93 Terns of Short-Range Goals and Long-Range Goals Which Seem to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott

David Richard Hexter Thesis Title: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 Statement of Originality I, David Richard Hexter, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged and my contribution indicated. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the college has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. David R Hexter 12/01/2016 2 Abstract Author: David Hexter, PhD candidate Title of thesis: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott Description The thesis consists of an Introduction, four Chapters and a Conclusion. In the Introduction some of the interpretations that have been offered of Oakeshott’s political writings are discussed. The key issue of interpretation is whether Oakeshott is best considered as a disinterested philosopher, as he claimed, or as promoting an ideology or doctrine, albeit elliptically. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N

fIICTN COMt~W$~bM IWIS ISDI EFJSIKNOF U 2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N. Noble, Ea uiro W?ashamingoD.206 Larec Nr.Noble, sur cashingtonreDsC. 20463 n h leto f hc a~a n the defeat of Senator Frank R. Lautenberg in the 1994 United States Senate election in New Jersey in violation of 2 U.S.C. 5441(b) and 5441(d) Almost every day, Monday through Friday, for four hours a day, 3:00 P.M. to 7:00 P.M. WABC put a paid employee, Bob Grant, on the air who uses the four hours block of time to expressly ad- vocate the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. As you are aware, corporate media have been given a efat exception from 2 U.S.C. §441(b), nL.n. to permit an intermit- tent "editorial" advocating the election of a candidate. Tradi- tionally, that exception has been narrowly construed. WABC has made a decision at the highest levels of corporate policy to allow that "exception" to gobble up the prohibition. By committing four hours of air time during "prime time", 5 days a week, WABC has illegally contributed and subsidized a Federal election in violation of Federal law, expending hundreds of thousands of dollars expressly advocating the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. WABO is believed to be a wholly owned corporation asset of Capi- tal Cities, Inc. which is owned by the American Broadcasting Corp. with offices at 2 Penn Plaza, 17th Floor, New York, NY 10121. -

Manual - Here's a Little Tid Bit on Bob Grant You Might Be Interested In

Subject: Manual - here's a little tid bit on Bob Grant you might be interested in. Posted by Mr Vinyl on Sun, 13 Nov 2005 11:39:16 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message I did a quick search on his name and came up with a biography on him. Here is a small excerpt from the following link. After being fired, Grant then moved down the dial to WOR where he continued to host the same type of show in the same time slot; he would occasionally criticize his WABC replacement Sean Hannity. In the late 1990s his show went into national syndication, trying to follow the lead of Rush Limbaugh and other successful conversative talkers, but few stations picked it up and it reverted to a local show. It would seem your accusation that Rush stole his act from Grant is also wrong. Seems to me that he was trying to follow Rush's lead. Also from what I have read about Grant (I have never listened to him). He is loudmouthed and hangs up on people. Rush never does this so I don't see how you could say Rush stole his "act" from Grant. In what way did Rush steal his act from Grant? **Note - this is your chance to give some facts and not just make wild accusations** http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Grant_(radio) Subject: Re: Manual - here's a little tid bit on Bob Grant you might be interested in. Posted by Manualblock on Sun, 13 Nov 2005 12:45:40 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message Easily; Grant was around on the dial since the late 70's and in radio since the early 70's. -

Constructing Neo-Conservatism

Stephen Eric Bronner Constructing Neo-Conservatism by Stephen Eric Bronner eo-conservatism has become both a code word for reactionary thinking Nin our time and a badge of unity for those in the Bush administration advocating a new imperialist foreign policy, an assault on the welfare state, and a return to “family values.” Its members are directly culpable for the disintegration of American prestige abroad, the erosion of a huge budget surplus, and the debasement of democracy at home. Enough inquiries have highlighted the support given to neo-conservative causes by various businesses and wealthy foundations like Heritage and the American Enterprise Institute. In general, however, the mainstream media has taken the intellectual pretensions of this mafia far too seriously and treated its members far too courteously. Its truly bizarre character deserves particular consideration. Thus, the need for what might be termed a montage of its principal intellectuals and activists. Montage NEO-CONSERVATIVES WIELD EXTRAORDINARY INFLUENCE in all the branches and bureaucracies of the government. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz really require no introduction. These architects of the Iraqi war purposely misled the American public about the existence of weapons of mass destruction, a horrible pattern of torturing prisoners of war, the connection between Saddam Hussein and al Qaeda, the celebrations that would greet the invading troops, and the ease of setting up a democracy in Iraq. But they were not alone. Whispering words of encouragement was the notorious Richard Perle: a former director of the Defense Policy Board, until his resignation amid accusations of conflict of interest, his nickname—“the Prince of Darkness”—reflects his advanced views on nuclear weapons. -

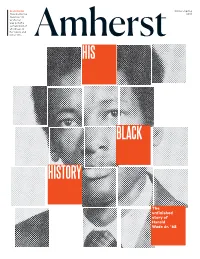

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

One Year Later Harlan Ellison

ONE YEAR LATER HARLAN ELLISON CelebratingCelebrating Reason Reason and and Humanity Humanity SUMMER FALL 2002 • VOL. 22 No. 43 f 23> Paul KURTZ • Wendy KAMINER • Richard DAWKINS • Nat HENTOFF Christopher HITCHENS • Tom FLYNN • Jeannette LOWEN • Taner EDIS 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

RADIO's ROYALTY | APP.Com | Asbury Park Press Page 1 of 3

RADIO'S ROYALTY | APP.com | Asbury Park Press Page 1 of 3 Other editions: Mobile | News Feeds | E-Newsletters Find it: Jobs | Cars | Real Estate | Apartments | Dating | Shopping | Classifieds | Place an Ad All Local News Calendar Jobs More » SPONSORED BY: SEARCH ALL HOME NEWS HOMETOWNS YOUR VOICES OPINION BUSINESS SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT PHOTOS/VIDEO DATA UNIVERSE BUY/SELL CUSTOMER SERVICE NewsFront Updates State Nation & World Living Obituaries Special Sections Politics Weather Submissions Comment, blog & share photos Log in | Become a member RADIO'S ROYALTY Bob Grant gets National Hall of Fame nod BY MAUREEN NEVIN DUFFY • CORRESPONDENT • APRIL 27, 2008 Post a Comment Recommend Print this page E-mail this article SHARE THIS ARTICLE: Del.icio.us Facebook Digg Reddit Newsvine What’s this? On author Arianna Huffington's Huffington Post Web publication, bloggers had a field day when WABC (770 AM) re-hired conservative talk-show host Bob Grant in September. "WABC has wheeled the Grand Kleagle of hate Radio personality Bob Grant says he misses his former haunt, radio, Bob Grant, out of a rest home for vitriolic, the REO Diner in Woodbridge, since moving to the Jersey Shore retrograde talk show hosts," wrote Huffington's in the 1990s. File photo "Off the Bus" blogger, Ken Bank. "After retiring last year from a rival station, Grant joins the network in a line-up that also includes wingnut RELATED NEWS FROM THE WEB stalwarts Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity." LATEST HEADLINES BY TOPIC: Blog News Imagine what they'll say now that Grant's been Abortion nominated for the National Radio Hall of Fame. -

Plenary Panel Protecting the Homeland and Honoring Civil

Plenary Panel Protecting the Homeland and Honoring Civil Liberties: How Can the Constitution Guide Us? Federal Bar Association 2017 Mid-Year Meeting Saturday, March 18, 2017 10:30 AM – Noon Capital Hilton Hotel, Washington, D.C. Background Materials Background Materials …………………………………………………………………….. 1 Program Overview……………….…………………………………………………………. 3 Sahar F. Aziz, Professor Law, Texas A&M University, Fort Worth, TX .. 4 Gwendolyn Keyes Fleming, Esq., Former Principal Legal Advisor (General Counsel), U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Immigration & Customs Enforcement, Washington, D.C. ……… 22 Michael M. Hethmon, Senior Counsel, Immigration Reform Law Institute, Washington, D.C. …………………………………………………………… 31 Executive Order 13780 of March 6, 2017. Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States. 82 Federal Register 13209 (March 9, 2017) ………………………………………………………………… 34 Sahar F. Aziz, Rethinking Counterrorism in the Age of ISIS: Lessons from Sinai, 95 Nebraska Law Review 307 (2016) ………………………………. 45 Sahar F. Aziz, Losing the 'War of Ideas': A Critique of Countering Violent Extremism Programs (February 8, 2017). Texas International Law Journal, Forthcoming ………………………………………………………………… 105 Patrick J. Charles, The Plenary Power Doctrine and the Constitutionality of Ideological Exclusions: An Historical Perspective, 15 Texas Review of Law & Policy 61 (Fall 2010) …………………………………………………...... 129 Congressional Research Service, Executive Authority to Exclude Aliens: In Brief, January 23, 2017 ………………………………………………………………………. 171 Symposium -

Lyndon Larouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC Larouchepac.Com Facebook.Com/Larouchepac @Larouchepac

Lyndon LaRouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC larouchepac.com facebook.com/larouchepac @larouchepac Restoring the Soul of America THE EXONERATION OF LYNDON LAROUCHE Table of Contents Helga Zepp-LaRouche: For the Exoneration of 2 the Most Beautiful Soul in American History Obituary: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. (1922–2019) 9 Selected Condolences and Tributes 16 Background: The Fraudulent 25 Prosecution of LaRouche Letter from Ramsey Clark to Janet Reno 27 Petition: Exonerate LaRouche! 30 Prominent Petition Signers 32 Prominent Signers of 1990s Statement in 36 Support of Lyndon LaRouche’s Exoneration LLPPA-2019-1-0-0-STD | COPYRIGHT © MAY 2019 LYNDON LAROUCHE PAC, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Cover photo credits: EIRNS/Stuart Lewis and Philip Ulanowsky INTRODUCTION For the Exoneration of the Most Beautiful Soul in American History by Helga Zepp-LaRouche There is no one in the history of the United States to my knowledge, for whom there is a greater discrep- ancy between the image crafted by the neo-liberal establishment and the so-called mainstream media, through decades of slanders and co- vert operations of all kinds, and the actual reality of the person himself, than Lyndon LaRouche. And that is saying a lot in the wake of the more than two-year witch hunt against President Trump. The reason why the complete exoneration of Lyn- don LaRouche is synonymous with the fate of the United States, lies both in the threat which his oppo- nents pose to the very existence of the U.S.A. as a republic, and thus for the entire world, it system, the International Development Bank, which and also in the implications of his ideas for America’s fu- he elaborated over the years into a New Bretton Woods ture survival. -

Taxes to Rise $12.3 Mil. Westfield Introduces Town Budget, Considers

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, May 27, 2010 OUR 120th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 21-2010 Periodical – Postage Paid at Rahway, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Westfield Introduces Town Budget, Considers Crossing Guard Cuts By LAUREN S. BARR Salaries and wages have been de- Several residents and members of Specially Written for The Westfield Leader creased by 6 percent over 2009 due to the B.R.A.K.E.S. Group (Bikers Run- WESTFIELD — At Tuesday salary freezes and staffing reductions. ners And Kids are Entitled to Safety) night’s Westfield Town Council meet- The town has a hiring freeze in place questioned the council’s cut of ing, the council passed a resolution to and is not automatically replacing $73,000 from the $600,000 crossing introduce the town’s $39.1-million retirees. Over the past five years, 19 guard budget. municipal budget. The 2010 munici- full-time positions and 28 part-time Councilman Ciarrocca said that 18 pal budget represents an increase of positions have been eliminated. to 20 posts would be reduced or elimi- $181 on the average assessed home During a presentation by officials, nated in September. He said the po- of $185,100. both Town Administrator James lice department recommended the Mayor Andrew Skibitsky thanked Gildea and Finance Committee Chair- reduction of 25 posts and that the those town employees – such as the man Mark Ciarrocca said the town is decisions on which posts to cut will Teamsters, firefighters and non-union already looking to 2011, which could be made by the Public Safety Com- personnel – who “recognized diffi- bring about more budgetary chal- mittee in conjunction with the police cult times” and agreed to salary lenges. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS July 21, 1977 Wage and Price Fluctuation on Old-Age, Sur H.R

24466 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 21, 1977 wage and price fluctuation on old-age, sur H.R. 8480. A bill for the relief of Pranas if such individual reigstered to vote before vivors, and disability insurance benefits, Brazinska.ses; to the Committee on the the date of the election involved. with such benefits being computed on the Judiciary. Add at the end thereof the following new basis of the worker's 10 or less years of By Mr. GIBBONS: sentence: highest earnings; to the Committee on Ways H.R. 8481. A bill for the relief of M. Sgt. Any unit of general local government and Means. George C. Lee, U.S. Air Force; to the Com which establishes any polling place under By Mr. YOUNG of Alaska: mittee on the Judiciary. this subparagraph may require, in its discre H.R. 8478. A bill to amend title 18, United By Mr. JONES of Oklahoma: tion, that any individual who registers to States Code, to make a crime the willful H.R. 8482. A bill for the relief of Magdalen vote under this subsection shall- destruction of any interstate pipeline· sys F. Martin of Broken Arrow, Okla.; to the (1) register to vote at the registration place tem; to the Committee on the Judiciary. Committee on Veterans' Affairs. at which such individual would have been By Mr. GAYDOS: required to register if such individual desired H.J. Res. 552. Joint resolution relating to to register to vote before the d·ate of the elec the publication of economic and social statis tion involved; and tics for Americans of Balta-Slavic origin or AMENDMENTS (ii) vote at a polling place established by such unit of general local government under descent; jointly, to the Committees on Under clause 6 of rule XXIII, proposed Education and Labor, and Post Office and this subparagraph.