Russian Weapons Sales to Iran Why They Are Unlikely to Stop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Exhibition of Arm in Accordance with the Decisi Armenia

Release for International Exhibition of Arms and Defence Technologies “ ArmHiTec-2020” In accordance with the decision of the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Armenia, the Third International Exhibition of Arms and Defence Technologies “ArmHiTec- 2020" will be held in the period 26-28 March, 2020 at the Exhibition Complex "ErevanEXPO" (Yerevan, Republic of Armenia). The main objective of the International Exhibition of Arms and Defence Technologies “ArmHiTec-2020" is to develop military-economic and strategic partnership of the Republic of Armenia with its partner-countries, as well as to develop high -tech industry spheres. In 2020 the exhibition broadens its thematic sections. Along with the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Armenia the co-organizers of the event are: - MOD of the Republic of Armenia State Military Industry Committee, being aimed at financing the military, scientific research projects, as well as end products. It allows the Committee to work closely with IT companies, carrying out the contracts in the spheres of hi- tech industries. - Ministry of Hi-Tech Industry of the Republic of Armenia, being primarily the digital sphere, military and hi-tech industries. Within the Ministry a new department, responsible for military-technical cooperation with foreign countries is currently being created. The thematic sections of the exhibition have been completed with IT tech, cyber security, engineering labs, and creative centers sections to contribute to the department’s goals realization . The Second International Exhibition of Arms and Defence Technologies “ArmHiTec - 2018” was held in a period from 29 to 31 of March on the territory of “YerevanExpo” center in the capital city of the Republic of Armenia. -

Innovations and Technologies for the Navy and Maritime Areas

Special analytical export project of the United Industrial Publishing № 04 (57), June 2021 GOOD RESULT ASSAULT BOATS IDEX / NAVDEX 2021 QATAR & SPIEF-2021 Military Technical Russian BK-10 Russia at the two Prospective mutually Cooperation in 2020 for Sub-Saharan Africa expos in Abu Dhabi beneficial partnership .12 .18 .24 .28 Innovations and technologies for the navy and maritime areas SPECIAL PARTNERSHIP CONTENTS ‘International Navy & Technology Guide‘ NEWS SHORTLY № 04 (57), June 2021 EDITORIAL Special analytical export project 2 One of the best vessels of the United Industrial Publishing 2 Industrial Internet of ‘International Navy & Technology Guide’ is the special edition of the magazine Things ‘Russian Aviation & Military Guide’ 4 Trawler Kapitan Korotich Registered in the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information 4 Finance for 5G Technology and Mass Media (Roscomnadzor) 09.12.2015 PI № FS77-63977 Technology 6 The largest propeller 6 Protection From High-Precision Weapons 8 New Regional Passenger Aircraft IL-114-300 The magazine ‘Russian Aviation & Military Guide’, made by the United Industrial 8 Klimov presents design of Publishing, is a winner of National prize ‘Golden Idea 2016’ FSMTC of Russia VK-1600V engine 10 Russian Assault Rifles The best maritime General director technologies Editor-in-chief 10 ‘Smart’ Target for Trainin Valeriy STOLNIKOV 10th International Maritime Defence Show – IMDS-2021, which is held from 23 to 27 June Chief editor’s deputy 2021 in St. Petersburg under the Russian Govern- Elena SOKOLOVA MAIN TOPICS ment decree № 1906-r of 19.07.2019, is defi- Commercial director 12 Military Technical nitely unique. Show is gathering in obviously the Oleg DEINEKO best innovations for Navy and different maritime Cooperation technologies for any tasks. -

Turkey's S-400 Dilemma

EDAM Foreign Policy and Security Paper Series 2017/5 Turkey’s S-400 Dilemma July, 2017 Dr. Can Kasapoglu Defense Analyst, EDAM 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • This report’s core military assessment of a possible • In fact, modern air defense concepts vary between S-400 deal concludes that Ankara’s immediate aim is fighter aircraft-dominant postures, SAM-dominant to procure the system primarily for air defense missi- postures, and balanced force structures. However, if ons as a surface-to-air missile (SAM) asset, rather than Ankara is to replace its fighter aircraft-dominant con- performing ballistic missile defense (BMD) functions. cept with a SAM and aircraft mixed understanding, This priority largely stems from the Turkish Air Force’s which could be an effective alternative indeed, then currently low pilot-to-cockpit ratio (0.8:1 by open- it has to maintain utmost interoperability within its source 2016 estimates). Thus, even if the procurement principal arsenal. Key importance of interoperability is to be realized, Turkey will first and foremost operate between aircraft and integrated air and missile defense the S-400s as a stopgap measure to augment its air systems can be better understood by examining the superiority calculus over geo-strategically crucial areas. Israeli Air Force’s (IAF) recent encounter in the Syrian This is why the delivery time remains a key condition. airspace. On March 17, 2017, a Syrian S-200 (SA-5) battery fired an anti-aircraft missile to hunt down an • Although it is not a combat-tested system, not only IAF fixed-wing aircraft (probably an F-15 or F-16 Russian sources but also many Western military variant). -

Russian Military Developments and Strategic Implications

i [H.A.S.C. No. 113–105] RUSSIAN MILITARY DEVELOPMENTS AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD APRIL 8, 2014 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–450 WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, http://bookstore.gpo.gov. For more information, contact the GPO Customer Contact Center, U.S. Government Printing Office. Phone 202–512–1800, or 866–512–1800 (toll-free). E-mail, [email protected]. COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California, Chairman MAC THORNBERRY, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina LORETTA SANCHEZ, California J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina JEFF MILLER, Florida ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania JOE WILSON, South Carolina SUSAN A. DAVIS, California FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island ROB BISHOP, Utah RICK LARSEN, Washington MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio JIM COOPER, Tennessee JOHN KLINE, Minnesota MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JOE COURTNEY, Connecticut TRENT FRANKS, Arizona DAVID LOEBSACK, Iowa BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas JOHN GARAMENDI, California DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia ROBERT J. WITTMAN, Virginia COLLEEN W. HANABUSA, Hawaii DUNCAN HUNTER, California JACKIE SPEIER, California JOHN FLEMING, Louisiana RON BARBER, Arizona MIKE COFFMAN, Colorado ANDRE´ CARSON, Indiana E. SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia CAROL SHEA-PORTER, New Hampshire CHRISTOPHER P. GIBSON, New York DANIEL B. MAFFEI, New York VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri DEREK KILMER, Washington JOSEPH J. HECK, Nevada JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JON RUNYAN, New Jersey TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia SCOTT H. -

US Sanctions on Russia

U.S. Sanctions on Russia Updated January 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45415 SUMMARY R45415 U.S. Sanctions on Russia January 17, 2020 Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian Specialist in European aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russia in Affairs response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Most Members of Congress support a robust Kristin Archick Specialist in European use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions. Affairs Sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Rebecca M. Nelson Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Specialist in International Ukraine: the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Trade and Finance Ukraine Act of 2014 (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859). Dianne E. Rennack Specialist in Foreign Policy In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Countering Russian Influence Legislation in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. -

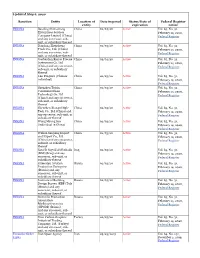

Sanction Entity Location of Date Imposed Status/Date of Federal Register Entity Expiration Notice INKSNA Baoding Shimaotong China 02/03/20 Active Vol

Updated May 6, 2020 Sanction Entity Location of Date imposed Status/Date of Federal Register entity expiration notice INKSNA Baoding Shimaotong China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Enterprises Services February 14, 2020, Company Limited (China) Federal Register and any successor, sub- unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Dandong Zhensheng China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Trade Co., Ltd. (China) February 14, 2020, and any successor, sub- Federal Register unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Gaobeidian Kaituo Precise China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Instrument Co. Ltd February 14, 2020, (China) and any successor, Federal Register sub-unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Luo Dingwen (Chinese China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, individual) February 14, 2020, Federal Register INKSNA Shenzhen Tojoin China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Communications February 14, 2020, Technology Co. Ltd Federal Register (China) and any successor, sub-unit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Shenzhen Xiangu High- China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, Tech Co., Ltd (China) and February 14, 2020, any successor, sub-unit, or Federal Register subsidiary thereof INKSNA Wong Myong Son China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, (individual in China) February 14, 2020, Federal Register INKSNA Wuhan Sanjiang Import China 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, and Export Co., Ltd February 14, 2020, (China) and any successor, Federal Register subunit, or subsidiary thereof INKSNA Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada Iraq 02/03/20 Active Vol. 85, No. 31, (KSS) (Iraq) and any February 14, 2020, successor, sub-unit, or Federal Register subsidiary thereof INKSNA Kumertau Aviation Russia 02/03/20 Active Vol. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 193/Wednesday, October 5, 2016

69190 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 193 / Wednesday, October 5, 2016 / Notices system. The MTSNAC will consider congestion and increase mobility Authority: 49 CFR part 1.93(a); 5 U.S.C. new bylaws, form subcommittees and throughout the domestic transportation 552b; 41 CFR parts 102–3; 5 U.S.C. app. working groups, and develop work system; Sections 1–16 plans and recommendations. e. actions designed to strengthen By Order of the Maritime Administrator. DATES: The meeting will be held on maritime capabilities essential to Dated: September 29, 2016. Tuesday, October 18, 2016 from 8:00 economic and national security; T. Mitchell Hudson, Jr., f. ways to modernize the maritime a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and Wednesday, Secretary, Maritime Administration. October 19, 2016 from 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 workforce and inspire and educate the next generation of mariners; [FR Doc. 2016–23989 Filed 10–4–16; 8:45 am] p.m. Eastern Daylight Saving Time BILLING CODE 4910–81–P (EDT). g. actions designed to encourage the continued development of maritime ADDRESSES: The meeting will be held at innovation and; the St. Louis City Center Hotel, 400 h. any other actions MARAD could South 14th Street, St. Louis, MO 63103. take to meet its mission to foster, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Eric promote, and develop the maritime Office of Foreign Assets Control Shen, Co-Designated Federal Officer at: industry of the United States. (202) 308–8968, or Capt. Jeffrey Public Participation Sanctions Actions Pursuant to Flumignan, Co-Designated Federal Executive Orders 13660, 13661, 13662, The meeting will be open to the Official at (212) 668–2064 or via email: and 13685 [email protected] or visit the MTSNAC public. -

OFFICE of FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES to the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2015 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign center/sanctions/Programs/Pages/ukraine.aspx# Order 13662 Directive Determination - Subject to Assets Control ("OFAC") is a reference tool directives. [UKRAINE-EO13662] (Linked To: Directive 2; alt. Executive Order 13662 Directive providing actual notice of actions by OFAC with OPEN JOINT-STOCK COMPANY ROSNEFT Determination - Subject to Directive 4; For more respect to persons that are identified pursuant to OIL COMPANY). information on directives, please visit the Executive Order 13662 and are listed on the AKTSIONERNOE OBSHCHESTVO following link: http://www.treasury.gov/resource- Sectoral Sanctions I dentifications List (SSI List). KOMMERCHESKI BANK GLOBEKS (f.k.a. center/sanctions/Programs/Pages/ukraine.aspx# The latest changes may appear here prior to their CJSC GLOBEXBANK; a.k.a. GLOBEKSBANK, directives. [UKRAINE-EO13662] (Linked To: publication in the Federal Register, and it is AO; a.k.a. GLOBEX COMMERCIAL BANK, OPEN JOINT-STOCK COMPANY ROSNEFT intended that users rely on changes indicated in JOINT STOCK COMPANY; a.k.a. OIL COMPANY). this document. Such changes reflect official GLOBEXBANK; f.k.a. ZAKRYTOE BANK BELVEB OJSC (a.k.a. actions of OFAC, and will be ref lected as soon as AKTSIONERNOE OBSHCHESTVO BELVESHECONOMBANK OAO; a.k.a. practicable in the Federal Register under the KOMMERCHESKI BANK GLOBEKS), d. 59 str. BELVNESHECONOMBANK OPEN JOINT index heading "Foreign Assets Control." New 2 ul. Zemlyanoi Val, Moscow 109004, Russia; STOCK COMPANY), 29 Pobeditelei ave., Minsk Federal Register notices with regard to SWIFT/BIC GLOB RU MM; Website 220004, Belarus; SWIFT/BIC BELB BY 2X; identifications made under Executive Order 13662 globexbank.ru; Executive Order 13662 Directive Website bveb.by; Executive Order 13662 may be published at any time. -

Tax Evasion and Weapon Production Mailbox Arms Companies in the Netherlands

Issue Brief – May 2016 Tax evasion and weapon production Mailbox arms companies in the Netherlands Martin Broek Stop Wapenhandel www.stopwapenhandel.org Tax evasion and weapon production | 1 AUTHOR: Martin Broek EDITORS: Nick Buxton and Wendela de Vries DESIGN: Evan Clayburg Published by Transnational Institute – www.TNI.org and Stop Wapenhandel – www.StopWapenhandel.org Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is properly cited. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy or link of the text in which this document is used or cited. Please note that for some images the copyright may lie elsewhere and copyright conditions of those images should be based on the copyright terms of the original source. http://www.tni.org/copyright ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This is an updated briefing, initially released in January 2016. Tax evasion and weapon production | 2 Contents Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Short history of Dutch tax law 6 Chapter 2: Tax evasion in the Netherlands 8 Chapter 3: Top 10 defence industries and Dutch holdings 11 Chapter 4: Tax evasion by company 14 Chapter 5: Corruption and misbehaviour 27 Chapter 6: The Dutch connection in the Malaysian airline disaster 29 Chapter 7: Panama Papers and the arms trade 32 Conclusion 35 Annex – The use of Trusts 36 Notes 37 Tax evasion and weapon production | 3 Introduction The revelations of the leaked Panama Papers in April 2016 pushed the issue of tax and tax evasion high up the international political agenda. Prompting scandals and high profile resignations, the 11.5 million documents from the offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca unveiled some of the tricks and strategies that countless politicians, businessmen and elites use to avoid taxes. -

How the Sale of Mistral Warships to Russia Is Undermining EU Arms Transfer Controls Acknowledgements

BRIEFING · NOVEMBER 2014 An ill wind How the sale of Mistral warships to Russia is undermining EU arms transfer controls Acknowledgements This briefing was written by Roy Isbister of Saferworld and Yannick Quéau of GRIP. The authors wish to thank Daniel Bertoli of Saferworld for his extensive research support. This briefing was made possible by the generous support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. © GRIP and Saferworld, November 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without full attribution. GRIP and Saferworld welcome and encourage the utilisation and dissemination of the material included in this publication. i Executive summary In 2011 France agreed a contract to supply Russia with two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships with an option for two more to follow. This was the first major arms sale to Russia by a North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) state. Controversial at the time it was agreed, the recent deterioration in relations with Russia because of the Ukrainian crisis has returned the Mistral sale to the spotlight, with forthright opposition to the deal from around the European Union (EU). Until recently France has appeared determined to proceed, apparently for economic reasons and because of fears that, if it were to cancel, this would damage its reputation as a ‘reliable supplier’ of military equipment. Even an EU arms embargo on Russia, introduced on 31 July 2014, failed to prevent the sale as it does not apply to pre-existing deals. -

Ideas for Peace and Security

The Arms Trade Treat and Russian Arms Exports: Expectations and Possible Consequences S Sergey Denisentsev Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Konstantin Makienko Deputy Director of the Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Translated by Ivan Khokhotva Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies (CAST) is a Russian non- governmental research center specializing in the study of Russia’s military- technical cooperation with foreign states, the restructuring of Russia’s defense industry and defense procurement. This work was commissioned by the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), in the context of its project “supporting the Arms Trade Treaty Negotiations through Regional Discussions and Expertise Sharing”. Reprinted with the permission from UNIDIR. The views herein do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the United Nations, UNIDIR, or its sponsors. Introduction RESOURCE The adoption of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) would undoubtedly affect all the leading arms exporters and importers, including Russia, which is the world’s second-biggest arms exporter. This study aims to assess the possible effects of the Arms Trade Treaty, if and when it is adopted, on Russian arms exports. To that end we are going to review the current state of these exports; look at the R distinctive features of the Russian arms export control system; and speak to representatives of the Russian government, leading Russian defense companies, and international relations experts about their expectations from the ATT. 1. Russian arms exports in 2002-2011. Export control system: current state, outlook and transparency. 1.1 Russian arms export control system Arms exports – which fall under the Russian definition of “military and technical cooperation”, along with imports – are very important for the Russian economy. -

Ukraine-/Russia-Related Designations An...Ublication of New Faqs And

4/7/2018 Resource Center Home » Resource Center » Financial Sanctions » OFAC Recent Actions » Ukraine/Russiarelated Designations and Identification Update; Syria Designations; Kingpin Act Designations; Issuance of Ukraine/Russiarelated General Licenses 12 and 13; Publication of New FAQs and Updated FAQ Ukraine/Russiarelated Designations and Identification Update; Syria Designations; Kingpin Act Designations; Issuance of Ukraine/Russiarelated General Licenses 12 and 13; Publication of New FAQs and Updated FAQ 4/6/2018 Today, the Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is designating certain persons pursuant to the Ukraine/Russiarelated authorities and two persons pursuant to the Government of Syria authorities (see below). In addition, OFAC is issuing the following two Ukraine/Russiarelated general licenses in connection with these designations: General License 12 “Authorizing Certain Activities Necessary to Maintenance or Wind down of Operations or Existing Contracts”; General License 13 “Authorizing Certain Transactions Necessary to Divest or Transfer Debt, Equity, or other Holdings in Certain Blocked Persons”. OFAC is also publishing eight new FAQsrelating to today’s action and publishing one updated FAQ related to the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) . In addition, OFAC has added the following names to its SDN List. OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL Specially Designated Nationals List Update The following individuals have been added to OFAC's SDN List: AKIMOV, Andrey Igorevich, Russia; DOB 1953; POB Leningrad, Russia; Gender Male; Chairman of the Management Board of Gazprombank (individual) [UKRAINEEO13661]. BOGDANOV, Vladimir Leonidovich, Russia; DOB 28 May 1951; POB Suyerka, Uporovsky District, Tyumen Region, Russian Federation; Gender Male (individual) [UKRAINEEO13662].