Technical Analysis in the Foreign Exchange Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Version: July 6, 2017 MY PAPERS in ECONOMICS: an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Edmar Bacha1

1 This version: July 6, 2017 MY PAPERS IN ECONOMICS: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Edmar Bacha1 1. Introduction Since the mid-1960s, I have written extensively on development economics, the economics of Latin America and Brazil’s economic problems. My papers include essays on persuasion and reflections on economic policy-making experiences. I review these contributions roughly in chronological order not only because of the variety of topics but also because they tend to come together in specific periods. There are seven periods to consider, identified according to my main institutional affiliations: Yale University, 1964- 1968; ODEPLAN, Chile, 1969; IPEA-Rio, 1970-71; University of Brasilia and Harvard University, 1972-1978; PUC-Rio, 1979-1993; Academic research interregnum, 1994-2002; and IEPE/Casa das Garças since 2003. 2. Yale University, 1964-1968 My first published text was originally a term paper for a Master’s level class in international economics at Yale University. In The Strategy of Economic Development, Albert Hirschman suggested that less developed countries would be relatively more efficient at producing goods that required “machine-paced” operations. Carlos Diaz-Alejandro interpreted machine-paced as meaning capital-intensive 1 Founding partner and director of the Casa das Garças Institute of Economic Policy Studies, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. With the usual caveats, I am indebted for comments to André Lara- Resende, Alkimar Moura, Luiz Chrysostomo de Oliveira-Filho, and Roberto Zahga. 2 technologies, and tested the hypothesis that relative labor productivity in a developing country would be higher in more capital-intensive industries. He found some evidence for this. I disagreed with his argument. -

Putting Volatility to Work

Wh o ’ s afraid of volatility? Not anyone who wants a true edge in his or her trad i n g , th a t ’ s for sure. Get a handle on the essential concepts and learn how to improve your trading with pr actical volatility analysis and trading techniques. 2 www.activetradermag.com • April 2001 • ACTIVE TRADER TRADING Strategies BY RAVI KANT JAIN olatility is both the boon and bane of all traders — The result corresponds closely to the percentage price you can’t live with it and you can’t really trade change of the stock. without it. Most of us have an idea of what volatility is. We usually 2. Calculate the average day-to-day changes over a certain thinkV of “choppy” markets and wide price swings when the period. Add together all the changes for a given period (n) and topic of volatility arises. These basic concepts are accurate, but calculate an average for them (Rm): they also lack nuance. Volatility is simply a measure of the degree of price move- Rt ment in a stock, futures contract or any other market. What’s n necessary for traders is to be able to bridge the gap between the Rm = simple concepts mentioned above and the sometimes confus- n ing mathematics often used to define and describe volatility. 3. Find out how far prices vary from the average calculated But by understanding certain volatility measures, any trad- in Step 2. The historical volatility (HV) is the “average vari- er — options or otherwise — can learn to make practical use of ance” from the mean (the “standard deviation”), and is esti- volatility analysis and volatility-based strategies. -

Testing the Profitability of Technical Analysis in Singapore And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS Testing the Profitability of Technical Analysis in Singapore and Malaysian Stock Markets Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Zoheb Jamal HT080461R In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering National University of Singapore 2010 1 Abstract Technical Analysis is a graphical method of looking at the history of price of a stock to deduce the probable future trend in its return. Being primarily visual, this technique of analysis is difficult to quantify as there are numerous definitions mentioned in the literature. Choosing one over the other might lead to data- snooping bias. This thesis attempts to create a universe of technical rules, which are then tested on historical data of Straits Times Index and Kuala Lumpur Composite Index. The technical indicators tested are Filter Rules, Moving Averages, Channel Breakouts, Support and Resistance and Momentum Strategies in Price. The technical chart patterns tested are Head and Shoulders, Inverse Head and Shoulders, Broadening Tops and Bottoms, Triangle Tops and Bottoms, Rectangle Tops and Bottoms, Double Tops and Bottoms. This thesis also outlines a pattern recognition algorithm based on local polynomial regression to identify technical chart patterns that is an improvement over the kernel regression approach developed by Lo, Mamaysky and Wang [4]. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Shuzhi Sam Ge whose invaluable advice and support made this research possible. His mentoring and encouragement motivated me to attempt a project in Financial Engineering, even though I did not have a background in Finance. -

Technical and Fundamental Analysis

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 12-2016 Understanding the Retail Investor: Technical and Fundamental Analysis Ben Davis [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Ben, "Understanding the Retail Investor: Technical and Fundamental Analysis" (2016). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2024 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Tennessee Global Leadership Scholars & Chancellors Honors Program Undergraduate Thesis Understanding the Retail Investor: Technical and Fundamental Analysis Benjamin Craig Davis Advisor: Dr. Daniel Flint April 22, 2016 1 Understanding the Retail Investor: Fundamental and Technical Analysis Abstract: If there is one thing that people take more seriously than their health, it is money. Behavior and emotion influence how retail investors make decisions on the methodology of investing/trading their money. The purpose of this study is to better understand what influences retail investors to choose the method by which they invest in capital markets. By better understanding what influences retail investors to choose a certain investment methodology, eventually researchers can provide tailored and normative advice to investors as well as the financial planning industry in effectively and efficiently working with clients. -

Relative Strength Index for Developing Effective Trading Strategies in Constructing Optimal Portfolio

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 12, Number 19 (2017) pp. 8926-8936 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Relative Strength Index for Developing Effective Trading Strategies in Constructing Optimal Portfolio Dr. Bhargavi. R Associate Professor, School of Computer Science and Software Engineering, VIT University, Chennai, Vandaloor Kelambakkam Road, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0001-8319-6851 Dr. Srinivas Gumparthi Professor, SSN School of Management, Old Mahabalipuram Road, Kalavakkam, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0003-0428-2765 Anith.R Student, SSN School of Management, Old Mahabalipuram Road, Kalavakkam, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. Abstract Keywords: RSI, Trading, Strategies innovation policy, innovative capacity, innovation strategy, competitive Today’s investors’ dilemma is choosing the right stock for advantage, road transport enterprise, benchmarking. investment at right time. There are many technical analysis tools which help choose investors pick the right stock, of which RSI is one of the tools in understand whether stocks are INTRODUCTION overpriced or under priced. Despite its popularity and powerfulness, RSI has been very rarely used by Indian Relative Strength Index investors. One of the important reasons for it is lack of Investment in stock market is common scenario for making knowledge regarding how to use it. So, it is essential to show, capital gains. One of the major concerns of today’s investors how RSI can be used effectively to select shares and hence is regarding choosing the right securities for investment, construct portfolio. Also, it is essential to check the because selection of inappropriate securities may lead to effectiveness and validity of RSI in the context of Indian stock losses being suffered by the investor. -

Stairstops Using Magee’S Basing Points to Ratchet Stops in Trends

StairStops Using Magee’s Basing Points to Ratchet Stops in Trends This may be the most important book on stops of this decade for the general investor. Professor Henry Pruden, PhD. Golden Gate University W.H.C. Bassetti Coauthor/Editor Edwards & Magee’s Technical Analysis of Stock Trends, 9th Edition This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission, and sources are indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable date and information, but the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or for the consequences of their use. Neither this book nor any part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The consent of MaoMao Press LLC does not extend to copying for general distribution, for promotion, for creating new works, or for resale. Specific permission must be obtained in writing from MaoMao Press LLC for such copying. Direct all inquiries to MaoMao Press LLC, POB 88, San Geronimo, CA 94963-0088 Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation, without intent to infringe. Dow–JonesSM, The DowSM, Dow–Jones Industrial AverageSM, and DJIASM are service marks of Dow– Jones & Company, Inc., and have been licensed for use for certain purposes by the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago (CBOT®). -

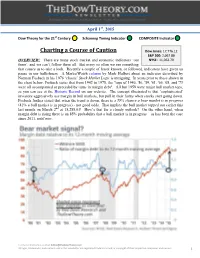

Dow Theory for the 21St Century Schannep Timing Indicator COMPOSITE Indicator

st April 1 , 2015 Dow Theory for the 21st Century Schannep Timing Indicator COMPOSITE Indicator Charting a Course of Caution Dow Jones: 17,776.12 S&P 500: 2,067.88 OVERVIEW: There are many stock market and economic indicators ‘out NYSE: 11,062.79 there’, and we can’t follow them all. But every so often we see something that causes us to take a look. Recently a couple of lesser known, or followed, indicators have given us pause in our bullishness. A MarketWatch column by Mark Hulbert about an indicator described by Norman Fosback in his 1976 ‘classic’ Stock Market Logic is intriguing. In years prior to those shown in the chart below, Fosback states that from 1942 to 1975, the "tops of 1946, '56, '59, '61, '66, '68, and '73 were all accompanied or preceded by turns in margin debt". All but 1959 were major bull market tops, as you can see at the Historic Record on our website. The concept illustrated is that ‘sophisticated’ investors aggressively use margin in bull markets, but pull in their horns when stocks start going down. Fosback further stated that when the trend is down, there is a 59% chance a bear market is in progress (41% a bull market is in progress) - not good odds. That implies the bull market topped out earlier this last month on March 2nd at 18,288.63! How’s that for a cloudy outlook? On the other hand, when margin debt is rising there is an 85% probability that a bull market is in progress – as has been the case since 2011, until now. -

The Conflicting Developments of RMB Internationalization: Contagion

Proceeding Paper The Conflicting Developments of RMB Internationalization: Contagion Effect and Dynamic Conditional Correlation † Xiangqing Lu and Roengchai Tansuchat * Center of Excellence in Econometric, Faculty of Economics, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Presented at the 7th International Conference on Time Series and Forecasting, Gran Canaria, Spain, 19–21 July 2021. Abstract: As the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer, China has made exchange rate stability a top priority for its economic growth. With development over decades, however, China now holds excess dollar reserves that have suffered a huge paper loss because of quantitative easing in the United States. In this reality, China has been provoked into speeding RMB internationalization as a strategy to reduce the cost and get rid of the excessive dependence on the US dollar. Thus, this study attempts to investigate the volatility contagion effect and dynamic conditional correlation among four assets, namely China’s onshore exchange rate (CNY), China’s offshore exchange rate (CNH), China’s foreign exchange reserves (FER), and RMB internationalization level (RGI). Considering the huge changes before and after China’s “8.11” exchange rate reform in 2015, we separate the period of study into two sub-periods. The Diagonal BEKK-GARCH model is employed for this analysis. The results exhibit large GARCH effects and relatively low ARCH effects among all periods and evidence that, before August 2015, there was a weak contagion effect among them. However, after September 2015, the model validates a strengthened volatility contagion within CNY and CNH, CNY and RGI, Citation: Lu, X.; Tansuchat, R. -

British Banks in Brazil During an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930)* Prepared For: European Banks in Latin America During

British Banks in Brazil during an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930)* Prepared for: European Banks in Latin America during the First Age of Globalization, 1870-1914 Session 102 XIV International Economic History Congress Helsinki, 21 August 2006 Gail D. Triner Associate Professor Department of History Rutgers University New Brunswick NJ 08901-1108 USA [email protected] * This paper has benefited from comments received from participants at the International Economic History Association, Buenos Aires (2002), the pre-conference on Doing Business in Latin America, London (2001), the European Association of Banking History, Madrid (1997), the Conference on Latin American History, New York (1997) and the Anglo-Brazilian Business History Conference, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (1997) and comments from Rory Miller. British Banks in Brazil during an Early Era of Globalization (1889-1930) Abstract This paper explores the impact of the British-owned commercial banks that became the Bank of London and South America in the Brazilian financial system and economy during the First Republic (1889-1930) coinciding with the “classical period” of globalization. It also documents the decline of British presence during the period and considers the reasons for the decline. In doing so, it emphasizes that globalization is not a static process. With time, global banking reinforced development in local markets in ways that diminished the original impetus of the global trading system. Increased competition from privately owned banks, both Brazilian and other foreign origins, combined with a static business perspective, had the result that increasing orientation away from British organizations responded more dynamically to the changing economy that banks faced. -

The Renminbi's Ascendance in International Finance

207 The Renminbi’s Ascendance in International Finance Eswar S. Prasad The renminbi is gaining prominence as an international currency that is being used more widely to denominate and settle cross-border trade and financial transactions. Although China’s capital account is not fully open and the exchange rate is not entirely market determined, the renminbi has in practice already become a reserve currency. Many central banks hold modest amounts of renminbi assets in their foreign exchange reserve portfolios, and a number of them have also set up local currency swap arrangements with the People’s Bank of China. However, China’s shallow and volatile financial markets are a major constraint on the renminbi’s prominence in international finance. The renminbi will become a significant reserve currency within the next decade if China continues adopting financial-sector and other market-oriented reforms. Still, the renminbi will not become a safe-haven currency that has the potential to displace the U.S. dollar’s dominance unless economic reforms are accompanied by broader institutional reforms in China. 1. Introduction This paper considers three related but distinct aspects of the role of the ren- minbi in the global monetary system and describes the Chinese government’s actions in each of these areas. First, I discuss changes in the openness of Chi- na’s capital account and the degree of progress towards capital account convert- ibility. Second, I consider the currency’s internationalization, which involves its use in denominating and settling cross-border trades and financial transac- tions—that is, its use as an international medium of exchange. -

Lecture 20: Technical Analysis Steven Skiena

Lecture 20: Technical Analysis Steven Skiena Department of Computer Science State University of New York Stony Brook, NY 11794–4400 http://www.cs.sunysb.edu/∼skiena The Efficient Market Hypothesis The Efficient Market Hypothesis states that the price of a financial asset reflects all available public information available, and responds only to unexpected news. If so, prices are optimal estimates of investment value at all times. If so, it is impossible for investors to predict whether the price will move up or down. There are a variety of slightly different formulations of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). For example, suppose that prices are predictable but the function is too hard to compute efficiently. Implications of the Efficient Market Hypothesis EMH implies it is pointless to try to identify the best stock, but instead focus our efforts in constructing the highest return portfolio for our desired level of risk. EMH implies that technical analysis is meaningless, because past price movements are all public information. EMH’s distinction between public and non-public informa- tion explains why insider trading should be both profitable and illegal. Like any simple model of a complex phenomena, the EMH does not completely explain the behavior of stock prices. However, that it remains debated (although not completely believed) means it is worth our respect. Technical Analysis The term “technical analysis” covers a class of investment strategies analyzing patterns of past behavior for future predictions. Technical analysis of stock prices is based on the following assumptions (Edwards and Magee): • Market value is determined purely by supply and demand • Stock prices tend to move in trends that persist for long periods of time. -

Technical Analysis, Liquidity, and Price Discovery∗

Technical Analysis, Liquidity, and Price Discovery∗ Felix Fritzy Christof Weinhardtz Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Karlsruhe Institute of Technology This version: 27.08.2016 Abstract Academic literature suggests that Technical Analysis (TA) plays a role in the decision making process of some investors. If TA traders act as uninformed noise traders and generate a relevant amount of trading volume, market quality could be affected. We analyze moving average (MA) trading signals as well as support and resistance levels with respect to market quality and price efficiency. For German large-cap stocks we find excess liquidity demand around MA signals and high limit order supply on support and resistance levels. Depending on signal type, spreads increase or remain unaffected which contra- dicts the mitigating effect of uninformed TA trading on adverse selection risks. The analysis of transitory and permanent price components demonstrates increasing pricing errors around TA signals, while for MA permanent price changes tend to increase of a larger magnitude. This suggests that liquidity demand in direction of the signal leads to persistent price deviations. JEL Classification: G12, G14 Keywords: Technical Analysis, Market Microstructure, Noise Trading, Liquidity ∗Financial support from Boerse Stuttgart is gratefully acknowledged. The Stuttgart Stock Exchange (Boerse Stuttgart) kindly provided us with databases. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Boerse Stuttgart Group. yE-mail: [email protected]; Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Research Group Financial Market Innovation, Englerstrasse 14, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany. zE-mail: [email protected]; Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Institute of Information System & Marketing, Englerstrasse 14, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany.