and developing countries. -

Fazlul Huq, Peasant Politics and the Formation of the Krishak Praja Party (KPP)

2 Fazlul Huq, Peasant Politics and the Formation of the Krishak Praja Party (KPP) In all parts of India, the greater portion of the total population is, and always has been, dependent on the land for its existence and subsistence. During the colonial rule, this was absolutely true in the case of Bengal as a whole and particularly so of its eastern districts. In this connection, it should be mentioned here that the Muslim masses even greater number than the Hindus, were more concentrated in agriculture which is clearly been reflected in the Bengal Census of 1881: “………..while the husbandmen among the Hindus are only 49.28 per cent, the ratio among the Muslims is 62.81 per cent”.1 The picture was almost the same throughout the nineteenth century and continued till the first half of the twentieth century. In the different districts of Bengal, while the majority of the peasants were Muslims, the Hindus were mainly the landowning classes. The Census of 1901 shows that the Muslims formed a larger portion of agricultural population and they were mostly tenants rather than landlords. In every 10,000 Muslims, no less than 7,316 were cultivators, but in the case of the Hindus, the figure was 5,555 amongst the same number (i.e. 10,000) of Hindu population. But the proportion of landholders was only 170 in 10,000 in the case of Muslims as against 217 in the same number of Hindus.2 In the district of Bogra which was situated in the Rajshahi Division, the Muslims formed more than 80% of the total population. -

The Kargil Adventure and Its Political Consequences Abstract

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) Vol. IV, No. IV (Fall 2019) | Page: 38 – 44 IV).06 - The Kargil Adventure and Its Political Consequences Muhammad Shakeel PhD. Scholar, Department of Pakistan Studies, The Islamia University Akhtar Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. Associate Professor, Department of Pakistan Studies, The Islamia Aftab Ahmad Gilani University Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Professor (Rtd), Department of Pakistan Studies, The Islamia Khurshid Ahmad University Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. This paper studies the pre and post Kargil war events. It also elaborates the calculation and Abstract miscalculations of Kargil adventure from the top military brass and the Kargil clique. This paper also describes the question of civil military relations in Pakistan and actual corridor of the decision http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV making. It also Provides Knowledge about the plan of Kargil war, doctrine of secrecy, the aftermath of that adventure, the big bang Key Words between the civil-military leadership, the failure of diplomacy, the URL: Kargil, Kashmir, Military, impact of Kargil war on political system. This paper also highlighted the attempt to get Kargil at the rate of Kashmir. It is Civilian leadership, Siachen, assessed that the kagril episode had some precious consequences Religious Parties, Party related to the battlefield, warfare and the supremacy of army as IV).06 | - Politics an institution. This paper also showed the activities happened on the freeze heights of Kargil seriously affect, politics and civil- military relations in Pakistan. JEL Classification: IOK, LOC, COAS 10.31703/gssr.2019(IV Introduction DOI: The Kargil complex generally consists of rugged and fragile hills.