China's Artificial Intelligence Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: the Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril

Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril Michael Matheny, Sonoo Thadaney Israni, Mahnoor Ahmed, and Danielle Whicher, Editors WASHINGTON, DC NAM.EDU PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE • 500 Fifth Street, NW • WASHINGTON, DC 20001 NOTICE: This publication has undergone peer review according to procedures established by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM). Publication by the NAM worthy of public attention, but does not constitute endorsement of conclusions and recommendationssignifies that it is the by productthe NAM. of The a carefully views presented considered in processthis publication and is a contributionare those of individual contributors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the authors’ organizations; the NAM; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data to Come Copyright 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Suggested citation: Matheny, M., S. Thadaney Israni, M. Ahmed, and D. Whicher, Editors. 2019. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril. NAM Special Publication. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs “Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.” --GOETHE PREPUBLICATION COPY - Uncorrected Proofs ABOUT THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE The National Academy of Medicine is one of three Academies constituting the Nation- al Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The Na- tional Academies provide independent, objective analysis and advice to the nation and conduct other activities to solve complex problems and inform public policy decisions. -

Corporate Social Responsibility Roport 2016

This report uses environmentally friendly paper Add:China. Beijing xicheng district revival gate street No.2 P.C.: 100031 Tel.: 010-58560666 China Minsheng Banking Corp., Ltd. Fax: 010-58560690 http: //www.cmbc.com.cn TABLE OF Part II: Build a Sustainable Bank and a Time-Honored Enterprise CONTENTS 02 Message from the Chairman Targeted Poverty Alleviation: Creating Happy Life 04 Message from the President Insisting on the Mission and Promoting Poverty Alleviation 39 Conducting Financial Poverty Alleviation and Highlighting Financial 41 Power of Minsheng Bank Minsheng Moments Carrying out targeted Poverty Alleviation and Adhering to 45 38 Sustainable Development Path Corporate Profile 06 Highlights in 2016 07 06 Responsibility Management 08 Taking People as the foremost: Achieving Common Growth with Employees Respecting Talents and Protecting Basic Rights and Interests 51 Cultivating Talents and Providing Broad Development Space 52 Part I: 50 Retaining Talents and Building Minsheng Homeland 53 From the People, For the People Green Initiative and Environmental Protection: Building Beautiful Ecology Green Credit Guarantees Ecological Progress 57 Integrity for the People: Green Operation Fosters Environmental Protection Culture 58 Adhering to Sustainable Development 56 Green Public Welfare Creates Beautiful Future 61 Optimizing Governance and Regulating Management 13 Holding the Bottom Line and Keeping Stable Development 13 Innovation and Public Welfare: Returning to Shareholders and Creating Values 17 12 Building Harmonious Society Public -

AI Superpowers

Review of AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley and the New World Order by Kai-Fu Lee by Preston McAfee1 Let me start by concluding that AI Superpowers is a great read and well worth the modest investment in time required to read it. Lee has a lively, breezy style, in spite of discussing challenging technology applied to a wide-ranging, thought-provoking subject matter, and he brings great insight and expertise to one of the more important topics of this century. Unlike most of the policy books that are much discussed but rarely read, this book deserves to be read. I will devote my review to critiquing the book, but nonetheless I strongly recommend it. Lee is one of the world’s top artificial intelligence (AI) researchers and a major force in technology startups in China. He was legendary in Microsoft because of his role in Microsoft’s leadership in speech recognition. He created Google’s research office in China, and then started a major incubator that he still runs. Lee embodies a rare combination of formidable technical prowess and managerial success, so it is not surprising that he has important things to say about AI. The book provides a relatively limited number of arguments, which I’ll summarize here: AI will transform business in the near future, China’s “copycat phase” was a necessary step to develop technical and innovative capacity, Success in the Chinese market requires unique customization, which is why western companies were outcompeted by locals, Local Chinese companies experienced “gladiatorial” competition, with ruthless copying, and often outright fraud, but the companies that emerged were much stronger for it, The Chinese government helped promote internet companies with subsidies and encouragement but not favoritism as widely believed, Chinese companies “went heavy” by vertically integrating, e.g. -

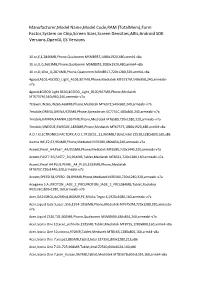

Totalmem),Form Factor,System on Chip,Screen Sizes,Screen Densities,Abis,Android SDK Versions,Opengl ES Versions

Manufacturer,Model Name,Model Code,RAM (TotalMem),Form Factor,System on Chip,Screen Sizes,Screen Densities,ABIs,Android SDK Versions,OpenGL ES Versions 10.or,E,E,2846MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8937,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a 10.or,G,G,3603MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8953,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a 10.or,D,10or_D,2874MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8917,720x1280,320,arm64-v8a 4good,A103,4GOOD_Light_A103,907MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737M,540x960,240,armeabi- v7a 4good,4GOOD Light B100,4GOOD_Light_B100,907MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737M,540x960,240,armeabi-v7a 7Eleven,IN265,IN265,466MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6572,540x960,240,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,DRENA,DRENA,925MB,Phone,Spreadtrum SC7731C,480x800,240,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,KAMBA,KAMBA,1957MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1280,320,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,SWEGUE,SWEGUE,1836MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737T,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a A.O.I. ELECTRONICS FACTORY,A.O.I.,TR10CS1_11,965MB,Tablet,Intel Z2520,1280x800,160,x86 Aamra WE,E2,E2,964MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,480x854,240,armeabi-v7a Accent,Pearl_A4,Pearl_A4,955MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1440,320,armeabi-v7a Accent,FAST7 3G,FAST7_3G,954MB,Tablet,Mediatek MT8321,720x1280,160,armeabi-v7a Accent,Pearl A4 PLUS,PEARL_A4_PLUS,1929MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737,720x1440,320,armeabi-v7a Accent,SPEED S8,SPEED_S8,894MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1280,320,armeabi-v7a Acegame S.A. -

China's Current Capabilities, Policies, and Industrial Ecosystem in AI

June 7, 2019 “China’s Current Capabilities, Policies, and Industrial Ecosystem in AI” Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on Technology, Trade, and Military-Civil Fusion: China’s Pursuit of Artificial Intelligence, New Materials, and New Energy Jeffrey Ding D.Phil Researcher, Center for the Governance of AI Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford Introduction1 This testimony assesses the current capabilities of China and the U.S. in AI, highlights key elements of China’s AI policies, describes China’s industrial ecosystem in AI, and concludes with a few policy recommendations. China’s AI Capabilities China has been hyped as an AI superpower poised to overtake the U.S. in the strategic technology domain of AI.2 Much of the research supporting this claim suffers from the “AI abstraction problem”: the concept of AI, which encompasses anything from fuzzy mathematics to drone swarms, becomes so slippery that it is no longer analytically coherent or useful. Thus, comprehensively assessing a nation’s capabilities in AI requires clear distinctions regarding the object of assessment. This section compares the current AI capabilities of China and the U.S. by slicing up the fuzzy concept of “national AI capabilities” into three cross-sections: 1) scientific and technological (S&T) inputs and outputs, 2) different layers of the AI value chain (foundation, technology, and application), and 3) different subdomains of AI (e.g. computer vision, predictive intelligence, and natural language processing). This approach reveals that China is not poised to overtake the U.S. in the technology domain of AI; rather, the U.S. -

CES 2016 Exhibitor Listing As of 1/19/16

CES 2016 Exhibitor Listing as of 1/19/16 Name Booth * Cosmopolitan Vdara Hospitality Suites 1 Esource Technology Co., Ltd. 26724 10 Vins 80642 12 Labs 73846 1Byone Products Inc. 21953 2 the Max Asia Pacific Ltd. 72163 2017 Exhibit Space Selection 81259 3 Legged Thing Ltd 12045 360fly 10417 360-G GmbH 81250 360Heros Inc 26417 3D Fuel 73113 3D Printlife 72323 3D Sound Labs 80442 3D Systems 72721 3D Vision Technologies Limited 6718 3DiVi Company 81532 3Dprintler.com 80655 3DRudder 81631 3Iware Co.,Ltd. 45005 3M 31411 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing 73108 4DCulture Inc. 58005 4DDynamics 35483 4iiii Innovations, Inc. 73623 5V - All In One HC 81151 6SensorLabs BT31 Page 1 of 135 6sensorlabs / Nima 81339 7 Medical 81040 8 Locations Co., Ltd. 70572 8A Inc. 82831 A&A Merchandising Inc. 70567 A&D Medical 73939 A+E Networks Aria 36, Aria 53 AAC Technologies Holdings Inc. Suite 2910 AAMP Global 2809 Aaron Design 82839 Aaudio Imports Suite 30-116 AAUXX 73757 Abalta Technologies Suite 2460 ABC Trading Solution 74939 Abeeway 80463 Absolare USA LLC Suite 29-131 Absolue Creations Suite 30-312 Acadia Technology Inc. 20365 Acapella Audio Arts Suite 30-215 Accedo Palazzo 50707 Accele Electronics 1110 Accell 20322 Accenture Toscana 3804 Accugraphic Sales 82423 Accuphase Laboratory Suite 29-139 ACE CAD Enterprise Co., Ltd 55023 Ace Computers/Ace Digital Home 20318 ACE Marketing Inc. 59025 ACE Marketing Inc. 31622 ACECAD Digital Corp./Hongteli, DBA Solidtek 31814 USA Acelink Technology Co., Ltd. Suite 2660 Acen Co.,Ltd. 44015 Page 2 of 135 Acesonic USA 22039 A-Champs 74967 ACIGI, Fujiiryoki USA/Dr. -

Intelligent Cities Index China 2020

An initiative of Business School Intelligent Cities Index China 2020 Assessing the artificial intelligence capabilities of Chinese cities An introduction to the six city clusters leading the way on AI Authors: Kai Riemer, Professor of Information Technology and Organisation Sandra Peter, Director Sydney Business Insights Huon Curtis, Senior Research Analyst Kishi Pan, China Analyst Layout and visual design: Nicolette Axiak Contact: [email protected] This report is a publication of Sydney Business Insights at the University of Sydney Business School. Download this report as pdf here: http://sbi.sydney.edu.au/intelligent-cities-index-china/ Full citation: Riemer, Kai; Peter, Sandra; Curtis, Huon; Pan, Kishi (2019) “Intelligent Cities Index China: Assessing the artificial intelligence capabilities of Chinese Cities” Sydney Business Insights, http://sbi.sydney.edu.au/intelligent-cities-index-china/ Cover image: Photo by Minhao Shen on Unsplash, Photo by Yuanbin Du on Unsplash Intelligent Cities Index China Contents Executive overview 5 Background: Artificial intelligence 6 Background: Intelligent cities 12 Study overview 16 Scoring model 18 The Intelligent Cities Index China (ICI-CN) 21 Intelligent City clusters 28 China’s economic regions 29 Intelligent Capital 30 East Coast Challengers 32 Rising Centre 35 Giants of the South 36 Industrial Northeast 38 Developing West 40 References 42 Authors and glossary 43 Page 3 Photo by Hiurich Granja on Unsplash Intelligent Cities Index China Page 4 Photo by Zhang Kaiyv on Unsplash Intelligent Cities Index China Executive overview What is the Intelligent Cities Key insights Index China (ICI-CN)? The Intelligent Cities Index China (ICI-CN) The Intelligent Cities Index China provides a reveals six main clusters of leading cities in ranking of Chinese cities according to their AI. -

Mobvoi WH12018 Ticwatch Pro 3 GPS Smartwatch User Guide

Quick Guide Setting up the TicWatch Pro Syncing with Wear OS by Google ● Turn on the watch and click ‘Start’. Scan the QR code of the watch with your mobile phone to download and install Wear OS by Google, then follow the instructions to sync your phone with the watch. ● You can also download Wear OS by Google from the app store. Managing your watch You can download and install the Mobvoi app, then login with your Mobvoi ID to manage your sports and fitness data. ● Syncing steps ○ Sync the watch with Wear OS by Google. ○ Download the Mobvoi app from Google Play or the iOS app store. ○ Add a new device on the ‘Device’ page of the Mobvoi app and select the corresponding model of smart watch. [Note] You need to use a phone with Android version 6 and above, or iOS version 9.3 and above. If your watch cannot sync with Wear OS by Google app, please reset the watch, restart the phone, disable Bluetooth, enable Bluetooth, and try syncing again. You need to sync the watch with your phone using Wear OS by Google first. When successful, only then can you use the Mobvoi app to connect your phone with the watch. Or else, you will not be able to connect with the Mobvoi app. HW Parameters and Product Specifications Sale name TicWatch Pro 3 GPS Product Smart Watch Model WH12018 Display 1.39' DUAL-LAYER DISPLAY CPU Snapdragon Wear 4100/SDM429w Memory 1GB RAM; 8GB ROM Bluetooth 2.4 GHz, BR/EDR+ BLE WLAN 2.4 GHz,IEEE802.11 b/g/n GNSS GPS/GLONASS/BEIDOU/GALILEO NFC Google pay Battery capacity 3.88v/577mAh OS Wear OS by Google Water proof IP68 TicWatch Pro 3 GPS SmartWatch WH12018 POWERED BY MOBVOI Copyright 2020 Mobvoi Inc. -

Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order Technological, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives

AIR UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order Technological, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives Shazeda Ahmed (UC Berkeley), Natasha E. Bajema (NDU), Samuel Bendett (CNA), Benjamin Angel Chang (MIT), Rogier Creemers (Leiden University), Chris C. Demchak (Naval War College), Sarah W. Denton (George Mason University), Jeffrey Ding (Oxford), Samantha Hoffman (MERICS), Regina Joseph (Pytho LLC), Elsa Kania (Harvard), Jaclyn Kerr (LLNL), Lydia Kostopoulos (LKCYBER), James A. Lewis (CSIS), Martin Libicki (USNA), Herbert Lin (Stanford), Kacie Miura (MIT), Roger Morgus (New America), Rachel Esplin Odell (MIT), Eleonore Pauwels (United Nations University), Lora Saalman (EastWest Institute), Jennifer Snow (USSOCOM), Laura Steckman (MITRE), Valentin Weber (Oxford) Air University Press Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Opening remarks provided by: Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Brig Gen Alexus Grynkewich (JS J39) Names: TBD. and Lawrence Freedman (King’s College, Title: Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order : Techno- London) logical, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives / Nicholas D. Wright. Editor: Other titles: TBD Nicholas D. Wright (Intelligent Biology) Description: TBD Identifiers: TBD Integration Editor: Subjects: TBD Mariah C. Yager (JS/J39/SMA/NSI) Classification: TBD LC record available at TBD AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS COLLABORATION TEAM Published by Air University Press in October -

Retail Branding Marketing Name Device Model AD681H Smartfren

Retail Branding Marketing Name Device Model AD681H Smartfren Andromax AD681H FJL21 FJL21 hws7721g MediaPad 7 Youth 2 10.or D 10or_D D 10.or E E E 10.or G G G 10.or G2 G2 G2 3Go GT10K3IPS GT10K3IPS GT10K3IPS 3Go GT70053G GT70053G GT70053G 3Go GT7007EQC GT7007EQC GT7007EQC 3Q OC1020A OC1020A OC1020A 4good 4GOOD Light B100 4GOOD_Light_B100 Light B100 4good A103 4GOOD_Light_A103 Light A103 7Eleven IN265 IN265 IN265 7mobile DRENA DRENA DRENA 7mobile KAMBA KAMBA KAMBA 7mobile Kamba 2 7mobile_Kamba_2 Kamba_2 7mobile SWEGUE SWEGUE SWEGUE 7mobile Swegue 2 Swegue_2 Swegue 2 A.O.I. ELECTRONICS FACTORY A.O.I. TR10CS1_11 TR10CS1 A1 A1 Smart N9 VFD720 VFD 720 ACE France AS0218 AS0218 BUZZ 1 ACE France AS0518 AS0518 URBAN 1 Pro ACE France AS0618 AS0618 CLEVER 1 ACE France BUZZ_1_Lite BUZZ_1_Lite BUZZ 1 Lite ACE France BUZZ_1_Plus BUZZ_1_Plus BUZZ 1 Plus ACE France URBAN 1 URBAN_1 URBAN 1 ACKEES V10401 V10401 V10401 ACT ACT4K1007 IPBox ACT4K1007 AG Mobile AG BOOST 2 BOOST2 E4010 AG Mobile AG Flair AG_Flair Flair AG Mobile AG Go Tab Access 2 AG_Go_Tab_Access_2 AG_Go_Tab_Access_2 Retail Branding Marketing Name Device Model AG Mobile AG Ultra2 AG_Ultra2 Ultra 2 AG Mobile AGM H1 HSSDM450QC AGM H1 AG Mobile AGM A9 HSSDM450QC AGM A9 AG Mobile AGM X3 T91EUE1 AGM X3 AG Mobile AG_Go-Tab_Access md789hwag AG Go-Tab Access AG Mobile AG_Tab_7_0 AG_Tab_7_0 AG_Tab_7_0 AG Mobile Boost Boost Boost AG Mobile Chacer Chacer Chacer AG Mobile Freedom Access Freedom_Access Freedom Access AG Mobile Freedom E Freedom_E Freedom E AG Mobile Freedom Plus LTE Freedom_Plus_LTE Freedom -

Testimony Before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

July 19, 2018 Testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence China’s Threat to American Government and Private Sector Research and Innovation Leadership Elsa B. Kania, Adjunct Fellow Technology and National Security Center for a New American Security Chairman Nunes, Ranking Member Schiff, distinguished members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss the challenge that China poses to American research and innovation leadership. In my remarks, I will discuss the near-term threat of China’s attempts to exploit the U.S. innovation ecosystem and also address the long-term challenge of China’s advances and ambitions in strategic technologies. In recent history, U.S. leadership in innovation has been a vital pillar of our power and predominance. Today, however, in this new era of strategic competition, the U.S. confronts a unique, perhaps unprecedented challenge to this primacy. Given China’s continued exploitation of the openness of the U.S. innovation ecosystem, from Silicon Valley to our nation’s leading universities, it is imperative to pursue targeted countermeasures against practices that are illegal or, at best, problematic. At the same time, our justified concerns about constraining the transfer of sensitive and strategic technologies to China must not distract our attention from the long-term, fundamental challenge— to enhance U.S. competitiveness, at a time when China is starting to become a true powerhouse and would-be superpower in science and technology (科技强国). China’s Quest for Indigenous Innovation China’s attempts to advance indigenous innovation (自主创新) have often leveraged and been accelerated by tech transfer that is undertaken through both licit and illicit means. -

2019 Edelman Ai Survey

2019 EDELMAN AI SURVEY SURVEY OF TECHNOLOGY EXECUTIVES AND THE GENERAL POPULATION SHOWS EXCITEMENT AND CURIOSITY YET UNCERTAINTY AND WORRIES THAT ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE COULD BE A TOOL OF DIVISION March 2019 Contents 3 Executive Summary 4 Technology 13 Society 25 Business & Government 35 Conclusion 36 Key Takeaways 37 Appendix: Survey Methodology and Profile of Tech Executives 2019 EDELMAN AI SURVEY RESULTS REPORT | 2 Executive Summary Born in the 1950s, artificial intelligence (AI) is hardly AI while nearly half expect the poor will be harmed. new. After suffering an “AI Winter”* in the late 1980s, Approximately 80 percent of respondents expect recent advances with more powerful computers, AI to invoke a reactionary response from those who more intelligent software and vast amounts of “big feel threatened by the technology. Additionally, data” have led to breakneck advances over the last there are also worries about the dark side of AI, several years mostly based on the “deep learning” including concerns by nearly 70 percent about the breakthrough in 2012. Every day, there are headlines potential loss of human intellectual capabilities as extolling the latest AI-powered capability ranging AI-powered applications increasingly make decisions from dramatic improvements in medical diagnostics for us. Furthermore, 7 in 10 are concerned about to agriculture, earthquake prediction, endangered growing social isolation from an increased reliance wildlife protection and many more applications. on smart devices. Nevertheless, there are many voices warning about The survey reveals the many positive benefits but a runaway technology that could eliminate jobs and also the potential that AI can be a powerful tool pose an existential threat to humanity.