A Rediscussion on Glocalization: Analysis on the Shift From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual-Forward-Focus

Scroll Back The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers Itay Keren Untame [email protected] @itayke Scrolling Big World, Small Screen Scrolling: Neural Background Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Thalamus Relay sensory signals to the cerebral cortex (e.g. vision, motor) Amygdala Emotional reactions of fear and anxiety, memory regulation and conditioning "fight-or-flight" regulation Familiar visual patterns as well as pattern changes may cause anxiety unless regulated Vestibular System Balance, Spatial Orientation Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Natural image stabilizer Conflicting sensory signals (Visual vs. Vestibular) may lead to discomfort and nausea* * much worse in 3D (especially VR), but still effective in 2D Scrolling with Attention, Interaction and Comfort Attention: Use the camera to provide sufficient game info and feedback Interaction: Make background changes predictable, tightly bound to controls Comfort: Ease and contextualize background changes Attention The Elements of Scrolling Interaction Comfort Scrolling Nostalgia Rally-X © 1980 Namco Scramble © 1981 Jump Bug © 1981 Defender © 1981 Konami Hoei/Coreland (Alpha Denshi) Williams Electronics Vanguard -

View List of Games Here

Game List SUPER MARIO BROS MARIO 14 SUPER MARIO BROS3 DR MARIO MARIO BROS TURTLE1 TURTLE FIGHTER CONTRA 24IN1 CONTRA FORCE SUPER CONTRA 7 KAGE JACKAL RUSH N ATTACK ADVENTURE ISLAND ADVENTURE ISLAND2 CHIP DALE1 CHIP DALE3 BUBBLE BOBBLE PART2 SNOW BROS MITSUME GA TOORU NINJA GAIDEN2 DOUBLE DRAGON2 DOUBLE DRAGON3 HOT BLOOD HIGH SCHOOL HOT BLOOD WRESTLE ROBOCOP MORTAL KOMBAT IV SPIDER MAN 10 YARD FIGHT TANK A1990 THE LEGEND OF KAGE ALADDIN3 ANTARCTIC ADVENTURE ARABIAN BALLOON FIGHT BASE BALL BINARY LAND BIRD WEEK BOMBER MAN BOMB SWEEPER BRUSH ROLLER BURGER TIME CHAKN POP CHESS CIRCUS CHARLIE CLU CLU LAND FIELD COMBAT DEFENDER DEVIL WORLD DIG DUG DONKEY KONG DONKEY KONG JR DONKEY KONG3 DONKEY KONG JR MATH DOOR DOOR EXCITEBIKE EXERION F1 RACE FORMATION Z FRONT LINE GALAGA GALAXIAN GOLF RAIDON BUNGELING BAY HYPER OLYMPIC HYPER SPORTS ICE CLIMBER JOUST KARATEKA LODE RUNNER LUNAR BALL MACROSS JEWELRY 4 MAHJONG MAHJONG MAPPY NUTS MILK MILLIPEDE MUSCLE NAITOU9 DAN SHOUGI H NIBBLES NINJA 1 NINJA3 ROAD FIGHTER OTHELLO PAC MAN PINBALL POOYAN POPEYE SKY DESTROYER Space ET STAR FORCE STAR GATE TENNIS URBAN CHAMPION WARPMAN YIE AR KUNG FU ZIPPY RACE WAREHOUSE BOY 1942 ARKANOID ASTRO ROBO SASA B WINGS BADMINGTON BALTRON BOKOSUKA WARS MIGHTY BOMB JACK PORTER CHUBBY CHERUB DESTROYI GIG DUG2 DOUGH BOY DRAGON TOWER OF DRUAGA DUCK ELEVATOR ACTION EXED EXES FLAPPY FRUITDISH GALG GEIMOS GYRODINE HEXA ICE HOCKEY LOT LOT MAGMAX PIKA CHU NINJA 2 QBAKE ONYANKO TOWN PAC LAND PACHI COM PRO WRESTLING PYRAMID ROUTE16 TURBO SEICROSS SLALOM SOCCER SON SON SPARTAN X SPELUNKER -

10-Yard Fight 1942 1943

10-Yard Fight 1942 1943 - The Battle of Midway 2048 (tsone) 3-D WorldRunner 720 Degrees 8 Eyes Abadox - The Deadly Inner War Action 52 (Rev A) (Unl) Addams Family, The - Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt Addams Family, The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - DragonStrike Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Heroes of the Lance Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Hillsfar Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Pool of Radiance Adventure Island Adventure Island II Adventure Island III Adventures in the Magic Kingdom Adventures of Bayou Billy, The Adventures of Dino Riki Adventures of Gilligan's Island, The Adventures of Lolo Adventures of Lolo 2 Adventures of Lolo 3 Adventures of Rad Gravity, The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer After Burner (Unl) Air Fortress Airwolf Al Unser Jr. Turbo Racing Aladdin (Europe) Alfred Chicken Alien 3 Alien Syndrome (Unl) All-Pro Basketball Alpha Mission Amagon American Gladiators Anticipation Arch Rivals - A Basketbrawl! Archon Arkanoid Arkista's Ring Asterix (Europe) (En,Fr,De,Es,It) Astyanax Athena Athletic World Attack of the Killer Tomatoes Baby Boomer (Unl) Back to the Future Back to the Future Part II & III Bad Dudes Bad News Baseball Bad Street Brawler Balloon Fight Bandai Golf - Challenge Pebble Beach Bandit Kings of Ancient China Barbie (Rev A) Bard's Tale, The Barker Bill's Trick Shooting Baseball Baseball Simulator 1.000 Baseball Stars Baseball Stars II Bases Loaded (Rev B) Bases Loaded 3 Bases Loaded 4 Bases Loaded II - Second Season Batman - Return of the Joker Batman - The Video Game -

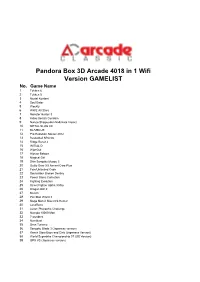

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

The Birth of “Final Fantasy”: Square Corporation

岡山大学経済学会雑誌37(1),2005,63~88 The Birth of “Final Fantasy”: Square Corporation Daiji Fujii 1. Introduction “Final Fantasy” was one of the million selling series of role playing games (RPGs). Square Corporation, which might be known as Square Soft outside Japan, had been known as the Japanese software developer to release this series approximately every year. Square enjoyed large annual turnovers from the series and diversified their businesses including a CG movie production. Journalism shed a spotlight on this software factory as a member of the “Winners Club” in Japan’s economy under the futureless recession in the 1990s. This heroic entrepreneurial company and its biggest rival, Enix Corporation Limited, known to be the publisher of “Dragon Quest” series (“Dragon Warrior” in North America), the other one of the twin peaks of Japanese RPG titles, announced to become one in November, 2002. The news became a national controversy, because the home video game was expected to be the last remedy to Japan’s trade imbalance of software industry. According to the report published by Japan’s industry consortium, Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association (CESA), the top 30 titles in terms of the total shipment between 1983−2002 included 13 RPG titles released by both Square and Enix, second to Nintendo’s 14 titles of various genres (See table 1). Independent software firms had had powerful impacts upon Nintendo, which had the combination of Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) as a dominant platform and “Mario” as a killer content. In 1996, Nintendo’s hegemony in the platform market was rooted out by the re−alliances amongst software suppliers and almost dying PlayStation of Sony Computer Entertainment (SCE). -

L'evoluzione Della Relazione Uroborica Fra Videogioco E Musica: Il Singolare Caso Di Transculturalità Dell'industria Videoludica Giapponese

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle Attività culturali Dipartimento di Filosofia e Beni culturali Tesi di Laurea L'evoluzione della relazione uroborica fra videogioco e musica: il singolare caso di transculturalità dell'industria videoludica giapponese Relatore: Giovanni De Zorzi Correlatrice: Maria Roberta Novielli Laureando: Enrico Pittalis Numero di Matricola: 871795 Anno accademico 2018/2019 Sessione Straordinaria Ringrazio Valentina, la persona più preziosa, senza cui questo lavoro non sarebbe stato possibile. Ringrazio i miei relatori, i professori Giovanni De Zorzi e Maria Roberta Novielli, che mi hanno guidato lungo questo percorso con grande serietà. Ringrazio i miei amici per i tanti consigli, confronti e spunti di riflessione che mi hanno dato. Ringrazio il Dott. Tommaso Barbetta per avermi incoraggiato ed aiutato a trovare gli obiettivi e il Prof. Toshio Miyake per avermi suggerito dei materiali di approfondimento. Ringrazio il Prof. Marco Fedalto per avermi dato importantissimi consigli. Ringrazio i miei genitori per avermi sostenuto nelle mie scelte, anche le più stravaganti. Glossario: - Anime: termine con cui si fa riferimento alle serie televisive animate prodotte in Giappone, spesso adattamenti televisivi di romanzi brevi o manga, talvolta videogiochi. - Arcade: prestito linguistico dall’inglese, termine con cui ci si riferisce alle “Macchine da gioco”, costituita fisicamente da un videogioco posto all'interno di un cabinato di grandi dimensioni operabile a monete o gettoni, che normalmente viene posto in postazioni pubbliche come sale giochi, bar, talvolta cinema e centri commerciali. L’Etimologia è incerta, probabilmente derivante da “Arcata” facente riferimento storicamente a lunghi viali sotto i portici dei borghi, dove si trovavano le botteghe e luoghi dediti al divertimento. -

Gocomma Games List

Game List as displayed on the Gocomma Handheld Games Console, some of these may be misspelt, I haven’t the time to confirm the huge list, so I’ve written them down as they’re displayed. ❖ Super Mario Bros ❖ Mario 14 ❖ Super Mario Bros 3 ❖ Dr Mario ❖ Mario Bros ❖ Turtle 1 ❖ Turtle Fighter ❖ Contra 24 in 1 ❖ Contra Force ❖ Super Contra 7 ❖ Kage ❖ Jackal ❖ Rush n Attack ❖ Adventure Island ❖ Adventure Island 2 ❖ Chip Dale 1 ❖ Chip Dale 3 ❖ Bubble Bobble Par ❖ Snow Bros ❖ Mitsume Ga Tooru ❖ Ninja Gaiden 2 ❖ Double Dragon 2 ❖ Double Dragon 3 ❖ Hot Blood High Sc ❖ Hot Blood Wrestle ❖ Robocop ❖ Mortal Kombat IV ❖ Spider Man ❖ 10 Yard Fight ❖ Tank A1990 ❖ The Legend of Kag ❖ Aladdin 3 ❖ Antarctic Adventure ❖ Arabian ❖ Balloon Fight ❖ Base Ball ❖ Binary Land ❖ Bird Week ❖ Bomber Man ❖ Bomb Sweeper ❖ Brush Roller ❖ Burger Time ❖ Chakn Pop ❖ Chess ❖ Circus Charlie ❖ Clu Clu Land ❖ Field Combat ❖ Defender ❖ Devil World ❖ Dig Dug ❖ Donkey Kong ❖ Donkey Kong Jr ❖ Donkey Kong 3 ❖ Donkey Kong Jr Ma ❖ Door Door ❖ Excitebike ❖ Exerion ❖ F1 Race ❖ Formation Z ❖ Front Line ❖ Galaga ❖ Galaxian ❖ Golf ❖ Raidon Bungeling ❖ Hyper Olympic ❖ Hyper Sports ❖ Ice Climber ❖ Joust ❖ Karateka ❖ Lode Runner ❖ Lunar Ball ❖ Macross ❖ Jewelry ❖ 4 Mahjong ❖ Mahjong ❖ Mappy ❖ Nuts Milk ❖ Millipede ❖ Muscle ❖ Naitou9 Dan Shoug ❖ Nibbles ❖ Ninja 1 ❖ Ninja 3 ❖ Road Fighter ❖ Othello ❖ Pac Man ❖ Pinball ❖ Pooyan ❖ Popeye ❖ Sky Destroyer ❖ Space Et ❖ Star Force ❖ Star Gate ❖ Tennis ❖ Urban Champion ❖ Warpman ❖ Yie Ar Kung Fu ❖ Zippy Race ❖ Warehouse Boy ❖ 1942 ❖ Arkanoid ❖ Astro -

2600 in 1 Game List

2600 in 1 Game List www.myarcade.com.au # Name 50 Agu's Adventure 1 005 51 Air Attack (set 1) 2 10-Yard Fight 52 Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit (World) 3 12Yards 53 Air Combat 4 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 54 Air Command 5 1942 (Revision A) 55 Air Duel (Japan) 6 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 56 Air Gallet (Europe) 7 1943: The Battle of Midway (US, Rev C) 57 Air Strike 8 1943:The Battle of Midway 58 Airwolf 9 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 59 Ajax 10 1945k III 60 Akkanbeder 11 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 61 Aladdin Fairy Tale 12 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 62 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 13 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043) 63 Alibaba and 40 Thieves (NGH043) 64 Alien Arena 14 4 En Raya (set 1) 65 Alien Challenge (World) 15 4 Fun in 1 66 Alien Sector 16 4-D Warriors (315-5162) 67 Alien Storm (World, 2 Players, FD1094 317- 17 5-Person Volleyball 0154) 18 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 68 Alien Syndrome (set 4, System 16B, 19 8 Billiards unprotected) 20 800 Fathoms 69 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520) 21 '88 Games 70 Aliens (World set 1) 22 8Th Heat Output 71 All American Football 23 9 Ball Shootout 72 Alligator Hunt 24 99:The Last War 73 Alpha Mission 25 9Th Forward 2 74 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian (NGM- 26 A Beautiful New World 007)(NGH-007) 27 A Drop Of Dawn Water 75 Alpha One 28 A Drop Of Dawn Water 2 76 Alpine Ski (set 1) 29 A Hero Like Me 77 Alsen 30 A Sword 78 Altered Beast (set 8, 8751 317-0078) 31 A.D.2083 79 Amazing World 32 Abscam 80 American Speedway -

Gx-888155 WIERLEES

Gx-888155 WIERLEES 1 CONTRA 1 156 POLICE VS THIEF 311 2 CONTRA FORC 157 PONG PONG 312 3 CONTRA 7 158 POWER ROBOT 313 4 KAGE 159 PULVERATION 314 5 SUPER MARIO 160 RABBIT VILLAGE 315 6 MARIO 3 161 RIVER JUMP 316 7 MARIO 6 162 (POPAYE) 317 8 DR MARIO 163 (RYGAR) 318 9 MARIO BROS 164 SPACE BASE 319 10 TURTLES 1 165 SPIDERMAN 2 320 11 TURTLES 4 166 SPIDERMAN 1 321 12 DOUBLE DRAGON 167 SPRING WORLD 322 13 DOUBLE DRAGON 2 168 (CAPTAIN AMERICA) 323 14 MEGA MAN 3 169 SUBMARINE 324 15 BLOOD WRESTLE 170 THROUGHMAN 325 16 BLOOD SOCCER2 171 TOY FACTORY 326 17 ADVEN ISLAND 172 UTMOST WARFARE 327 18 ADVEN ISLAND 2 173 VIGILANT 328 19 CHIP DALE 1 174 WARZONE (CASTLEVANIA) 329 20 CHIP DALE 3 175 WATER PIPE 330 21 BUBBLE BOBBLE 2 176 WILDWORM 331 22 SNOW BROS 177 WONDER BALL 332 23 MITSUME 178 CLIMBING 333 24 NINJA GAIDEN 2 179 (THE LITTLE MERMAID) 334 25 SILK WORM 180 (SUPER HANG ON) 335 26 ANGRY BIRD 181 90 TANK 336 27 (SHOW BROTHERS) 182 ARABIAN 337 28 ALADDIN 3 183 BALLOON FIGHT 338 29 ARKISTAS RING 184 BASE BALL 339 30 (STREET FIGHTER) 185 BINARY LAND 340 31 (ADVENTURE ISLAND -1 2 3)186 BIRD WEEK (POOYANS) 341 32 (THE ADVENTURE OF BATMAN)187 BOMBER MAN 342 33 FLIPULL 188 BOMB SWEEPER 343 34 GHOST BUSTERS 189 BRUSH ROLLER 344 35 GRADIUS 190 BURGER TIME 345 36 (GUIRELLA WAR) 191 CHACK N POP 346 37 KING KNIGHT 192 (BALLON FIGHT) 347 38 MICKEY MOUSE 193 CIRCUS CHARLIE 348 39 (BAT MAN RETURN OF THE JOKER)194 CLU LCU LAND 349 40 (BATTLE CITY) 195 COMBAT 350 41 POWER SOCCER 196 (TURTLES TOURANAMENT FIGHT 351 42 (TINY TOON ALL PARTS) 197 DEVIL WORLD 352 43 -

Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia Steven Cuff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2017 Now You're Playing with Power: Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia Steven Cuff University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Cuff, Steven, "Now You're Playing with Power: Nintendo and the Commodification of Nostalgia" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1459. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1459 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOW YOU’RE PLAYING POWER: NINTENTO AND THE COMMODIFICATION OF NOSTALGIA by Steve Cuff A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT NOW YOU’RE PLAYING WITH POWER: NINTENDO AND THE COMMODIFICATION OF NOSTALGIA by Steve Cuff The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Z. Newman This thesis explores Nintendo’s past and present games and marketing, linking them to the broader trend of the commodification of nostalgia. The use of nostalgia by Nintendo is a key component of the company’s brand, fueling fandom and a compulsive drive to recapture the past. By making a significant investment in cultivating a generation of loyal fans, Nintendo positioned themselves to later capitalize on consumer nostalgia. -

International Conference on Japan Game Studies 2013

International Conference on Japan Game Studies 2013 Conference Abstracts May 24-26, 2013 @ Soshikan Hall, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan Organizer i ii International Conference on Japan Game Studies 2013 Dates: May 24-26, 2013 Kinugasa Campus, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan Main Organizer: Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies, Ritsumeikan University Co-organizers: Prince Takamado Japan Centre, University of Alberta Canadian Institute for Research Computing in the Arts, University of Alberta GRAND Network of Centres of Excellence Conference Co-Chairs: Mitsuyuki Inaba, College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University Kaori Kabata, Prince Takamado Japan Centre, University of Alberta Program Committee: Kazufumi Fukuda, Graduate School of Core Ethics and Frontier Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Koichi Hosoi, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Masaharu Miyawaki, College of Law, Ritsumeikan University Akinori Nakamura, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Geoffrey Rockwell, Canadian Institute for Research Computing in the Arts, University of Alberta Masayuki Uemura, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Shuji Watanabe, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Hiroshi Yoshida, Graduate School of Core Ethics and Frontier Sciences, Ritsumeikan University Cover design: Kazufumi Fukuda, Ritsumeikan University Editorial & Layout: Barbara Carter, University of Alberta 1 TableTable ofof ContentsContents ConferenceInformation -

Americans Garners Cheated

THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY FOCUS October 17, 2000 PAGE 19 Gaming Console.s.of the Past, Present and Future from CONSOLES, page 16 opposed to Atari' s 16 colors. Better yet, the in 1982, which p4cked the power of the game quality was controlled. Nintendo pro . Atari 400/800 computer systems, but grammed the NES only to play authorized offered the same, tired game titles. This cartridges and sold liscenses to software system didn't catch on because one of its developers. Nintendo then produced the rival company, Coleco, was releasing the games themselves, allowing for a little most popular game in the arcades, Donkey quality control. Many people bought the Kong. Coleco also had an Atari 2600 com NES just to play the pack-in game Super patible interface before Atari itself did for Mario Brothers. Other excellent games for the 5200.The year also saw Milton . the NES are Castlevania and The Legend of Bradley's Microvision, and Intellivision II Zelda series. and Intellivoice. This was indeed a boom Sega, after three years of struggling to ing year for the home video game market compete with the NES, decid~d to go with with Mattei's Aquarius and Coleco's the 16-bit technology and released the Sega Gemenii also released for sales. Genesis in 1989. Sega also knew the Atari planned to strike back with the importance of game quality and third party Atari 7800 ProSystem, which featured an control from the industry crash in '84 and all-new graphics chip, a better color pallat recruited 30 outside developers within one te and a computer keyboard add-on that year of the system's release to write games.