Download Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

€˜Better Call Saul,€™ €˜Lodge 49€™ Get Premiere Dates, Photos

‘Better Call Saul,’ ‘Lodge 49’ Get Premiere Dates, Photos 06.01.2018 AMC revealed first-look photos for season four of Better Call Saul, as well as first-look photos for new series Lodge 49, which will debut immediately after the return of the Breaking Bad prequel. Better Call Saul will premiere August 6 at 9 p.m., followed by Lodge 49 at 10 p.m. "Monday nights have become a destination for our character-driven dramas, and we loved the idea of pairing these two series, which are similar in their darkly comedic tone and led by two charming yet complicated characters facing huge life moments," said David Madden, president of original programming for AMC, SundanceTV and AMC Studios. Better Call Saul follows the transformation of corporate attorney Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) into sleazy lawyer Saul Goodman, which is catalyzed by the death of his brother Chuck (Michael McKean) in season three. In the wake of his loss, Jimmy takes steps into the criminal world that will put his future as a lawyer - and his relationship with Kim (Rhea Seehorn) - in jeopardy. Chuck's death also deeply affects former colleagues Howard (Patrick Fabian) and Kim as well, putting the two of them once again on opposite sides of a battle sparked by the McGill brothers. Meanwhile, Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks) takes a more active role as Madrigal Ehrmantraut's (Jonathan Banks) newest (and most thorough) security consultant. It's a volatile time to be in the employ Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), as Hector's (Mark Margolis) collapse sends shock waves throughout the Albuquerque underworld and throws the cartel into chaos - tearing apart both Gus and Nacho's (Michael Mando) well-laid plans. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Indiebestsellers

Indie Bestsellers Fiction Week of 03.31.21 HARDCOVER PAPERBACK 1. Klara and the Sun 1. The Song of Achilles Kazuo Ishiguro, Knopf, $28 Madeline Miller, Ecco, $16.99 2. The Midnight Library 2. Circe Matt Haig, Viking, $26 Madeline Miller, Back Bay, $16.99 3. The Four Winds 3. The Rose Code Kristin Hannah, St. Martin’s, $28.99 Kate Quinn, Morrow, $17.99 ★ 4. The Consequences of Fear 4. The Dutch House Jacqueline Winspear, Harper, $27.99 Ann Patchett, Harper Perennial, $17 5. The Vanishing Half 5. Later Brit Bennett, Riverhead Books, $27 Stephen King, Hard Case Crime, $14.95 6. The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue ★ 6. The Book of Longings V.E. Schwab, Tor, $26.99 Sue Monk Kidd, Penguin, $17 7. Hamnet 7. Deacon King Kong Maggie O’Farrell, Knopf, $26.95 James McBride, Riverhead Books, $17 8. The Committed 8. Interior Chinatown Viet Thanh Nguyen, Grove Press, $27 Charles Yu, Vintage, $16 9. The Lost Apothecary 9. The Overstory Sarah Penner, Park Row, $27.99 Richard Powers, Norton, $18.95 10. We Begin at the End 10. The Sympathizer Chris Whitaker, Holt, $27.99 Viet Thanh Nguyen, Grove Press, $17 11. The Paris Library ★ 11. The Night Watchman Janet Skeslien Charles, Atria, $28 Louise Erdrich, Harper Perennial, $18 12. Anxious People 12. The House in the Cerulean Sea Fredrik Backman, Atria, $28 TJ Klune, Tor, $18.99 13. The Sanatorium 13. The Glass Hotel Sarah Pearse, Pamela Dorman Books, $27 Emily St. John Mandel, Vintage, $16.95 ★ 14. Eternal 14. Parable of the Sower Lisa Scottoline, Putnam, $28 Octavia E. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series A.P. Bio Handcuffed May 16, 2019 Jack agrees to help Mary dump her boyfriend and finds the task much harder than expected, meanwhile Principal Durbin enlists Anthony to do his dirty work. Jennifer Arnold, Directed by A.P. Bio Nuns March 14, 2019 As the newly-minted Driver's Ed teacher, Jack sets out to get revenge on his mother's church when he discovers the last of her money was used to buy a statue of the Virgin Mary. Lynn Shelton, Directed by A.P. Bio Spectacle May 30, 2019 After his computer breaks, Jack rallies his class to win the annual Whitlock's Got Talent competition so the prize money can go towards a new laptop. Helen and Durbin put on their best tuxes to host while Mary, Stef and Michelle prepare a hand-bell routine. Carrie Brownstein, Directed by Abby's The Fish May 31, 2019 When Bill admits to the group that he has Padres season tickets behind home plate that he lost in his divorce, the gang forces him to invite his ex-wife to the bar to reclaim the tickets. Betsy Thomas, Directed by After Life Episode 2 March 08, 2019 Thinking he has nothing to lose, Tony contemplates trying heroin. He babysits his nephew and starts to bond -- just a bit -- with Sandy. Ricky Gervais, Directed by Alexa & Katie The Ghost Of Cancer Past December 26, 2018 Alexa's working overtime to keep Christmas on track. But finding her old hospital bag stirs up memories that throw her off her holiday game. -

The Walking Dead X Gods of Boom Features

AMC’s The Walking Dead Invades Gods of Boom Game Insight’s mobile FPS Gods of Boom to Deliver a Themed Collaboration with AMC’s The Walking Dead Timed to the Mid-Season Premiere of Season 10 February 20th 2020 — To celebrate the mid-season premiere of The Walking Dead Season 10 this Sunday, February 23 on AMC, the network and Game Insight’s mobile game Gods of Boom are releasing a TWD-themed update. This unique integration will allow players to experience the action and excitement of GOB’s mobile first-person shooter gameplay in the setting of The Walking Dead universe. Starting today, players will fight their way through a seemingly abandoned settlement, slaying herds of walkers as well as Whisperers -- the formidable faction from the current season of the series. In-mission, players can also arm themselves with iconic weapons from the TV show, like Daryl’s trusty crossbow, Rick’s revolver and Negan’s infamous barbed-wire bat, “Lucille.” What’s more, and for the first time ever, Gods of Boom will be adding a new, limited-time only, full character skin to the game: walker hunter extraordinaire Daryl Dixon, as portrayed by Norman Reedus, whose likeness has been painstakingly recreated for the game. A Truly Authentic The Walking Dead Experience: Gods of Boom, the winner of several mobile game awards, is known for its fun, engaging, and tactical gameplay. Combining this with the AMC series’ thrilling atmosphere results in a unique and visceral experience for players; that of prowling the walker-filled streets of a ruined city, vigilant against threats both alive and dead. -

The Walking Dead” Universe

AMC STUDIOS SECURES INTERNATIONAL SALES WITH AMAZON PRIME VIDEO AND AMC NETWORKS INTERNATIONAL FOR THIRD SERIES IN “THE WALKING DEAD” UNIVERSE The Series Will Be Available on Prime Video Across Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, Africa and Europe, AMC Networks International Will Air the Series on AMC in Latin America, Spain and Portugal NEW YORK, NY, October 7, 2019 – AMC Studios announced today that it has successfully sold the third television series in the “The Walking Dead” universe around the world. Amazon Prime Video will carry the new series across Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe (excluding Spain and Portugal), while AMC Networks International will air it on AMC in Latin America, Spain and Portugal. The highly-anticipated 10-episode series is currently in production in the U.S. state of Virginia and is set to premiere in 2020. The third series in the expanding universe of “The Walking Dead” is produced and distributed by AMC Studios and will air in North America on AMC. “’The Walking Dead’ represents some of the most compelling and coveted IP in the world, so we are extremely thrilled to have lined up international distribution of the third television series in the expanding universe of ‘The Walking Dead’ with Amazon Prime Video and AMC Networks International,” said Valerie Cabrera, senior vice president of worldwide content distribution for AMC Studios. “A franchise and story that is rooted in our collective humanity, the appeal of ‘The Walking Dead’ crosses language and cultural barriers and we can’t wait to share this highly-anticipated series with fans around the globe next year.” The third installment of the franchise will feature two young female protagonists and focus on the first generation to come-of-age in the apocalypse as we know it. -

Redacted - for Public Inspection

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) AMC NETWORKS INC., ) Complainant, ) File No.:______________ ) v. ) ) AT&T INC., ) Defendant. ) TO: Chief, Media Bureau Deadline PROGRAM CARRIAGE COMPLAINT OF AMC NETWORKS INC. Tara M. Corvo Alyssia J. Bryant MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 900 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 434-7300 Scott A. Rader MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. Chrysler Center 666 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 (212) 935-3000 Counsel to AMC Networks Inc. August 5, 2020 REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................................................. 5 1. Jurisdiction ........................................................................................................................ 5 2. AMCN ................................................................................................................................ 5 3. AT&T ................................................................................................................................. 6 4. AT&T’s Public Assurances During the Civil Antitrust Litigation .............................. 7 5. AT&T’s Discriminatory Conduct .................................................................................. -

What Was Contemporary Literature?”

ENG 525.001—Contemporary Literature “What Was Contemporary Literature?” Fall 2013 T—7:20 pm-10:00 pm Room: HL 305 Instructor: (Christopher Gonzalez, PhD – Assistant Professor) Office Location: Hall of Languages (HL) 225 Office Hours: MF 11:00 am-1:00 pm and by appointment Office Phone: 903.886.5277 Office Fax: 903.886.5980 University Email Address: [email protected] NOTE: I reserve the right to revise the contents of this syllabus as I deem necessary. COURSE INFORMATION Materials – Textbooks, Readings, Supplementary Readings: Textbooks Required: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson The Marriage Plot by Jeffrey Eugenides The Middlesteins by Jami Attenberg Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe by Charles Yu Lost City Radio by Daniel Alarcón Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward The Round House by Louise Erdrich The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki A Visit from the Good Squad by Jennifer Egan I Am Not Sidney Poitier by Percival Everett (ENG 525 catalogue description): A study of post-1945 and recent literature in the United States and/or the United Kingdom and Ireland. Special emphasis will be placed on the ways in which national and international phenomena, both social as well as aesthetic, have informed an increasingly diverse understanding of literary texts. Topics for analysis could include late Modernism and its links to postmodern thought, Cold War writing, literatures of nationhood, post colonialism, the institutionalization of theory, multiculturalism and its literary impact, and the ever-growing emphasis placed on generic hybridity, especially as it concerns visual and electronic media. -

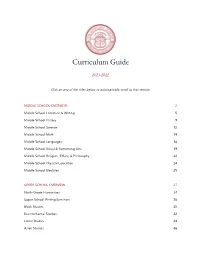

Curriculum Guide 21-22 MASTER

Curriculum Guide 2021-2022 Click on any of the titles below to automatically scroll to that section. MIDDLE SCHOOL OVERVIEW 2 Middle School Literature & Writing 5 Middle School History 9 Middle School Science 12 Middle School Math 14 Middle School Languages 16 Middle School Visual & Performing Arts 19 Middle School Religion, Ethics, & Philosophy 22 Middle School Physical Education 24 Middle School Electives 25 UPPER SCHOOL OVERVIEW 27 Ninth-Grade Humanities 34 Upper School Writing Seminars 38 Black Studies 40 Environmental Studies 42 Latinx Studies 44 Asian Studies 46 Class Studies 48 Queer Studies 50 Indigenous Studies 52 European Studies 54 Upper School Humanities Electives 56 Upper School Science 62 Upper School Math 66 Upper School Languages 71 Upper School Visual & Performing Arts 74 Upper School Religion, Ethics, and Philosophy 81 Upper School Physical Education 83 1 Middle School Overview The Middle School academic calendar is divided into semesters, which are named after feasts in the liturgical calendar: 1. Michaelmas Semester (Fall) 2. Epiphany Semester (Spring) Students in the Middle School share essential, formative experiences with their peers through much of the core curriculum, but also have some flexibility regarding how they fulfill requirements. COURSE OF STUDY Sixth Grade Michaelmas Semester Epiphany Semester Literature & Writing - Rules and Structures of Literature & Writing - Stories as Artifacts of Our Storytelling (and When to Break Them) Collective Memory History - The Origins of Humanity History - The Rise and Fall -

Dean's Nominations

DEAN’S NOMINATIONS - DRAMA OUTSTANDING DRAMA SERIES Better Call Saul Maniac Orange is the New Black Pose Queen Sugar Sharp Objects When They See Us OUTSTANDING LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA OUTSTANDING LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA • Bob Odenkirk – Better Call Saul • Kiernan Shipka – Chilling Adventures of • JK Simmons – Counterpart Sabrina • Wyatt Russell – Lodge 49 • Olivia Williamas – Counterpart • Jonah Hill – Maniac • Jodie Comer – Killing Eve • Kofi Siriboe – Queen Sugar • Emma Stone – Maniac • Jharrel Jerome – When They See Us • Dawn Lyen-Gardner – Queen Sugar • Amy Adams – Sharp Objects OUTSTANDING SUPPORTING ACTOR IN A DRAMA OUTSTANDING SUPPORTING ACTRESS IN A DRAMA • Jonathan Banks – Better Call Saul • Kathy Bates – American Horror Story • Harry Lloyd – Counterpart • Rhea Seehorn – Better Call Saul • Robin Lord Taylor – Gotham • Nazanin Boniadi – Counterpart • Tomasso Whitney – NXT • Carla Gugino – The Haunting of Hill House • Billy Porter – Pose • Danielle Brooks – Orange is the New Black • Michael K. Williams – When They See Us • Patricia Clarkson – Sharp Objects OUTSTANDING WRITING IN A DRAMA OUTSTANDING DIRECTING IN A DRAMA • Better Call Saul: “Winner”, written by Peter • Better Call Saul: “Something Stupid”, directed Gould & Thomas Schnauz by Deborah Chow • Maniac: “Utangatta”, written by Patrick • The Haunting of Hill House: “Two Storms”, Somerville directed by Mike Flanagan • Queen Sugar: “The Tree and Stone Were • Maniac: “Furs by Sebastian”, directed by Cary One”, written by Anthony Sparks Joji Fukanaga • Pose: “The Fever”, written -

Pontevedrarecorder.Com › Uploads › Files › 20200513-195310

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! May 14 - 20, 2020 has a new home at ALSO INSIDE: THE LINKS! th Find the latest 1361 S. 13 Ave., Ste. 140 streaming content Jacksonville Beach on Netflix, Hulu & Ask about our Amazon Prime Offering: 1/2 OFF Pages 3, 17, 22 · Hydrafacials All Services · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections · Botox & Fillers ‘Snowpiercer’ · Medical Weight Loss VIRTUAL CONSULTATIONS – Going off the rails on a post-apocalyptic train Get Skinny with it! Jennifer Connelly stars in “Snowpiercer,” premiering Sunday on TNT. (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Kathleen Floryan REALTOR® Broker Associate UNDER CONTRACT ODOM’S MILL | 4BR/3ba • 2,823 SF • $535,000 Here is a fantastic place to hang your heart with a lot of livability. This wonderful home enjoys views of a meandering lagoon and nature preserve, with no neighbors behind. In the heat of the day enjoy your screened pool/lanai that opens to an iron fenced back yard with an access gate to the water for kayak or SUP board. -

Conference Director Alfred Bendixen Texas A&M University

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 25th Annual Conference on American Literature May 22-25, 2014 Hyatt Regency Washington on Capitol Hill Washington, D.C. (202-737-1234) Conference Director Alfred Bendixen Texas A&M University Final Version May 7, 2014 This on-line draft of the program is designed to provide information to participants in our 25th conference It is now too late to make additional corrections to the printed program but changes can be made to the on-line version. Please note that the printed program will be available at the conference. Audio-Visual Equipment: The program also lists the audio-visual equipment that has been requested for each panel. The ALA normally provides a digital projector and screen to those who have requested it at the time the panel or paper is submitted. Individuals will need to provide their own laptops and those using Macs are advised to bring along the proper cable/adaptor to hook up with the projector. Please note that we no longer provide vcrs or overhead projectors or tape players. Registration: Participants should have pre-registered for the conference by going to the website at www.alaconf.org and either completing on line-registration which allows you to pay with a credit card or completing the registration form and mailing it along with the appropriate check to the address indicated. Individuals may register at the conference with cash or a check, but please note that we will not be able to accept credit cards at the hotel.