Raising a Monster Army: Energy Drinks, Masculinity, and Militarized Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAIN on Drugs 101 GATEWAY

BRAIN on DRUGs 101 GATEWAY. TRENDS . Markeng Recognion 2012 1 LT. Ed Moses, Rered 1 Ojecves • Recite number one cancer killer of women {#6 CDC source on slide} • List the three main areas of the brain in order of alcohol impairment {#36 Dr. John Duncan OK U • Idenfy the age of brain maturity {#37 Dr. Daniel Amen of www.amenclinics.com} 2 Target Markeng….Children 3 Our Children Targeted Parents Unaware In the lile world in which children have their existence, whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injusce. Charles Dickens 4 More Women Die every year due to Lung Cancer than Breast Cancer *2007 70,880 women died from Lung Cancer, while 40,460 women died from Breast Cancer. *Estimated by American Cancer Society 5 Smoking Rate vs. Cancer Rate About 24yrs #1 7th 6 7 8 Success trends cause Markeng Change Internal Medicine News 11/1/06 Cigaree Nicone Levels Increase 10% in 6 Years . Reports Commissioner Paul J. Cote Jr., of Massachuses Dept. of Public Health one of only 3 states that require tobacco co. to report yearly nicone yields 9 9 ‘07 Camel Ads • Pink Camels for Girls? 10 10 And the latest… VIRGINIA SLIMS “PURSE PACKS” 11 Camel Exoc Blends A few years ago, R.J. Reynolds introduced Camel Exotic Blends in a range of flavors, featuring unusual packaging that was bright and alluring. In 2006, RJR pulled this line of flavored cigarettes after signing a settlement with 39 state AG’s to stop marketing flavored cigarettes. -

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

Sustainability Report Monster Beverage Corporation

2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENT This Report contains forward-looking statements, within the meaning of the U.S. federal securities laws as amended, regarding the expectations of management with respect to our plans, objectives, outlooks, goals, strategies, future operating results and other future events including revenues and profitability. Forward-look- ing statements are generally identified through the inclusion of words such as “aim,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “drive,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “project,” “strategy,” “target,” “hope,” and “will” or similar statements or variations of such terms and other similar expressions. These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current knowledge and expectations and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties, many of which are outside of the control of the Company, that could cause actual results and events to differ materially from the statements made herein. For additional information about the risks, uncer- tainties and other factors that may affect our business, please see our most recent annual report on Form 10-K and any subsequent reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, including quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. Monster Beverage Corporation assumes no responsibility to update any forward-looking state- ments whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. 2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT #UNLEASHED TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS 1 COMPANY AT A GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SOCIAL 15 PRODUCT RESPONSIBILITY 37 ENVIRONMENTAL 45 GOVERNANCE 61 CREDITS AND CONTACT 67 INTRODUCTION MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS As Monster publishes its first Sustainability Report, we cannot ignore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

The Great White Hoax

THE GREAT WHITE HOAX Featuring Tim Wise [Transcript] INTRODUCTION Text on screen Charlottesville, Virginia August 11, 2017 Protesters [chanting] You will not replace us! News reporter A major American college campus transformed into a battlefield. Hundreds of white nationalists storming the University of Virginia. Protesters [chanting] Whose streets? Our streets! News reporter White nationalists protesting the removal of a Confederate statue. The setting a powder keg ready to blow. Protesters [chanting] White lives matter! Counter-protesters [chanting] Black lives matter! Protesters [chanting] White lives matter! News reporter The march spiraling out of control. So-called Alt-Right demonstrators clashing with counter- protesters some swinging torches. Text on screen August 12, 2017 News reporter (continued) The overnight violence spilling into this morning when march-goers and counter-protesters clash again. © 2017 Media Education Foundation | mediaed.org 1 David Duke This represents a turning point for the people of this country. We are determined to take our country back. We're going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump. That's what we believed in. That's why we voted for Donald Trump. Because he said he's going to take our country back. And that's what we gotta do. News reporter A horrifying scene in Charlottesville, as this car plowed into a crowd of people. The driver then backing up and, witnesses say, dragging at least one person. Donald Trump We're closely following the terrible events unfolding in Charlottesville, Virginia. We condemn, in the strongest possible terms, this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides. On many sides. -

A Culturally Based Healing Intervention for Commercially Sex Trafficked Native American Women

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers School of Social Work 5-2016 A Culturally Based Healing Intervention for Commercially Sex Trafficked Native American Women Jennifer Hintz St. Catherine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Hintz, Jennifer. (2016). A Culturally Based Healing Intervention for Commercially Sex Trafficked Native American Women. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/594 This Clinical research paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Work at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL HEALING 1 A Culturally Based Healing Intervention for Commercially Sex Trafficked Native American Women By Jennifer D. Hintz, B.S. MSW Clinical Research Paper Presented to the Faculty of the School of Social Work St. Catherine University and the University of St. Thomas St. Paul, Minnesota In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work Committee Members Rajean P. Moone, Ph.D., (Chair) Jim Bear Jacobs, M.A Sister Stephanie Spandl, MSW, LICSW The Clinical Research project is a graduation requirement for MSW students at St. Catherine University/University of St. Thomas School of Social Work in St. Paul, Minnesota and is conducted within a nine-month time frame to demonstrate facility with basic social work research methods. -

Vision Series 2018: “Where We're Going: Push Back the Darkness” Matthew 5:14-16 We Are on Week 2 of Our Vision Series

Vision Series 2018: “Where We’re Going: Push Back the Darkness” Matthew 5:14-16 We are on week 2 of our Vision Series, and as you’ve already heard this morning from our Vision Team members and specifically from Molly Pitkin, we are going to spend this time looking deeply into our new mission statement which was revealed last week after a year of prayer, learning, and listening. Again, Colonial’s mission is “To be the light of Christ in a hurting culture so that the lost are found, the broken are made whole, the fatherless find hope, and our city is blessed.” As Molly mentioned, this mission statement was “discovered” by a team of people who spent many, many hours together in prayer, study, conversation, and discernment. Again, the Vision Team Members included Steve Aliber, our current Clerk of Session; Jim Cannon, our former Clerk of Session; Brian Mack, our Elder of Strategic Planning; Ken Kurtz…a current Elder at Wornall; Kevin Nunnally…a recent Elder at Wornall; Meda Green…Chair of Deacons at Quivira; Molly Pitkin…high school youth leader at Quivira; Ken Blume…Executive Director of Programs and Ministries; and me as the Lead Pastor. We benefitted greatly from our facilitator, Ted Vaughn, who guided us through a wonderful process of discovery. Now, before I jump into unpacking the Mission Statement, let me address some of your questions that I’ve been asked over the past week. First, I was asked why words like “making disciples” and “doing everything for the glory of God” were left out of our mission statement. -

U-17 Goaltending Program Technical Curriculum

U-17 Goaltending Program Technical Curriculum U-17 Goaltending Program Technical Curriculum INTRODUCTION: GOALTENDING SKATING DRILLS To be a good goaltender you must be an efficient skater. Your goaltender does not necessarily have to be the fastest skater on the team, but the best in terms of control and mobility. Pushes from post to post and ability to get quickly to plays laterally are essential for goalies to be able to perform at a high level. Goaltenders must learn to push with strength and stop hard when needed. So when doing T-push or shuffle drills I suggest everything is done in sequence. Example: A coach should be calling out for the goalie to PUSH----STOP----PUSH----STOP------ PUSH----STOP etc. giving one second in between pushes. This will give the goaltender time to recover and will keep him from developing bad habits by doing the drill too fast. The ability for a goaltender to change directions quickly is also an absolute must as today’s game is a lot about trying to create a situation to get a goaltender moving in the wrong direction. In order to do this, and be effective, skating drills are a natural part of goaltender development. Hockey Canada 2007 1 U-17 Goaltending Program Technical Curriculum Drill Name & Description Letter Drills “T” • Goaltender starts in middle of the net • T-push to just above the crease, stop. • T-push to outside, stop, and back. • Emphasize stopping with outside foot to create proper transition Key Teaching Points • Knee bend • Outside leg stop • Balance G Drill Name & Description Letter Drills -

Sheet1 Page 1 Name of Drink Caffeine (Mg) 5 Hour Energy 60

Sheet1 Name of drink Size (mL) Caffeine (mg) 5 Hour Energy 60 Equivalent of a cup of coffee Amp Energy (Original) 710 213 Amp Energy (Original) 473 143 Amp Energy Overdrive 473 142 Amp Energy Re-Ignite 473 158 Amp Energy Traction 473 158 Bawls Guarana 473 103 Bawls Guarana Cherry 473 100 Bawls Guarana G33K B33R 296 80 Bawls Guaranexx Sugar Free 473 103 Beaver Buzz Black Currant Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Citrus Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Green Machine Energy 473 200 Big Buzz Chronic Energy 473 200 BooKoo Energy Citrus 710 360 BooKoo Energy Wild Berry 710 360 Cheetah Power Surge Diet 710 None? Frank's Energy Drink 500 160 Frank's Energy Drink Lime 250 80 Frank's Energy Drink Pineapple 250 80 Full Throttle Unleaded 473 141 Hansen's Energy Pro 246 39 Hardcore Energize Bullet Blue Rage 85.7 300 Hype Energy Pro (Special Edition) 355 114 Hype Energy MFP 473 151 Inked Chikara 473 151 Inked Maori 473 151 Jolt Endurance Shot 60 200 Jolt Orange Blast 695 220 Lost (Original) 473 160 Lost Five-O 473 160 Mini Thin Rush (6 Hour) 60 200 Monster (Original) 710 246 Monster Assault 473 164 Monster Energy (Original) 473 170 Monster Khaos 710 225 Monster Khaos 473 150 Monster M-80 473 164 Monster MIXXD 473 Monster Reduced Carb 473 140 NOS (Original) 473 200 NOS (Original)(Bottle) 650 343 NOS Fruit Punch 473 246.35 Premium Green Tea Energy 355 119 Premium Iced Tea Energy 355 102 Premium Pink Energy 355 120 Red Bull 250 80 Red Bull 355 113.6 Page 1 Sheet1 Red Rain 250 80 Rocket Shot 54 50 Rockstar Burner 473 160 Rockstar Burner 710 239 Rockstar Diet 473 160 -

Finding the Strength to Heal After Campus Unwanted Sexual Experiences: a Journey of Identity and Strength

Finding the Strength to Heal After Campus Unwanted Sexual Experiences: A Journey of Identity and Strength by Laura Sinko A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Nursing) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Denise Saint Arnault, Chair Associate Professor Terri Conley Assistant Professor Michelle Munro-Kramer Research Professor Robert J. Ploutz-Snyder Laura M. Sinko [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6021-4727 © Laura M. Sinko 2019 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the survivors intervieWed and surveyed through this project who trusted and inspired us with their stories of hurt, loss, and hope for a future without violence. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous funding from the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation, the University of Michigan Institute of Women and Gender, Sigma Theta Tau Rho Chapter, and the University of Michigan's Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies. I would also like to acknowledge the immense help of the Sexual Assault Prevention and AWareness Center at University of Michigan for expanding my knowledge of campus sexual violence as well as being an invaluable recruitment resource. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the amazing help and encouragement of my loved ones, committee members, and valued support people, particularly my chair Dr. Denise Saint Arnault. You believed in me during a time when I did not believe in myself. Without you this -

Mark Alan Smith Formatted Dissertation

Copyright by Mark Alan Smith 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Mark Alan Smith Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. Committee: Thomas J. Garza, Supervisor Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Neil R. Nehring David D. Kornhaber To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. by Mark Alan Smith. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2019 Dedication I would like to dedicate this work to Jesse Kelly-Landes, without whom it simply would not exist. I cannot thank you enough for your continued love and support. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Thomas J. Garza for all of his assistance, academically and otherwise. Additionally, I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Dr. Neil R. Nehring, and Dr. David D. Kornhaber for their invaluable assistance in this endeavor. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the vital support of Dr. Veronika Tuckerová and Dr. Vladislav Beronja in contributing to the defense of my prospectus. -

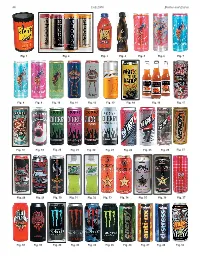

Bottles and Extras Fall 2006 44

44 Fall 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 32 Fig. 33 Fig. 34 Fig. 35 Fig. 36 Fig. 37 Fig. 38 Fig. 39 Fig. 40 Fig. 42 Fig. 43 Fig. 45 Fig. 46 Fig. 47 Fig. 48 Fig. 52 Bottles and Extras March-April 2007 45 nationwide distributor of convenience– and dollar-store merchandise. Rosen couldn’t More Energy Drink Containers figure out why Price Master was not selling coffee. “I realized coffee is too much of a & “Extreme Coffee” competitive market,” Rosen said. “I knew we needed a niche.” Rosen said he found Part Two that niche using his past experience of Continued from the Summer 2006 issue selling YJ Stinger (an energy drink) for By Cecil Munsey Price Master. Rosen discovered a company named Copyright © 2006 “Extreme Coffee.” He arranged for Price Master to make an offer and it bought out INTRODUCTION: According to Gary Hemphill, senior vice president of Extreme Coffee. The product was renamed Beverage Marketing Corp., which analyzes the beverage industry, “The Shock and eventually Rosen bought the energy drink category has been growing fairly consistently for a number of brand from Price Master. years. Sales rose 50 percent at the wholesale level, from $653 million in Rosen confidently believes, “We are 2003 to $980 million in 2004 and is still growing.” Collecting the cans and positioned to be the next Red Bull of bottles used to contain these products is paralleling that 50 percent growth coffee!” in sales at the wholesale level. -

Taj Mahal Andyt & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood

Taj Mahal Andy T & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood JOE BONAMASSA & DAVE & PHIL ALVIN NUMBER FIVE www.bluesmusicmagazine.com US $7.99 Canada $9.99 UK £6.99 Australia A$15.95 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © ART TIPALDI NUMBER FIVE 6 KEB’ MO’ Keeping It Simple 5 RIFFS & GROOVES by Art Tipaldi From The Editor-In-Chief 24 DELTA JOURNEYS 11 TAJ MAHAL “Jukin’” American Maestro by Phil Reser 26 AROUND THE WORLD “ALife In The Music” 14 NIKKI HILL 28 Q&A with Joe Bonamassa A Knockout Performer 30 Q&A with Dave Alvin & Phil Alvin by Tom Hyslop 32 BLUES ALIVE! Sonny Landreth / Tommy Castro 17 ANDY T & NICK NIXON Dennis Gruenling with Doug Deming Unlikely Partners Thorbjørn Risager / Lazy Lester by Michael Kinsman 37 SAMPLER 5 20 SELWYN BIRCHWOOD 38 REVIEWS StuffOfGreatness New Releases / Novel Reads by Tim Parsons 64 IN THE NEWS ANDREA LUCERO courtesy of courtesy LUCERO ANDREA FIRE MEDIA SHORE © PHOTOGRAPHY PHONE TOLL-FREE 866-702-7778 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB bluesmusicmagazine.com PUBLISHER: MojoWax Media, Inc. “Leave your ego, play the music, PRESIDENT: Jack Sullivan love the people.” – Luther Allison EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Art Tipaldi CUSTOMER SERVICE: Kyle Morris Last May, I attended the Blues Music Awards for the twentieth time. I began attending the GRAPHIC DESIGN: Andrew Miller W.C.Handy Awards in 1994 and attended through 2003. I missed 2004 to celebrate my dad’s 80th birthday and have now attended 2005 through 2014. I’ve seen it grow from its CONTRIBUTING EDITORS David Barrett / Michael Cote / Thomas J. Cullen III days in the Orpheum Theater to its present location which turns the Convention Center Bill Dahl / Hal Horowitz / Tom Hyslop into a dazzling juke joint setting.