Duress and the Underlying Felony Russell Shankland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

Chapter 8. Final Instructions: Defenses and Theories of Defense

Chapter 8. Final Instructions: Defenses and Theories of Defense 8.01 Theory of Defense 8.02 Alibi 8.03 Duress (Coercion) 8.04 Justification (Necessity) 8.05 Entrapment 8.06 Insanity 8.07 Voluntary Intoxication (Drug Use) 8.01 Theory of Defense Comment The defendant has a constitutional right to raise a legally acceptable defense and to present evidence in support of that defense. See, e.g., Taylor v. Illinois, 484 U.S. 400, 408-09 (1988); Chambers v. Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284, 294-95 (1973); Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 18-19 (1967); United States v. Pohlot, 827 F.2d 889, 900-01 (3d Cir. 1987). When a defense is raised and supported by the law and the evidence, the jury should be instructed on the matter. See, e.g., United States v. Davis, 183 F.3d 231, 250 (3d Cir. 1999) (“A defendant is entitled to an instruction on his theory of the case where the record contains evidentiary support for it.”); Government of Virgin Islands v. Carmona, 422 F.2d 95, 99 (3d Cir. 1970) (“As long as there is an evidentiary foundation in the record sufficient for the jury to entertain a reasonable doubt, a defendant is entitled to an instruction on his theory of the case.”). In United States v. Hoffecker, 530 F.3d 137, 176-77 (3d Cir. 2008), the Third Circuit held that the trial court had properly refused to give the requested “theory of defense” instructions, because they were merely statements of the defense’s factual arguments. The court reasoned: “A defendant is entitled to a theory of defense instruction if (1) he proposes a correct statement of the law; (2) his theory is supported by the evidence; (3) the theory of defense is not part of the charge; and (4) the failure to include an instruction of the defendant's theory would deny him a fair trial.” United States v. -

People V Gillis, Unpublished Opinion Per Curiam of the Court of Appeals, Issued

Michigan Supreme Court Lansing, Michigan Chief Justice: Justices: Clifford W. Taylor Michael F. Cavanagh Elizabeth A. Weaver Marilyn Kelly Opinion Maura D. Corrigan Robert P. Young, Jr. Stephen J. Markman FILED APRIL 5, 2006 PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN, Plaintiff-Appellant, v No. 127194 JOHN ALBERT GILLIS, Defendant-Appellee. _______________________________ BEFORE THE ENTIRE BENCH MARKMAN, J. We granted leave to appeal to consider whether our state’s first-degree murder statute permits a felony-murder conviction “in the perpetration of” a first- or second-degree home invasion in which the homicide occurs several miles away from the dwelling and several minutes after defendant departed from the dwelling. Following a jury trial, defendant was convicted of two counts of first- degree felony murder, MCL 750.316(1)(b), with home invasion in the first degree, MCL 750.110a, as the predicate felony. Defendant appealed the convictions, asserting that he was no longer “in the perpetration” of home invasion at the time of the automobile collision that killed the victims. The Court of Appeals concluded that the accident was not “part of the continuous transaction of or immediately connected to the home invasion[,]” and, therefore, vacated the convictions and remanded for a new trial on the charges of second-degree murder. People v Gillis, unpublished opinion per curiam of the Court of Appeals, issued August 17, 2004 (Docket No. 245012), slip op at 3. We conclude that “perpetration” encompasses acts by a defendant that occur outside the definitional elements of the predicate felony and includes acts that occur during the unbroken chain of events surrounding that felony. -

1091026, People V. Ephraim

THIRD DIVISION August 17, 2011 2011 IL App (1st) 091026-U No. 1-09-1026 NOTICE: This order was filed under Supreme Court Rule 23 and may not be cited as precedent by any party except in the limited circumstances allowed under Rule 23(e)(1). IN THE APPELLATE COURT OF ILLINOIS FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, ) Appeal from the ) Circuit Court of Plaintiff-Appellee, ) Cook County. ) v. ) No. 08 CR 6405 ) DONZELL EPHRAIM, ) Honorable Evelyn B. Clay, ) Judge Presiding. Defendant-Appellant. ) Murphy, J., delivered the judgment of the court. Quinn, P.J., and Neville, J., concurred in the judgment. O R D E R HELD: The trial court did not err in finding defendant guilty of unlawful use of a weapon by a felon despite his assertion of a necessity defense, where the court did not improperly place the burden of proof upon defendant but made a legal assessment of whether that defense had been stated. ¶ 1 Following a bench trial, defendant Donzell Ephraim was convicted of unlawful use of a weapon by a felon and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment. On appeal, defendant contends that the trial court erred by placing the burden upon him to prove his affirmative defense of necessity. ¶ 2 At trial, police officer Peter Haritos testified that, at about 11:45 p.m. on March 18, 2008, he stopped a car that he had just seen pass through an intersection in disregard of a red traffic 1-09-1026 signal. The car, driven by defendant with no other occupants, stopped within seconds of Officer Haritos' signal to stop. -

Investigation of Armed Home Invasion Robberies Leads to Arrest of 5 Suspects

Palos Verdes Estates Police Department Press Release Mark Velez Chief of Police Investigation of armed home invasion robberies leads to arrest of 5 suspects On March 2, 2018, Palos Verdes Estates Police Department officers responded to a report of an armed home invasion robbery in the 700 block of Via La Cuesta. Officers and detectives arrived and documented this violent crime, examined forensic evidence and started an investigation. On July 8, 2018, PVEPD officers responded to another report of an armed home invasion robbery, which oc- curred in the 1300 block of Via Coronel. PVEPD officers and detectives again responded. Our detec- tives analyzed evidence from both scenes and believed both crimes were committed by the same suspects. Through an intense analysis of evidence and data, our detectives were able to identify 5 suspects who they believed to be associated with a South Los Angeles gang. With the assistance of the Tor- rance Police Department, hundreds of hours of surveillance was conducted and additional infor- mation was developed. Our detectives contacted other agencies who had similar home invasion rob- beries. PVEPD detectives developed enough evidence to believe this robbery crew was responsible for an additional 6 home invasion robberies committed in various cities throughout Los Angeles county. These cities included Rancho Palos Verdes, La Habra Heights, La Canada, Playa Del Rey and Palmdale. The estimated loss of these robberies was 1 million dollars. After this intense, fo- cused investigation and collaboration with allied agencies and the LA County District Attorney’s Of- fice, PVEPD detectives obtained arrest and search warrants. -

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal Release 20, September 2019 NOTICE TO USERS: THE FOLLOWING SET OF UNANNOTATED MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS ARE BEING MADE AVAILABLE WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER, MATTHEW BENDER & COMPANY, INC. PLEASE NOTE THAT THE FULL ANNOTATED VERSION OF THESE MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS IS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE FROM MATTHEW BENDER® BY WAY OF THE FOLLOWING LINK: https://store.lexisnexis.com/categories/area-of-practice/criminal-law-procedure- 161/virginia-model-jury-instructions-criminal-skuusSku6572 Matthew Bender is a registered trademark of Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. Instruction No. 2.050 Preliminary Instructions to Jury Members of the jury, the order of the trial of this case will be in four stages: 1. Opening statements 2. Presentation of the evidence 3. Instructions of law 4. Final argument After the conclusion of final argument, I will instruct you concerning your deliberations. You will then go to your room, select a foreperson, deliberate, and arrive at your verdict. Opening Statements First, the Commonwealth's attorney may make an opening statement outlining his or her case. Then the defendant's attorney also may make an opening statement. Neither side is required to do so. Presentation of the Evidence [Second, following the opening statements, the Commonwealth will introduce evidence, after which the defendant then has the right to introduce evidence (but is not required to do so). Rebuttal evidence may then be introduced if appropriate.] [Second, following the opening statements, the evidence will be presented.] Instructions of Law Third, at the conclusion of all evidence, I will instruct you on the law which is to be applied to this case. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana

Case 2:15-cv-01226-SM-SS Document 117 Filed 05/16/16 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA KEVIN JORDAN CIVIL ACTION Plaintiff VERSUS NO. 15-1226 ENSCO OFFSHORE COMPANY SECTION: “E” (1) Defendant ORDER AND REASONS Before the Court is Plaintiff Kevin Jordan’s motion to strike allegations of fraud in the proposed pre-trial order.1 The motion is opposed.2 For the reasons that follow, the motion to strike is GRANTED. Plaintiff moves to strike Defendant ENSCO Offshore Company’s allegations of fraud in the pre-trial order. Plaintiff argues the allegations of fraud first appeared in the pre-trial order, having not been raised in any of Defendant’s answers or prior filings.3 For that reason, Plaintiff contends the defense of fraud has been waived and cannot now be asserted by Defendant. Fraud is classified as an affirmative defense under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(c)(1).4 Rule 8(c) requires that affirmative defenses must be affirmatively pleaded in the answer or raised as a cause of action in a counterclaim; otherwise, the defense is deemed waived.5 In the parties’ proposed pre-trial order, the Defendant lists as a contested issue of fact: “Whether Kevin Jordan is committing a fraud on Ensco in making this claim for 1 R. Doc. 81. 2 R. Doc. 87. 3 R. Doc. 81-1 at 1. 4 See also Callon Petroleum Co. v. Frontier Ins. Co., No. Civ.A. 01-1502, 2002 WL 31819127, at *2 (E.D. La. -

Home Invasion Robbery

Problem-Specific Guides Series Problem-Oriented Guides for Police No. 70 Home Invasion Robbery Justin A. Heinonen and John E. Eck Problem-Oriented Guides for Police Problem-Specific Guides Series No. 70 Home Invasion Robbery Justin A. Heinonen John E. Eck This project was supported by cooperative agreement #2010-CK-WX-K005 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement of the product by the author(s) or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of this publication. Given that URLs and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s) nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. © 2012 Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, Inc. The U.S. Department of Justice reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable license to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and authorize others to use, this publication for Federal Government purposes. This publication may be freely distributed and used for noncommercial and educational purposes. www.cops.usdoj.gov ISBN: 978-1-932582-16-1 February 2013 Contents Contents About the Problem-Specific Guides Series. 1 Acknowledgments. 5 The Problem of Home Invasion Robbery. 7 What This Guide Does and Does Not Cover. -

Defendants' Answer to Plaintiffs' First Amended Class Action Complaint

Case 3:03-cv-01840-CRB Document 62-1 Filed 01/22/2004 Page 1 of 16 1 DENNIS J. HERRERA, State Bar #139669 City Attorney 2 JOANNE HOEPER, State Bar #114961 Chief Trial Attorney 3 INGRID M. EVANS, State Bar # 179094 DAVID B. NEWDORF, State Bar #172960 4 Deputy City Attorneys Fox Plaza 5 1390 Market Street, Sixth Floor San Francisco, California 94102-5408 6 Telephone: (415) 554-3884 Facsimile: (415) 554-3837 7 E-Mail: [email protected] 8 Attorneys for Defendants CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO, 9 SAN FRANCISCO SHERIFF'S DEPARTMENT and SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY SHERIFF MICHAEL HENNESSEY 10 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 MARY BULL, JONAH ZERN, and all Case No. C03-1840 CRB others similarly situated, 14 DEFENDANTS’ ANSWER TO Plaintiffs, PLAINTIFFS' FIRST AMENDED 15 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT AND vs. DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 16 CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN 17 FRANCISCO, SAN FRANCISCO SHERIFF'S DEPARTMENT, SAN 18 FRANCISCO COUNTY SHERIFF MICHAEL HENNESSEY, IN HIS 19 INDIVIDUAL AND OFFICIAL CAPACITY, AND SAN FRANCISCO 20 COUNTY SHERIFF'S DEPUTIES DOES 1 THROUGH 150, 21 Defendants. 22 23 24 Come now defendants City and County of San Francisco and San Francisco County 25 Sheriff Michael Hennessey, in his official capacity (collectively "answering defendants" or 26 "defendants") (San Francisco Sheriff's Department was erroneously sued and is a subdivision of 27 the City and County of San Francisco) and answer Plaintiffs' First Amended Class Action 28 Complaint and Demand for Jury Trial as follows: Answer to First Amended Complaint 1 N:\LIT\LI2003\031697\00219588.DOC USDC No. -

Is That a Fact? Recent Defamation Decisions of the Supreme Court Of

Volume XVII, Number V Summer 2014 Is That a Fact? Recent false, but defamatory, that is, it must ‘tend so to harm the reputation of another as to lower him in Defamation Decisions the estimation of the community or to deter third persons from associating or dealing with him.’”3 of the Supreme Court Stated differently, “merely offensive or unpleasant of Virginia statements” are not defamatory; rather, defamatory statements “are those that make the plaintiff appear by Dannielle Hall-McIvor odious, infamous, or ridiculous.”4 Determining whether a statement is one of fact 2. Cashion v. Smith: subjective statement, or opinion seems straightforward. A fact can be insinuation, or rhetorical hyperbole? proven false. An opinion depends on the speaker’s viewpoint and cannot be proven false. Although Defendants in defamation cases frequently claim describing the difference between fact and opinion that their statements are not defamatory because the is easy, differentiating between them in an actual statements were true, were statements of opinion, defamation case can be tricky. or were made in a protected context. The Supreme Court provided a detailed analysis of these defenses The Supreme Court’s recent defamation cases in Cashion v. Smith, 286 Va. 327, 749 S.E. 2d 526 provide much-needed help, offering guidance on (2013). In Cashion, the Supreme Court considered the elements of—and the defenses to—defamation whether a trauma surgeon’s allegedly defamatory claims. Although not marking a change in Virginia statements about an anesthesiologist’s treatment law, the detailed and fact-specific analyses in these Is ThaT a FacT? — cont’d on page 3 cases will help practitioners differentiate between fact and opinion in defamation cases. -

Case 2:16-Cv-00476-NBF Document 33 Filed 09/08/16 Page 1 of 10

Case 2:16-cv-00476-NBF Document 33 Filed 09/08/16 Page 1 of 10 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA DANIELLE MORRISON, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. 16-476 v. ) ) Hon. Nora Barry Fischer CHATHAM UNIVERSITY ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION I. Introduction Pending before the Court in this matter is a Partial Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s First Amended Complaint filed by Defendant Chatham University. (Docket No. 13). Having considered Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint, (Docket No. 9); Defendant’s motion to dismiss and supporting briefing, (Docket Nos. 13, 14); Plaintiff’s response in opposition, (Docket No. 19); Defendant’s reply, (Docket No. 20); and oral argument presented by the parties on August 29, 2016, (Docket No. 28), Defendant Chatham University’s motion to dismiss is GRANTED. II. Background This matter arises from Plaintiff’s enrollment as a doctoral student at Chatham University. The following facts are alleged in the Amended Complaint, which the Court will accept as true for the sole purpose of deciding the pending motion. Plaintiff, an African-American woman, graduated college with distinction and earned a Master’s of Science degree in Counseling Psychology. (Docket No. 9 ¶ 1). In 2009, Plaintiff enrolled as a student at Chatham University to obtain a doctoral degree in Counseling 1 Case 2:16-cv-00476-NBF Document 33 Filed 09/08/16 Page 2 of 10 Psychology. (Id.). After her initial success and progress in the program, Plaintiff was denied benefits that were given to similarly situated white students and was disparaged based upon her race. -

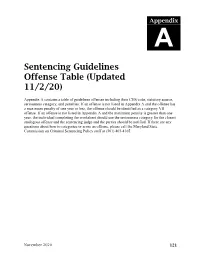

Sentencing Guidelines Offense Table (Updated 11/2/20)

Appendix A Sentencing Guidelines Offense Table (Updated 11/2/20) Appendix A contains a table of guidelines offenses including their CJIS code, statutory source, seriousness category, and penalties. If an offense is not listed in Appendix A and the offense has a maximum penalty of one year or less, the offense should be identified as a category VII offense. If an offense is not listed in Appendix A and the maximum penalty is greater than one year, the individual completing the worksheet should use the seriousness category for the closest analogous offense and the sentencing judge and the parties should be notified. If there are any questions about how to categorize or score an offense, please call the Maryland State Commission on Criminal Sentencing Policy staff at (301) 403-4165. November 2020 121 INDEX OF OFFENSES Abuse & Other Offensive Conduct ......................... 1 Kidnapping & Related Crimes .............................. 33 Accessory After the Fact ......................................... 2 Labor Trafficking ................................................... 33 Alcoholic Beverages ................................................ 2 Lotteries ................................................................. 33 Animals, Crimes Against ......................................... 3 Machine Guns ........................................................ 34 Arson & Burning ...................................................... 3 Malicious Destruction & Related Crimes ............. 34 Assault & Other Bodily Woundings .......................