Editor Assistant Editors Editorial Board Managing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualify of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualify of the copy submitted. Broken or indisfinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are misang pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an ad&tional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FROM THE NEIGHBORHOOD TO THE NATION: THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF MIDNIGHT BASKETBALL A DOCTORAL DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By VIVIAN L. -

Why the Equal Rights Amendment Is Important

ABSTRACT Even Americans living outside the United States believe that we need to add the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Despite living abroad, we still care and vote in the last U.S. state where we resided. WHY THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT IS IMPORTANT Stories from Americans living abroad Why the Equal Rights Amendment is Important Stories from Americans living Abroad Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Alaska ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 We've come so far and yet... .................................................................................................................... 7 Arizona .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 For my children's future ............................................................................................................................ 8 Before I die ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Arkansas ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 #ERANow.................................................................................................................................................. -

A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott

David Richard Hexter Thesis Title: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 Statement of Originality I, David Richard Hexter, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged and my contribution indicated. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the college has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. David R Hexter 12/01/2016 2 Abstract Author: David Hexter, PhD candidate Title of thesis: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott Description The thesis consists of an Introduction, four Chapters and a Conclusion. In the Introduction some of the interpretations that have been offered of Oakeshott’s political writings are discussed. The key issue of interpretation is whether Oakeshott is best considered as a disinterested philosopher, as he claimed, or as promoting an ideology or doctrine, albeit elliptically. -

2002 NCAA Soccer Records Book

Division I Women’s Records Individual Records .............................................. 194 Team Records ..................................................... 200 Polls ................................................................... 204 194 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS GOALS PER GAME Career Individual Records Season 704—Beth Zack, Marist, 1995-98 (66 games) 1.76—Lisa Cole, Southern Methodist, 1987 (37 in 21 Official NCAA Division I women’s soccer games) SAVES PER GAME records began with the 1982 season and are Career (Min. 40 goals) Season based on information submitted to the NCAA 1.49—Kelly Smith, Seton Hall, 1997-99 (76 in 51 24.1—Chantae Hendrix, Robert Morris, 1992 (241 in statistics service by institutions participating in games) 10 games) the statistics rankings. Career records of players ASSISTS Career include only those years in which they compet- Game 18.25—Dayna Dicesare, Robert Morris, 1993-96 ed in Division I. Annual champions started in 6—Marit Foss, Jacksonville vs. Alabama A&M, Sept. 1, (657 in 36 games) 2000; Anne-Marie Lapalme, Mercer vs. South the 1998 season, which was the first year the GOALS AGAINST AVERAGE NCAA compiled weekly leaders. In statistical Carolina St., Aug. 27, 2000; Holly Manthei, Notre Dame vs. Villanova, Nov. 3, 1996; Colleen Season (Min. 1,200 minutes) rankings, the rounding of percentages and/or McMahon, Cincinnati vs. Mt. St. Joseph, Sept. 20, 0.05—Anne Sherow, North Carolina, 1987 (1 GA in averages may indicate ties where none exist. In 1982 1,712 min.) these cases, the numerical order of the rankings Season Career (Min. 2,500 minutes) is accurate. 44—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1996 (26 games) 0.14—Anne Sherow, North Carolina, 1985-88 (4 GA Career in 2,525 min.) 129—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1994-97 (100 Scoring games) GOALKEEPER MINUTES PLAYED ASSISTS PER GAME 8,853:12—Emily Oleksiuk, Penn St., 1998-01 POINTS Season Game 1.69—Holly Manthei, Notre Dame, 1996 (44 in 26 Miscellaneous 16—Kristen Arnott, St. -

2020 UNC Women's Soccer Record Book

2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book 1 2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book Carolina Quick Facts Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2020 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents, Quick Facts........................................................................ 2 Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2019 Roster, Pronunciation Guide................................................................... 3 2020 Schedule................................................................................................. 4 Enrollment: 18,814 undergraduates, 11,097 graduate and professional 2019 Team Statistics & Results ....................................................................5-7 students, 29,911 total enrollment Misc. Statistics ................................................................................................. 8 Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz Chancellor: Losses, Ties, and Comeback Wins ................................................................. 9 Bubba Cunningham Director of Athletics: All-Time Honor Roll ..................................................................................10-19 Larry Gallo (primary), Korie Sawyer Women’s Soccer Administrators: Year-By-Year Results ...............................................................................18-21 Rich (secondary) Series History ...........................................................................................23-27 Senior Woman Administrator: Marielle vanGelder Single Game Superlatives ........................................................................28-29 -

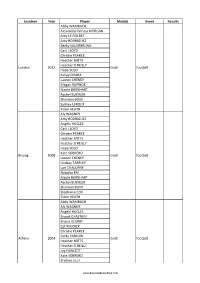

List of All Olympics Prize Winners in Football in U.S.A

Location Year Player Medals Event Results Abby WAMBACH Alexandra Patricia MORGAN Amy LE PEILBET Amy RODRIGUEZ Becky SAUERBRUNN Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY London 2012 Gold football Hope SOLO Kelley OHARA Lauren CHENEY Megan RAPINOE Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Sydney LEROUX Tobin HEATH Aly WAGNER Amy RODRIGUEZ Angela HUCLES Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Hope SOLO Kate SOBRERO Beijing 2008 Gold football Lauren CHENEY Lindsay TARPLEY Lori CHALUPNY Natasha KAI Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Stephanie COX Tobin HEATH Abby WAMBACH Aly WAGNER Angela HUCLES Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Cat REDDICK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Athens 2004 Gold football Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Joy FAWCETT Kate SOBRERO Kristine LILLY www.downloadexcelfiles.com Lindsay TARPLEY Mia HAMM Shannon BOXX Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carla OVERBECK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Danielle SLATON Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kate SOBRERO Sydney 2000 Silver football Kristine LILLY Lorrie FAIR Mia HAMM Michelle FRENCH Nikki SERLENGA Sara WHALEN Shannon MACMILLAN Siri MULLINIX Tiffeny MILBRETT Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carin GABARRA Carla OVERBECK Cindy PARLOW Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kristine LILLY Atlanta 1996 Gold football 5 (4 1 0) 13 Mary HARVEY Mia HAMM Michelle AKERS Shannon MACMILLAN Staci WILSON Tiffany ROBERTS Tiffeny MILBRETT Tisha VENTURINI Alexander CUDMORE Charles Albert BARTLIFF Charles James JANUARY John Hartnett JANUARY Joseph LYDON St Louis 1904 Louis John MENGES Silver football 3 pts Oscar B. BROCKMEYER Peter Joseph RATICAN Raymond E. LAWLER Thomas Thurston JANUARY Warren G. BRITTINGHAM - JOHNSON Claude Stanley JAMESON www.downloadexcelfiles.com Cormic F. COSTGROVE DIERKES Frank FROST George Edwin COOKE St Louis 1904 Bronze football 1 pts Harry TATE Henry Wood JAMESON Joseph J. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N

fIICTN COMt~W$~bM IWIS ISDI EFJSIKNOF U 2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N. Noble, Ea uiro W?ashamingoD.206 Larec Nr.Noble, sur cashingtonreDsC. 20463 n h leto f hc a~a n the defeat of Senator Frank R. Lautenberg in the 1994 United States Senate election in New Jersey in violation of 2 U.S.C. 5441(b) and 5441(d) Almost every day, Monday through Friday, for four hours a day, 3:00 P.M. to 7:00 P.M. WABC put a paid employee, Bob Grant, on the air who uses the four hours block of time to expressly ad- vocate the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. As you are aware, corporate media have been given a efat exception from 2 U.S.C. §441(b), nL.n. to permit an intermit- tent "editorial" advocating the election of a candidate. Tradi- tionally, that exception has been narrowly construed. WABC has made a decision at the highest levels of corporate policy to allow that "exception" to gobble up the prohibition. By committing four hours of air time during "prime time", 5 days a week, WABC has illegally contributed and subsidized a Federal election in violation of Federal law, expending hundreds of thousands of dollars expressly advocating the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. WABO is believed to be a wholly owned corporation asset of Capi- tal Cities, Inc. which is owned by the American Broadcasting Corp. with offices at 2 Penn Plaza, 17th Floor, New York, NY 10121. -

Turner Sports Sales Signs Hyundai Motor America As First Offical Sponsor of Women’S United Soccer Foundation

Hyundai Motor America 10550 Talbert Ave, Fountain Valley, CA 92708 MEDIA WEBSITE: HyundaiNews.com CORPORATE WEBSITE: HyundaiUSA.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TURNER SPORTS SALES SIGNS HYUNDAI MOTOR AMERICA AS FIRST OFFICAL SPONSOR OF WOMEN’S UNITED SOCCER FOUNDATION Chris Hosford Corporate Communications Executive Director (714) 9653470 [email protected] ID: 29044 FOUNTAIN VALLEY, Calif., Sep. 5, 2000 Hyundai Motor America has signed on as the first official sponsor of the Women’s United Soccer Association (WUSA) in a fouryear, categoryexclusive deal, it was announced today by Keith Cutler, executive vice president of Turner Sports Sales. Hyundai will be the official car of the WUSA, which will air on TNT and CNN/Sports Illustrated beginning in April 2001 . “As the first official sponsor of WUSA, Hyundai receives unprecedented brand association with a hot, new franchise that already has a large, loyal fan base,” said Cutler. “The broad scope of the sponsorship affords Hyundai maximum exposure nationally and locally, both onair and offair.” “Once Hyundai had experienced the excitement of the Women’s World Cup in the United States, we knew that women’s soccer had the potential to become an important part of the American sports scene,” said Hyundai Motor America Director of Marketing Paul Sellers. “We’re proud to be the first sponsor of the Women’s United Soccer Association.” “We’re very excited to have Hyundai on board as our first national sponsor,” said Lee Berke, Acting President of the WUSA. “We're glad that Hyundai will receive great value and exposure from their involvement with the WUSA. -

Manual - Here's a Little Tid Bit on Bob Grant You Might Be Interested In

Subject: Manual - here's a little tid bit on Bob Grant you might be interested in. Posted by Mr Vinyl on Sun, 13 Nov 2005 11:39:16 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message I did a quick search on his name and came up with a biography on him. Here is a small excerpt from the following link. After being fired, Grant then moved down the dial to WOR where he continued to host the same type of show in the same time slot; he would occasionally criticize his WABC replacement Sean Hannity. In the late 1990s his show went into national syndication, trying to follow the lead of Rush Limbaugh and other successful conversative talkers, but few stations picked it up and it reverted to a local show. It would seem your accusation that Rush stole his act from Grant is also wrong. Seems to me that he was trying to follow Rush's lead. Also from what I have read about Grant (I have never listened to him). He is loudmouthed and hangs up on people. Rush never does this so I don't see how you could say Rush stole his "act" from Grant. In what way did Rush steal his act from Grant? **Note - this is your chance to give some facts and not just make wild accusations** http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Grant_(radio) Subject: Re: Manual - here's a little tid bit on Bob Grant you might be interested in. Posted by Manualblock on Sun, 13 Nov 2005 12:45:40 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message Easily; Grant was around on the dial since the late 70's and in radio since the early 70's. -

SENATE-Wednesday, August 24, 1994

23898 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE August 24, 1994 SENATE-Wednesday, August 24, 1994 (Legislative day of Thursday, August 18, 1994) The Senate met at 10 a.m., on the ex- At 10:30 a.m., the Senate will resume We are prepared also to vote on the piration of the recess, and was called to debate on the pending crime bill. This majority leader's substitute on the order by the President pro tempore will be the third day of debate. It is my health care bill, and to do that today, [Mr. BYRD]. hope that the Senate will be able to maybe, if we finish the other, or maybe The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The proceed promptly to vote on that meas- tomorrow or Friday or next week. Senate Chaplain, Dr. Richard C. Hal- ure. We want to dispel any perception out verson, will lead the Senate in prayer. I believe that a substantial majority there that somehow Republicans are Dr. Halverson. of Senators favor the bill and will vote not cooperating or not moving ahead. for its passage when given the oppor- We are prepared to move ahead. But we PRAYER tunity to do so. have rights, as every Member has The Chaplain, the Reverend Richard We had a series of meetings yester- rights, and each party has rights, and C. Halverson, D.D., offered the follow- day involving an exchange of proposals we intend to protect those rights. ing prayer: between the distinguished Republican We will have further discussion today Let us pray: leader and myself and other interested on the crime bill and why we believe it In a moment of silent prayer, let us Senators. -

Governmental Restraints on Black Leisure, Social Inequality, and the Privatization of Public Space

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 1998 "Not Just for the Fun of It!" Governmental Restraints on Black Leisure, Social Inequality, and the Privatization of Public Space Regina Austin University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Law and Society Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, Public Economics Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Repository Citation Austin, Regina, ""Not Just for the Fun of It!" Governmental Restraints on Black Leisure, Social Inequality, and the Privatization of Public Space" (1998). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 814. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/814 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES "NOT JUST FOR THE FUN OF IT!": GOVERNMENTAL RESTRAINTS ON BLACI( LEISURE, SOCIAL INEQUALITY, AND THE * PRIVATIZATION OF PUBLIC SPACE REGINA AUSTIN** I. INTRODUCTION I cannot imagine any conception of the black good life that does not allow for a fair measure of leisure. Unfortunately, our legal system has a long way to go before blacks will be able to pursue leisure on a just and equal footing with whites.