Perennial Pepperweed Lepidium Latifolium L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Habitat Restoration Compendium Alyson L

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space PREP Reports & Publications (EOS) 2009 Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Habitat Restoration Compendium Alyson L. Eberhardt University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] David M. Burdick University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/prep Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Eberhardt, Alyson L. and Burdick, David M., "Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Habitat Restoration Compendium" (2009). PREP Reports & Publications. 102. https://scholars.unh.edu/prep/102 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in PREP Reports & Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hampton-Seabrook Estuary Habitat Restoration Compendium Alyson L. Eberhardt and David M. Burdick University of New Hampshire This project was funded by the NOAA Restoration Center in conjunction with the Coastal Zone Management Act by NOAA’s Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management in conjunction with the New Hampshire Coastal Program and US Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program through an agreement with the University of New Hampshire Hampton-Seabrook -

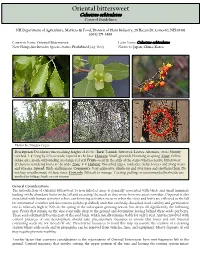

Oriental Bittersweet Orientalcelastrus Bittersweet Orbiculatus Controlcontrol Guidelinesguidelines

Oriental bittersweet OrientalCelastrus bittersweet orbiculatus ControlControl GuidelinesGuidelines NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Oriental Bittersweet Latin Name: Celastrus orbiculatus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan, China, Korea Photos by: Douglas Cygan Description: Deciduous vine reaching heights of 40-60'. Bark: Tannish, furrowed. Leaves: Alternate, ovate, bluntly toothed, 3-4'' long by 2/3’s as wide, tapered at the base. Flowers: Small, greenish, blooming in spring. Fruit: Yellow dehiscent capsule surrounding an orange-red aril. Fruits occur in the axils of the stems whereas native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) fruits at the ends. Zone: 4-8. Habitat: Disturbed edges, roadsides, fields, forests and along rivers and streams. Spread: Birds and humans. Comments: Very aggressive, climbs up and over trees and smothers them. Do not buy wreaths made of these vines. Controls: Difficult to manage. Cutting, pulling, or recommended herbicide use applied to foliage, bark, or cut-stump. General Considerations The introduction of Oriental bittersweet to non infested areas is generally associated with birds and small mammals feeding on the abundant fruits in the fall and excreting the seeds as they move from one area to another. Dispersal is also associated with human activities where earth moving activities occur or when the vines and fruits are collected in the fall for ornamental wreathes and decorations (which is prohibited) and then carelessly discarded. Seed viability and germination rate is relatively high at 90% in the spring of the subsequent growing season, but drops off significantly the following year. -

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation Project ID(s): R01Y19P01: Quinault Indian Nation, fiscal year 2019 Project area The project area (Figure 1) is restricted to the Quinault Indian Nation, bounded by Grays Harbor Co. Jefferson Co. and the Olympic National Park. Appendix A: USGS 7.5-minute Quadrangles: Queets, Salmon River West, Salmon River East, Matheny Ridge, Tunnel Island, O’Took Prairie, Thimble Mountain, Lake Quinault West, Lake Quinault East, Taholah, Shale Slough, Macafee Hill, Stevens Creek, Moclips, Carlisle. • < 0. Figure 1. QIN NWI+ 2019 project area (red outline). Source Imagery: Citation: For all quads listed above: See Appendix A Citation Information: Originator: USDA-FSA-APFO Aerial Photography Field Office Publication Date: 2017 Publication place: Salt Lake City, Utah Title: Digital Orthoimagery Series of Washington Geospatial_Data_Presentation_Form: raster digital data Other_Citation_Details: 1-meter and 1-foot, Natural Color and NIR-False Color Collateral Data: . USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles . USGS – NHD – National Hydrography Dataset . USGS Topographic maps, 2013 . QIN LiDAR DEM (3 meter) and synthetic stream layer, 2015 . Previous National Wetlands Inventories for the project area . Soil Surveys, All Hydric Soils: Weyerhaeuser soil survey 1976, NRCS soil survey 2013 . QIN WET tables, field photos, and site descriptions, 2016 to 2019, Janice Martin, and Greg Eide Inventory Method: Wetland identification and interpretation was done “heads-up” using ArcMap versions 10.6.1. US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) mapping contractors in Portland, Oregon completed the original aerial photo interpretation and wetland mapping. Primary authors: Nicholas Jones of SWCA Environmental Consulting. 100% Quality Control (QC) during the NWI mapping was provided by Michael Holscher of SWCA Environmental Consulting. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Spiranthes Diluvialis) and for Designated Weeds

2000 Survey of BLM-Managed Public Lands in Southwestern Wyoming for Ute Ladies Tresses (Spiranthes diluvialis) and for Designated Weeds Report Prepared for the BLM Rock Springs Field Office by George P. Jones, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (University of Wyoming) in partial fulfillment of Cooperative Agreement K910A970018, Task Order TO-13 April 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................i BACKGROUND................................................................................................................. 1 METHODS.......................................................................................................................... 1 RESULTS............................................................................................................................ 2 SPIRANTHES DILUVALIS .................................................................................. 2 WEEDS ................................................................................................................... 2 DISCUSSION ..................................................................................................................... 2 REFERENCES.................................................................................................................... 3 APPENDIX 1: DESCRIPTIONS OF STREAM SEGMENTS .........................................8 APPENDIX 2: ABUNDANCE OF THE DESIGNATED WEEDS IN EACH STREAM SEGMENT........................................................................................................................18 -

Lepidium Latifolium) Identification Perennial Pepperweed Plants Have Upright, Multi-Branched Stems, Growing from a Semi-Woody Crown and Creeping Rhizomes

Monthly Weed Post 1 May 2012 Perennial Pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium) Identification Perennial pepperweed plants have upright, multi-branched stems, growing from a semi-woody crown and creeping rhizomes. Plant grow 1-3 feet tall, but may reach eight feet in wet areas. Basal leaves have a prominent white mid rib and are up to 12 inches long and 3 inches wide. Leaf margins are entire or toothed. Stem leaves are smaller, lanceolate, and with a less prominent mid rib. Ball-like clusters of small white flowers grow at branch ends and bloom in early summer. Given adequate moisture, flowering may continue until fall. The seeds are in a pod-like structure called a silicle (see inset drawing). Perennial pepperweed may be confused with another member of the Brassicaceae family, whitetop (Cardaria spp.). Upper leaves of perennial pepperweed do not clasp the stem like whitetop. Additionally, perennial pepperweed siliciles are flattened, while whitetop silicles are round or inflated. Impacts Perennial pepperweed may be highly invasive given the right conditions. It can form dense stands which have the potential to displace native plants and animals, decrease plant diversity, and reduce nesting frequency of waterfowl in or near wetlands. Habitat Perennial pepperweed occurs in riparian areas, marshes, estuaries, irrigation channels, wetlands, and floodplains. It also occurs along roadsides, hay meadows, alfalfa fields, and rangeland habitats. It is less common in undisturbed areas. Spread Plants spread by seed, rhizomes, and root fragments. Seeds have no mechanism for long distance dispersal, but they are easily transported by water. Seeds have a mucilaginous cover which makes them buoyant. -

Species: Lepidium Latifolium

Species: Lepidium latifolium http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/leplat/all.html SPECIES: Lepidium latifolium Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Lepidium latifolium AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS ©John M. Randall/The Nature Conservancy AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Zouhar, Kris. 2004. Lepidium latifolium. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: LEPLAT SYNONYMS: Cardaria latifolia (L.) Spach [87] NRCS PLANT CODE [83]: LELA2 COMMON NAMES: perennial pepperweed broadleaved pepperweed tall whitetop 1 of 41 9/24/2007 4:32 PM Species: Lepidium latifolium http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/leplat/all.html TAXONOMY: The currently accepted name for perennial pepperweed is Lepidium latifolium L. (Brassicaceae) [22,29,31,36,38,41,42,43]. LIFE FORM: Forb FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: None OTHER STATUS: As of this writing (2004), perennial pepperweed is designated a noxious or prohibited weed or weed seed in at least 13 states in the United States and 1 Canadian province [84]. See the Invaders, Plants, or APHIS databases for more information. DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Lepidium latifolium GENERAL DISTRIBUTION ECOSYSTEMS STATES/PROVINCES BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS SAF COVER TYPES SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES GENERAL DISTRIBUTION: Perennial pepperweed is native to western Asia and southeastern Europe and now occurs from North Africa north through Europe to Norway and east to the western Himalayas. -

Documentazione Scientifica

DOCUMENTAZIONE SCIENTIFICA DOCUMENTAZIONE RISERVATA ALLA CLASSE MEDICA Relazioni Scientifiche UNIVERSITÀ DELLA CALABRIA Dipartimento di Scienze Farmaceutiche Lepidium meyenii (Maca) nel trattamento della Calvizie Stato dell’arte La perdita dei capelli , generalmente può non considerarsi una malattia, anche se è risaputo condizionare psicologicamente una persona che ne soffre quindi, incidere sulla sua qualità della vita. Le cause principali della caduta dei capelli sono di origine alimentare, atmosferica, dovute allo stress psico-fisico. Se si considera che la perdita da 50 a 100 capelli ogni giorno, è ritenuta normale (fisiologico), bisogna sottolineare che il primo “campanello d‘allarme” verso la condizione di calvizie è la perdita di capelli superiore alla cifra succitata. Per non andare incontro a calvizie pertanto, è necessario che tutti i capelli persi siano sostituiti. I capelli caduti, non ricrescono sempre poiché, in taluni casi, la matrice pilifera sostituisce il capello “morto” con uno di calibro nettamente inferiore ovvero può non sostituirlo affatto: in questo caso si ha a che fare con alopecia la cui entità dipende dal disegno assunto dalle aree che si sono sfoltite. La normale caduta fisiologica dei capelli aumenta nelle stagioni di transizione (autunno-primavera) perché l'uomo conserva una manifestazione ancestrale propria di altri mammiferi pelosi: la muta. Nei periodi da aprile a maggio e da settembre a novembre, alcuni ormoni attivano un processo sincronizzato di caduta: Si tratta di un fatto fisiologico che non è causa di calvizie definitiva1. La caduta dei capelli può dipendere anche dallo stress: condizioni psicofisiche difficili, soprattutto se prolungate, possono provocare, infatti, un aumento della caduta dei capelli, talora anche molto pronunciato. -

Control of Lepidium Latifolium and Restoration of Native Grasses

AN ABSTRACf OF THE THESIS OF Mar2aret S. Laws for the degree of Master of Science in Ran2eland Resources presented on November 23. 1999. Title: Control of Leoidium latifolium and Restoration of Native Grasses. ( Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: _ Lepidium latifolium L. (perennial pepperweed, LEPLA) is an exotic invader throughout western North America. At Malheur National Wildlife Refuge (MNWR) in southeast Oregon, it has invaded about 10% of meadow habitats that are important for wildlife. This study's objective was to determine the most effective and least environmentally harmful treatment to control this weed and restore native vegetation using integrated pest management techniques. During summer 1995, nine 0.24-ha plots in three meadows infested with L latifolium at MNWR were randomly assigned to a treatment with metsulfuron methyl herbicide, chlorsulfuron herbicide, disking, burning, herbicide (metsulfuron methyl or chlorsulfuron) then disking, herbicide (metsulfuron methyl or chlorsulfuron) then burning, or untreated. Changes in L latifolium ramet densities and basal cover of vegetation, litter, and bare soil were evaluated in 1996 and 1997. Sheep grazing was evaluated as a treatment for reduction in flower production along roadsides and levees during summer 1997. Revegetation treatments of seeding, transplanting or natural (untreated) revegetation were attempted at plots treated with chlorsulfuron, disking, chlorsulfuron then disking, and at untreated plots from October 1996 through September 1997. Chlorsulfuron was the most effective control treatment with greater than 97% reduction in L latifolium ramet densities two years after treatment Metsulfuron methyl was an effective control (greater than 93% reduction) for one year. Disking was ineffective. Burning was ineffective at the one site where sufficient fine fuels existed to carry fire. -

Final Report on Land Cover Mapping Methods: Map Zones 8 and 9

The Pacific Northwest Regional Gap Analysis Project Final Report on Land Cover Mapping Methods: Map Zones 8 and 9 1 May, 2006 Institute for Natural Resources Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA USDA-PNW Forest Sciences Laboratory, Corvallis, OR, USA This report represents the land cover portion of the final project report for Map Zones 8 and 9 of the Pacific Northwest Regional Gap Analysis Project i Final Report on Land Cover Mapping Methods: Map Zones 8 and 9, Pacific Northwest ReGAP Authors: James S. Kagan.a* Janet A. Ohmannb* Mathew J. Gregoryc Claudine Tobalsked John C. Hakd Jeremy Friede a Institute for Natural Resources, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA b Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Corvallis, Oregon c Forest Science Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon d Oregon Natural Heritage Information Center, Oregon State University, Portland, Oregon e Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Portland, Oregon Recommended Citation: Kagan, J.S., J.A. Ohmann, M.J. Gregory, C. Tobalske, J.C. Hak, and J. Fried. 2006. Final Report on Land Cover Mapping Methods, Map Zones 8 and 9, PNW ReGAP. Institute for Natural Resources, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Acknowledgements Much of this report is taken directly from the Southwest Regional Gap Analysis final report, by J.H. Lowry et al. (2006). The authors greatly appreciate their willingness to share their work. The work here was based on previous projects developed with other key individuals. Steve Knick and Steve Hanser of the USGS Snake River Field Station in Boise, both managed and facilitated the SageMap project, which provided the foundation of most of the vegetation data incorporated. -

Plants of Hot Springs Valley and Grover Hot Springs State Park Alpine County, California

Plants of Hot Springs Valley and Grover Hot Springs State Park Alpine County, California Compiled by Tim Messick and Ellen Dean This is a checklist of vascular plants that occur in Hot Springs Valley, including most of Grover Hot Springs State Park, in Alpine County, California. Approximately 310 taxa (distinct species, subspecies, and varieties) have been found in this area. How to Use this List Plants are listed alphabetically, by family, within major groups, according to their scientific names. This is standard practice for plant lists, but isn’t the most user-friendly for people who haven’t made a study of plant taxonomy. Identifying species in some of the larger families (e.g. the Sunflowers, Grasses, and Sedges) can become very technical, requiring examination of many plant characteristics under high magnification. But not to despair—many genera and even species of plants in this list become easy to recognize in the field with only a modest level of study or help from knowledgeable friends. Persistence will be rewarded with wonder at the diversity of plant life around us. Those wishing to pursue plant identification a bit further are encouraged to explore books on plants of the Sierra Nevada, and visit CalPhotos (calphotos.berkeley.edu), the Jepson eFlora (ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora), and CalFlora (www.calflora.org). The California Native Plant Society (www.cnps.org) promotes conservation of plants and their habitats throughout California and is a great resource for learning and for connecting with other native plant enthusiasts. The Nevada Native Plant Society nvnps.org( ) provides a similar focus on native plants of Nevada.