Sovereign Wealth Funds Ending United States Protectionism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Open Letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime

An open letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Finance, from fourteen leading New Zealand international aid agencies No-one is safe until we are all safe 28 April 2020 Dear Prime Minister Ardern, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister Peters, and Finance Minister Robertson, We thank you for the unprecedented steps your government has taken to protect people in New Zealand from the coronavirus and its impacts. Today, we ask that you extend assistance to people in places far less able to withstand this pandemic. With your inspiring leadership and guidance, here in New Zealand we have accepted the need for radical action to stop the coronavirus and are coping as best we can. Yet, as you know, even with all your government has done to support people through these hard times, people remain worried about their health and their jobs. Like here, family life has been turned upside down across the world. It’s hard to imagine families crammed into refugee camps in Iraq and Syria, or in the squatter settlements on the outskirts of Port Moresby, living in close quarters, with no clean water close by, no soap, and the knowledge that there will be little help from struggling public health systems. We’ve all become experts at hand washing and staying at home as we try to stop coronavirus and save lives. It is not easy, but we know how crucial it is to stop the virus. What would it be like trying to do this at a single tap in your part of the refugee camp, that 250 other people also rely on? This is the reality for more than 900,000 people in Cox’s Bazaar refugee camp in Bangladesh. -

The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint As Finance Minister to Balance the Budget?

1188 Discussion Papers Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung 2012 The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint as Finance Minister to Balance the Budget? Beate Jochimsen and Sebastian Thomasius Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views of the institute. IMPRESSUM © DIW Berlin, 2012 DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research Mohrenstr. 58 10117 Berlin Tel. +49 (30) 897 89-0 Fax +49 (30) 897 89-200 http://www.diw.de ISSN print edition 1433-0210 ISSN electronic edition 1619-4535 Papers can be downloaded free of charge from the DIW Berlin website: http://www.diw.de/discussionpapers Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin are indexed in RePEc and SSRN: http://ideas.repec.org/s/diw/diwwpp.html http://www.ssrn.com/link/DIW-Berlin-German-Inst-Econ-Res.html The perfect finance minister: Whom to appoint as finance minister to balance the budget? Beate Jochimsen Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Sebastian Thomasius∗ Free University of Berlin Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) February 2012 Abstract The role and influence of the finance minister within the cabinet are discussed with increasing prominence in the recent theoretical literature on the political economy of budget deficits. It is generally assumed that the spending ministers can raise their reputation purely with new or more extensive expenditure programs, whereas solely the finance minister is interested to balance the budget. Using a dynamic panel model to study the development of public deficits in the German states between 1960 and 2009, we identify several personal characteristics of the finance ministers that significantly influence budgetary performance. -

Financial Freak Show

Financial freak show September 15, 2008 – The S&P/TSX Capped Financials Index has not retested its mid- July low of 154. In fact, the index, which tracks Canada’s major financial services companies, closed last Friday at 184, up 19.5% from July’s low. It’s a sign that investors believe that the worst could well be over for the big Canadian banks, most of which have taken sizable writedowns of US subprime mortgage-related debt. A price floor seems to have developed for the financials, and compared with the financial freak show unfolding south of the border, Canadian banks now appear as bastions of financial probity. But that’s no reason to gloat. Most Canadian banks’ balance sheets were fouled with the same sort of junk that’s bedevilling much of the US financial sector just now, but not to the same degree. They cleaned it up in a hurry, but let’s not forget that with one or two exceptions – Scotiabank and Toronto-Dominion Bank leap to mind – Canadian banks fell into the same trap that their US counterparts did. So no kudos for these guys – at least not until they restore shareholder value and demonstrate a return to the principles of solid bank management. On the other hand, the financial drama that continues to unfold in the south 49 has taken on the epic proportions of high Shakespearean tragedy. With much rending of garments and falling on swords the fourth-largest US investment bank, Lehman Brothers Holdings, descended into the banker’s hell of non-confidence last week, as the Korea Development Bank abandoned a possible deal that would have kept Lehman afloat. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

xxxui CHRONOLOGY í-i: Sudan. Elections to a Constituent Assembly (voting postponed for 37 southern seats). 4 Zambia. Basil Kabwe became Finance Minister and Luke Mwan- anshiku, Foreign Minister. 5-1: Liberia. Robert Tubman became Finance Minister, replacing G. Irving Jones. 7 Lebanon. Israeli planes bombed refugee camps near Sidon, said to contain PLO factions. 13 Israel. Moshe Nissim became Finance Minister, replacing Itzhak Moda'i. 14 European Communities. Limited diplomatic sanctions were imposed on Libya, in retaliation for terrorist attacks. Sanctions were intensified on 22nd. 15 Libya. US aircraft bombed Tripoli from UK and aircraft carrier bases; the raids were said to be directed against terrorist head- quarters in the city. 17 United Kingdom. Explosives were found planted in the luggage of a passenger on an Israeli aircraft; a Jordanian was arrested on 18 th. 23 South Africa. New regulations in force: no further arrests under the pass laws, release for those now in prison for violating the laws, proposed common identity document for all groups of the population. 25 Swaziland. Prince Makhosetive Dlamini was inaugurated as King Mswati III. 26 USSR. No 4 reactor, Chernobyl nuclear power station, exploded and caught fire. Serious levels of radio-activity spread through neighbouring states; the casualty figure was not known. 4 Afghánistán. Mohammad Najibollah, head of security services, replaced Babrak Karmal as General Secretary, People's Demo- cratic Party. 7 Bangladesh. General election; the Jatiya party won 153 out of 300 elected seats. 8 Costa Rica. Oscar Arias Sánchez was sworn in as President. Norway. A minority Labour government took office, under Gro 9 Harlem Brundtland. -

GOVERNMENT of MEGHALAYA, OFFICE of the CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong ***

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA, OFFICE OF THE CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong *** New Delhi | Sept 9, 2020 | Press Release Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad K. Sangma and Deputy Chief Minister Prestone Tynsong today met Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in New Delhi and submitted memorandum requesting the Ministry of Finance to incentivise national banks and prioritize the setting up of new bank branches in rural areas to increase the reach of banking system in the State. Chief Minister also submitted a memorandum requesting the Government of India to increase Meghalaya’s share of central taxes. The Union Minister was also apprised on the overall financial position of Meghalaya. After meeting Union Finance Minister, Chief Minister and Dy Chief Minister also met Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur and discussed on way forward for initiating externally funded World Bank & New Development Bank projects in the state. He was also apprised of the 3 externally aided projects that focus on Health, Tourism & Road Infrastructure development in the State. Chief Minister and Dy CM also met Union Minister for Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Dairying Giriraj Singh and discussed prospects and interventions to be taken up in the State to promote cattle breeding, piggery and fisheries for economic growth and sustainable development. The duo also called on Minister of State Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises, Arjun M Meghwal and discussed various issues related to the introduction of electric vehicles, particularly for short distance public transport. Later in the day, Chief Minister met Union Minister for Minority Affairs, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi as part of his visit to the capital today. -

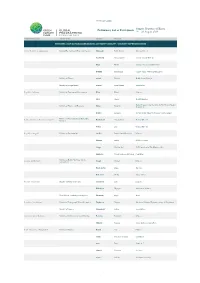

GCF Global Programming Conference

#GCFconnections Songdo, Republic of Korea Preliminary List of Participants 19 – 23 August 2019 COUNTRY/ORGANIZATION MINISTRY/AGENCY LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE MINISTERS / GCF NATIONAL DESIGNATED AUTHORITY (NDA/FP) / COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVES Islamic Republic of Afghanistan National Environmental Protection Agency Maiwandi Schah Zaman Director General Hoshmand Ahmad Samim Climate Change Director Khan Hamid Advisor - International Relations Bakhshi M.Solaiman Climate Finance Mechanisms Expert Ministry of Finance Salemi Wazhma Health Sector Manager Minitry of Foreign Affairs Atarud Abdul Hakim Ambassador Republic of Albania Ministry of Tourism and Environment Klosi Blendi Minister Çuçi Ornela Deputy Minister Budget Programming Specialist In The General Budget Ministry of Finance and Economy Muka Brunilda Department Demko Majlinda Adviser of The Minister of Finance and Economy Ministry of Environment and Renewable People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Boukadoum Abderrahmane General Director Energies Nouar Laib General Director Republic of Angola Ministry of Environment Coelho Paula Cristina Francisco Minister Massala Arlette GCF Focal Point Congo Mariano José GCF Consultant of The Minister office Lumueno Witold Selfroneo Da Gloria Consultant Minister of Health, Wellness and the Antigua and Barbuda Joseph Molwyn Minister Environment Black-Layne Diann Director Robertson Michai Policy Officer Republic of Armenia Ministry of Nature Protection Grigoryan Erik Minister Hakobyan Hayrapet Assistant to Minister Water Resources Management Agency Pirumyan -

Financial Statement

GOVERNMENT OF BARBADOS FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND BUDGETARY PROPOSALS 2011 PRESENTED BY HON. CHRISTOPHER P. SINCKLER MINISTER OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC AFFAIRS Tuesday 16th August, 2011 1 Mr. Speaker Sir, it is with a chastened outlook yet calmed assurance that I rise to deliver to this Honourable House the Financial Statement and Budgetary Proposal for 2011. I am chastened Sir, not only by the enormity of the task that confronts me as Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs, as it does indeed the entire Government and people of Barbados, but equally as well by the massive responsibility which has been imposed on us to safely navigate our country through this most challenging period of the country’s history. Lesser men and women would have shirked from this responsibility in favour of more certain waters and a less contentious atmosphere. Surely at times Mr. Speaker, my own human frailty has led me, as I am sure it has led many others across this country, in moments of weakness to ask: why me? But for those of us on whom God Almighty has vested the burden of leadership in trying times, it is expected that we do as the Apostle Paul instructed the early Christians in his letter to the Corinthians and I quote: “Keep alert, stand Firm in your faith, be courageous, be strong” That is why for my own part, as I walk this treacherous path of uncertain economic times, I do so with a resilience to do what is mine to do. For I know that my strength also comes from the certainty that I am not walking this path alone. -

The Rise of Latham & Watkins

The M&A journal - Volume 7, Number 5 The Rise of Latham & Watkins In 2006, Latham & Watkins came in fifth in terms of deal value.” the U.S. for deal value in Thompson Financial’s Mr. Nathan sees the U.S. market as crucial. league tables and took second place for the num- “This is a big part of our global position,” he says, ber of deals. “Seven years before that,” says the and it is the Achilles’ heel of some of the firm’s firm’s Charles Nathan, global co-chair of the main competitors. “The magic circle—as they firm’s Mergers and Acquisitions Group, “we dub themselves—Allen & Overy, Freshfields, weren’t even in the top twenty.” Latham also Linklaters, Clifford Chance and Slaughters— came in fourth place for worldwide announced have very high European M&A rankings and deals with $470.103 million worth of transactions, global rankings, but none has a meaningful M&A and sixth place for worldwide completed deals presence in the U.S.,” Mr. Nathan says. Slaughter Charles Nathan worth $364.051 million. & May, he notes, has no offices abroad. What is behind the rise of Latham & Watkins Similarly, in the U.S., Mr. Nathan says that his in the world of M&A? firm has a much larger footprint than its domestic “If you look back to the late nineties,” Mr. rivals. “Unlike all the other major M&A firms,” Nathan says, “Latham was not well-recognized he says, “we have true national representation. as an M&A firm. We had no persona in M&A. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Regulation of the Finance Minister Number 80/Pmk.03

FINANCE MINISTER OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA COPY REGULATION OF THE FINANCE MINISTER NUMBER 80/PMK.03/2009 ON THE SURPLUS RECEIVED OR GAINED BY A NON PROFIT AGENCY OR INSTITUTION IN EDUCATION AND/OR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT THAT ARE EXEMPTED FROM INCOME TAX THE FINANCE MINISTER, Having : That in implementing the provision of Article 4 paragraph (3) letter m considered of Law Number 7 of 1983 on Income Tax as amended several times and last by Law Number 36 of 2008, it is necessary to enact a Regulation of the Finance Minister on the Surplus Received or Gained by a Non-profit Agency or Institution in Education and/or Research and Development that are Exempted from Income Tax; Having : 1. Law Number 6 of 1983 on General Provisions and Procedures for observed Taxation (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 1983 Number 49, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 3262) as amended several times and last by Law Number 28 of 2007 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 2007 Number 85, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 4740); 2. Law Number 7 of 1983 on Income Tax (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 1983 Number 50, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia number 3263) as amended several times and last by Law Number 36 of 2008 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 2008 Number 133, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 4893); 3. Presidential Decree Number 20/P of 2005; HAS DECIDED: To enact : THE SURPLUS RECEIVED OR GAINED BY NON- PROFIT AGENCIES OR INSTITUTIONS IN EDUCATION AND/OR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT THAT ARE EXEMPTED FROM INCOME TAX. -

Cabinet Structure and Fiscal Policy Outcomesejpr 1914 631..653

European Journal of Political Research 49: 631–653, 2010 631 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01914.x Cabinet structure and fiscal policy outcomesejpr_1914 631..653 JOACHIM WEHNER Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK Abstract. A central explanation of fiscal performance focuses on the structure of the cabinet. However, the partisan context of cabinet decisions remains under-explored, the findings are based on small samples and the variables of interest are often poorly opera- tionalised. Using a new dataset of spending ministers and partisan fragmentation in the cabinets of 58 countries between 1975 and 1998, this study finds a strong positive association between the number of spending ministers and budget deficits and expenditures, as well as weaker evidence that these effects increase with partisan fragmentation. The outcome of the annual budget process is crucial in the competition among cabinet ministers for political standing. As one minister sums up the effect of budgetary decisions on his career prospects1: ‘If that bugger in transport gets more money than me, I look like a loser.’ Such individual-level incentives to boost spending can have profound aggregate consequences (Niskanen 1971; Von Hagen & Harden 1995). Cross-national studies find that cabinet size or the number of spending ministers affects fiscal performance (Volkerink & De Haan 2001; Perotti & Kontopoulos 2002; Woo 2003; Ricciuti 2004). However, this literature suffers from several shortcomings. First, it gives insufficient consideration to the possible interaction between the number of spending ministers and the partisan context of bargaining over the budget. Second, sample size is limited and the extent to which the findings can be generalised beyond a few industrialised democracies remains unclear. -

Copy Regulation of the Finance Minister Number 113/ Pmk.02/ 2009 on Oil and Gas Account by the Grace of the One Almighty God the Finance Minister

FINANCE MINISTER THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA COPY REGULATION OF THE FINANCE MINISTER NUMBER 113/ PMK.02/ 2009 ON OIL AND GAS ACCOUNT BY THE GRACE OF THE ONE ALMIGHTY GOD THE FINANCE MINISTER, Having considered : a. that for the purpose of collecting the Government’s share from oil and gas upstream business activities, the Finance Minister as the State General Treasury has opened the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia; b. that to provide the legal certainty over the settlement of Government’s obligation concerning the oil and gas upstream business activities through the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia, it is necessary to stipulate the provisions on the disbursement of funds from the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia ; c. that based upon the consideration as referred to in letter a and letter b, it is necessary to enact the Regulation of the Finance Minister on Oil and Gas Account. Having observed : 1. Law Number 8 of 1983 on Value Added Tax on Goods and Services and Tax on the Sales of Luxury Items (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 51 of 1983, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 3246) as amended several times, and last by Law Number 18 of 2000 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 128 of 2000, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 3986); 2.