Movement Patterns of Great, Intermediate and Little Egrets from Australian Breeding Colonies. Corella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds of Gag Island, Western Papuan Islands, Indonesia

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.23(2).2006.115-132 [<ecords o{ the rVcstCrJJ Australian Museum 23: 115~ n2 (2006). The birds of Gag Island, Western Papuan islands, Indonesia R.E. Johnstone Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welsh pool DC Western Australia 6'1S6 Abstract This report is based mainly on data gathered during a biological survey of C;ag Island by a joint Western Australian Museum, Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense and Herbarium Bogoriense expedition in July 1'197. A total of 70 species of bird have been recorded for Gag Island and a number of these represent new island and/or Raja Ampat Archipelago records. Relative abundance, status, local distribution and habitat preferences found for each species arc described, extralimital range is outlined and notes on taxonomv are also given. No endemic birds were recorded for Gag Island but a number of species show significant morphological variation from other island forms and may prove to be distinct taxonomically. INTRODUCTION undergo geographic variation for taxonon,ic, Gag Island (0025'S, 129 U 53'E) is one of the Western morphological and genetic studies. The Papuan or Raja Ampat Islands, lying just off the annotated checklist provided covers every Vogelkop of Irian Jaya, between New Guinea and species recorded, both historically and during Halmahera, Indonesia. These islands include (from this survey. north to south) Sayang, Kawe, Waigeo, Gebe, Gag, In the annotated list I summarise for each species Gam, Batanta, Salawati, Kofiau, Misool and a its relative abundance (whether it is very common, number of small islands (Figure 1). Gag Island is common, moderately common, uncommon, scarce separated from its nearest neighbours Gebe Island or rare), whether it feeds alone or in groups, status to the north~west, and Batangpele Island to the (a judgement on whether it is a vagrant, visitor or north-east, by about 40 km of relatively deep sea. -

Criteria 3 Annexure 3.5.1 Department of Collegiate and Technical Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal

Criteria 3 Annexure 3.5.1 Department of Collegiate and Technical Education Sri Mahadeshwara Government First Grade College Kollegal Collaborative Field work with Department of Zoology University of Mysore on survey of aquatic birds has been conducted during the year February 2016 -18 to give Awareness about the. 1. Methods used for survey of birds, 2. Equipment to carry while going for survey. 3. Habit and habitat of birds. 4. Develop the skill of using DSLR camera. Name of the collaborating agency with Name of the participants contact details Dr Sathish S V and Basavarajappa S, Professor of Zoology, students of B Sc. VI Semester University of Mysore. Manasagangothri, 1. Anil kumar B, Mysore. Mob.9449203241 2. Parashivamurthy, 3. Nithin B, 4. Roshan M R. Results obtained: Sl.No Birds observed Order Total mean Relative abundance 1 Common shelduck Anseriformes 0.16 0.02% 2 Cotton pygmy goose Anseriformes 1.77 0.31% 3 Ferruginous duck Anseriformes 1.33 0.23% 4 Garganey Anseriformes 2.5 0.44% 5 Greylag goose Anseriformes 1.27 0.22% 6 Lesser whistling duck Anseriformes 21.61 3.88% 7 Spot billed duck Anseriformes 36.77 6.60% 8 White winged duck Anseriformes 0.83 0.14% 9 Black tailed godwit Charadriiformes 140.72 25.27% 10 Black winged stilt Charadriiformes 35.55 6.38% 11 Bronze winged jacana Charadriiformes 5.61 1.00% 12 Common redshank Charadriiformes 3.11 0.55% 13 Golden plover Charadriiformes 1.38 0.24% 14 Green sandpiper Charadriiformes 9.16 1.64% 15 Marsh Sand piper Charadriiformes 15.72 2.82% 16 Red wattle lapwing Charadriiformes 11.33 -

Courtship and Pair Formation in the Great Egret

COURTSHIP AND PAIR FORMATION IN THE GREAT EGRET Joca• H. Wt•s• THv. reproductivebehavior of the Ardeidaehas receivedconsiderable attention (Verwey 1930; Meanley 1955; Cottrille and Cottrille 1958; Meyerriecks1960 and in Palmer 1962; Baerendsand Van Der Cingel 1962; Blaker 1969a, 1969b; Lancaster 1970). Although Meyerriecks (in Palmer 1962) summarizedthe behavior and McCrimmon (1974) described two sexual displays in detail, the reproductive behavior of the Great Egret (Casmerodiusalbus egretta) remainsessentially unknown. This paper describescourtship and pair formationin this little studied species. STLTD¾AREAS AND METIIODS Most of the observations were made at Avery Island, Iberia Parish, Louisiana, 91ø 30' W, 29ø 30• N. Great Egrets nested on five bamboo platforms (ranging from 4 by 20 m to 7 by 35 m, approximate]y) 2 m above the water surface in "Bird City," a 5-ha freshwater pond in the center of the island. Short lengths of bamboo twigs were provided for nest material. The five bamboo platforms supported 430 •-• 15 nesting pairs of Great Egrets in 1974. This number represented a drastic decline from previous years (E. M. Simmons, pets. comm.) and coincidedwith the establishmentof a second heronry 1 km southeast of Bird City. Additional observationswere made at Headquarter Pond, St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, and Smith Island, Wakulla County, Florida, 84ø 10' W, and 84ø 19• W, 30ø 05' N, and 30ø 03' N, respectively. At Headquarter Pond Great Egrets nested in willows growing in open water more than 0.6 m in depth. The number of nesting egretsdecreased from 38 pairs in 1971 to 9 pairs in 1972 (see below). -

Summary on the Importance of Sumatra's East Coast For

MAP 1 SURVEY AREAS ON THE IMPORTANCE OF SUMATRA'S EAST COAST FOR WATERBIRDS, 104° E with notes on the Asian Dowitcher Limnodromus semipa1matus. c; l e N By Marcel J. Silvius .,IJ\)0 ~ (First draft received 29 October 1987) ••• "'CJ SUMMARY G·"' % ~ Since 1984, three surveys were conducted along the east coast of Sumatra. Several coastal wetlands appeared to be of international importance for waterbirds (according to the criteria of the Ramsar Convention). More than 10,000 large waterbirds were identified, including large numbers { of Milky Storks Mycteria cinerea and Lesser Adjutants Tanjung Datuk Leptopti1os javanicus,, and over 100,000 migratory waders (28 species) were counted. The observation of a minimum total of 3,800 Asian Dowitchers Limnodromus semipa1matus indicates that the east coast of Sumatra is the main wintering area of the species. In areas of high 0 { conservation importance, data were collected on habitat and threats. Several of these areas face heavy reclamation pressure, which necessitates urgent conservation action. INTRODUCTION Prior to 1983 the coastal wetlands of eastern Sumatra had 10 received little ornithological attention, as is the case with most of Indonesia's coastal wetlands. Their importance to migrant and resident waterbirds remained undetermined as is illustrated by the most recent large JAMB I scale marine areas inventory (Salm and Halim, 1984), which lists no waterbird sites of importance on the east coast of Sumatra. Reserve It is only since 1983 that detailed information on the distribution of coastal waterbirds has become available. In that year large numbers of waders were recorded on the mudflats of the Berbak Game Reserve (Silvius, et.a7. -

The Waterbirds and Coastal Seabirds of Timor-Leste: New Site Records Clarifying Residence Status, Distribution and Taxonomy

FORKTAIL 27 (2011): 63–72 The waterbirds and coastal seabirds of Timor-Leste: new site records clarifying residence status, distribution and taxonomy COLIN R. TRAINOR The status of waterbirds and coastal seabirds in Timor-Leste is refined based on surveys during 2005–2010. A total of 2,036 records of 82 waterbird and coastal seabirds were collected during 272 visits to 57 Timor-Leste sites, and in addition a small number of significant records from Indonesian West Timor, many by colleagues, are included. More than 200 new species by Timor-Leste site records were collected. Key results were the addition of three waterbirds to the Timor Island list (Red-legged Crake Rallina fasciata, vagrant Masked Lapwing Vanellus miles and recent colonist and Near Threatened Javan Plover Charadrius javanicus) and the first records in Timor-Leste for three irregular visitors: Australian White Ibis Threskiornis molucca, Ruff Philomachus pugnax and Near Threatened Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata. Records of two subspecies of Gull-billed Tern Gelochelidon nilotica, including the first confirmed records outside Australia of G. n. macrotarsa, were also of note. INTRODUCTION number of field projects in Timor-Leste, including an Important Bird Areas programme and a doctoral study (Trainor et al. 2007a, Timor Island lies at the interface of continental South-East Asia and Trainor 2010). The residence status and nomenclature for some Australia and consequently its resident waterbird and coastal seabird species listed in a fieldguide (Trainor et al. 2007b) and recent review avifauna is biogeographically mixed. Some of the most notable (Trainor et al. 2008) are clarified. Three new island records are findings of a Timor-Leste field survey during 2002–2004 were the documented and substantial new ecological data on distribution discovery of resident breeding populations of the essentially Australian and habitat use are included. -

Bottor of $L|Uoi^Opt)P in WILDLIFE SCIENCE

ECOLOGY AND BIOLOGY OF EGRETS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO Egretta alba, E. intermedia, E. garzetta AND Bubulcus ibis IN AND AROUND ALIGARH ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of $l|Uoi^opt)p IN WILDLIFE SCIENCE BY FAIZA ABBASI DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE SCIENCES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2004 .^ ^'i^ itii;- INTRODUCTION There are 60 species of Ardeids comprising of herons, bitterns and egrets, which occur in most parts of the world. The name Egret comes from the French 'aigrette' meaning the plume feathers of the six species of white Egrets acquired during the breeding season. Egrets are large showy birds readily seen in most neighbourhoods and well appreciated by humans. They often nest on houses and in city parks and feed in pastures, meadows, flooded plains and along drains in towns. They also serve important ecosystem functions such as accelerating nutrient cycling at feeding grounds and regulating fish population. Although a general assumption is such that egrets are not in danger of extinction, baseline data for future conservation is essential as the lack of ftmdamental knowledge makes it difficult to pronounce upon ecological and economic status of most avian species (Hartley, P.H.T., 1948. Ibis 90:361-362). In the west detailed studies are available to serve the purpose but parallel data in India is scanty. This study was undertaken to explore the ecology and biology of four sympatric species of egrets largely focusing on aspects of niche overlap, resource partitioning measures and mechanisms of ecological isolation adapted by the species to maintain coexistence. -

INTERMEDIATE EGRET (Egretta Intermedia) in the ALEUTIAN

NOTES INTERMEDIATE EGRET (EGRETTA INTERMEDIA) IN THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA STEPHAN LORENZ, Department of Biology, University of Texas at Tyler, 3900 University Blvd., Tyler, Texas 75799; [email protected] DANIEL D. GIBSON, University of Alaska Museum, 907 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775; [email protected] The western Aleutian Islands, Alaska, are well known for the occurrence of migrant birds from Asia (Gibson and Byrd 2007). In addition to many Asiatic waterfowl, shorebirds, and passerines, no fewer than six taxa of Asiatic herons have occurred there. Of these herons, the Yellow Bittern (Ixobrychus sinensis), Chinese Egret (Egretta eulophotes), Little Egret (Egretta g. garzetta), and Asiatic subspecies of the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis coromandus) are known from a single record each, while the Indo-Pacific subspecies of the Great Egret (Ardea alba modesta) and Old World subspecies of the Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax n. nycticorax) are both known from multiple occurrences (Gibson and Byrd 2007). To this impressive list can now be added the Intermediate Egret (Egretta i. intermedia). Since the 1970s field biologists have studied nesting seabirds (Procellariidae, Hy- drobatidae, Phalacrocoracidae, Laridae, Alcidae) at Buldir Island (see Byrd and Day 1986), the easternmost of the western Aleutians (at 52° 21' N, 175° 56' E) and the most isolated island in the Aleutian archipelago. During the first weeks following the arrival of the summer 2006 field party, Lorenz and other biologists discovered the carcasses of a total of seven herons—on 25 May an adult Great Egret and an adult Black-crowned Night-Heron, on 28 May a second adult Great Egret, on 30 May an adult Intermediate Egret, and on 7 June three more adult Black-crowned Night-Her- ons. -

Intermediate Egret Egretta Intermedia: First Record for Qatar NEIL G MORRIS

Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia: first record for Qatar NEIL G MORRIS Whilst counting herons and cormorants at Abu Nahkla, Qatar’s premier grey water lagoons, on 22 January 2014, I noticed a white heron (Plates 1–4) being mobbed by two Grey Herons Ardea cinerea. The white heron was trying to join the Grey Herons in a particularly productive feeding area at the edge of the reedbed. The white heron would try to land and then be chased off by the Greys. It was immediately apparent that the white heron was significantly shorter in stature and less bulky than the Greys, and sported a relatively short orange bill. My first thought was Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia, though this was not on the Qatar List. I spent a few minutes taking photographs and comparing the size and structure of the bird with its sparring partners. Along with the bill, I noted long black legs and feet, and an obvious long kinked neck, hence quickly ruling out Little Plates 1–2. Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia at Abu Nahkla, Qatar, 22 January 2014. © Neil G Morris Sandgrouse 36 (2014) 195 Sandgrouse36-2-140716.indd 195 7/17/14 11:31 AM Plates 3–4. Intermediate Egret Egretta intermedia at Abu Nahkla, Qatar, 22 January 2014. © Neil G Morris E. garzetta, Indian Reef E. gularis and Cattle Egrets Bubulcus ibis. The jizz, especially the head and bill shape, also seemed to rule out a runt Western Great Egret Egretta alba. I also discounted an early juvenile heron/egret, given the clean white plumage, uniform bill colouration and also leg colour. -

Amphibian and Reptilian Inventories Augmented by Sampling at Heronries

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS IRCF REPTILES • VOL15, &NO AMPHIBIANS 4 • DEC 2008 189 • 23(1):68–73 • APR 2016 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS METHODS FEATURE ARTICLES . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: AmphibianOn the Road to Understanding the Ecologyand and Conservation Reptilian of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent Inventories ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 AugmentedRESEARCH ARTICLES by Sampling at Heronries . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 1 2 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in FloridaRaju Vyas and B. M. Parasharya 1Krishnadeep ............................................. Tower, MissionBrian Road,J. Camposano, Fatehgunj, Kenneth Vadodara L. Krysko, Kevin300 002,M. Enge, Gujarat, Ellen M. India Donlan, ([email protected]) and Michael Granatosky 212 2Agricultural Ornithology, Anand Agricultural University, Anand 388 110, Gujarat, India ([email protected]) CONSERVATION ALERT . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................ -

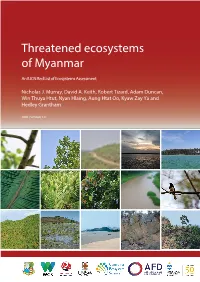

Threatened Ecosystems of Myanmar

Threatened ecosystems of Myanmar An IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Assessment Nicholas J. Murray, David A. Keith, Robert Tizard, Adam Duncan, Win Thuya Htut, Nyan Hlaing, Aung Htat Oo, Kyaw Zay Ya and Hedley Grantham 2020 | Version 1.0 Threatened Ecosystems of Myanmar. An IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Assessment. Version 1.0. Murray, N.J., Keith, D.A., Tizard, R., Duncan, A., Htut, W.T., Hlaing, N., Oo, A.H., Ya, K.Z., Grantham, H. License This document is an open access publication licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Authors: Nicholas J. Murray University of New South Wales and James Cook University, Australia David A. Keith University of New South Wales, Australia Robert Tizard Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar Adam Duncan Wildlife Conservation Society, Canada Nyan Hlaing Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar Win Thuya Htut Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar Aung Htat Oo Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar Kyaw Zay Ya Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar Hedley Grantham Wildlife Conservation Society, Australia Citation: Murray, N.J., Keith, D.A., Tizard, R., Duncan, A., Htut, W.T., Hlaing, N., Oo, A.H., Ya, K.Z., Grantham, H. (2020) Threatened Ecosystems of Myanmar. An IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Assessment. Version 1.0. Wildlife Conservation Society. ISBN: 978-0-9903852-5-7 DOI 10.19121/2019.Report.37457 ISBN 978-0-9903852-5-7 Cover photos: © Nicholas J. Murray, Hedley Grantham, Robert Tizard Numerous experts from around the world participated in the development of the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems of Myanmar. The complete list of contributors is located in Appendix 1. -

Cattle Egret Bubulcus Ibis Habitat Use and Association with Cattle

174 SHORT NOTES Forktail 21 (2005) REFERENCES Mauro, I. (2001) Cinnabar Hawk Owl Ninox ios at Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, in December 1998. Lee, R. J. and Riley, J. (2001) Morphology, plumage, and habitat of Forktail 17: 118–119. the newly described Cinnabar Hawk-Owl from North Sulawesi, Rasmussen, P. C. (1999) A new species of hawk-owl Ninox from Indonesia. Wilson Bull. 113(1): 17–22. North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Wilson Bull. 111(4): 457–464. Ben King, Ornithology Dept., American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, NY10024, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis habitat use and association with cattle K. SEEDIKKOYA, P. A. AZEEZ and E. A. A. SHUKKUR Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis has a worldwide distribution. made five counts per day from 06h00 to 18h00. Egrets In India it is common in a variety of habitats, especially were defined as associated with cattle if they were wetlands, throughout the peninsula. Freshwater found <1 m from an animal and were alert to its marshes and paddy fields were identified as the most movements. We carried out focal observations on important foraging habitats by Meyerricks (1962) and randomly selected foraging egrets, during which we Seedikkoya (2004), although there are pronounced recorded number of strikes, successful captures seasonal variations in the usage of these habitats. Cattle (identified by the characteristic head-jerk swallowing Egrets are often found associated with cattle and behaviour: Heatwole 1965, Dinsmore 1973, Grubb occasionally with pigs, goats, and horses, and also with 1976, Scott 1984) and number of steps in a two- moving vehicles such as tractors. -

Philippines 2013: Visayan Islands & Mindoro Extension

Field Guides Tour Report Philippines 2013: Visayan Islands & Mindoro extension Mar 24, 2013 to Mar 31, 2013 Dave Stejskal & Mark Villa For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Because of a change in the airline schedule to Mindoro, we had to alter our plans for this extension and the main tour, flip-flopping our visit to Mindoro with our first venue on the main tour, Subic Bay. This worked out well since all of you were signed up to do the extension anyway, so nothing was lost. We were pretty fortunate with the weather again on this extension, only having some ill-timed showers on Bohol that kept us off of the trails for a bit of time one afternoon. Other than that, it was lovely! This short extension visited four islands, each with a number of island endemics and/or some Philippine endemics that we never caught up with on the main tour. Mindoro produced Mindoro Racquet-tail, Mindoro Hornbill, Mindoro Bulbul, Scarlet-collared Flowerpecker, "Mindoro" Hawk-Owl, and our surprise Green-faced Parrotfinches; productive Bohol yielded Samar Hornbill, Yellow-breasted Tailorbird, Visayan Blue-Fantail, Black-crowned Babbler, and a lovely Northern Silvery-Kingfisher - plus all of those fabulous Philippine Colugos!; nearly denuded Cebu gave us the newly described Cebu Hawk-Owl, White-vented Whistler, Black Shama, Streak-breasted Bulbul, and our fist Lemon-throated Warbler; and Negros, at the end of the trip, held Visayan Fantail, Visayan Bulbul, Visayan Though tarsiers are found only in SE Asia, they are most closely related to the New World monkeys.