Hannah Neufeld Will Be Beginning Her M.A. Studies in the Graduate Program in English This Fall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

G. Robert Stange

Recent Studies in Nineteenth-Century English Literature G. ROBERT STANGE THE FIRST reaction of the surveyor of the year's work in the field of the nineteenth century is dismay at its sheer bulk. The period has obviouslybecome the most recent playground of scholars and academic critics. One gets a sense of settlers rushing toward a new frontier, and at 'times regrets irra- tionally ithe simpler, quieter days. At first glance the massive acocumulation of intellectual labor which I have undertaken to describe seems to display no pattern whatsoever, no evidence of noticeable trends. Yet, to the persistent gazer certain characteristics ultimately reveal themselves. There is a discernible tendency? for example, to lapply the concepts of po'st Existential theology to the work of the Romantic poets; and in general these poets are now being approached with an intellectual excitement which is very different from the diffuse "romantic" enthusiasm of twenty or thirty years ago. It must also be said that the Victorian novelists continue to come into 'their own. lThe kind of serious attention 'thiatit is now assumed Dickens and George Eliot require was a rare thing a decade ago; it is undoubtedly good that this rigorous- thiough sometimes over-solemn-analysis is now being extended to 'some of 'the lesser novelists of the period. It is also still to be noted as an unaccountable oddity th'at reliable editions of even the most important nineteenth-century authors are not always available. Of the novelists 'only Jane Austen has so far 'been critically edited. The Victorian poets, with the exception of Arnold, are in textual chaos, and ;though critical editions of Arnold's and Mill's prose are forthcoming, other prose writers have not 'been much heeded. -

Why Does Daniel Deronda's Mother Live in Russia? Catherine Brown

Why Does Daniel Deronda’s Mother Live In Russia? Catherine Brown Eliot, like Daniel, wanted to avoid “a merely English attitude in studies” (Daniel Deronda [DD] 155). She educated herself to a degree which her critics struggle to match about Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Bohemia, and Palestine -- but not about Russia. In her relative lack of interest in this country she was typical of her own country and time; Lewes’s acquaintance Laurence Oliphant noted in his 1854 account of his travels in Russia that “the scanty information which the public already possesses has been of such a nature as to create an indifference towards acquiring more” (vii). Apart from the works of Turgenev, Eliot is not known to have read any Russian literature, even though Gogol’, Dostoevskii, and Tolstoi would have been available to her in French translation. The take-off decade for English translations of Russian literature started in the year of her death (Brewster 173). Why, then, having hitherto mentioned the country in her fiction only as a source of linseed in The Mill on the Floss, did she choose Russia as the location of Leonora Alcharisi’s second marriage, self-imposed exile from singing and Europe, and emotional and physical decline? Of course, Russia is not simply imposed on Alcharisi by Eliot; she also chose it for herself (this article will treat her and her second husband as though they were real people, in the interests of historical investigation). After the death of her first husband she had suitors of many countries, including Sir Hugo Mallinger, and there is no reason to think that by the age of thirty her options had narrowed to a single man. -

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Author(s): Caroline Wilkinson Source: George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2016), pp. 25-42 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/georelioghlstud.68.1.0025 Accessed: 16-09-2018 23:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies This content downloaded from 73.121.242.252 on Sun, 16 Sep 2018 23:56:41 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Caroline Wilkinson University of Tennessee In both her epic poem The Spanish Gypsy and her final novel Daniel Deronda, Eliot drew upon kabbalistic concepts of the heavens through the characters of Jewish mystics. In the later novel, Eliot moved the mystic, Mordecai, from the narrative’s periphery to its center. This change, symbolically equated within the novel to a shift from geocentricism to heliocentrism, affects time in Daniel Deronda both in terms of plot and historical focus. -

George Eliot on Stage and Screen

George Eliot on Stage and Screen MARGARET HARRIS* Certain Victorian novelists have a significant 'afterlife' in stage and screen adaptations of their work: the Brontes in numerous film versions of Charlotte's Jane Eyre and of Emily's Wuthering Heights, Dickens in Lionel Bart's musical Oliver!, or the Royal Shakespeare Company's Nicholas Nickleby-and so on.l Let me give a more detailed example. My interest in adaptations of Victorian novels dates from seeing Roman Polanski's film Tess of 1979. I learned in the course of work for a piece on this adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel Tess of the D'Urbervilles of 1891 that there had been a number of stage adaptations, including one by Hardy himself which had a successful professional production in London in 1925, as well as amateur 'out of town' productions. In Hardy's lifetime (he died in 1928), there was an opera, produced at Covent Garden in 1909; and two film versions, in 1913 and 1924; together with others since.2 Here is an index to or benchmark of the variety and frequency of adaptations of another Victorian novelist than George Eliot. It is striking that George Eliot hardly has an 'afterlife' in such mediations. The question, 'why is this so?', is perplexing to say the least, and one for which I have no satisfactory answer. The classic problem for film adaptations of novels is how to deal with narrative standpoint, focalisation, and authorial commentary, and a reflex answer might hypothesise that George Eliot's narrators pose too great a challenge. -

George Eliot

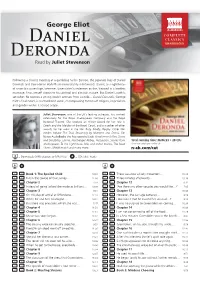

George Eliot COMPLETE CLASSICS Daniel UNABRIDGED Deronda Read by Juliet Stevenson Following a chance meeting at a gambling hall in Europe, the separate lives of Daniel Deronda and Gwendolen Harleth are immediately intertwined. Daniel, an Englishman of uncertain parentage, becomes Gwendolen’s redeemer as she, trapped in a loveless marriage, finds herself drawn to his spiritual and altruistic nature. But Daniel’s path is set when he rescues a young Jewish woman from suicide… Daniel Deronda, George Eliot’s final novel, is a remarkable work, encompassing themes of religion, imperialism and gender within its broad scope. Juliet Stevenson, one of the UK’s leading actresses, has worked extensively for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre. She received an Olivier Award for her role in Death and the Maiden at the Royal Court, and a number of other awards for her work in the filmTruly, Madly, Deeply. Other film credits include The Trial, Drowning by Numbers and Emma. For Naxos AudioBooks she has recorded Lady Windermere’s Fan, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion, Stories from Total running time: 36:06:33 • 28 CDs Shakespeare, To the Lighthouse, Bliss and Other Stories, The Road View our catalogue online at Home, Middlemarch and many more. n-ab.com/cat = Downloads (M4B chapters or MP3 files) = CDs (disc–track) 1 1-1 Book 1: The Spoiled Child 10:08 25 4-5 There was now a lively movement… 13:28 2 1-2 But in the course of that survey… 12:08 26 4-6 Three minutes afterwards… 13:18 3 1-3 Chapter 2 7:58 27 -

Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: a Scandalous Live (BBC2) Daniel Doronda

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2003 Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: A Scandalous Live (BBC2) Daniel Doronda Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Doronda, Daniel, "Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: A Scandalous Live (BBC2)" (2003). The George Eliot Review. 458. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/458 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Daniel Deronda (BBCI) and George Eliot; A Scandalous Life (BBC2) (November-December 2002) The classic novel provides a tempting invitation for the contemporary film-maker: almost certainly it will have period costume, indoor amusements - preferably a dance, even better a ball - lavish, preferably country-house settings, consonant with outdoor amusements like a hunt or at least two or three riding sequences, and moral dilemmas which are often sexual and can be presented in modern terms - the only terms the viewing public is thought to accept. Then there is the plot, which can easily be altered or adjusted - modernized is the cosmetic word - to appeal to viewers who haven't read the novel but like to be associated with its cultural ambience, and viewers who have read it but wish to experience this alternative mode and exercize their critical judgements at the same time. -

No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: the Nineteenth-Century Jewish

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1997 No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot Mary A. Linderman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linderman, Mary A., "No Longer an Alien, the English Jew: The Nineteenth-Century Jewish Reader and Literary Representations of the Jew in the Works of Benjamin Disraeli, Matthew Arnold, and George Eliot" (1997). Dissertations. 3684. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3684 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1997 Mary A. Linderman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO "NO LONGER AN ALIEN, THE ENGLISH JEW": THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY JEWISH READER AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE JEW IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN DISRAELI, MATTHEW ARNOLD, AND GEORGE ELIOT VOLUME I (CHAPTERS I-VI) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY MARY A. LINDERMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY 1997 Copyright by Mary A. Linderman, 1997 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the invaluable services of Dr. Micael Clarke as my dissertation director, and Dr. -

Abstraction and the Subject of Novel-Reading: Drifting Through Romola

Abstraction and the Subject of Novel Reading: Drifting through Romola DAVID KURNICK Two compelling recent accounts of !ctional characterization, perhaps unsurpris- ingly, take George Eliot as their exemplary case. In fact, in the work by Audrey Jaffe and Catherine Gallagher I’m referring to, Eliot’s method of making characters is all about exemplarity itself. To be sure, Jaffe’s The Affective Life of the Average Man and Gallagher’s “George Eliot: Immanent Victorian” differ in many particulars, most profoundly about the issue of how Eliot asks us to feel about the typicality of her characters: Gallagher describes Eliot’s project as “making us want . the quotidian” (73), while Jaffe argues that in Middlemarch “likeness anxiety takes on tragic proportions.” But whether we conceive of typicality as a condition the novels recommend to us or as a nightmarish vision of undifferentiation the novels make us fear, it seems clear that Eliot’s protagonists take their characteristic shape—their shape as characters—by oscillating between the conditions of radical individuality and radical generality. Jaffe and Gallagher both concentrate on Middlemarch, and it is worth noting that in that novel modern character measures itself not only against a vision of the general or the quotidian but also against a gold standard of epic plenitude. I’m referring to the presentation in the novel’s prelude of Dorothea Brooke as a modern—and thus cruelly diminished and averaged out—version of Saint The- resa. This dynamic, whereby we come to know characters by the epic precedents they fail adequately to revive, is given its most overt delineation in Middlemarch, but it features elsewhere in Eliot’s work. -

Hospitality in Silas Marner and Daniel Deronda Josephine Mcdonagh

Hospitality in Silas Marner and Daniel Deronda Josephine McDonagh Nineteenth-century hospitality In Chapter 18 of Daniel Deronda (1876), Mirah, a destitute Jewish woman, enters an unknown household and asks for sanctuary.1 Taken into the ‘full light of the parlour’, she is welcomed with open generosity by ‘four little women’.2 ‘We will take care of you — we will comfort you — we will love you’, is the enthusiastic cry of Mab Meyrick, one of the four. ‘I am a stran- ger. I am a Jewess. You might have thought I was wicked’, is Mirah’s reply (p. 168). Under the ‘full light’ of cosmopolitan embrace, the tripartite pat- tern of Mirah’s speech matches Mab’s and gives the exchange the air of a ritual, framing this moment as though it were a set-piece drama in a novel in which such moments multiply. What is distinctive about this scene of hospitality, which sets it apart from the aristocratic balls and social gather- ings which provide a backdrop of generalized conviviality to so much of the plot, is that it stages a precise cross-cultural encounter of Christian and Jew as though it were an ethical encounter between self and other: Mirah (dubbed both ‘the poor wanderer’ and ‘the bewildered one’ — each name evoking biblical allusions) looks at the ‘four faces’ (evoking the four beasts that drive God’s chariot in the Book of Ezekiel) ‘whose goodwill was being reflected in hers’ (p. 168). There are other, comparable scenes of hospital- ity in the novel: the Cohens’ welcome of Daniel to their modest home in Chapter 34 (‘nothing could be more cordial’ (p. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Iraq & Iran Issue Iran and Iraq: Demography beyond the Jewish Past 6 Sergio DellaPergola AJS, Ahmadinejad, and Me 8 Richard Kalmin Baghdad in the West: Migration and the Making of Medieval Jewish Traditions 11 Marina Rustow Jews of Iran and Rabbinical Literature: Preliminary Notes 14 Daniel Tsadik Iraqi Arab-Jewish Identities: First Body Singular 18 Orit Bashkin A Republic of Letters without a Republic? 24 Lital Levy A Fruit That Asks Questions: Michael Rakowitz’s Shipment of Iraqi Dates 28 Jenny Gheith On Becoming Persian: Illuminating the Iranian-Jewish Community 30 Photographs by Shelley Gazin, with commentary by Nasrin Rahimieh JAPS: Jewish American Persian Women and Their Hybrid Identity in America 34 Saba Tova Soomekh Engagement, Diplomacy, and Iran’s Nuclear Program 42 Brandon Friedman Online Resources for Talmud Research, Study, and Teaching 46 Heidi Lerner The Latest Limmud UK 2009 52 Caryn Aviv A Serious Man 53 Jason Kalman The Questionnaire What development in Jewish studies over the last twenty years has most excited you? 55 AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of the President Please direct correspondence to: Association for Jewish Studies Marsha Rozenblit Association for Jewish Studies University of Maryland Center for Jewish History Editors 15 West 16th Street Matti Bunzl Vice President/Publications New York, NY 10011 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jeffrey Shandler Rachel Havrelock Rutgers University Voice: (917) 606-8249 University of Illinois at Chicago Fax: (917) 606-8222 Vice President/Program E-Mail: [email protected] Derek Penslar Web Site: www.ajsnet.org Editorial Board Allan Arkush University of Toronto Binghamton University AJS Perspectives is published bi-annually Vice President/Membership by the Association for Jewish Studies. -

The Kept Mistress in George Eliot's Daniel Deronda

doi: https://doi.org/10.26262/gramma.v25i0.6594 At Home in Narrative: The Kept Mistress in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda Katie R. Peel University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA Abstract This essay argues that in her novel Daniel Deronda, George Eliot offers her kept mistress character a compassionate context, integrates her into the narrative in a meaningful way, and locates her in the domestic space of a middle-class housewife. She thus performs an intervention on levels of both narrative structure and content that challenges conventional Victorian ideology and creates a new narrative for kept mistresses, who had previously been invisible in both nineteenth-century fiction and nonfiction.1 Keywords: George Eliot, Daniel Deronda, Lydia Glasher, kept mistress, narrative, and domestic space Introduction: Undocumented Women ritish doctor William Acton’s Prostitution, Considered in its Moral, Social & Sanitary Aspects, in London and Other Large Cities with Proposals for the Mitigation and B Prevention of its Attendant Evils (1857) and essayist W. R. Greg’s Prostitution: The Great Sin of Great Cities, (1850, reprinted 1853) proved two of the most popular texts on prostitution, and consequently on women’s sexuality, in the mid-nineteenth century.2 In their essays, a blend of medical, legal, public health, sociological, literary, and moral approaches, both Acton and Greg use Alexandre Parent du Châtelet’s earlier Parisian study as a touchstone, and like du Châtelet, both writers claim that one of the categories of prostitute that cannot be quantified by any census is that of the kept mistress.3 Acton defines the kept mistress as a woman “who has in truth, or pretends to have, but one paramour, with whom she, in some cases, resides” (54), and he positions her in contrast to the “common streetwalker,” who, because she is visible, can be identified and counted.