Game Title: the Missing: J.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020 1

THUNDERFUL GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 GAMES | DISTRIBUTION WWW.THUNDERFULGROUP.COM THUNDERFUL GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2020 2 This is a translation of the Swedish Annual Report. In the event of discrepancies, the Swedish version takes precedence. CONTENT ABOUT THUNDERFUL GROUP ....................................................... 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT ...................................... 33 CEO COMMENT .............................................................................. 5 THE SHARE ..................................................................................... 38 GROUP STRATEGY & TARGETS ......................................................7 NOTES .............................................................................................50 BUSINESS SEGMENT GAMES ........................................................11 AUDITORS REPORT ........................................................................70 BUSINESS SEGMENT DISTRIBUTION ..........................................19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................................73 INVESTMENT CASE ....................................................................... 23 MANAGEMENT ............................................................................... 75 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT ............................................................. 24 OTHER INFORMATION ..................................................................76 BOARD OF DIRECTORS REPORT .............................................. -

Weekends Became Something Other People Did”: Understanding and Intervening in The

“Weekends became something other people did”: Understanding and intervening in the habitus of video game crunch Dr. Amanda C. Cote, [email protected] (Corresponding Author) Mr. Brandon Harris, [email protected] University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Sage in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies on March 26, 2020, available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1354856520913865. Abstract “Crunch”— a period of unpaid overtime meant to speed up lagging projects— is a common labor practice in the video game industry and persists despite many costs to developers. To understand why, we conducted a critical discourse analysis of Game Developer magazine (2000- 2010) to explore how industry members perceive and discuss gamework 1) in a publication for developers, by developers and 2) during the first decade in which serious conversations about labor emerge in the games industry. Our analysis found that many gameworkers treat crunch as “inevitable” due to three specific themes: games as an unmanageable creative industry, an anti- corporate ethos, and a stereotypical developer identity based on passion and perfectionism. These constructions— combined with the industry’s project-based nature and cultures of passion and secrecy— build crunch into the habitus of gamework, helping reproduce exploitative labor practices. However, habitus can and does change over time, providing interested employees, companies, and labor organizers a means to intercede in existing work practices. We suggest a multi-pronged intervention that could build a healthier, more sustainable habitus of gamework. Keywords Video games, media industries, labor practices, habitus, critical discourse analysis, press analysis, game studies, crunch 1 Introduction “All-nighters and seven-day weeks are a fool’s game. -

Reader Agency and Intimacy in Contemporary Horror Fiction

“This Is Not For You” Reader Agency and Intimacy in Contemporary Horror Fiction Aslak Rustad Hauglid A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts Degree UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Spring 2016 II “This Is Not For You” Reader Agency and Intimacy in Contemporary Horror Fiction Aslak Rustad Hauglid A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts Degree Spring 2016 III © Aslak Rustad Hauglid 2016 “This Is Not For You”: Reader Agency and Intimacy in Contemporary Horror Fiction Aslak Rustad Hauglid http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This thesis examines how recent/contemporary horror fiction uses the establishment of reader intimacy and challenges to reader agency in order to create experiences of horror. The discussion focuses on a selection of horror texts from different media published between 2000 and 2016. The thesis argues that these two techniques have come to be increasingly important horror tropes over this period, and examines how they are applied in order to propose a new perspective for understanding how contemporary horror operates. Two central arguments structure this discussion. The first argument is a claim that the aesthetic, narrative and in some case interactive dimensions of the examined horror texts illustrate how these texts seek to shorten the distance between reader and author, while simultaneously questioning the power the reader possesses in relation to the text. All of this takes place in the pursuit of creating an effective experience of horror. -

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan Kirkland Introduction The title of this article is drawn from Philip Brophy’s 1983 essay which coins the neologism ‘horrality’, a merging of horror, textuality, morality and hilarity. Like Brophy’s original did of 1980s horror cinema, this article examines characteristics of survival horror videogames, seeking to illustrate the relationship between ‘new’ (media) horror and ‘old’ (media) horror. Brophy’s term structures this investigation around key issues and aspects of survival horror videogames. Horror relates to generic parallels with similarlylabelled film and literature, including gothic fiction, American horror cinema and traditional Japanese culture. Textuality examines the aesthetic qualities of survival horror, including the games’ use of narrative, their visual design and structuring of virtual spaces. Morality explores the genre’s ideological characteristics, the nature of survival horror violence, the familial politics of these texts, and their reflection on issues of institutional and bodily control. Hilarity refers to moments of humour and self reflexivity, leading to consideration of survival horror’s preoccupation with issues of vision, identification, and the nature of the videogame medium. ‘Survival horror’ as a game category is unusual for its prominence within videogame scholarship. Indicative of the amorphous nature of popular genres, Aphra Kerr notes: ‘game genres are poorly defined and evolve as new technologies and fashions emerge’;(2) an observation which applied as much to videogame academia as to the videogame industry. Within studies of the medium, various game types are commonly listed. These might include the shoot‘emup, the racing game, the platform game, the God game, the realtime strategy game, and the puzzle game,(3) the simulation, roleplaying, fighting/action, sports, traditional and ‘”edutainment”’ game,(4) or action, adventure, strategy and ‘processorientated’ games.(5) These clusters of game types tend to be broad, commonsensical, and undertheorized. -

Not of Woman Born: Monstrous Interfaces and Monstrosity in Video Games

NOT OF WOMAN BORN: MONSTROUS INTERFACES AND MONSTROSITY IN VIDEO GAMES By LAURIE N. TAYLOR A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Laurie N. Taylor To Pete. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have many people to thank for this dissertation: my friends, family, and teachers. I would also like to thank the University of Florida for encouraging the study of popular media, with a high level of critical theory and competence. This dissertation also would not have been possible without the diligent help and guidance from my committee members, Donald Ault and Jane Douglas, as well as numerous other faculty members and graduate students both at the University of Florida and at other institutions. Thanks go to friends and loved ones (and cats): Colin, Jeremiah, Nix, Galahad, and Mila. And, thanks go always to Pete, for helping with research, discussion, giving me love and support, and for being wonderful. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..............................................................................................iv ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................viii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................1 Introduction..............................................................................................................1 -

Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design

The London School of Economics and Political Science Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design Siobhán Thomas A thesis submitted to the Department of Management of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 66,515 words. 2 Abstract The aim of this qualitative research study was to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of game designers from the particular vantage point of intersomatic awareness. Intersomatic awareness is an interbodily awareness based on the premise that the body of another is always understood through the body of the self. While the term intersomatics is related to intersubjectivity, intercoordination, and intercorporeality it has a specific focus on somatic relationships between lived bodies. This research examined game designers’ body-oriented design practices, finding that within design work the body is a ground of experiential knowledge which is largely untapped. To access this knowledge a hermeneutic methodology was employed. The thesis presents a functional model of intersomatic awareness comprised of four dimensions: sensory ordering, sensory intensification, somatic imprinting, and somatic marking. -

Conference Booklet

30th Oct - 1st Nov CONFERENCE BOOKLET 1 2 3 INTRO REBOOT DEVELOP RED | 2019 y Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned Warmest welcome to first ever Reboot Develop it! And we are here to stay. Our ambition through Red conference. Welcome to breathtaking Banff the next few years is to turn Reboot Develop National Park and welcome to iconic Fairmont Red not just in one the best and biggest annual Banff Springs. It all feels a bit like history repeating games industry and game developers conferences to me. When we were starting our European older in Canada and North America, but in the world! sister, Reboot Develop Blue conference, everybody We are committed to stay at this beautiful venue was full of doubts on why somebody would ever and in this incredible nature and astonishing choose a beautiful yet a bit remote place to host surroundings for the next few forthcoming years one of the biggest worldwide gatherings of the and make it THE annual key gathering spot of the international games industry. In the end, it turned international games industry. We will need all of into one of the biggest and highest-rated games your help and support on the way! industry conferences in the world. And here we are yet again at the beginning, in one of the most Thank you from the bottom of the heart for all beautiful and serene places on Earth, at one of the the support shown so far, and even more for the most unique and luxurious venues as well, and in forthcoming one! the company of some of the greatest minds that the games industry has to offer! _Damir Durovic -

Juuma Houkan Accele Brid Ace Wo Nerae! Acrobat Mission

3X3 EYES - JUUMA HOUKAN ACCELE BRID ACE WO NERAE! ACROBAT MISSION ACTRAISER HOURAI GAKUEN NO BOUKEN! - TENKOUSEI SCRAMBLE AIM FOR THE ACE! ALCAHEST THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN - LETHAL FOES ANGELIQUE ARABIAN NIGHTS - SABAKU NO SEIREI-O ASHITA NO JOE CYBERNATOR BAHAMUT LAGOON BALL BULLET GUN BASTARD!! BATTLE SOCCER - FIELD NO HASHA ANCIENT MAGIC - BAZOO! MAHOU SEKAI BING BING! BINGO BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON - ANOTHER STORY SAILOR MOON R BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON SUPER S - FUWA FUWA PANIC BRANDISH 2 - THE PLANET BUSTER BREATH OF FIRE II - SHIMEI NO KO BS CHRONO TRIGGER - MUSIC LIBRARY CAPTAIN TSUBASA III - KOUTEI NO CHOUSEN CAPTAIN TSUBASA V - HASH NO SHOUGOU CAMPIONE CARAVAN SHOOTING COLLECTION CHAOS SEED - FUUSUI KAIROKI CHOU MAHOU TAIRIKU WOZZ CHRONO TRIGGER CLOCK TOWER CLOCKWERX CRYSTAL BEANS FROM DUNGEON EXPLORER CU-ON-PA SFC CYBER KNIGHT CYBER KNIGHT II - CHIKYUU TEIKOKU NO YABOU CYBORG 009 DAI 3 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAI 4 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAIKAIJ MONOGATARI DARK HALF DARK LAW - THE MEANING OF DEATH DER LANGRISSER DIGITAL DEVIL STORY 2 - SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI II DONALD DUCK NO MAHOU NO BOUSHI DORAEMON 4 DO RE MI FANTASY - MILON NO DOKIDOKI DAIBOUKEN DOSSUN! GANSEKI BATTLE DR. MARIO DRAGON BALL Z - HYPER DIMENSION DRAGON BALL Z - CHOU SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN 3 DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - TOTSUGEKI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - KAKUSEI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON QUEST I AND II DRAGON QUEST III - SOSHITE DENSETU E... DRAGON QUEST V - TENKUU NO HANAYOME -

Gratis. Kalo Jauh Kena Ongkos Kirim Rp

GROSIR GAMES Rp.5rb per disk/kaset/dvd bisa di kirim ke tempat / Cash on delivery ( COD ) gratis. kalo jauh kena ongkos kirim Rp.5rb :) Contact Person : - 0896 5606 5690 ================================================================= --> Update Games 2014 s/d Juni 2014 : Murdered Souls Suspect 3dvd State of Decay Lifeline 1dvd Wolf Among Us episode 4 1dvd Watch Dogs 4dvd Killer Is Dead 4dvd Wolfenstein New Order 10dvd Van Helsing 2 6dvd Tropico 5 1dvd Hegemony of Rome Rise of Caesar 1dvd Transistor 1dvd Dinasty Warrior 8 4dvd Dread Out full version 1dvd Walking Dead Season 2 Episode 3 1dvd Outlast Whistleblower 2dvd Bound By Flame 2dvd Amazing Spiderman 2 3dvd Daylight 1dvd Dark Souls 2 3dvd Child of Light 1dvd Trial Fusion 2dvd Warlock 2 1dvd Strike Suit Zero 2dvd Wargame Red Dragon 4dvd Agarest Generations of War Zero 2dvd Lego Hobbit 2dvd Halo Spartan Assault 1dvd Age Of Wonders III 1dvd Batman Arkham Origins Blackgate 1dvd Wolf Among Us episode 3 1dvd Simcity Digital Deluxe 2014 1dvd Bioshock Infinite DLC Burial at Sea episode 2 6dvd Castlevania Mirror of Fate 1dvd Total War Rome 2 Hannibal at the Gate 3dvd MXGP 1dvd Cabelas Big Game Pro Hunter 1dvd Castlevania 2 Lord of Shadow DLC Revelations 2dvd Ether One 1dvd Breach And Clear 1dvd IHF Handball Challenge 1dvd Betrayer 1dvd Devil May Cry 2013 Complete Edition 3dvd ARMA III Full Campaign 3dvd Ninja Gaiden Yaiba 2dvd Deus Ex The Fall 1dvd Typing of Dead Overkill 2dvd Walking Dead 2 episode 1-2 1dvd Southpark Stick of Truth 1dvd Resident Evil 4HD 3dvd Thief 4dvd Castlevania Lord -

GAME NAME 1941 1942 1943 1944 102 Dalmatians 3D 1941J Set1

GAME NAME 1941 1942 1943 1944 102 Dalmatians 3D 1941j set1 1941j set2 1942h 1943b 1943Kai 1944j 19XX 19xxj 2020 Super Baseball 3 Count Bout 3 Count Bout 3 Ninjas Kick Back 3stooges 3x3 Eyes-Juuma Houkan 4 Fun in 1 4 Fun in 1 40love 4-D Warriors 4-D Warriors 4-nin Shougi 64Th Street 64Th Street 6-Pak 76 in 1 88games 8ballac 90 Tank 96ZenkokuKoukouSoccerSenshuken Aaahh! Real Monsters AAAHH!!! Real Monsters Aburner2 Ace wo Nerae Acrobat Mission Acrobat Mission Acrobat Mission Act-Fancer Actfancrj Actfancrj Action 52 Action bass 3D Action Fighter Action Fighter Action Pachio ActRaiser ActRaiser 2 Addams Family Addams Family(USA) Adventures of Batman-Robin Adventures of TomSawyer Adventures of Yogi Bear Adventurous Boy-MaoXianXiaoZi Aero Blasters Aero Fighters Aero Fighters (USA) Aero Fighters 2 Aero Fighters 3 Aero the Acro-Bat Aero the Acro-Bat (USA) Aero the Acro-Bat 2 Aero the Acro-Bat 2 (USA) Aerobiz (USA) Aerobiz Supersonic (USA) After Burner II Aguri Suzuki F1 SuperDriving Air Attack Air Buster Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Air Cavalry Air Gallet Air galletj set1 Air galletj set2 Airbustrj Airbustrj Airduel Airwolf Ajax Akumajou Dracula Akumajou Dracula XX Albert Odyssey Albert Odyssey 2 ALCAHEST Alex Kidd Alex Kidd Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle Alfred Chicken Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Alice no Paint Adventure Alien 3 Alien Soldier Alien Storm Alien Storm 2 Alien Storm 2 Alien Syndrome Alien Syndrome Alien vs Predator Alien Vs. Predator Alien Vs. Predator (3P) Alienchac Aliens Aliens Aliens Aliens vs Predator (Japan) Alisia -

Ludic Dysnarrativa: How Can Fictional Inconsistency in Games Be Reduced? by Rory Keir Summerley

Ludic Dysnarrativa: How Can Fictional Inconsistency In Games Be Reduced? by Rory Keir Summerley A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at the University of the Arts London In Collaboration with Falmouth University December 2017 Abstract The experience of fictional inconsistencies in games is surprisingly common. The goal was to determine if solutions exist for this problem and if there are inherent limitations to games as a medium that make storytelling uncommonly difficult. Termed ‘ludic dysnarrativa’, this phenomenon can cause a loss of immersion in the fictional world of a game and lead to greater difficulty in intuitively understanding a game’s rules. Through close textual analysis of The Stanley Parable and other games, common trends are identified that lead a player to experience dysnarrativa. Contemporary cognitive theory is examined alongside how other media deal with fictional inconsistency to develop a model of how information (fictional and otherwise) is structured in media generally. After determining that gaps in information are largely the cause of a player feeling dysnarrativa, it is proposed that a game must encourage imaginative acts from the player to prevent these gaps being perceived. Thus a property of games, termed ‘imaginability’, was determined desirable for fictionally consistent game worlds. Many specific case studies are cited to refine a list of principles that serve as guidelines for achieving imaginability. To further refine these models and principles, multiplayer games such as Dungeons and Dragons were analysed specifically for how multiple players navigate fictional inconsistencies within them. While they operate very differently to most single-player games in terms of their fiction, multiplayer games still provide useful clarifications and principles for reducing fictional inconsistencies in all games. -

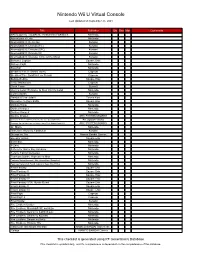

Nintendo Wii U Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii U Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Ōgon no Taiyō: Hirakareshi Fūin Nintendo Adventures of Lolo Nintendo Akumajō Densetsu Konami Akumajō Dracula (FC) Konami Akumajō Dracula (SFC) Konami Akumajō Dracula XX Konami Akumajō Dracula: Circle of the Moon Konami Bahamut Lagoon Square Enix Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Breath of Fire II: Shimei no Ko Capcom Breath of Fire: Ryū no Senshi Capcom Bubble Bobble Square Enix Chou Makaimura Capcom Clock Tower Sunsoft Clu Clu Land: Welcome to New Clu Clu Land Nintendo Contra Spirits Konami Daikōkai Jidai II Tecmo Koei Densetsu no Ogre Battle Square Enix Donkey Kong Nintendo Donkey Kong 3 Nintendo Donkey Kong Jr. Nintendo Double Dragon ARC SYSTEM WORKS Downtown Nekketsu Kōshinkyoku: Soreyuke Daiundōkai Arc System Works Downtown Special: Kunio-kun no Jidaigeki da yo Zenin Shūgō! ARC SYSTEM WORKS Dr. Mario Nintendo Dracula II: Noroi no Fūin Konami Druaga no Tou Namco Bandai Games Elevator Action Square Enix Excitebike Nintendo F-Zero Nintendo F-Zero for Game Boy Advance Nintendo F-Zero: Falcon Densetsu Nintendo Famicom Bunko: Hajimari no Mori Nintendo Famicom Mukashibanashi: Shin Onigashima (Zengohen) Nintendo Famicom Tantei Club Part II: Ushiro ni Tatsu Shōjo Nintendo Final Fantasy Square Enix Final Fantasy II Square Enix Final Fantasy III Square Enix Final Fantasy IV Square Enix Final Fantasy USA: Mystic Quest Square Enix Final Fantasy V Square Enix Final Fantasy VI Square Enix Final Fight Capcom Final Fight 2 Capcom Final Soldier Konami Fire Emblem Gaiden Nintendo Fire Emblem: Monshō no Nazo Nintendo Fire Emblem: Seima no Kōseki Nintendo Fire Emblem: Seima no Kouseki Nintendo Fire Emblem: Seisen no Keifu Nintendo Fire Emblem: Thracia 776 Nintendo Gakkou de atta Kowai Hanashi NAMCO BANDAI Games Inc.