Edible-Wild-Plants.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R. Okie1 U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, 21 Dunbar Road, Byron, GA 31008 Recent utilization of genetic resources of peach [Prunus persica (‘Quetta’ from India, ‘John Rivers’ from England, and ‘Lippiatts’ (L.) Batsch] and Japanese plum (P. salicina Lindl. and hybrids) has from New Zealand) were critical to the development of modern been limited in the United States compared with that of many crops. nectarines in California (Taylor, 1959). However, most fresh-market Difficulties in collection, importation, and quarantine throughput have peach breeding programs in the United States have used germplasm limited the germplasm available. Prunus is more difficult to preserve developed in the United States for cultivar development (Okie, 1998). because more space is needed than for small fruit crops, and the shorter Only in New Jersey was there extensive hybridization with imported life of trees relative to other tree crops because of disease and insect clones, and most of these hybrids have not resulted in named cultivars problems. Lack of suitable rootstocks has also reduced tree life. The (Blake and Edgerton, 1946). trend toward fewer breeding programs, most of which emphasize In recent years, interest in collecting and utilizing novel germplasm “short-term” (long-term compared to most crops) commercial cultivar has increased. For example, non-melting clingstone peaches from development to meet immediate industry needs, has also contributed Mexico and Brazil have been used in the joint USDA–Univ. of to reduced use of exotic material. Georgia–Univ. of Florida breeding program for the development of Probably all modern commercial peaches grown in the United early ripening, non-melting, fresh-market peaches for low-chill areas States are related to ‘Chinese Cling’, a peach imported from China (Beckman and Sherman, 1996). -

Wild Goose Plum Prunus Hortulana ILLINOIS RANGE Tree in Flower

wild goose plum Prunus hortulana Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division/Phylum: Magnoliophyta Wild goose plum is a small tree that may attain a Class: Magnoliopsida height of 20 feet and a trunk diameter of eight Order: Rosales inches. Its gray or brown bark becomes scaly at maturity. Twigs are slender, red-brown and smooth. Family: Rosaceae The ovoid, red-brown buds are about one-fourth ILLINOIS STATUS inch in length. Leaves are arranged alternately along the stem. These simple, oblong to oval leaves may common, native be as much as six inches long and two inches wide. Each leaf is finely-toothed along the edges. Each tooth has a gland at its tip. The leaf is green and smooth on the upper surface and pale and sometimes hairy on the lower surface. Flowers develop in clusters, up to one inch wide. The five- petaled, white flowers appear after the leaves are partly grown. The fruit is a drupe (a seed enclosed in a hard, dry material that in turn is covered with a fleshy material). The drupe is nearly spherical and up to one inch in diameter. This red, fleshy fruit is hard, bitter and contains one seed. BEHAVIORS © Guy Sternberg Wild goose plum may be found in the southern one- half of Illinois. It grows in wood edges and thickets. tree in flower Flowers are produced from March through April. The wood is hard and brown. ILLINOIS RANGE © Guy Sternberg flowering branches © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

A Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center, Tulsa County, Oklahoma

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 29 Volume 13, December 2013 A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE MARY K. OXLEY NATURE CENTER, TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA Amy K. Buthod Oklahoma Biological Survey Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory Robert Bebb Herbarium University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019-0575 (405) 325-4034 Email: [email protected] Keywords: flora, exotics, inventory ABSTRACT This paper reports the results of an inventory of the vascular flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A total of 342 taxa from 75 families and 237 genera were collected from four main vegetation types. The families Asteraceae and Poaceae were the largest, with 49 and 42 taxa, respectively. Fifty-eight exotic taxa were found, representing 17% of the total flora. Twelve taxa tracked by the Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory were present. INTRODUCTION clayey sediment (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1977). Climate is Subtropical The objective of this study was to Humid, and summers are humid and warm inventory the vascular plants of the Mary K. with a mean July temperature of 27.5° C Oxley Nature Center (ONC) and to prepare (81.5° F). Winters are mild and short with a a list and voucher specimens for Oxley mean January temperature of 1.5° C personnel to use in education and outreach. (34.7° F) (Trewartha 1968). Mean annual Located within the 1,165.0 ha (2878 ac) precipitation is 106.5 cm (41.929 in), with Mohawk Park in northwestern Tulsa most occurring in the spring and fall County (ONC headquarters located at (Oklahoma Climatological Survey 2013). -

(Prunus Spp) Using Random Amplified Microsatellite Polymorphism Markers

Assessment of genetic diversity and relationships among wild and cultivated Tunisian plums (Prunus spp) using random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers H. Ben Tamarzizt, S. Ben Mustapha, G. Baraket, D. Abdallah and A. Salhi-Hannachi Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Immunology & Biotechnology, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia Corresponding author: A. Salhi-Hannachi E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) Received January 8, 2014 Accepted July 8, 2014 Published March 20, 2015 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2015.March.20.4 ABSTRACT. The usefulness of random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers to study the genetic diversity and relationships among cultivars belonging to Prunus salicina and P. domestica and their wild relatives (P. insititia and P. spinosa) was investigated. A total of 226 of 234 bands were polymorphic (96.58%). The 226 random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers were screened using 15 random amplified polymorphic DNA and inter-simple sequence repeat primers combinations for 54 Tunisian plum accessions. The percentage of polymorphic bands (96.58%), the resolving power of primers values (135.70), and the polymorphic information content demonstrated the efficiency of the primers used in this study. The genetic distances between accessions ranged from 0.18 to 0.79 with a mean of 0.24, suggesting a high level of genetic diversity at the intra- and interspecific levels. The unweighted pair group with arithmetic mean dendrogram Genetics and Molecular Research 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br Genetic diversity of Tunisian plums using RAMPO markers 1943 and principal component analysis discriminated cultivars efficiently and illustrated relationships and divergence between spontaneous, locally cultivated, and introduced plum types. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

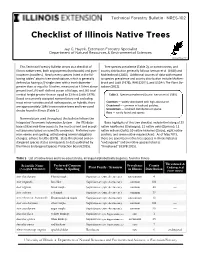

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species Through Southeastern

Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crop Species through Southeastern and Midwestern United States June and July 2007 Glassy Mountain, South Carolina Participants: Kim E. Hummer, Research Leader, Curator, USDA ARS NCGR 33447 Peoria Road, Corvallis, Oregon 97333-2521 phone 541.738.4201 [email protected] Chad E. Finn, Research Geneticist, USDA ARS HCRL, 3420 NW Orchard Ave., Corvallis, Oregon 97330 phone 541.738.4037 [email protected] Michael Dossett Graduate Student, Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture, Corvallis, OR 97330 phone 541.738.4038 [email protected] Plant Collecting Expedition for Berry Crops through the Southeastern and Midwestern United States, June and July 2007 Table of Contents Table of Contents.................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements:................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 4 Part I – Southeastern United States ...................................................................................... 5 Summary.............................................................................................................................. 5 Travelog May-June 2007.................................................................................................... 6 Conclusions for part 1 ..................................................................................................... -

Pharmaceutical Applications of a Pinyon Oleoresin;

PHARMAC E UT I CAL A PPL ICAT IONS OF A PINYON OLEORESIN by VICTOR H. DUKE A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Pharmacognosy College of Pharmacy University of Utah May, 1961 LIBRARY UNIVERSITY elF UTAH I I This Thesis for the Ph. D. degree by Victor H. Duke has been approved by Reader, Supervisory Head, Major Department iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge his gratitude to each of the following: To Dr. L. David Hiner, his Dean, counselor, and friend, who suggested the problem and encouraged its completion. To Dr. Ewart A. Swinyard, critical advisor and respected teacher, for inspiring his original interest in pharmacology. To Dr. Irving B. McNulty and Dr. Robert K. Vickery, true gentlemen of the botanical world, for patiently intro ducing him to its wonders. To Dr. Robert V. Peterson, an amiable faculty con sultant, for his unstinting assistance. To his wife, Shirley and to his children, who have worked with him, worried with him, and who now have succeeded with him. i v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. REPORTED USES OF PINYON OLEORESI N 6 A. Internal Uses 6 B. External Uses 9 III. GENUS PINUS 1 3 A. Introduction 13 B. Pinyon Pines 14 1. Pinus edulis Engelm 18 2. Pinus monophylla Torr. and Frem. 23 3. Anatomy 27 (a) Leaves 27 (b) Bark 27 (c) Wood 30 IV. COLLECTION OF THE OLEORESIN 36 A. Ch ip Method 40 B. -

Are Our Raspberries Derived from American Or European Species ? Geo

ARE OUR RASPBERRIES DERIVED FROM AMERICAN OR EUROPEAN SPECIES ? GEO. M. DARROW Bureau of Plant Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture T HAS been the common supposition Foche* makes but one species of both, of pomologists that most of our classing R. strigosius as a variety of I cultivated red raspberries are de- R. idaeus. His distinctions between the rived from American species. Va- two, however, are similar to those of rieties from the European species have Rydberg, but he emphasizes the fact been considered very susceptible to win- that while the upper part of the ma- ter injury while those from the Amer- ture plants of R. strigosus is densely, ican species have been considered very rarely sparsely bristly, the upper part hardy. Because varieties of red rasp- of R. idaeus is without bristles, berries commonly grown in this conn- An examination of Rubus idaeus try have been moderately hardy they grown in this country under garden were, therefore, thought to be derived conditions show that these distinctions from the American species. are apparently correct. As Rydberg A brief review of the points of dif- states, the plants are not glandular- ference between the two species of red hispid, the stems, peduncles, and raspberries which are the parents of our sepals are tomentose, the fruit is dark cultivated varieties will show how er- red • and thimble shaped. As Card roneous this view is. states, the canes are stouter, and less Rydberg1 gives the following distinc- free in habit of growth. The'prickles tions between the European and Amer- are firm, recurved, and less numerous ican species : than the bristles of R- strigosus. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Idaho's Registry of Champion Big Trees 06.13.2019 Yvonne Barkley, Director Idaho Big Tree Program TEL: (208) 885-7718; Email: [email protected]

Idaho's Registry of Champion Big Trees 06.13.2019 Yvonne Barkley, Director Idaho Big Tree Program TEL: (208) 885-7718; Email: [email protected] The Idaho Big Tree Program is part of a national program to locate, measure, and recognize the largest individual tree of each species in Idaho. The nominator(s) and owner(s) are recognized with a certificate, and the owners are encouraged to help protect the tree. Most states, including Idaho, keep records of state champion trees and forward contenders to the national program. To search the National Registry of Champion Big Trees, go to http://www.americanforests.org/bigtrees/bigtrees- search/ The National Big Tree program defines trees as woody plants that have one erect perennial stem or trunk at least 9½ inches in circumference at DBH, with a definitively formed crown of foliage and at least 13 feet in height. There are more than 870 species and varieties eligible for the National Register of Big Trees. Hybrids, minor varieties, and cultivars are excluded from the National listing but all but cultivars are accepted for the Idaho listing. The currently accepted scientific and common names are from the USDA Plants Database (PLANTS) http://plants.usda.gov/java/ and the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) http://www.itis.gov/ Champion trees status is awarded using a point system. To calculate a tree’s total point value, American Forests uses the following equation: Trunk circumference (inches) + height (feet) + ¼ average crown spread (feet) = total points. The registered champion tree is the one in the nation with the most points. -

Sand Plums for Home and Commercial Production

Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service HLA-6258 Sand Plums for Home and Commercial Production Beth McMahon Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Fact Sheets Research Assistant Oklahoma State University are also available on our website at: http://osufacts.okstate.edu Bruce Dunn Assistant Professor Geyer, 2010). Flowering will last for a couple of weeks and Oklahoma State University either red or yellow fruit will begin to form afterward. Ripening of the fruit occurs from June to early August and are either Sand plums, also known as Chickasaw plum, Cherokee yellow or a bright red. Both colors occur in the same areas plum, or Sandhill plum (Prunus angustifolia Marshall), are native of Oklahoma. Fruit size can range from ¼ inch to 1 inch. It fruit-producing shrubs or small trees in Oklahoma (Figure 1). is recommended that long sleeves be worn while collecting Use of sand plums range from cover for native bird species fruit since the plants may be thorny, depending upon how to making jams, jellies, and wine from the fruit. Commercial damaged they have been by deer and cattle in the past. desire in making jams and jellies has led to a rising interest in cultivating sand plums for home and orchard production. The purpose of this publication is to provide some basic knowledge Selecting Plants on how to identify, propagate, and grow your own sand plums. Besides selecting plants for fruit size and crop load, Sand plums range from 2 feet to 25 feet high, depend- you may also want to consider selecting plants that have ing upon soil and water conditions (Row and Geyer, 2010).