Disney: Castles, Kingdoms and (No) Common Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Wagner's Stunt Resume

Mark Aaron Wagner HEIGHT: 5’10” Weight: 165 lbs. Stuntman / Stunt Coordinator/ Actor S.A.G./ A.F.T.R.A./ U.B.C.P./ A.C.T.R.A Suit- 38-40R, Shirt- 16x34 International Stunt Association- 818-501-5225 Waist- 32, Inseem- 31 KMR (agent)- (818) 755-7534 Shoe: 10 www.MarkAaronWagner.com (Online Demo) Current Resume on IMDB.com Feature Films (Full List Upon Request) Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Zoë Bell/ Rob Alonzo Captain Marvel (driver) Hank Amos/ Jeff Habberstad Ant-Man and The Wasp (dbl. Paul Rudd) Brycen Counts Peppermint (stunt dbl.) Keith Woulard Deadpool 2 (driver) Owen Walstrom/ Darrin Prescott Bright Rob Alonzo Predator Marny Eng/ Lance Gilbert Captain America: Civil War (dbl.- Paul Rudd) Sam Hargrave/ Doug Coleman Three Billboards (dbl.- Sam Rockwell) Doug Coleman PeeWee’s Big Holiday (dbl.- Paul Reubens) Mark Rayner Maze Runner: Scorch Trials ND George Cottle Ant-Man (dbl.- Paul Rudd) Jeff Habberstad Stretch (dbl.- Patrick Wilson) Ben Bray Captain America: Winter Soldier Strike Agent Tom Harper/ Casey O’Neil 300: Rise of an Empire Artemisia Father Damon Caro Iron Man 3 Extremis Soldier Markos Rounthwaite/ Mike Justus/ Jeff Habberstad Secret Life of Walter Mitty (dbl.- Adam Scott) Tim Trella/ Clay Cullen Dark Knight Rises ND/ Driving Tom Struthers/ George Cottle Gangster Squad (dbl.-Frank Grillo) Doug Coleman Men in Black 3 ND Wade Eastwood/ Simon Crane X-Men: First Class MIB Jeff Habberstad/ Brian Smrz Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Drving Jeff Habberstad This Is 40 (dbl.- Paul Rudd) Joel Kramer The Master (dbl.- Joaquin Phoenix) Garrett -

The “Tron: Legacy”

Release Date: December 16 Rating: TBC Run time: TBC rom Walt Disney Pictures comes “TRON: Legacy,” a high-tech adventure set in a digital world that is unlike anything ever captured on the big screen. Directed by F Joseph Kosinski, “TRON: Legacy” stars Jeff Bridges, Garrett Hedlund, Olivia Wilde, Bruce Boxleitner, James Frain, Beau Garrett and Michael Sheen and is produced by Sean Bailey, Jeffrey Silver and Steven Lisberger, with Donald Kushner serving as executive producer, and Justin Springer and Steve Gaub co-producing. The “TRON: Legacy” screenplay was written by Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz; story by Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz and Brian Klugman & Lee Sternthal; based on characters created by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird. Presented in Disney Digital 3D™, Real D 3D and IMAX® 3D and scored by Grammy® Award–winning electronic music duo Daft Punk, “TRON: Legacy” features cutting-edge, state-of-the-art technology, effects and set design that bring to life an epic adventure coursing across a digital grid that is as fascinating and wondrous as it is beyond imagination. At the epicenter of the adventure is a father-son story that resonates as much on the Grid as it does in the real world: Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund), a rebellious 27-year-old, is haunted by the mysterious disappearance of his father, Kevin Flynn (Oscar® and Golden Globe® winner Jeff Bridges), a man once known as the world’s leading tech visionary. When Sam investigates a strange signal sent from the old Flynn’s Arcade—a signal that could only come from his father—he finds himself pulled into a digital grid where Kevin has been trapped for 20 years. -

Famous Cartoon Characters and Creators

Famous Cartoon Characters and Creators Sr No. Cartoon Character Creator 1 Archie,Jughead (Archie's Comics) John L. Goldwater, Vic Bloom and Bob Montana 2 Asterix René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo 3 Batman Bob Kane 4 Beavis and Butt-Head Mike Judge 5 Betty Boop Max Flasher 6 Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Porky Pig Tex Avery 7 Calvin and Hobbes Bill Watterson 8 Captain Planet and the Planeteers Ted Turner, Robert Larkin III, and Barbara Pyle 9 Casper Seymour Reit and Joe Oriolo 10 Chacha Chaudhary Pran Kumar Sharma 11 Charlie Brown Charles M. Schulz 12 Chip 'n' Dale Bill Justice 13 Chhota Bheem Rajiv Chilaka 14 Chipmunks Ross Bagdasarian 15 Darkwing Duck Tad Stones 16 Dennis the Menace Hank Ketcham 17 Dexter and Dee Dee (Dexter's Laboratory) Genndy Tartakovsky 18 Doraemon Fujiko A. Fujio 19 Ed, Edd 'n' Eddy Danny Antonucci 20 Eric Cartman (South Park) Trey Parker and Matt Stone 21 Family Guy Seth MacFarlane Fantastic Four,Hulk,Iron Man,Spider-Man,Thor,X- 22 Stan Lee Men and Daredevil 23 Fat Albert Bill Cosby,Ken Mundie 24 Garfield James Robert "Jim" Davis 25 Goofy Art Babbitt 26 Hello Kitty Yuko Shimizu 27 Inspector gadget Jean Chalopin, Bruno Bianchi and Andy Heyward 28 Jonny Quest Doug Wildey 29 Johnny Bravo Van Partible 30 Kermit Jim Henson Marvin Martian, Pepé Le Pew, Wile E. Coyote and 31 Chuck Jones Road Runner 32 Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Pluto Walt Disney 33 Mowgli Rudyard Kipling 34 Ninja Hattori-kun Motoo Abiko 35 Phineas and Ferb Dan Povenmire and Jeff “Swampy” Marsh 36 Pinky and The Brain Tom Ruegger 37 Popeye Elsie Segar 38 Pokémon Satoshi Tajiri 39 Ren and Stimpy John Kricfalusi 40 Richie Rich Alfred Harvey and Warren Kremer Page 1 of 2 Sr No. -

Mining the Box: Adaptation, Nostalgia and Generation X

From TV to Film How to Cite: Hill, L 2018 Mining the Box: Adaptation, Nostalgia and Generation X. Open Library of Humanities, 4(1): 1, pp. 1–28, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.99 Published: 09 January 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Library of Humanities, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2017 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. Lisa Hill, ‘Mining the Box: Adaptation, Nostalgia and Generation X’, (2018) 4(1): 1 Open Library of Humanities, DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/olh.99 FROM TV TO FILM Mining the Box: Adaptation, Nostalgia and Generation X Lisa Hill University of the Sunshine Coast, AU [email protected] This article identifies the television to film phenomenon by cataloguing contemporary films adapted from popular television shows of the 1960s and 1970s. This trend is located within the context of Generation X and considered within the framework of nostalgia and Linda Hutcheon’s (2006) conception of adaptation. The history of re-visiting existing texts in screen culture is explored, and the distinction between remakes and adaptation is determined. -

NYT Crossword

Amanda Rafkin and Ross Trudeau Wednesday, March 24, 2021 Edited by Will Shortz ACROSS 57 ___ card, part of a 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 wedding invitation Catch 13 14 15 16 4 Onetime Volvo 60 On a magnet competitors they're called 17 18 19 9 Title character of poles 20 21 22 23 a John Irving 61 *Inspector Gadget novel or McGruff the 24 25 26 13 "Is that ___?" Crime Dog? 14 Alternatives to 64 Happening now 27 28 29 65 More slick windows? 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 16 Diva's delivery 66 Big ___ (praise, 17 *Donald Duck or slangily) 38 39 40 41 Popeye? 67 Duchamp's art 42 43 44 19 One of Jacob's 12 movement sons 68 Monopoly stack 45 46 47 48 49 20 Writing sister of 69 Bear in a 2012 Charlotte and comedy 50 51 52 53 54 DOWN Emily 55 56 57 58 59 21 What doesn't go a 1 Org. with long. way? Perseverance 60 61 62 63 22 Ready to roll 2 ___ Kim, 64 65 66 24 *Minions or 7-year-old star of Mario? the Golden 67 68 69 27 Hand down Globe-winning 29 "Goodness "Minari" 28 Tennis great 46 Manipulate the gracious!" 3 Driver's danger posthumously outcome of 30 Danger for 4 ___ Paulo awarded the 47 Scrap Indiana Jones 5 Runway model? Presidential 49 Podcaster Maron 31 Pick up 6 Silk center of Medal of Freedom 50 Sphere 34 Locale of the India 32 Classic name in 51 "Labor ___ vincit" annual Nobel 7 Comic strip children's (Oklahoma's state Peace Prize antagonist with literature motto) ceremony massive arms 33 Home to the 52 Available for 38 Question asked 8 Tre x due Christ the home viewing, in regarding two 9 Wonder-ful Redeemer statue, a way red-carpet photos actress? in brief 53 "Rolling in the of those named in 10 Spinning 35 Worry to Deep" hitmaker the starred clues? 11 Compete with exhaustion 54 Title girl with a 42 First name among 12 Figure skating 36 Luau loops gun in an late-night TV category 37 Subject of the Aerosmith hit hosts 15 Writer Larsson 2013 58 Use a Juul, say 43 "Boo-hoo" 18 Wine dregs documentary 59 Affliction for many 44 Wrestler Flair 23 Grp. -

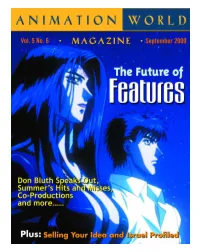

Cartoons Gerard Raiti Looks Into Why Some Cartoons Make Successful Live-Action Features While Others Don’T

Table of Contents SEPTEMBER 2000 VOL.5 NO.6 4 Editor’s Notebook A success and a failure? 6 Letters: [email protected] FEATURE FILMS 8 A Conversation With The New Don Bluth After Titan A.E.’s quick demise at the box office and the even quicker demise of Fox’s state-of-the-art animation studio in Phoenix, Larry Lauria speaks with Don Bluth on his future and that of animation’s. 13 Summer’s Sleepers and Keepers Martin “Dr. Toon” Goodman analyzes the summer’s animated releases and relays what we can all learn from their successes and failures. 17 Anime Theatrical Features With the success of such features as Pokemon, are beleaguered U.S. majors going to look for 2000 more Japanese imports? Fred Patten explains the pros and cons by giving a glimpse inside the Japanese film scene. 21 Just the Right Amount of Cheese:The Secrets to Good Live-Action Adaptations of Cartoons Gerard Raiti looks into why some cartoons make successful live-action features while others don’t. Academy Award-winning producer Bruce Cohen helps out. 25 Indie Animated Features:Are They Possible? Amid Amidi discovers the world of producing theatrical-length animation without major studio backing and ponders if the positives outweigh the negatives… Education and Training 29 Pitching Perfect:A Word From Development Everyone knows a great pitch starts with a great series concept, but in addition to that what do executives like to see? Five top executives from major networks give us an idea of what makes them sit up and take notice… 34 Drawing Attention — How to Get Your Work Noticed Janet Ginsburg reveals the subtle timing of when an agent is needed and when an agent might hinder getting that job. -

A Data Programming-Based Labeling System for Industrial Images

Inspector Gadget: A Data Programming-based Labeling System for Industrial Images Geon Heo, Yuji Roh, Seonghyeon Hwang, Dayun Lee, Steven Euijong Whang Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology Daejeon, Republic of Korea {geon.heo,yuji.roh,sh.hwang,dayun.lee,swhang}@kaist.ac.kr ABSTRACT Inspector As machine learning for images becomes democratized in the Soft- Gadget ware 2.0 era, one of the serious bottlenecks is securing enough Weak OK labeled data for training. This problem is especially critical in a Labels manufacturing setting where smart factories rely on machine learn- Smart End Model ing for product quality control by analyzing industrial images. Such Factory images are typically large and may only need to be partially ana- Defect lyzed where only a small portion is problematic (e.g., identifying Unlabeled defects on a surface). Since manual labeling these images is expen- Figure 1: Labeling industrial images with Inspector Gadget sive, weak supervision is an attractive alternative where the idea is in a smart factory application. to generate weak labels that are not perfect, but can be produced at scale. Data programming is a recent paradigm in this category where it uses human knowledge in the form of labeling functions product images [27]. In medical applications, MRI scans are ana- and combines them into a generative model. Data programming has lyzed to identify diseases like cancer [23]. However, many compa- been successful in applications based on text or structured data and nies are still reluctant to adapt machine learning due to the lack of can also be applied to images usually if one can fnd a way to con- labeled data where manual labeling is simply too expensive [38]. -

Feature Films and Licensing & Merchandising

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 88 NovemberNovember 1998 1998 Feature Films and Licensing & Merchandising A Bug’s Life John Lasseter’s Animated Life Iron Giant Innovations The Fox and the Hound Italy’s Lanterna Magica Pro-Social Programming Plus: MIPCOM, Ottawa and Cartoon Forum TABLE OF CONTENTS NOVEMBER 1998 VOL.3 NO.8 Table of Contents November 1998 Vol. 3, No. 8 4 Editor’s Notebook Disney, Disney, Disney... 5 Letters: [email protected] 7 Dig This! Millions of Disney Videos! Feature Films 9 Toon Story: John Lasseter’s Animated Life Just how does one become an animation pioneer? Mike Lyons profiles the man of the hour, John Las- seter, on the eve of Pixar’s Toy Story follow-up, A Bug’s Life. 12 Disney’s The Fox and The Hound:The Coming of the Next Generation Tom Sito discusses the turmoil at Disney Feature Animation around the time The Fox and the Hound was made, marking the transition between the Old Men of the Classic Era and the newcomers of today’s ani- 1998 mation industry. 16 Lanterna Magica:The Story of a Seagull and a Studio Who Learnt To Fly Helming the Italian animation Renaissance, Lanterna Magica and director Enzo D’Alò are putting the fin- ishing touches on their next feature film, Lucky and Zorba. Chiara Magri takes us there. 20 Director and After Effects: Storyboarding Innovations on The Iron Giant Brad Bird, director of Warner Bros. Feature Animation’s The Iron Giant, discusses the latest in storyboard- ing techniques and how he applied them to the film. -

Inspector Gadget: a Data Programming-Based Labeling System for Industrial Images

Inspector Gadget: A Data Programming-based Labeling System for Industrial Images Geon Heo, Yuji Roh, Seonghyeon Hwang, Dayun Lee, Steven Euijong Whang Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology Daejeon, Republic of Korea {geon.heo,yuji.roh,sh.hwang,dayun.lee,swhang}@kaist.ac.kr ABSTRACT Inspector As machine learning for images becomes democratized in the Soft- Gadget Weak ware 2.0 era, one of the serious bottlenecks is securing enough OK labeled data for training. This problem is especially critical in a Labels manufacturing setting where smart factories rely on machine learn- Smart End Model ing for product quality control by analyzing industrial images. Such Factory images are typically large and may only need to be partially ana- Unlabeled Defect lyzed where only a small portion is problematic (e.g., identifying defects on a surface). Since manual labeling these images is expen- Figure 1: Labeling industrial images with Inspector Gadget sive, weak supervision is an attractive alternative where the idea is in a smart factory application. to generate weak labels that are not perfect, but can be produced at scale. Data programming is a recent paradigm in this category where it uses human knowledge in the form of labeling functions A conventional solution is to collect enough labels manually and combines them into a generative model. Data programming has and train say a convolutional neural network on the training data. been successful in applications based on text or structured data and However, fully relying on crowdsourcing for image labeling can can also be applied to images usually if one can find a way to con- be too expensive. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Chad Parker Stuntman / Actor / SAG

Chad Parker Stuntman / Actor / SAG Height: 5'6" Hair: Brown / Bald / Shaved Missy's: 818-774-3889 Weight: 150 Ibs. Eyes: Brown Direct: 818-416-4580 Specialties: Black Belt Tae Kwon Do, Rick Seaman's. Stunt Driving, Trampoline, High Falls, Motor Cycles Film Doubles Stunt Coor. Live Free Die Hard Stunt ObI. John Branagan Domino Mafia Thug Chuck Picerni Jr. Haunted Mansion Stunt ObI. Wallace Shawn Doug Coleman Invasion Stunt ObI. John Branagan Looney Tunes Back In Action Stunt ObI. Robert Picardo Gary Combs Minority Report NO Stunts Brian Smrz Wind Talkers NO Stunts Brian Smrz The Anima/ Precision Driving Greg Smrz Austin Powers 2 Stunt ObI. Dr. Evil Bud Davis Inspector Gadget Actor / Car Thief Brian Smrz Bowfinger Ninja Bud Davis Suburbans Actor / Stunts Terry James My Favorite Martian Stunt ObI. Wallace Shawn Ernie Orsatti Axe Actor / Dirt bikes Kim Kosky Television Desperate House Wives (3 episodes) Stunt ObI. Bob Newhart Wally Crowder My Name Is Eorl (2 episodes) Stunt ObI. Dragnet Homeless man Ben Scott Charmed (5 episodes) Stunt ObI. Armin Shimmerman Noon Orsatti Yes Dear Stunt ObI. Patrick McCarthy AI Jones The Invisible Man (season regular) Stunt ObI. Paul Ben Victor Gary Baxley The Practice Stunt ObI. Jason Kravits Ernie Orsatti V.I.P. NO Stunts Jeff Cadiente The Fugitive Utility Stunts (rigging) Kerry Rossall Resurrection Boulevard Stunt ObI. Lawrence Monoson Jimmy Nickerson Son of the Beach Actor / Water Work Denny Pierce The Tick Russian Soldier Brian Smrz Martial Law (3 episodes) NO Stunts Jeff Cadiente Buffy the Vampire Slayer (3 episodes) Vampire Jeff Pruett V. I. -

Extension . Ucsd

WE DON’T GIVE 10/10 PAGE TO EVERYTHING. 8 VOLUME XLIII, ISSUE XVI THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2010 WWW.UCSDGUARDIAN.ORG UCÊStudentsÊ AÊCLOSERÊLOOK ArrestedÊatÊ BEFORE THE PublicationsÊ UCSFÊRegentsÊ ReactÊtoÊNewÊ FINAL BATTLE MediaÊFundingÊ Meeting ANGST OVERSHADOWS ACTION IN THE PENULTIMATE FILM OF THE BELOVED “POTTER” SERIES. BY ARIELLE SALLAI * HIATUS EDITOR By Nisha Kurani Guidelines A N E FILMREVIEW By Justin Kauker Eleven UC students were arrested and S W four police officers were injured yesterday when a rally at the UC Board of Regents Council allocated $4,700 to 11 media meeting held at UC San Francisco turned orgs for Winter Quarter at its meeting last violent. night, following funding guidelines passed Approximately 200 students and 100 UC on Nov. 3. The new guidelines place a quar- workers gathered in front of a UCSF hall terly funding cap of $450 on existing media where the Regents were meeting to protest orgs and $200 for new orgs. UC President Mark G. Yudof’s proposed Following the recommendation of 8-percent fee increase. The Regents will Associate Vice President of Student Orgs vote on the increase today. Carli Thomas and Vice President of Finance About 15 of those students and Resources Andrew Ang, council allo- OPINION were pepper sprayed during cated the maximum $450 to 10 media orgs It’s hard their attempts to break though and $200 to the new media org Robot not to feel the barricades and into the ▶ HIATUS Report. defeated at meeting, according to Los Thomas said she is working on creating this point. funding caps for all student organizations.