Global Animation Theory: International Perspectives at Animafest Zagreb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEDIGREE INSIGHTS... Adding to Her Optional Claiming Score at Gulfstream Get Pedigree Expert Andrew Caulfield=S Mar

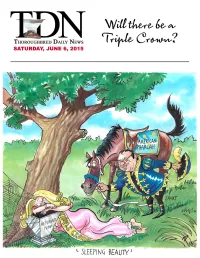

SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here PHAROAH FIT, READY TO WEAR THE CROWN AROUND THE HORN From the time Sir Barton became the first to sweep Today=s G1 Investec Derby seems to hinge on one the GI Kentucky Derby, GI Preakness S. and GI Belmont question, and only Golden Horn (GB) (Cape Cross {Ire}) S. in 1919 until Citation became the eighth to run the can supply the answer as he enters the final quarter- table in 1948, the most time mile of Tesio=s famed ultimate test of the that transpired between Thoroughbred. There is no doubt that Anthony successful Triple Crown bids Oppenheimer=s homebred has a distinct class edge over was the 11 years between Sir all of his rivals based on his emphatic success in the Barton and Gallant Fox in premier trial, York=s G2 Dante S. May 14, which was 1930. With his 31-length termed a Amini Derby@ at the time. Form, mentality and demolition of the field in 1973, physicality aside, Secretariat snapped a 25-year however, the bay enters drought, while Seattle Slew this race without all and Affirmed made it three boxes ticked, as he is Triple Crowns in the space of unproven at this trip and six years in 1977 and 1978, his pedigree does not respectively. Since then, 13 shout a mile and a half have tried and 13 have been Baffert and Zayat out loud. Under the denied, but Zayat Stables= second dam is a mix of at Belmont Thursday American Pharoah (Pioneerof NYRA/Coglianese stamina and speed, with Golden Horn Racing Post the Nile) can enter the annals the specialist miler of history as the 3-5 favorite in Rebecca Sharp (GB) (Machiavellian) sitting alongside the Saturday=s >Test of the Champion= on Long Island. -

Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art

School of Media Creative Arts and Social Inquiry (MCASI) Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art Kelsey Ashe Giambazi This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University July 2018 0 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Date: 15th July 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely express my thanks and gratitude to the following people: Dr. Ann Schilo for her patient guidance and supervisory assistance with my exegesis for the six-year duration of my candidacy. To learn the craft of writing with Ann has been a privilege and a joy. Dr. Anne Farren for her supervisory support and encouragement. To the staff of the Curtin Fashion Department, in particular Joanna Quake and Kristie Rowe for the daily support and understanding of the juggle of motherhood, work and ‘PhD land’. To Dr. Dean Chan for his impeccably thorough copy-editing and ‘tidying up’ of my bibliographical references. The staff in the School of Design and Art, in particular Dr. Nicole Slatter, Dr. Bruce Slatter and Dr. Susanna Castleden for being role models for a life with a balance of academia, art and family. My fellow PhD candidates who have shared the struggle and the reward of completing a thesis, in particular Fran Rhodes, Rebecca Dagnall and Alana McVeigh. -

AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL of TRADE MARKS 3 March 2011

Vol: 25, No. 9 3 March 2011 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it on our website (www.ipaustralia.gov.au) by using the "Journals" link on the home page. The Australian Official Journal of Trademarks is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 3 March 2011 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes. 2665 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed. 2665 Applications for Extension of Time . 2665 Applications for Amendment . 2665 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection . 2338 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1407400 to 1408941. 2317 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed. 2666 Withdrawn. 2667 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Matters Initial Assessment Given by the ACCC. 2669 Cancellations of Entries in Register . 2669 Corrigenda . 2672 Notices . 2664 Opposition Proceedings . 2662 Removal/Cessation of Protection for Non-use Proceedings . 2670 Renewal of Registration/IR . 2670 Trade Marks Registered/Protected . 2662 Trade Marks Removed from the Register/IRs Expired . 2671 This Page Left Intentionally Blank For Information on the following please see our website: www.ipaustralia.gov.au or contact our Customer Service Network on 1300651010 Editorial enquiries Contact information Freedom of Information ACT Professional Standards Board Sales Requests for Information under Section 194 (c) Country Codes Trade Mark and Designs Hearing Sessions INID (Internationally agreed Numbers for the Indentification of Data) ‘INID’ NUMBERS in use on Australian Trade Mark Documents ‘INID’ is an acronym for Internationally agreed Numbers for the Identification of Data’ (200) Data Concerning the Application. -

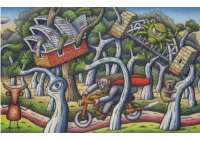

Selected Artworks by Chris O'doherty Aka Reg Mombassa Viewing By

SELECTED ARTWORKS BY CHRIS O’DOHERTY AKA REG MOMBASSA VIEWING BY APPOINTMENT ONLY Christopher O’Doherty, also known as Reg Mombassa, is an Australian musician and artist. He is known for his membership in bands Mental as Anything, Dog Trumpet and The Pinks. He worked with Mambo Graphics designing T-shirts and posters since 1986 and exhibited paintings, drawings and prints at Watters Gallery from 1975 to 2018. Beneath the humour in his work lies the expression of serious insights and sympathies. O’Doherty’s oeuvre is shaped from allegorical landscapes that create lingering, enigmatic sensations to both invite and unsettle his audience. His depictions of the familiar Australian landscape are imbued with an atmosphere of the immaterial to build a soft pulsing anticipation and gnawing stillness within his work. In the words of Australian art historian Chris McAuliffe, “In O’Doherty’s hands, every horizon hides an unreachable place where we long to be, every hillside implies an opposing slope that we’ll never know”. His diverse range of projects also includes taking part in solo and group art shows in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, USA, France, Britain, China and Thailand. He has had a survey show at the S.H. Ervin gallery in 2007 and Manly Gallery and Museum in 2018 with his brother Peter O'Doherty. His designs were featured in the Closing Ceremony of the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, and he designed the graphics for the 2013 Sydney New Year’s Eve celebrations. In 2001 the Victorian Tapestry Workshop invited Reg to contribute a design for a 2 metre square section of a 43.5 metre long Federation Tapestry to be completed and installed in the Melbourne Museum. -

Australian Customs Noctice 2003/65

AUSTRALIAN CUSTOMS NOTICE NO. 2003/65 Notices of Objection to Importation Trade Marks Act 1995 The Trade Marks Act 1995 allows the registered owner, or in certain circumstances, the authorised user of a trademark to object to the importation of goods which infringe their trademark. The registered owner, or authorised user does this by lodging a Notice of Objection with the Australian Customs Service (Customs). Unless revoked, a Notice of Objection remains in force for a period of two years from the date of commencement. The attached Schedule sets out the registered owners and authorised users who have lodged Notices of Objection under the Trade Marks Act 1995, since publication of Australian Customs Notice 2003/61. The Notices notify the objections of these registered owners and authorised users to the importation of goods which infringe their trade mark or trade marks. Descriptions of the relevant trade marks are also set out in the Schedule. For each particular trade mark described, the Schedule makes reference to a particular “class” of goods. This refers to the classes of goods prescribed in Schedule 1 to the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 and along with a description of the goods, is used to describe the type of goods for which the particular trade mark is registered. Prospective importers of such goods should seek further advice from Customs regarding the ambit of any Notice of Objection set out in the Schedule. Where goods of the kind referred to manufactured outside and imported into Australia: - have applied to them, or in relation to them, a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, a trade mark listed in the Schedule; and - fall within a class of goods for which the relevant trade mark is registered, they are liable to be seized by Customs unless it can be established that: - the goods are being imported otherwise than for the purposes of trade (sale, lease, hire, etc.); or - the goods do not infringe the relevant trade mark. -

Australian Customs Notice No. 2005/69

AUSTRALIAN CUSTOMS NOTICE NO. 2005/69 Notices of Objection to Importation - Trade Marks Act 1995 The Trade Marks Act 1995 allows the registered owner, or in certain circumstances, the authorised user of a trademark to object to the importation of goods which infringe their trademark. The registered owner, or authorised user does this by lodging a Notice of Objection with the Australian Customs Service (Customs). Unless revoked, a Notice of Objection remains in force for a period of two years from the date of commencement. The attached Schedule sets out the registered owners and authorised users who have lodged Notices of Objection under the Trade Marks Act 1995 since September 2005 (ACN 2005/48). The Notices notify the objections of these registered owners and authorised users to the importation of goods, which infringe their trade mark or trade marks. Descriptions of the relevant trade marks are also set out in the Schedule. A detailed list of all current Notices of Objection is available at http://cww.customs.gov.au/internet/site/page4387.htm For each particular trademark described, the Schedule makes reference to a particular “class” of goods. This refers to the classes of goods prescribed in Schedule 1 to the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 and along with a description of the goods, is used to describe the type of goods for which the particular trade mark is registered. Prospective importers of such goods should seek further advice from Customs regarding the ambit of any Notice of Objection set out in the Schedule. Where goods of the -

REG MOMBASSA 45 X 52Cm Christopher O’Doherty, Also Known As Reg Museum in 2018 with His Brother Peter O’Doherty

Above Artificial General Intelligence: Robot Smalltalk 2019 Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 32 x 25cm Right Robot on a rearing horse, Blueland 2019 Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 52 x 35cm Cover Mambo 30 2014 Digital reproduction framed 35 x 28cm Left Robot riding a horse 2019 THE CLAYTON UTZ Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 37 x 51cm ART PARTNERSHIP Left Replacing a differential, South Western NSW 2001 Charcoal and coloured pencil - Image courtesy of Tony Lopes on paper REG MOMBASSA 45 x 52cm Christopher O’Doherty, also known as Reg Museum in 2018 with his brother Peter O’Doherty. Mombassa, is an Australian musician and artist. He His designs were featured in the Closing Ceremony The Clayton Utz Art Partnership is known for his membership in bands Mental as of the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, and he Anything, Dog Trumpet and The Pinks. He worked designed the graphics for the 2013 Sydney New The Clayton Utz Art Partnership brings together a The uniquely curated program allows both artists to with Mambo Graphics designing T-shirts and posters Year’s Eve celebrations. In 2001 the Victorian unique collaboration between two outstanding explore and display their work in one of Australia’s since 1986 and exhibited paintings, drawings and Tapestry Workshop invited Reg to contribute a Australian artists and our firm. leading corporate environments. Guests visiting the prints at Watters Gallery from 1975 to 2018. design for a 2 metre square section of a 43.5 metre exhibition will have an opportunity to explore the long Federation Tapestry to be completed and Each exhibition presents an opportunity to artwork in an intimate and innovative environment. -

Australian & International

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 182, 2016 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW P: (02) 9663 4848 E: [email protected] W: joseflebovicgallery.com 1. “Not Dead Yet!” or “The Counterfeit [Gold Rush]” Theatre JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY Royal, Glasgow, 1866. Letterpress theatre playbill, 75.4 x 25.2cm. Established 1977 Trimmed left margin, repaired minor tears and old folds, slight offset. Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) Linenbacked. $1,100 This playbill, dated Friday, 8th June, 1866, initially covers two plays, Faust & Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW Marguerite! and Quite a Romance!, before mentioning a play on the Gold Rush in Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia Bendigo, Australia. The play was adapted from the novel Not dead yet by the English author John Cordy Jeaffreson (1831-1901), and was published in 1864. Three Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 scenes in the second act are set on the Bendigo gold diggings in the year 1862. Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com The playbill text includes “In rehearsal, and will shortly be produced, a three act drama by [actor] David Fisher with sensational effects and new scenery, Open: Monday to Saturday from 1-6pm by chance or by appointment. founded on actual occurrences, as narrated in the novel by J.C. Jeffreson [sic], which furnishes portions of the story of this play, called Not dead yet! or The Counterfeit: a tale of the times both in England and Australia. -

The Clayton Utz Art Partnership Is Known for His Membership in Bands Mental As of the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, and He Anything, Dog Trumpet and the Pinks

Above Artificial General Intelligence: Robot Smalltalk 2019 Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 32 x 25cm Right Robot on a rearing horse, Blueland 2019 Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 52 x 35cm Cover Mambo 30 2014 Digital reproduction framed 35 x 28cm Left Robot riding a horse 2019 THE CLAYTON UTZ Charcoal and coloured pencil on paper 37 x 51cm ART PARTNERSHIP Left Replacing a differential, South Western NSW 2001 Charcoal and coloured pencil - Image courtesy of Tony Lopes on paper REG MOMBASSA 45 x 52cm Christopher O’Doherty, also known as Reg Museum in 2018 with his brother Peter O’Doherty. Mombassa, is an Australian musician and artist. He His designs were featured in the Closing Ceremony The Clayton Utz Art Partnership is known for his membership in bands Mental as of the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, and he Anything, Dog Trumpet and The Pinks. He worked designed the graphics for the 2013 Sydney New The Clayton Utz Art Partnership brings together a The uniquely curated program allows both artists to with Mambo Graphics designing T-shirts and posters Year’s Eve celebrations. In 2001 the Victorian unique collaboration between two outstanding explore and display their work in one of Australia’s since 1986 and exhibited paintings, drawings and Tapestry Workshop invited Reg to contribute a Australian artists and our firm. leading corporate environments. Guests visiting the prints at Watters Gallery from 1975 to 2018. design for a 2 metre square section of a 43.5 metre exhibition will have an opportunity to explore the long Federation Tapestry to be completed and Each exhibition presents an opportunity to artwork in an intimate and innovative environment. -

T-Shirts Place of Box Id No

T-shirts Place of Box Id No. Title Creator Date publication Publisher Description Subjects TXT001 1 The quilt : Australian AIDS Memorial 1994 Sydney, NSW, AIDS Memorial Quilt Singlet. Words superimposed on rectangular design. Additional HIV/AIDS Quilt Project Australia Project text: "Sydney Display - Darling Harbour - 22nd-23rd January 1994". Cotton, mauve and black lettering on a white background. TXT001 2 1996 AIDS Awareness Week Tour 1996 Sydney, NSW, Outline sketch of two human figures (brown) wrapped together HIV/AIDS Australia by a red ribbon. Additional text: "Proudly sponsored by Fitpack, Needle Syringe Transportation Solutions : Sydney and Metropolitan Areas, Tamworth, Gunnedah, Narrabri, Moree, Bingara, Tenterfield, Inverell, Glen Innes, Armidale, Wollongong, Nowra, Grafton, Maclean, Lismore, Murwillumbah, Tweed Heads, Goulburn, Queanbeyan Cooma, Bega, Narooma, Mouruya, Young, The Entrance, Terrigal, Tuggerah, Woy Woy, Nepean, Penrith, Blue Mountains, Albury, Wagga, Wagga, Orange, Broken Hill, Wilcannia. World AIDS Day, Australia, December 1st 1996". Cotton, brown and red lettering on a fawn background. TXT001 3 [Red ribbon with rainbow patch] Red ribbon with rainbow patch, cotton on a black background. HIV/AIDS TXT001 4 Mars Bar 1993 Adelaide, SA, Mars Bar Hotel Cross of male and female figures, cotton, black lettering on a Venues Australia white background. TXT001 5 2001 Pride March Victoria : Embrace S., Antonia 2001 Melbourne, Vic, Pride March River and banks with two trees. Additional text: "Primus", cotton, Pride diversity Australia black and white lettering on a white background. TXT001 8 ICAAP Volunteer 2001 Melbourne, Vic, International Circles of stylised people around a ribbon, logo on sleeves. Cotton, HIV/AIDS; Australia Congress on AIDS in white lettering on a red background. -

Journal No. 015/2012

13 April 2012 Trade Marks Journal No. 015/2012 TRADE MARKS JOURNAL TRADE MARKS JOURNAL SINGAPORE SINGAPORE TRADE PATENTS TRADE DESIGNS PATENTS MARKS DESIGNS MARKS PLANT VARIETIES © 2012 Intellectual Property Office of Singapore. All rights reserved. Reproduction or modification of any portion of this Journal without the permission of IPOS is prohibited. Intellectual Property Office o f Singapore 51 Bras Basah Road #04-01, Manulife Centre Singapore 189554 Tel: (65) 63398616 Fax: (65) 63390252 http://www.ipos.gov.sg Trade Marks Journal No. 015/2012 TRADE MARKS JOURNAL Published in accordance with Rule 86A of the Trade Marks Rules. Contents Page 1. General Information i 2. Practice Directions iii 3. Notices and Information (A) General xii (B) Collective and Certification Marks xxxiv (C) Forms xxxv (D) eTrademarks xxxix (E) International Applications and Registrations under the Madrid Protocol xli (F) Classification of Goods and Services xlvii (G) Circulars Related to Proceeding Before The Hearings And Mediation Division lxvi 4. Applications Published for Opposition Purposes (Trade Marks Act, Cap. 332, 1999 Ed.) 1 5. International Registrations filed under the Madrid Protocol Published for Opposition Purposes (Trade Marks Act, Cap. 332, 1999 Ed.) 128 6. Changes in Published Applications Errata 225 Applications Amended after Publication 228 Trade Marks Journal No. 015/2012 Information Contained in This Journal The Registry of Trade Marks does not guarantee the accuracy of its publications, data records or advice nor accept any responsibility for errors or omissions or their consequences. Permission to reproduce extracts from this Journal must be obtained from the Registrar of Trade Marks. Trade Marks Journal No. -

Annual Report 2007

ANNUAL REPORT POWERHOUSE MUSEUM POWERHOUSE DISCOVERY CENTRE: 07-08 COLLECTION STORES AT CASTLE HILL 500 Harris Street Ultimo NSW 2007 MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS AND SCIENCES Postal address: PO Box K346 Haymarket NSW 1238 Street address: 172 Showground Road Castle Hill NSW 2154 INCORPORATING POWERHOUSE MUSEUM, Administration hours: 9.00 am to 5.00 pm Monday to Friday Postal address: PO Box 8025 Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 Phone (02) 9217 0111 Fax: (02) 9217 0333 Administration hours: 9.00am to 4.00pm Monday to Friday SYDNEY OBSERVATORY, Open 10.00am to 5.00pm every day except Christmas Day Phone: (02) 9762 1300 Fax: (02) 9762 1304 POWERHOUSE DISCOVERY CENTRE School holidays open 9.30am to 5.00pm Email [email protected] Powerhouse Infoline (for information about what’s on) Public Open Days AND NSW MIGRATION HERITAGE CENTRE phone (02) 9217 0444 10.00am to 4.00pm (the second Saturday of each month, Education services bookings and enquiries: except January) phone (02) 9217 0222; fax (02) 9217 0622; TTY (02) 9217 0136; email [email protected] School Holidays 10.00am to 4.00pm Tuesday to Friday Admission charges Available to all general visitors. Bookings not required. Adults $10.00 Child (4 to 15) $5.00 Admission charges Concessions (Australian Pensioners and Seniors cardholders, Adult $8 students, Social Security and Veterans Affairs cardholders) $6.00 Child 4-15 $5 Family groups (2 adults/2 children or 1 adult/3 children) $25.00 Concessions (Australian Pensioners and Senior’s cardholders, Schools (per student) $5.00 students, Social Security and Veterans Affairs cardholders) $5 Powerhouse Members, children under 4 free Family (2 adults/2 children) $25 Members of ICOM, Members of Museums Australia Inc free Powerhouse Members and children under 4 free Group concessions - discounts apply for groups of 10 or more Booked Group Visits Additional admission charges apply to some temporary exhibitions 10.00am - 4.00pm Tuesday to Friday www.powerhousemuseum.com A range of options are available.