The Early Spectrophotometric Evolution of V1186 Scorpii (Nova Scorpii 2004 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Comet Quarterly

International Comet Quarterly Links International Comet Quarterly ICQ: Recommended (and condemned) sources for stellar magnitudes Cometary Science Center Comet magnitudes Below is a list that observers may use to evaluate whether the source(s) that they are Central Bureau for Astro. Tel. contemplating using for visual or V stellar magnitudes are recommended or not. Unfortunately, many errors have been found over the years in the both the individual variable-star charts of Minor Planet Center the AAVSO (ICQ code AC) and the AAVSO Variable Star Atlas (code AA); those variable-star EPS/Harvard charts were designed for the purpose of tracking the relative variation in brightness of individual variable stars, and they frequently are not adequately aligned with the proper magnitude scale. The new Hipparcos/Tycho catalogues have had new codes implemented (see below). New additions (and changes in categories) will be made to the following list as new information reaches the ICQ. MAGNITUDE-REFERENCE KEY Second-draft recommendation list, 1997 Dec. 1. Updated 2007 April 20 and 2017 Oct. 4. NOTE: For visual magnitude estimation of comets, NEVER USE SOURCES for which the available star magnitudes are only brighter than the comet! For example, the SAO Star Catalog is very poor for magnitudes fainter than 9.0, and should NEVER be used on comets fainter than mag 9.5. The Tycho catalogue should not be used for comets fainter than mag 10.5. (Even CCD photometrists should be wary of using bright stars for very faint comets; it is always best to use comparison stars within a few magnitudes of the comet when doing CCD photometry.) NOTE: It is highly recommended that users of variable-star charts also specify (in descriptive notes to accompany the tabulated data) the specific chart(s) used for each observation; this information will be published in the ICQ. -

Abd Al-Rahman Al-Sufi and His Book of the Fixed Stars: a Journey of Re-Discovery

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Hafez, Ihsan (2010) Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi and his book of the fixed stars: a journey of re-discovery. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/28854/ 5.1 Extant Manuscripts of al-Ṣūfī’s Book Al-Ṣūfī’s ‘Book of the Fixed Stars’ dating from around A.D. 964, is one of the most important medieval Arabic treatises on astronomy. This major work contains an extensive star catalogue, which lists star co-ordinates and magnitude estimates, as well as detailed star charts. Other topics include descriptions of nebulae and Arabic folk astronomy. As I mentioned before, al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into Persian by al-Ṭūsī. It was also translated into Spanish in the 13th century during the reign of King Alfonso X. The introductory chapter of al-Ṣūfī’s work was first translated into French by J.J.A. Caussin de Parceval in 1831. However in 1874 it was entirely translated into French again by Hans Karl Frederik Schjellerup, whose work became the main reference used by most modern astronomical historians. In 1956 al-Ṣūfī’s Book of the fixed stars was printed in its original Arabic language in Hyderabad (India) by Dārat al-Ma‘aref al-‘Uthmānīa. -

Incidental Tables

Sp.-V/AQuan/1999/10/27:16:16 Page 667 Chapter 27 Incidental Tables Alan D. Fiala, William F. Van Altena, Stephen T. Ridgway, and Roger W. Sinnott 27.1 The Julian Date ...................... 667 27.2 Standard Epochs ...................... 668 27.3 Reduction for Precession ................. 669 27.4 Solar Coordinates and Related Quantities ....... 670 27.5 Constellations ....................... 672 27.6 The Messier Objects .................... 674 27.7 Astrometry ......................... 677 27.8 Optical and Infrared Interferometry ........... 687 27.9 The World’s Largest Optical Telescopes ........ 689 27.1 THE JULIAN DATE by A.D. Fiala The Julian Day Number (JD) is a sequential count that begins at Noon 1 Jan. 4713 B.C. Julian Calendar. 27.1.1 Julian Dates of Specific Years Noon 1 Jan. 4713 B.C. = JD 0.0 Noon 1 Jan. 1 B.C. = Noon 1 Jan. 0 A.D. = JD 172 1058.0 Noon 1 Jan. 1 A.D. = JD 172 1424.0 A Modified Julian Day (MJD) is defined as JD − 240 0000.5. Table 27.1 gives the Julian Day of some centennial and decennial dates in the Gregorian Calendar. 667 Sp.-V/AQuan/1999/10/27:16:16 Page 668 668 / 27 INCIDENTAL TABLES Table 27.1. Julian date of selected years in the Gregorian calendar [1, 2]. Julian day at noon (UT) on 0 January, Gregorian calendar Jan. 0.5 JD Jan. 0.5 JD Jan. 0.5 JD Jan. 0.5 JD 1500 226 8923 1910 241 8672 1960 243 6934 2010 245 5197 1600 230 5447 1920 242 2324 1970 244 0587 2020 245 8849 1700 234 1972 1930 242 5977 1980 244 4239 2030 246 2502 1800 237 8496 1940 242 9629 1990 244 7892 2040 246 6154 1900 241 5020 1950 243 3282 2000 245 1544 2050 246 9807 Century years evenly divisible by 400 (e.g., 1600, 2000) are leap years. -

Stars and Their Spectra: an Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89954-3 - Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B. Kaler Index More information Star index Stars are arranged by the Latin genitive of their constellation of residence, with other star names interspersed alphabetically. Within a constellation, Bayer Greek letters are given first, followed by Roman letters, Flamsteed numbers, variable stars arranged in traditional order (see Section 1.11), and then other names that take on genitive form. Stellar spectra are indicated by an asterisk. The best-known proper names have priority over their Greek-letter names. Spectra of the Sun and of nebulae are included as well. Abell 21 nucleus, see a Aurigae, see Capella Abell 78 nucleus, 327* ε Aurigae, 178, 186 Achernar, 9, 243, 264, 274 z Aurigae, 177, 186 Acrux, see Alpha Crucis Z Aurigae, 186, 269* Adhara, see Epsilon Canis Majoris AB Aurigae, 255 Albireo, 26 Alcor, 26, 177, 241, 243, 272* Barnard’s Star, 129–130, 131 Aldebaran, 9, 27, 80*, 163, 165 Betelgeuse, 2, 9, 16, 18, 20, 73, 74*, 79, Algol, 20, 26, 176–177, 271*, 333, 366 80*, 88, 104–105, 106*, 110*, 113, Altair, 9, 236, 241, 250 115, 118, 122, 187, 216, 264 a Andromedae, 273, 273* image of, 114 b Andromedae, 164 BDþ284211, 285* g Andromedae, 26 Bl 253* u Andromedae A, 218* a Boo¨tis, see Arcturus u Andromedae B, 109* g Boo¨tis, 243 Z Andromedae, 337 Z Boo¨tis, 185 Antares, 10, 73, 104–105, 113, 115, 118, l Boo¨tis, 254, 280, 314 122, 174* s Boo¨tis, 218* 53 Aquarii A, 195 53 Aquarii B, 195 T Camelopardalis, -

Hot Stars As Targets for Intensity Interferometry

Hot Stars as Targets for Intensity Interferometry Hannes Jensen Lund Observatory, Sweden Aims • Given recent progress in phase interferometry: which should be the prime observational targets for II? • What is least difficult to observe? • Starting point for observing programs, white papers, etc. Selection Criteria What makes a target suitable for II? • Bright High above background noise level, moonlight etc. • Hot S/N improves greatly with target temperature • Astronomically interesting Features on a (sub)milliarcsecond level. Deformation due to rapid rotation, pulsation, disks, winds, etc. The Bright Star Catalogue The Bright Star Catalogue contains the ~9000 brightest stars. Temperatures Effective temperatures were approximated with a polynomial fit to values from [Bessel et al, 1998, A&A333]. ~2600 objects are hotter than 9000 K and brighter than V=7 Final selection • 34 stars exist with (Teff > 9000 K ∧ V < 2) ∨ T eff > 25000 K • A few other interesting objects were added • Angular diameters from the CHARM2 compilation. [Richichi et al., 2005, A&A431, 773] Selected objects Temperature vs. apparent magnitude of selected stars. Circle size indicates angular diameter where available. 1 mas List of Objects Angular Rot. vel.* Name Spec. class Teff [K] V [mag] Notes size (mas) [km/s] Achernar, HR 472 1.9 250 B3Ve 15000 0.46 High rotational velocity, Be-star Rigel, HR 1713 2.4 30 B8Iab 9800 0.12 Emission line star, SN candidate Lambda Lep, HR 1756 70 B0.5IV 28000 4.29 Bellatrix, HR 1790 0.7 60 B2III 21000 1.64 Variable star Elnath, HR 1791 -

Three Editions of the Star Catalogue of Tycho Brahe*

A&A 516, A28 (2010) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201014002 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Three editions of the star catalogue of Tycho Brahe Machine-readable versions and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue F. Verbunt1 andR.H.vanGent2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Utrecht University, PO Box 80 000, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 URU-Explokart, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, PO Box 80 115, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 Institute for the History and Foundations of Science, PO Box 80 000, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 6 January 2010 / Accepted 3 February 2010 ABSTRACT Tycho Brahe completed his catalogue with the positions and magnitudes of 1004 fixed stars in 1598. This catalogue circulated in manuscript form. Brahe edited a shorter version with 777 stars, printed in 1602, and Kepler edited the full catalogue of 1004 stars, printed in 1627. We provide machine-readable versions of the three versions of the catalogue, describe the differences between them and briefly discuss their accuracy on the basis of comparison with modern data from the Hipparcos Catalogue. We also compare our results with earlier analyses by Dreyer (1916, Tychonis Brahe Dani Scripta Astronomica, Vol. II) and Rawlins (1993, DIO, 3, 1), finding good overall agreement. The magnitudes given by Brahe correlate well with modern values, his longitudes and latitudes have error distributions with widths of 2, with excess numbers of stars with larger errors (as compared to Gaussian distributions), in particular for the faintest stars. Errors in positions larger than 10, which comprise about 15% of the entries, are likely due to computing or copying errors. -

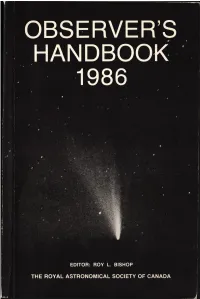

Observer's Handbook 1986

OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK 1986 EDITOR: ROY L. BISHOP THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA CONTRIBUTORS AND ADVISORS A l a n H. B a t t e n , Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, 5071 W. Saanich Road, Victoria, BC, Canada V8X 4M6 (The Nearest Stars). L a r r y D. B o g a n , Department of Physics, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada B0P 1X0 (Configurations of Saturn’s Satellites). Terence Dickinson, R.R. 3, Odessa, ON, Canada K0H 2H0 (The Planets). David W. Dunham, International Occultation Timing Association, P.O. Box 7488, Silver Spring, MD 20907, U.S.A. (Lunar and Planetary Occultations). Alan Dyer, Queen Elizabeth Planetarium, 10004-104 Ave., Edmonton, AB, Canada T5J 0K1 (Messier Catalogue, Deep-Sky Objects). Fred Espenak, Planetary Systems Branch, NASA-Goddard Space Flight Centre, Greenbelt, MD, U.S.A. 20771 (Eclipses and Transits). M arie Fidler, The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 136 Dupont St., Toronto, ON, Canada M5R 1V2 (Observatories and Planetaria). Victor Gaizauskas, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1A 0R6 (Solar Activity). R o b e r t F. G a r r is o n , David Dunlap Observatory, University of Toronto, Box 360, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada L4C 4Y6 (The Brightest Stars). Ian H alliday, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1A 0R6 (Miscellaneous Astronomical Data). W illiam Herbst, Van Vleck Observatory, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, U.S.A. 06457 (Galactic Nebulae). H e l e n S. H o g g , David Dunlap Observatory, University of Toronto, Box 360, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada L4C 4Y6 (Foreword). -

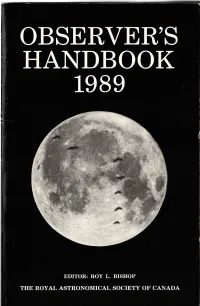

Observer's Handbook 1989

OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK 1 9 8 9 EDITOR: ROY L. BISHOP THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA CONTRIBUTORS AND ADVISORS Alan H. B atten, Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, 5071 W . Saanich Road, Victoria, BC, Canada V8X 4M6 (The Nearest Stars). L a r r y D. B o g a n , Department of Physics, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada B0P 1X0 (Configurations of Saturn’s Satellites). Terence Dickinson, Yarker, ON, Canada K0K 3N0 (The Planets). D a v id W. D u n h a m , International Occultation Timing Association, 7006 Megan Lane, Greenbelt, MD 20770, U.S.A. (Lunar and Planetary Occultations). A lan Dyer, A lister Ling, Edmonton Space Sciences Centre, 11211-142 St., Edmonton, AB, Canada T5M 4A1 (Messier Catalogue, Deep-Sky Objects). Fred Espenak, Planetary Systems Branch, NASA-Goddard Space Flight Centre, Greenbelt, MD, U.S.A. 20771 (Eclipses and Transits). M a r ie F i d l e r , 23 Lyndale Dr., Willowdale, ON, Canada M2N 2X9 (Observatories and Planetaria). Victor Gaizauskas, J. W. D e a n , Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1A 0R6 (Solar Activity). R o b e r t F. G a r r i s o n , David Dunlap Observatory, University of Toronto, Box 360, Richmond Hill, ON, Canada L4C 4Y6 (The Brightest Stars). Ian H alliday, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1A 0R6 (Miscellaneous Astronomical Data). W illiam H erbst, Van Vleck Observatory, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, U.S.A. 06457 (Galactic Nebulae). Ja m e s T. H im e r, 339 Woodside Bay S.W., Calgary, AB, Canada, T2W 3K9 (Galaxies). -

An Astrometric Search for a Stellar Companion to the Sun

LBL—23187 DE87 009642 An Astro metric Search for a Stellar Companion to the Sun Saul Perlmutter Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and The University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics 25 November 1986 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsi bility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Refer ence herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recom mendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily slate or reflect those of the United States Government, or any agency thereof. MASTER DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IS UNLIMITED An Astrometric Search for a Stellar Companion to the Sun Saul Perlmutter Abstract A companion star within 0.8 pc of the Sun has been postulated to explain a possible 26 Myr periodicity in mass extinctions of species on the Earth. Such a star would already be catalogued in the Yale Bright Star catalogue unless it is fainter than mv = 6.5; this limits the possible stellar types for an unseen compan ion to red dwarfs, brown dwarfs, or compact objects. -

Information Bulletin on Variable Stars

COMMISSIONS AND OF THE I A U INFORMATION BULLETIN ON VARIABLE STARS Nos April November EDITORS L SZABADOS K OLAH TECHNICAL EDITOR A HOLL TYPESETTING MB POCS ADMINISTRATION Zs KOVARI EDITORIAL BOARD E Budding HW Duerb eck EF Guinan P Harmanec chair D Kurtz KC Leung C Maceroni NN Samus advisor C Sterken advisor H BUDAPEST XI I Box HUNGARY URL httpwwwkonkolyhuIBVSIBVShtml HU ISSN 2 IBVS 4701 { 4800 COPYRIGHT NOTICE IBVS is published on b ehalf of the th and nd Commissions of the IAU by the Konkoly Observatory Budap est Hungary Individual issues could b e downloaded for scientic and educational purp oses free of charge Bibliographic information of the recent issues could b e entered to indexing sys tems No IBVS issues may b e stored in a public retrieval system in any form or by any means electronic or otherwise without the prior written p ermission of the publishers Prior written p ermission of the publishers is required for entering IBVS issues to an electronic indexing or bibliographic system to o IBVS 4701 { 4800 3 CONTENTS WOLFGANG MOSCHNER ENRIQUE GARCIAMELENDO GSC A New Variable in the Field of V Cassiop eiae :::::::::: JM GOMEZFORRELLAD E GARCIAMELENDO J GUARROFLO J NOMENTORRES J VIDALSAINZ Observations of Selected HIPPARCOS Variables ::::::::::::::::::::::::::: JM GOMEZFORRELLAD HD a New Low Amplitude Variable Star :::::::::::::::::::::::::: ME VAN DEN ANCKER AW VOLP MR PEREZ D DE WINTER NearIR Photometry and Optical Sp ectroscopy of the Herbig Ae Star AB Au rigae ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

How Astronomical Objects Are Named

How Astronomical Objects Are Named Jeanne E. Bishop Westlake Schools Planetarium 24525 Hilliard Road Westlake, Ohio 44145 U.S.A. bishop{at}@wlake.org Sept 2004 Introduction “What, I wonder, would the science of astrono- use of the sky by the societies of At the 1988 meeting in Rich- my be like, if we could not properly discrimi- the people that developed them. However, these different systems mond, Virginia, the Inter- nate among the stars themselves. Without the national Planetarium Society are beyond the scope of this arti- (IPS) released a statement ex- use of unique names, all observatories, both cle; the discussion will be limited plaining and opposing the sell- ancient and modern, would be useful to to the system of constellations ing of star names by private nobody, and the books describing these things used currently by astronomers in business groups. In this state- all countries. As we shall see, the ment I reviewed the official would seem to us to be more like enigmas history of the official constella- methods by which stars are rather than descriptions and explanations.” tions includes contributions and named. Later, at the IPS Exec- – Johannes Hevelius, 1611-1687 innovations of people from utive Council Meeting in 2000, many cultures and countries. there was a positive response to The IAU recognizes 88 constel- the suggestion that as continuing Chair of with the name registered in an ‘important’ lations, all originating in ancient times or the Committee for Astronomical Accuracy, I book “… is a scam. Astronomers don’t recog- during the European age of exploration and prepare a reference article that describes not nize those names. -

![Arxiv:2010.06108V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 6 Jul 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2344/arxiv-2010-06108v2-physics-hist-ph-6-jul-2021-4502344.webp)

Arxiv:2010.06108V2 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 6 Jul 2021

CONSTELLATIONS ACROSS CULTURES 1 Perceptual grouping explains similarities in constellations across cultures Charles Kemp1, Duane W. Hamacher2, Daniel R. Little1, and Simon J. Cropper1 1Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne 2School of Physics, University of Melbourne Author Note Charles Kemp https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9683-8737 Duane W. Hamacher https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3072-8468 Daniel R. Little https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3607-5525 Simon J. Cropper https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3574-6414 arXiv:2010.06108v2 [physics.hist-ph] 6 Jul 2021 Code and data are available at https://github.com/cskemp/constellations We acknowledge the Indigenous custodians of the traditional astronomical knowledge used in this paper, and thank Joshua Abbott, Celia Kemp, Bradley Schaefer and Yuting Zhang for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by ARC FT190100200, ARC DE140101600, the McCoy Seed Fund, the Laby Foundation, the Pierce Bequest, and by a seed grant from the Royal Society of Victoria. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Charles Kemp, Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] CONSTELLATIONS ACROSS CULTURES 2 Abstract Cultures around the world organise stars into constellations, or asterisms, and these groupings are often considered to be arbitrary and culture-specific. Yet there are striking similarities in asterisms across cultures, and groupings such as Orion, the Big Dipper, the Pleiades and the Southern Cross are widely recognized across many different cultures. Psychologists have informally suggested that these shared patterns are explained by Gestalt laws of grouping, but there have been no systematic attempts to catalog asterisms that recur across cultures or to explain the perceptual basis of these groupings.