Cabinet Structure and Fiscal Policy Outcomesejpr 1914 631..653

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Open Letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime

An open letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Finance, from fourteen leading New Zealand international aid agencies No-one is safe until we are all safe 28 April 2020 Dear Prime Minister Ardern, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister Peters, and Finance Minister Robertson, We thank you for the unprecedented steps your government has taken to protect people in New Zealand from the coronavirus and its impacts. Today, we ask that you extend assistance to people in places far less able to withstand this pandemic. With your inspiring leadership and guidance, here in New Zealand we have accepted the need for radical action to stop the coronavirus and are coping as best we can. Yet, as you know, even with all your government has done to support people through these hard times, people remain worried about their health and their jobs. Like here, family life has been turned upside down across the world. It’s hard to imagine families crammed into refugee camps in Iraq and Syria, or in the squatter settlements on the outskirts of Port Moresby, living in close quarters, with no clean water close by, no soap, and the knowledge that there will be little help from struggling public health systems. We’ve all become experts at hand washing and staying at home as we try to stop coronavirus and save lives. It is not easy, but we know how crucial it is to stop the virus. What would it be like trying to do this at a single tap in your part of the refugee camp, that 250 other people also rely on? This is the reality for more than 900,000 people in Cox’s Bazaar refugee camp in Bangladesh. -

The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint As Finance Minister to Balance the Budget?

1188 Discussion Papers Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung 2012 The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint as Finance Minister to Balance the Budget? Beate Jochimsen and Sebastian Thomasius Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views of the institute. IMPRESSUM © DIW Berlin, 2012 DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research Mohrenstr. 58 10117 Berlin Tel. +49 (30) 897 89-0 Fax +49 (30) 897 89-200 http://www.diw.de ISSN print edition 1433-0210 ISSN electronic edition 1619-4535 Papers can be downloaded free of charge from the DIW Berlin website: http://www.diw.de/discussionpapers Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin are indexed in RePEc and SSRN: http://ideas.repec.org/s/diw/diwwpp.html http://www.ssrn.com/link/DIW-Berlin-German-Inst-Econ-Res.html The perfect finance minister: Whom to appoint as finance minister to balance the budget? Beate Jochimsen Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Sebastian Thomasius∗ Free University of Berlin Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) February 2012 Abstract The role and influence of the finance minister within the cabinet are discussed with increasing prominence in the recent theoretical literature on the political economy of budget deficits. It is generally assumed that the spending ministers can raise their reputation purely with new or more extensive expenditure programs, whereas solely the finance minister is interested to balance the budget. Using a dynamic panel model to study the development of public deficits in the German states between 1960 and 2009, we identify several personal characteristics of the finance ministers that significantly influence budgetary performance. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

xxxui CHRONOLOGY í-i: Sudan. Elections to a Constituent Assembly (voting postponed for 37 southern seats). 4 Zambia. Basil Kabwe became Finance Minister and Luke Mwan- anshiku, Foreign Minister. 5-1: Liberia. Robert Tubman became Finance Minister, replacing G. Irving Jones. 7 Lebanon. Israeli planes bombed refugee camps near Sidon, said to contain PLO factions. 13 Israel. Moshe Nissim became Finance Minister, replacing Itzhak Moda'i. 14 European Communities. Limited diplomatic sanctions were imposed on Libya, in retaliation for terrorist attacks. Sanctions were intensified on 22nd. 15 Libya. US aircraft bombed Tripoli from UK and aircraft carrier bases; the raids were said to be directed against terrorist head- quarters in the city. 17 United Kingdom. Explosives were found planted in the luggage of a passenger on an Israeli aircraft; a Jordanian was arrested on 18 th. 23 South Africa. New regulations in force: no further arrests under the pass laws, release for those now in prison for violating the laws, proposed common identity document for all groups of the population. 25 Swaziland. Prince Makhosetive Dlamini was inaugurated as King Mswati III. 26 USSR. No 4 reactor, Chernobyl nuclear power station, exploded and caught fire. Serious levels of radio-activity spread through neighbouring states; the casualty figure was not known. 4 Afghánistán. Mohammad Najibollah, head of security services, replaced Babrak Karmal as General Secretary, People's Demo- cratic Party. 7 Bangladesh. General election; the Jatiya party won 153 out of 300 elected seats. 8 Costa Rica. Oscar Arias Sánchez was sworn in as President. Norway. A minority Labour government took office, under Gro 9 Harlem Brundtland. -

GOVERNMENT of MEGHALAYA, OFFICE of the CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong ***

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA, OFFICE OF THE CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong *** New Delhi | Sept 9, 2020 | Press Release Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad K. Sangma and Deputy Chief Minister Prestone Tynsong today met Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in New Delhi and submitted memorandum requesting the Ministry of Finance to incentivise national banks and prioritize the setting up of new bank branches in rural areas to increase the reach of banking system in the State. Chief Minister also submitted a memorandum requesting the Government of India to increase Meghalaya’s share of central taxes. The Union Minister was also apprised on the overall financial position of Meghalaya. After meeting Union Finance Minister, Chief Minister and Dy Chief Minister also met Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur and discussed on way forward for initiating externally funded World Bank & New Development Bank projects in the state. He was also apprised of the 3 externally aided projects that focus on Health, Tourism & Road Infrastructure development in the State. Chief Minister and Dy CM also met Union Minister for Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Dairying Giriraj Singh and discussed prospects and interventions to be taken up in the State to promote cattle breeding, piggery and fisheries for economic growth and sustainable development. The duo also called on Minister of State Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises, Arjun M Meghwal and discussed various issues related to the introduction of electric vehicles, particularly for short distance public transport. Later in the day, Chief Minister met Union Minister for Minority Affairs, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi as part of his visit to the capital today. -

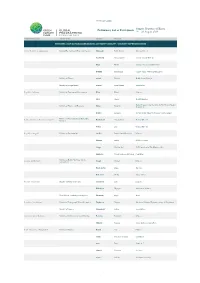

GCF Global Programming Conference

#GCFconnections Songdo, Republic of Korea Preliminary List of Participants 19 – 23 August 2019 COUNTRY/ORGANIZATION MINISTRY/AGENCY LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE MINISTERS / GCF NATIONAL DESIGNATED AUTHORITY (NDA/FP) / COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVES Islamic Republic of Afghanistan National Environmental Protection Agency Maiwandi Schah Zaman Director General Hoshmand Ahmad Samim Climate Change Director Khan Hamid Advisor - International Relations Bakhshi M.Solaiman Climate Finance Mechanisms Expert Ministry of Finance Salemi Wazhma Health Sector Manager Minitry of Foreign Affairs Atarud Abdul Hakim Ambassador Republic of Albania Ministry of Tourism and Environment Klosi Blendi Minister Çuçi Ornela Deputy Minister Budget Programming Specialist In The General Budget Ministry of Finance and Economy Muka Brunilda Department Demko Majlinda Adviser of The Minister of Finance and Economy Ministry of Environment and Renewable People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Boukadoum Abderrahmane General Director Energies Nouar Laib General Director Republic of Angola Ministry of Environment Coelho Paula Cristina Francisco Minister Massala Arlette GCF Focal Point Congo Mariano José GCF Consultant of The Minister office Lumueno Witold Selfroneo Da Gloria Consultant Minister of Health, Wellness and the Antigua and Barbuda Joseph Molwyn Minister Environment Black-Layne Diann Director Robertson Michai Policy Officer Republic of Armenia Ministry of Nature Protection Grigoryan Erik Minister Hakobyan Hayrapet Assistant to Minister Water Resources Management Agency Pirumyan -

Financial Statement

GOVERNMENT OF BARBADOS FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND BUDGETARY PROPOSALS 2011 PRESENTED BY HON. CHRISTOPHER P. SINCKLER MINISTER OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC AFFAIRS Tuesday 16th August, 2011 1 Mr. Speaker Sir, it is with a chastened outlook yet calmed assurance that I rise to deliver to this Honourable House the Financial Statement and Budgetary Proposal for 2011. I am chastened Sir, not only by the enormity of the task that confronts me as Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs, as it does indeed the entire Government and people of Barbados, but equally as well by the massive responsibility which has been imposed on us to safely navigate our country through this most challenging period of the country’s history. Lesser men and women would have shirked from this responsibility in favour of more certain waters and a less contentious atmosphere. Surely at times Mr. Speaker, my own human frailty has led me, as I am sure it has led many others across this country, in moments of weakness to ask: why me? But for those of us on whom God Almighty has vested the burden of leadership in trying times, it is expected that we do as the Apostle Paul instructed the early Christians in his letter to the Corinthians and I quote: “Keep alert, stand Firm in your faith, be courageous, be strong” That is why for my own part, as I walk this treacherous path of uncertain economic times, I do so with a resilience to do what is mine to do. For I know that my strength also comes from the certainty that I am not walking this path alone. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Regulation of the Finance Minister Number 80/Pmk.03

FINANCE MINISTER OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA COPY REGULATION OF THE FINANCE MINISTER NUMBER 80/PMK.03/2009 ON THE SURPLUS RECEIVED OR GAINED BY A NON PROFIT AGENCY OR INSTITUTION IN EDUCATION AND/OR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT THAT ARE EXEMPTED FROM INCOME TAX THE FINANCE MINISTER, Having : That in implementing the provision of Article 4 paragraph (3) letter m considered of Law Number 7 of 1983 on Income Tax as amended several times and last by Law Number 36 of 2008, it is necessary to enact a Regulation of the Finance Minister on the Surplus Received or Gained by a Non-profit Agency or Institution in Education and/or Research and Development that are Exempted from Income Tax; Having : 1. Law Number 6 of 1983 on General Provisions and Procedures for observed Taxation (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 1983 Number 49, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 3262) as amended several times and last by Law Number 28 of 2007 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 2007 Number 85, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 4740); 2. Law Number 7 of 1983 on Income Tax (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 1983 Number 50, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia number 3263) as amended several times and last by Law Number 36 of 2008 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 2008 Number 133, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic Indonesia Number 4893); 3. Presidential Decree Number 20/P of 2005; HAS DECIDED: To enact : THE SURPLUS RECEIVED OR GAINED BY NON- PROFIT AGENCIES OR INSTITUTIONS IN EDUCATION AND/OR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT THAT ARE EXEMPTED FROM INCOME TAX. -

Copy Regulation of the Finance Minister Number 113/ Pmk.02/ 2009 on Oil and Gas Account by the Grace of the One Almighty God the Finance Minister

FINANCE MINISTER THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA COPY REGULATION OF THE FINANCE MINISTER NUMBER 113/ PMK.02/ 2009 ON OIL AND GAS ACCOUNT BY THE GRACE OF THE ONE ALMIGHTY GOD THE FINANCE MINISTER, Having considered : a. that for the purpose of collecting the Government’s share from oil and gas upstream business activities, the Finance Minister as the State General Treasury has opened the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia; b. that to provide the legal certainty over the settlement of Government’s obligation concerning the oil and gas upstream business activities through the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia, it is necessary to stipulate the provisions on the disbursement of funds from the Ministry of Finance Account for Proceeds from Oil Production Sharing Work Agreement Numbered 600.000411 at Bank Indonesia ; c. that based upon the consideration as referred to in letter a and letter b, it is necessary to enact the Regulation of the Finance Minister on Oil and Gas Account. Having observed : 1. Law Number 8 of 1983 on Value Added Tax on Goods and Services and Tax on the Sales of Luxury Items (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 51 of 1983, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 3246) as amended several times, and last by Law Number 18 of 2000 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 128 of 2000, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 3986); 2. -

Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Revenue Central Board of Direct Taxes

Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Revenue Central Board of Direct Taxes New Delhi, 22nd June, 2021 PRESS RELEASE Finance Ministry interaction with tax professionals, other stakeholders and Infosys on issues in the new Income Tax Portal A meeting was held between senior officials of the Finance Ministry and Infosys on 22.06.2021 on issues in the new Income Tax Portal. The meeting was presided over by Hon’ble FM, Smt. N. Sitharaman. MoS(Finance), Shri Anurag Singh Thakur also participated in the meeting. The interaction was attended by Shri Tarun Bajaj, Secretary Revenue, Shri J. B. Mohapatra, Chairman, CBDT, Smt. Anu J. Singh, Member(L & Systems), CBDT and other senior officers of CBDT. Infosys was represented by its MD & CEO, Shri Salil Parekh and COO, Shri Praveen Rao and other members of their team. The meeting was also attended by 10 tax professionals from across the country, including representatives of ICAI and All India Federation of Tax Practitioners (AIFTP). The new efiling portal 2.0 of Income Tax Department (incometax.gov.in) went live on 07.06.2021. Since its launch, there were numerous glitches in the functioning of the new portal. Taking note of the grievances voiced on social media by taxpayers, tax professionals and other stakeholders, the Hon’ble Finance Minister had also flagged the issues to the vendor M/s Infosys, calling upon them to address these concerns. However, since the portal continued to be plagued by technical glitches causing inconvenience to taxpayers, it was decided to hold a meeting between Finance Ministry and Infosys as also other stakeholders on 22.06.2021. -

Sovereign Wealth Funds Ending United States Protectionism?

Sovereign Wealth Funds ending United States protectionism? Explaining the US acceptance of foreign governments’ investments in US financial institutions at the onset of the subprime mortgage crisis Author: Joop Overkamp Student number: S4483774 Degree: Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in political science (MSc) Specialization: International Political Economy Supervisor: Dr. T.R. Eimer Faculty: Nijmegen School of Management University: Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Date of submission: June 24, 2020 Word count: 21.760 1 Abstract For a long time, the United States of America (US) tried to prevent acquisitions of foreign governments into vital economic sectors. This long-held policy seemed to change during the onset of the subprime mortgage crisis When Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) acted as White knight’s and provided much-needed liquidity for failing US financial institutions. The US government did not intervene in these investments, Which caused politicians to publicly voice their concerns and lengthy congressional hearings. The final governmental response Was to accept investments and enact ‘best practices’ for SWFs and ‘guidelines’ for SWF investment recipient countries at the IMF and OECD level. Which respectively ensured that SWFs do not invest politically, and SWF investment recipient countries do not discriminate betWeen state oWned enterprises or private companies. This research tried to understand this policy decision through the detailed analysis of three policy phases. It finds that neither the Neoclassical Mercantilist nor the Critical Political Economy (CPE) approach can fully explain this decision. Interestingly, a combination betWeen both approaches seems to explain Why the US chooses to proliferate neoliberal policies that do not regulate SWFs directly. -

About Mathias Cormann Recent Roles Previous Professional Experience Qualifications

About Mathias Cormann Mathias Cormann was until recently Australia’s longest-serving Finance Minister and Leader of the Government in the Australian Senate. An experienced political leader with strong economic credentials, Mathias has delivered Australia’s annual Federal Budgets since 2013. In this role, he has led complex negotiations with a broad spectrum of political parties. Born in Belgium, Mathias Cormann migrated to Australia in 1996. Mathias would bring a distinctive perspective to the Secretary- General role, having spent half of his life in Europe and half in the Asia-Pacific. His experience gives him rare insights into the cultures, economic strengths and political dynamics of both regions. Mathias is a strong advocate for the positive power of open markets and free trade and the importance of rules based global economic governance. He has represented Australia in the OECD, G20, APEC, ASEAN and the World Economic Forum. In 2018, Mathias was awarded the Grand Cross with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, for his work in advancing German-Australian relations. From August 2018 to May 2019, Mathias served as Minister for the Public Service. In this role, he led initiatives to modernise and reform Australia’s public sector, with a focus on achieving higher levels of transparency, efficiency and good governance. Mathias is married to Hayley and they have two young daughters, Isabelle and Charlotte. R e c e n t r o l e s Minister for Finance - 2013-2020 Leader of the Australian Government in