Reggie Brown Injury Timeline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rocket Fiber's Launch Includes Second Stage

20150302-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 2/27/2015 5:29 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 31, No. 9 MARCH 2 – 8, 2015 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2015 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Page 3 ROCKET FIBER:PHASE 1 COVERAGE AREA Panasonic unit plays ‘Taps’ ‘To chase for apps, rethinks strategy According to figures provided by Rocket the animal’ Fiber, the download times for ... “Star Wars” movie on Blu-ray: about seven hours at a typical residential Internet speed of Packard Plant owner eyes bids 10 megabits per second but about 4½ minutes at gigabit speed. for historic downtown buildings An album on iTunes: About one minute on LOOKING BACK: ’80s office residential Internet and less than a second BY KIRK PINHO at gigabit speed boom still rumbles in ’burbs CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS Over breakfast at the Inn on Ferry Street in Lions invite Midtown, Fernando Palazuelo slides salt and fans to pepper shakers across the table like chess pieces. They are a representation of his Detroit take a hike real estate strategy. Yes, he says, he’s getting at new Rocket Fiber’s launch ready to make a series of big moves. The new owner of the 3.5 million-square-foot fantasy football camp Packard Plant on the city’s east side has much broader ambitions for his portfolio in the city, which first took notice of him in 2013 when he Retirement Communities bought the shuttered plant — all 47 buildings, all 40 acres — for a mere $405,000 at a Wayne includes second stage County tax foreclosure auction. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

Ball State Vs Clemson (9/5/1992)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1992 Ball State vs Clemson (9/5/1992) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Ball State vs Clemson (9/5/1992)" (1992). Football Programs. 217. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/217 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. $3.00 Clemson fi% Ball State Memorial Stadium September 5, 1992 TEMAFA - Equipmentforfiber reclamation. DORNIER - TJie Universal weaving machine. Air jet and VOUK - Draw Frames, Combers, tappers, Automatic rigid rapier. Transport systems. SOHLER - Traveling blowing and vacuuming systems. DREF 2 AND DREF 3 - Friction spinning system. GENKINGER - Material handling systems. FEHRER - NL 3000: Needling capabilities up to 3000 - inspection systems. strokes per minute. ALEXANDER Offloom take-ups and HACOBA - Complete line of warping and beaming LEMAIRE - Warp transfer andfabric transfer printing. machinery. FONGS - Equipmentfor piece and package dyeing. KNOTEX- Will tie all yarns. -

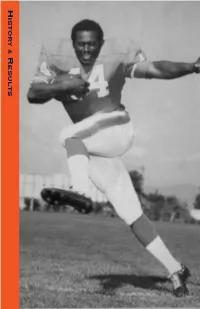

History and Results

H DENVER BRONCOS ISTORY Miscellaneous & R ESULTS Year-by-Year Stats Postseason Records Honors History/Results 252 Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season DENVER BRONCOS BRONCOS ALL-TIME DRAFT CHOICES NUMBER OF DRAFT CHOICES PER SCHOOL 20 — Florida 15 — Colorado, Georgia 14 — Miami (Fla.), Nebraska 13 — Louisiana State, Houston, Southern California 12 — Michigan State, Washington 11 — Arkansas, Arizona State, Michigan 10 — Iowa, Notre Dame, Ohio State, Oregon 9 — Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Purdue, Virginia Tech 8 — Arizona, Clemson, Georgia Tech, Minnesota, Syracuse, Texas, Utah State, Washington State 7 — Baylor, Boise State, Boston College, Kansas, North Carolina, Penn State. 6 — Alabama, Auburn, Brigham Young, California, Florida A&M, Northwestern, Oklahoma State, San Diego, Tennessee, Texas A&M, UCLA, Utah, Virginia 5 — Alcorn State, Colorado State, Florida State, Grambling, Illinois, Mississippi State, Pittsburgh, San Jose State, Texas Christian, Tulane, Wisconsin 4 — Arkansas State, Bowling Green/Bowling Green State, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa State, Jackson State, Kansas State, Kentucky, Louisville, Maryland-Eastern Shore, Miami (Ohio), Missouri, Northern Arizona, Oregon State, Pacific, South Carolina, Southern, Stanford, Texas A&I/Texas A&M Kingsville, Texas Tech, Tulsa, Wyoming 3 — Detroit, Duke, Fresno State, Montana State, North Carolina State, North Texas State, Rice, Richmond, Tennessee State, Texas-El Paso, Toledo, Wake Forest, Weber State 2 — Alabama A&M, Bakersfield -

Head Coach Sylvester Croom (PDF).Pdf

8 hen Mississippi State began its search in October 2003 for the 31st head coach in its long football history, the university sought an enthusiastic teacher with the energy to rebuild the Bulldog football program and an individual with an attention to detail who demands the Wdiscipline needed to bring structure to a vast organi- zation. On all accounts, MSU found its man when it hired Sylvester Croom on Dec. 1, 2003. “Sylvester Croom met all of the criteria we laid forth for the selection of a new head football coach at Mississippi State,” Director of Athletics Larry Templeton said. “We went after the best football coach, and we’re confident we found that individual in Sylvester Croom.” Since his hiring, Croom has undertaken the daunting task of constructing the foundation upon which the Bulldog football program will be rebuilt. There is little question that progress toward that goal has been achieved. In the three years since being named to head MSU’s football fortunes, the traits that made Croom the best coach for State have come to life. Croom became an in-demand speaker at alumni and booster events because of his forthright approach to directing the pigskin program. But his non-stop energy on the banquet circuit was only exceeded by the fervor with which he began shaping the Bulldog football operation. He estab- lished new offensive and defensive systems, paying particular attention to an attack which mirrored what he taught as a National Football League assistant. And despite the fact he had been away from the college game for 17 years as a pro coach, he has been unwavering in his demand for student-athlete accountability, on the field and off it. -

DENVER BRONCOS NEWS RELEASE Week 1 • Denver (0-0) Vs

DENVER BRONCOS NEWS RELEASE Week 1 • Denver (0-0) vs. Kansas City (0-0) • INVESCO Field at Mile High • 6:30 p.m. (MDT) BRONCOS BATTLE DIVISION RIVAL KANSAS CITY IN MEDIA RELATIONS CONTACT INFORMATION SEASON OPENER AT INVESCO FIELD AT MILE HIGH Jim Saccomano (303) 649-0572 [email protected] Let the games begin! The Paul Kirk (303) 649-0503 [email protected] Denver Broncos kickoff the Mark Cicero (303) 649-0512 [email protected] 2004 season at home against Patrick Smyth (303) 649-0536 [email protected] their division rival, the Rebecca Villanueva (303) 649-0598 [email protected] Kansas City Chiefs, on Sunday, Sept. 12 at INVESCO WWW.DENVERBRONCOS.COM/MEDIAROOM The Denver Broncos have a media-only website, which was Field at Mile High. The game created to assist accredited media in their coverage of the will be shown in the national Broncos. By going to www.DenverBroncos.com/Mediaroom, spotlight of ESPN’s Sunday members of the press will find complete statistical packages, Night Football (and locally on press releases, rosters, updated player and coach bios, the 2004 KUSA-TV, Channel 9) with Broncos Media Guide, game recaps and much more. Feature the kickoff scheduled for 6:30 p.m. (MDT). clippings are also available as one complete packet, and broken This is the fourth time these teams have faced each other in down individually by player and coach. Game clippings will also be the season opener. The Broncos hold a 3-1 advantage, with all posted weekly throughout the season. -

P:\Pag\20220828\Tabs\Section\T\42\42.Qxd (Page 1)

42 DETROIT LIONS 2002 FOOTBALL PREVIEW High hopes Lions dream big after a nightmare of a season The Associated Press DETROIT (AP) — Yes, the Detroit Silverdome — for the first time since A lot of hopes are riding on the Lions’ first draft pick Joey Harrington, above, a former Lions are talking about winning the 1974 to play in Ford Field, an Oregon signal-caller. Harrington is slated to come off the bench to open the season, Super Bowl this season. impressive $500 million stadium. say the Lions’ brass (at left) GM Matt Millen (right) and coach Marty Mornhinweg. One year after being the butt of “I think those two facilities will be jokes and receiving national atten- worth a win or two,” cornerback 2002 SCHEDULE LIONS 2001 STATS tion because they had a chance to Todd Lyght said. “Seriously.” be the first 0-16 team — with an 0- Besides the new stadium, they Date Opponent Time PASSING Sept. 8 at Miami 1 p.m. 12 start — they are dreaming big. also have a lot of new players, ATT-COMP PCT YDS TD INT RTG Sept. 15 at Carolina 1 p.m. Real big. including a pair of young and talent- Charlie Batch 341-198 .581 2392 12 12 78.6 Team presi- ed quarterbacks. Sept. 22 vs. Green Bay 4 p.m. Sept. 29 vs. New Orleans 1 p.m. Mike McMahon 115-53 .461 671 3 1 69.9 dent Matt Detroit let a lot of longtime Lions Ty Detmer 151-92 .609 906 3 10 56.9 Millen, a for- Oct. -

Nfl Draft Picks by Round

RECORD BOOK NNFLFL DDRAFTRAFT PPICKSICKS BBYY RROUNDOUND FIFTH ROUND 12TH ROUND 19TH ROUND 1946 Gay Adelt (Washington) 1966 John Stipech (Washington) 1946 Lawrence Mauss (Philadelphia) 1956 Herb Nakken (Los Angeles) 1968 Bob Trumpy (Cincinnati) 1948 Barney Hafen (Detroit) 1967 Richard Tate (Green Bay) 1954 Don Rydalch (Pittsburgh) 1974 Steve Odom (Green Bay) 13TH ROUND 1984 Andy Parker (L.A. Raiders) 1946 Reed Nostrum (Chicago) 20TH ROUND 1986 Erroll Tucker (Pittsburgh) 1953 Ray Westort (Philadelphia) 1948 Frank Nelson (Boston Yanks) 1995 Lance Scott (Arizona) 1955 Don Henderson (Detroit) 1950 Joe Tangaro (N.Y. Giants) 2010 Robert Johnson (Tennessee) 1970 Dave Smith (Green Bay) 1954 Jim Durrant (Detroit) 2010 David Reed (Baltimore) 1974 Gary Keller (Minnesota) 2010 Stevenson Sylvester (Pittsburgh) 1975 Willie Armstead (Cleveland) 21ST ROUND 1953 Jim Dublinski (Washington) SIXTH ROUND 14TH ROUND 1958 Everett Jones (Pittsburgh) 1938 Karl Schleckman (Detroit) 1940 Pete Bogden (Los Angeles) 1939 Bernie McGarry (Cleveland Rams) 1961 Ken Peterson (Minnesota) 22ND ROUND 1958 Merrill Douglas (Chicago) 1965 Frank Andruski (San Francisco) 1948 Tally Stevens (Pittsburgh) 1982 Jack Campbell (Seattle) 1970 Ray Groth (St. Louis) 1949 Gil Tobler (Detroit) 1998 Chris Fuamatu-Ma’afala (Pittsburgh) 1974 Don Van Galder (Washington) 2000 John Frank (Philadelphia) 23RD ROUND 2000 Mike Anderson (Denver) 15TH ROUND 1951 Dave Cunningham (Yanks) 2003 Lauvale Sape (Buffalo) 1942 Mac Speedie (Detroit) 1958 Larry Fields (San Francisco) 2005 Chris Kemoeatu (Pittsburgh) 1946 Stan Stapley (New York Giants) 2009 Brice McCain (Houston) 1963 Jerry Overton (Dallas) 24TH ROUND 1967 Robert Woodson (Oakland) 1955 Max Pierce (St. Louis) SEVENTH ROUND Alex Smith was the No. 1 pick in the 1952 Wes Gardner (Detroit) 16TH ROUND 26TH ROUND 2005 NFL Draft—going to the San 1954 Jack Cross (Detroit) 1954 Charlie Grant (Philadelphia) 1956 Jack Kammerman (Cleveland) Francisco 49ers. -

Utah Football History

DECADEUTAH 2009 SUGAR BOWL CHAMPION FOOTBALLS TWO BCS BOWLS IN FIVE YEARS EIGHT CONSECUTIVE BOWL WINS NO. 2 AP RANKING 2008 MWC CHAMPIONS FOUR MWC TITLES IN THE LAST DECADE 2009 SUGAR BOWL CHAMPIONS TWO BCS BOWLS IN FIVE YEARS EIGHT CONSECUTIVE BOWL WINS NO. 2 AP RANKING 2008 MWC CHAMPIONS FOUR MWC TITLES IN THE FIRST-TEAM ALL-CONFERENCE ALL-SKYLINE CONFERENCE ALL-WESTERN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE 1938 . .Bruce Balkan, E Norm Thompson, S Leonard McGarry, T Marv Bateman, K Ernest Baldwin, C 1971 . .Marv Bateman, K Paul Snow, HB 1972 . .Bob Peterson, OT 1939 . .Paul Bogden, E Don Van Galder, QB Luke Pappas, T Fleming Jensen, PK Rex Geary, G Bob Pritchett, DE Bill Swan, QB Bob Fratto, DT 1940 . .Carlos Soffe, E 1973 . .Bill Powers, OG Floyd Spendlove, T Chuck Johanson, C Rex Geary, G Steve Odom, FL/RS Izzy Spector, HB Dan Marrelli, PK 1941 . .Floyd Spendlove, T Ron Rydalch, DT Izzy Spector, HB Steve Marshall, S 1942 . .LeGrande Gregory, E 1974 . .John Huddleston, LB Brigham Gardner, T 1976 . .Jack Steptoe, RS Burt Davis, C 1977 . .Rick Partridge, P Dewey Nelson, HB Tom McNamara, PK 1946 . .Dewey Nelson, HB 1978 . .Jeff Lyall, DE UTAH RECORD BOOK UTAH 1947 . .Bernard Hafen, E Tom Krebs, OG Bill Angelos, G Rick Partridge, P Cannon Parkinson, QB Defensive tackle Steve Clark was Defensive lineman John Frank was Frank Nelson, FB first-team all-WAC from 1980-81. 1948 . .Bernard Hafen, E first-team all-conference in 1998 – Tally Stevens, E Utah’s final year in the WAC – and 1962 . .Dave Costa, OT 1999. -

Morgan City Mudpuppies Trevor Kubatzke / Tim Robitz Erik Kramer

Morgan City Mudpuppies Relics Trevor Kubatzke / Tim Robitz Steve Carlson Erik Kramer QB Chicago Troy Aikman QB Dallas Thurman Thomas RB Buffalo Bernie Parmalee RB Miami Edgar Bennett RB Green Bay Ricky Watters RB Philadelphia Kordell Stewart R Pittsburgh Eric Metcalf R Atlanta Michael Jackson R Cleveland Terrance Mathis R Atlanta Anthony Miller R Denver Jerry Rice R San Francisco Norm Johnson K Pittsburgh Pete Stoyanovich K Miami ----- ----- Neil O'Donnell QB Pittsburgh Jay Novacek R Dallas Rodney Hampton RB NY Giants Kimble Anders RB Kansas City Darick Holmes RB Buffalo Johnnie Morton R Detroit Sherman Williams RB Dallas Al Del Greco K Houston Keenan McCardell R Cleveland Jacke Harris R Tampa Bay Wesley Walls R New Orleans Chris Miller QB St. Louis Jeff Hostetler QB Oakland Robert Green RB Chicago Nuclear Raiders Suicidal Maniacs Ed Kuligowski Allan Douglas Warren Moon QB Minnesota Brett Favre QB Green Bay Leroy Hoard RB Cleveland Terry Allen RB Washington OJ McDuffie R Miami Curtis Martin RB New England Shawn Jefferson R San Diego Jake Reed R Minnesota Lawrnece Dawsey R Tampa Bay Tony Martin R San Diego Tony McGee R Cincinnati Yancy Thigpen R Pittsburgh Jason Elam K Denver Kevin Butler K Chicago ----- ----- Steve Bono QB Kansas City Heath Shuler QB Washington Rick Mirer QB Seattle Larry Centers RB Arizona Derrick Alexander R Cleveland Adrian Murrell RB NY Jets Horace Copeland R Tampa Bay Mark Carrier R Carolina Will Moore R New England Napoleon Kaufman RB Oakland Tamarick Vanover R Kansas City Gus Frerotte QB Washington Mark Chumura R Green Bay Shannon Sharpe R Denver Crazy Mary Groove Puppies Big Red Dogs Jerry Trickie Cliff Runyard Jeff George QB Atlanta Jim Everett QB New Orleans Errict Rhett RB Tampa Bay Emmitt Smith RB Dallas Barry Sanders RB Detroit Marshall Faulk RB Indianapolis Isaac Bruce R St. -

Head Coach Urban Meyer

HEAD COACH URBAN MEYER rban Meyer was hired in December 2002 with Uthe expectation that he would bring conference championships and Top 25 rankings to the Utah football program. However, no one envisioned instant results, especially since the Utes were coming off a 5-6 season in 2002. No one, that is, except the high-energy Meyer, URBAN MEYER whose fast-paced approach is already becoming legendary in Record at Utah: 10-2 (1 year) college football circles. Career Record: 27-8 (3 years) In just his first year at Utah and third of the Year, and with 93-percent of the vote. year as a head coach, Meyer was named By tying the school win record of 10-2 EDUCATION National Coach of the Year by The Sporting and winning an outright conference champi- Cincinnati, 1986 News after leading the Utes to a 10-2 record, onship, the 2003 Ute team has been Bachelor’s in psychology their first outright conference championship anointed as the best in Utah football history. since 1957, a bowl victory and a final Much of the credit goes to Meyer, who Ohio State, 1988 national ranking of No. 21. Meyer became wasn’t even born the last time Utah won an Master’s in sports administration the first coach from Utah’s conference—and outright title and is the only coach in Utah’s just the second coach from a non-BCS 110-year football history to win a conference PERSONAL DATA program—ever to receive the coveted TSN championship in his first year.