The Atlantic As a Vector of Uneven and Combined Development Robbie Shilliam a a Victoria University of Wellington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista MP3 Por Genero

Rock & Roll 1955 - 1956 14668 17 - Bill Justis - Raunchy (Album: 247 en el CD: MP3Albms020 ) (Album: 793 en el CD: MP3Albms074 ) 14669 18 - Eddie Cochran - Summertime Blues 14670 19 - Danny and the Juniors - At The Hop 2561 01 - Bony moronie (Popotitos) - Williams 11641 01 - Rock Around the Clock - Bill Haley an 14671 20 - Larry Williams - Bony Moronie 2562 02 - Around the clock (alrededor del reloj) - 11642 02 - Long Tall Sally - Little Richard 14672 21 - Marty Wilde - Endless Sleep 2563 03 - Good golly miss molly (La plaga) - Bla 11643 03 - Blue Suede Shoes - Carl Perkins 14673 22 - Pat Boone - A Wonderful Time Up Th 2564 04 - Lucile - R Penniman-A collins 11644 04 - Ain't that a Shame - Pat Boone 14674 23 - The Champs - Tequila 2565 05 - All shock up (Estremecete) - Blockwell 11645 05 - The Great Pretender - The Platters 14675 24 - The Teddy Bears - To Know Him Is To 2566 06 - Rockin' little angel (Rock del angelito) 11646 06 - Shake, Rattle and Roll - Bill Haley and 2567 07 - School confidential (Confid de secund 11647 07 - Be Bop A Lula - Gene Vincent 1959 2568 08 - Wake up little susie (Levantate susani 11648 08 - Only You - The Platters (Album: 1006 en el CD: MP3Albms094 ) 2569 09 - Don't be cruel (No seas cruel) - Black 11649 09 - The Saints Rock 'n' Roll - Bill Haley an 14676 01 - Lipstick on your collar - Connie Franci 2570 10 - Red river rock (Rock del rio rojo) - Kin 11650 10 - Rock with the Caveman - Tommy Ste 14677 02 - What do you want - Adam Faith 2571 11 - C' mon everydody (Avientense todos) 11651 11 - Tweedle Dee - Georgia Gibbs 14678 03 - Oh Carol - Neil Sedaka 2572 12 - Tutti frutti - La bastrie-Penniman-Lubin 11652 12 - I'll be Home - Pat Boone 14679 04 - Venus - Frankie Avalon 2573 13 - What'd I say (Que voy a hacer) - R. -

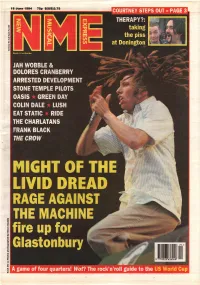

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Atelier Van Lieshout

atelier van lieshout SLAVE CiTY MuseuM FolKWanG atelier van lieshout MuseuM folkwang STADt Der SKLAVEN SLAVE CitY stadt der sklaven / slave city 5 inhaltsverzeiChnis / Contents HARTWIG FISCHER UND/AND SABINE MARIA SCHMIDT Vorwort und Einführung / Foreword and Introduction 6 ALWIN FITTING Die Ausstellung und das Symposium / The Exhibition and the Symposium 10 werke aus Stadt der Sklaven / works froM Slave City 12 SABINE MARIA SCHMIDT Es ist Menschenfleisch! Zum filmischen und literarischen Kontext der Stadt der Sklaven / It's People! On the Filmic and Literary Context of SlaveCity 48 WOUTER VANSTIPHOUT Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Van Lieshout / Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Van Lieshout 58 JOEP VAN LIESHOUT Die Stadt der Sklaven – ein Kommentar / SlaveCity – A Comment 70 ausstellungsDokuMentation / exhibition DoCuMentation 76 verzeiChnis Der ausgestellten werke / list of exhibiteD works 126 sYMposiuM: Die unfreiheit Der zukunft / future bonDage 128 HERFRIED MÜNKLER Nachhaltige Sicherheit, gesicherte Nachhaltigkeit. Die Beobachtung freiwilliger Knechtschaft und die negativen Utopien des 20. Jahrhunderts 131 Sustainable Security, Secured Sustainability. The Observation of Voluntary Servitude and the Negative Utopias of the Twentieth Century 137 MICHAEL ZEUSKE Ein kurzer Abriss über die Weltgeschichte der Sklaverei. Teil I 143 A Short Outline of the History of Slavery. Part I 154 RONALD HITZLER Sklaverei: Ein Lust-Spiel? Rollen und Rituale in sadomasochistischen Arrangements 165 Slavery: A Play of Pleasure? Roles and Rituals in Sadomasochistic Arrangements 171 HARALD WELZER Jeder die Gestapo des anderen. Über totale Gruppen 177 Each the Other’s Gestapo. On Total Groups 183 CLAUS LEGGEWIE Klima-Kommissare. Oder: Müssen Freunde der Erde Feinde des Menschen sein? 190 Climate Inspectors. Or: Do Friends of the Earth have to be Enemies of the People? 202 TANJA DÜCKERS UND ANTON LANDGRAF Wir sind so frei. -

Sepultura Roots Bloody Roots Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sepultura Roots Bloody Roots mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Roots Bloody Roots Country: Australia Released: 1996 Style: Thrash, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1308 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1175 mb WMA version RAR size: 1563 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 135 Other Formats: AC3 VOX ASF AU XM MP4 WMA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Roots Bloody Roots 3:33 Procreation (Of The Wicked) 2 3:39 Written-By – Martin Ain*, Tom Warrior* 3 Propaganda (Live) 3:37 4 Beneath The Remains / Escape To The Void (Live) 3:33 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – The All Blacks B.V. Copyright (c) – The All Blacks B.V. Licensed To – Roadrunner Records Licensed From – The All Blacks B.V. Published By – Roadblock Music, Inc. Published By – Roadster Music B.V. Published By – EMI Blackwood Published By – Maldoror Musikverlag Manufactured By – Combined Creative Services Made By – PMI Credits Bass – Paulo Jr. Co-producer – Sepultura (tracks: 1, 2) Design, Artwork [B&W Montage] – Twelve Point Rule Drums – Igor Cavalera Guitar – Andreas Kisser Mixed By – Andy Wallace (tracks: 1, 2), Scott Burns (tracks: 3, 4) Photography By [B&w] – Gary Monroe Photography By [Cover And Band] – Michael Grecco Producer – Ross Robinson (tracks: 1, 2), Sepultura (tracks: 3, 4) Recorded By, Engineer – Steven Remote (tracks: 3, 4) Vocals, Guitar – Max Cavalera Written-By – Sepultura (tracks: 1, 3, 4) Notes Clone of the Netherlands issue. Main distinguishing characteristics are the matrix information and digipak manufacturer. Track 2 originally performed by Celtic Frost. Tracks 3, 4 recorded live, March 1994, Minneapolis, US. CD is housed in a digipak DIGIPAK Manufactured under exclusive licence from A.G.I., USA, for Australasia by Combined Creative Services. -

Sepultura Chaos AD Mp3, Flac

Sepultura Chaos A.D. mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Chaos A.D. Country: Brazil Released: 1993 Style: Thrash MP3 version RAR size: 1203 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1872 mb WMA version RAR size: 1705 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 426 Other Formats: MMF XM AC3 ASF DXD MP1 DTS Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Refuse / Resist 3:19 Territory 2 4:47 Lyrics By – Andreas Kisser Slave New World 3 2:55 Lyrics By – Evan Seinfeld, Max Cavalera 4 Amen 4:27 5 Kaiowas 3:43 6 Propaganda 3:33 Biotech Is Godzilla 7 1:52 Lyrics By – Jello Biafra Nomad 8 4:59 Lyrics By – Andreas Kisser 9 We Who Are Not As Others 3:42 10 Manifest 4:49 The Hunt 11 3:59 Music By, Lyrics By – New Model Army 12 Clenched Fist 4:58 Chaos B.C. 13 Engineer [Mix Engineer] – Chris FlamRemix, Producer [Additional Produced By] – Roy 5:12 Mayorga Kaiowas [Tribal Jam] 14 3:47 Mixed By – Andy WallaceProducer – Sepultura Territory [Live] 15 4:48 Mixed By – Scott BurnsProducer – SepulturaRecorded By – Steven Remote Amen / Inner Self [Live] 16 8:42 Mixed By – Scott BurnsProducer – SepulturaRecorded By – Steven Remote Companies, etc. Recorded At – Rockfield Studios Recorded At – Chepstow Castle Mixed At – The Wool Hall Mastered At – Sterling Sound Credits A&R – Michael Goldstone, Monte Conner Artwork [Cover Illustration] – Michael R. Whelan Artwork [Sepultribe Chaos Logo] – Igor Cavalera Bass, Drums [Floor Tom] – Paulo Jr. Co-producer – Sepultura Drums, Percussion – Igor Cavalera Engineer [Assistant At Chepstow Castle] – Dave Somers Engineer [Assistant At Rockfield Studios] – Simon Dawson Guitar, Acoustic Guitar [12 String Steel Acoustic], Acoustic Guitar [Nylon Strings Acoustic] – Andreas Kisser Lyrics By – Max Cavalera (tracks: 1, 3 to 6, 9 to 12) Mastered By – George Marino Mixed By, Recorded By – Andy Wallace Music By – Sepultura (tracks: 1 to 10, 12) Producer – Andy Wallace Technician [Guitar Sound/Feedback Advisor] – Alex Newport Vocals [Throat], Guitar [4 String Guitar], Acoustic Guitar [Nylon Strings Acoustic] – Max Cavalera Notes 13 - 14 bonus tracks. -

Train Drivers ’ Union Since 1880

ASLEFJOURNAL DECEMBER 2018 The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen Do you ride on down the hillside in a buggy you have made? The train drivers ’ union since 1880 GS Mick Whelan Rail industry’s in flux ASLEFJOURNAL DECEMBER 2018 The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen UR industry is in flux with several O TOCs rumoured to be ready to hand back the keys, or renegotiate their contracts, and ScotRail already in receipt of next year’s subsidy. Uncertainty over Brexit, and the strength of the euro against the pound, make bidding uncertain. Mick: ‘We have to pass The collapse of the on the lighted flame’ funding model and the 5 11 lack of leadership by the Transport Secretary, compounded by the loss of his number two, Jo News Johnson, who had no grasp of the brief, anyway, hardly inspires confidence. How many franchises are l Tube strike, MSPs vote on nationalisation, 4 on hold? Who can remember the last time a franchise women drivers, and AGS election was awarded? We must now be in double figures for l Kylie does the Loco-Motion as a station 5 the number of direct awards. I have been attacked for announcer and it’s ashes to ashes for Alan suggesting future direct awards should be Pegler. Plus Off the Rails: Melvyn Bragg challenged – legally, industrially, and, possibly, politically. What are they afraid of? What are they l Germany launches first hydrogen train 6 hiding? And, more importantly, what are they offering to keep the facade going? Holyrood had a l Thomas the Tank Engine gets a reboot 7 debate on nationalisation and the SNP and Tories l We told you so – TOCs’ profits plummet 8 showed their true colours, against public opinion, by voting for the status quo. -

Sepultura the Best of Sepultura - Chaos in the Jungle Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sepultura The Best Of Sepultura - Chaos In The Jungle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Best Of Sepultura - Chaos In The Jungle Country: Russia Released: 1997 Style: Thrash MP3 version RAR size: 1709 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1961 mb WMA version RAR size: 1533 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 479 Other Formats: DXD APE MP4 APE MOD RA MIDI Tracklist 1 Refuse / Resist 3:22 2 Troops Of Doom 3:21 3 Roots Bloody Roots 3:34 4 Morbid Visions 2:51 5 Beneath The Remains 4:23 6 Arise 3:21 7 Ramatahatta 4:30 8 Mass Hypnosis 4:23 9 Territory 4:50 10 Bestial Devastation 3:09 11 Meaningless Movements 4:42 12 Escape To The Void 4:42 13 Primitive Future 3:09 14 Slave New World 2:57 15 Dead Embryonic Cells 4:54 16 Straighthate 5:25 17 To The Wall 5:40 18 Biotech Is Godzilla 1:54 Notes Comes with a 4-page insert, all white inside. Same front a Sepultura - The Best Of Sepultura - Chaos In The Jungle. CD is all white with black text. Title on CD is "Best". Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 18666 32666 1 Matrix / Runout: SB 11297 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Best Of Sepultura - VD Not On Label VD Sepultura Chaos In The Jungle (CD, Russia 1997 690127-2 (Sepultura) 690127-2 Comp, Unofficial) The Best Of Sepultura - ES 4342 Sepultura Chaos In The Jungle CD Club ES 4342 Ukraine 1998 (Cass, Comp, Unofficial) The Best Of Sepultura - Not On Label none Sepultura Chaos In The Jungle none Bulgaria Unknown (Sepultura) (Cass, Comp, Unofficial) The Best Of Sepultura - Not On Label none Sepultura Chaos In The Jungle none Ukraine Unknown (Sepultura) (Cass, Comp, Unofficial) The Best Of Sepultura - VD Not On Label VD Sepultura Chaos In The Jungle (CD, Russia Unknown 690127-2 (Sepultura) 690127-2 Comp, Unofficial) Comments about The Best Of Sepultura - Chaos In The Jungle - Sepultura VAZGINO I only got the CD, never had anything else since I bought it from flee market.. -

Entre a Sanfona E a Guitarra Hibridismos E Identidades No Rock’N’Roll E Heavy Metal Nacionais Dos Anos 90

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Humanas Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Área de Concentração: História Cultural Linha de pesquisa: Identidades, Tradições, Processos Dissertação de Mestrado Orientadora: Profª Drª Eleonora Zicari Costa de Brito Entre a sanfona e a guitarra Hibridismos e identidades no rock’n’roll e heavy metal nacionais dos anos 90 Jorge Alexandre Fernandes Anselmo Sobrinho Brasília, março de 2013 Universidade de Brasília Entre a sanfona e a guitarra Hibridismos e identidades no rock’n’roll e heavy metal nacionais dos anos 90 Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Universidade de Brasília, na área de concentração de História Cultural, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Jorge Alexandre Fernandes Anselmo Sobrinho Brasília, março de 2013 Banca Examinadora Profa. Dra. Eleonora Zicari Costa de Brito (PPGHIS/UnB – Orientadora) Profa. Dra. Marcia de Melo Martins Kuyumjian (PPGHIS/UnB) Prof. Dr. Guilherme Bryan (Centro Universitário Belas Artes – SP) Prof. Dra. Nancy Alessio Magalhães (PPGHIS/UnB – Suplente) À mais linda, com seu amor, apoio e paciência infinitos. Too many hands on my time Too many feelings Too many things on my mind When I leave, I don’t know what I’m hoping to find When I leave, I don’t know what I’m leaving behind Muitas mãos no meu tempo / Muitos sentimentos / Muitas coisas em minha mente / Quando partir, não sei o que espero encontrar / Quando partir, não sei o que deixo para trás. (Rush – The Analog Kid, 1982 ) Agradecimentos Antes de tudo, gostaria de agradecer a todos aqueles e aquelas que tornaram este trabalho possível. -

Sepultura Slave New World Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sepultura Slave New World mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Slave New World Country: Netherlands Released: 1994 Style: Thrash MP3 version RAR size: 1852 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1665 mb WMA version RAR size: 1673 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 924 Other Formats: DMF RA AU MMF MP4 WAV ADX Tracklist Hide Credits Slave New World 1 Co-producer – SepulturaLyrics By – Evan Seinfeld, Max CavaleraMusic By – 2:54 SepulturaProducer – Andy Wallace Desperate Cry (Live) 2 6:12 Producer – SepulturaWritten-By – Sepultura Companies, etc. Licensed To – Roadrunner Records Licensed From – The All Blacks B.V. Manufactured By – Dureco Phonographic Copyright (p) – The All Blacks B.V. Copyright (c) – The All Blacks B.V. Published By – Roadblock Music, Inc. Published By – Roadblock Music Published By – Roadster Music B.V. Designed At – Twelve Point Rule Credits Art Direction, Design – LMD Artwork [Tattoo] – Paul Booth Photography By [Cover Photo] – Mike DeFilippo Notes Almost similar to release Sepultura - Slave New World, but D INT code is different. Issued in a cardboard sleeve. To be stored on the RR 2374-5 Sepultura - Slave New World digipak case. Track 1 taken from the LP Chaos A.D. Published by Roadblock Music, Inc. [ASCAP]/Roadster Music B.V. Track 2 previously unreleased. Published by Roadblock Music [ASCAP]/Roadster Music B.V. © 1994 The All Blacks B.V. ℗ 1991, 1992, 1993 The All Blacks B.V. Made in The Netherlands. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 0 16861-2374-3 1 Matrix / Runout: DURECO [01] RRHOES 2374-3 Rights Society: -

Nilton Silva Jardim Junior

Nilton Silva Jardim Junior Maracatu Metálico: influência de ritmos brasileiros na obra das bandas Angra e Sepultura EM/UFRJ 2005 Introdução Não é de hoje que o rock e os ritmos brasileiros flertam entre si num namoro cheio de altos e baixos, porém produzindo frutos extremamente saborosos e originais. Desde a Tropicália, passando por Raul Seixas – pioneiro em injetar a batida do baião no rock, vide Mosca na Sopa - , Jorge Ben Jor, Paralamas do Sucesso e Raimundos, temos uma tradição de mais de trinta anos e misturas, colagens, hibridismo e reinterpretações. Apesar de muitas vezes irregulares e de não ser uma tendência majoritária na cena nacional, essas fusões são uma verdadeira constante na história do rock nacional. Mais recentemente, esta mistura conseguiu atingir patamares inimagináveis ao se fundir a tendências mais pesadas do rock como o hardcore e o hevy metal. Este último então teve resultado de uma verdadeira bomba pois, apesar de um estilo relativamente recente1, é tido como um dos mais conservadores e “estrangeiros” dos diversos desdobramentos que o gênero teve; devido ao purismo de seus fãs. Pare se ter uma ideia, apesar de desde a Jovem Guarda existirem bandas brasileiras cantando rock em português, isto é uma raridade dentro do estilo e é uma exigência quase obrigatória dos fãs que as bandas cantem em inglês. Não bastasse este purismo em relação as letras, há toda uma cobrança para que as bandas se atenham aos determinantes estéticos e musicais do estilo, limitando o potencial criativo dos artistas. Porém, nos anos noventa duas bandas conseguiram explorar um universo até então desconhecido para estes ritmos, sem quebrar com os padrões “metálicos” conseguindo respeito da crítica especializada e dos fãs: Angra e o Sepultura. -

Voutilainen, Sami

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Trepo - Institutional Repository of Tampere University Personoitujen suositusten monipuolisuus ja kuuntelijamäärät musiikkisuoratoistopalveluissa Sami Voutilainen Tampereen yliopisto Luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietojenkäsittelytiede Pro gradu -tutkielma Ohjaaja: Mikko Ruohonen Joulukuu 2018 i Tampereen yliopisto Luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietojenkäsittelytiede VOUTILAINEN, SAMI: Personoitujen suosituksien monipuolisuus ja kuuntelijamäärät musiikkisuoratoistopalveluissa Pro gradu -tutkielma, 46 sivua, 11 liitesivua Joulukuu 2018 Tieto- sekä verkkotekniikan kehittymisen vuoksi monilla aloilla on jouduttu sopeutumaan uuteen todellisuuteen. Musiikkiteollisuudessa äänitteiden kuuntelun sekä jakelun siirtyessä digitaaliseen levitykseen, on näiden musiikkiin keskittyneiden verkkosovellusten toimintaperiaatteiden tutkimisen merkitys myös kasvanut. Suoratoistopalvelut ovat mahdollistaneet jättimäisen musiikkivalikoiman saapumisen vain muutaman klikkauksen päähän, joka puolestaan on luonut tarpeen kehittää keinoja massiivisen tietomäärän hallintaan. Tyypillinen tapa laajojen katalogien hallintaan on ollut käyttäjätietojen kerääminen ja niiden pohjalta ainoastaan mielenkiintoisen sisällön esittäminen kullekin käyttäjälle. Kun palveluja aletaan personoida, herää kuitenkin huoli käyttäjäryhmien kuplautumisesta, jolloin sisältöä käyttäjälle tulkittujen mieltymyksien ulkopuolelta ei välttämättä nosteta esille enää lainkaan. Suositusjärjestelmien merkityksen uuden musiikin löytämistyökaluna -

Sepultura Chaos AD Mp3, Flac

Sepultura Chaos A.D. mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Chaos A.D. Country: Japan Released: 1993 Style: Thrash, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1249 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1681 mb WMA version RAR size: 1366 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 418 Other Formats: VQF TTA AC3 MP3 MP1 MIDI RA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Refuse / Resist 3:19 2 Territory 4:45 3 Slave New World 2:54 4 Amen 4:24 Kaiowas 5 3:32 Engineer [Assistant] – Dave Somers 6 Propaganda 3:31 Biotech Is Godzilla 7 1:52 Lyrics By – Jello Biafra 8 Nomad 4:58 9 We Who Are Not As Others 3:43 10 Manifest 4:55 The Hunt 11 3:58 Written-By – New Model Army 12.0 Clenched Fist 4:57 12.1 No Audio 1:03 12.2 Untitled 2:02 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – The All Blacks B.V. Copyright (c) – The All Blacks B.V. Licensed To – Roadrunner Records Licensed From – The All Blacks B.V. Published By – Roadblock Music, Inc. Published By – Roadster Music Published By – Attack Attack Music Recorded At – Rockfield Studios Recorded At – Chepstow Castle Mixed At – The Wool Hall Mastered At – Sterling Sound Pressed By – Sonopress – H-3241 Credits A&R – Michael Goldstone, Monte Conner Art Direction – Ioannis , Liz Vap Artwork [CD Label Art] – Paul Booth Bass, Percussion [Floor Tom] – Paulo Jr. Co-producer – Sepultura Drums, Percussion, Artwork [Sepultribe Chaos Logo] – Igor Cavalera Engineer [Assistant] – Simon Dawson Illustration [Cover Illustration] – Michael R. Whelan Lyrics By – Andreas Kisser (tracks: 2, 8), Evan Seinfeld (tracks: 3), Jello Biafra (tracks: 7), Max Cavalera (tracks: 1, 3 to 6, 9 to 12.0) Mastered By – George Marino Music By – Sepultura (tracks: 1 to 10, 12.0) Photography By [Band Photography] – Gary Monroe Photography By [Carandiru Massacre] – Sergio Andrade Producer, Mixed By, Recorded By – Andy Wallace Vocals, Guitar, Acoustic Guitar [Nylon Strings, 12 String Steel] – Andreas Kisser Vocals, Guitar, Acoustic Guitar [Nylon Strings] – Max Cavalera Notes RR 90002 is printed on the bottom of the last page in the booklet.