Stampede at the Kumbh Mela: Preventable Accident? 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 01 Nov 21.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Wednesday 21 November 2012 7 Muharram 1434 - Volume 17 Number 5525 Price: QR2 Qtel signs Messi nets two $500m Islamic as Barca reach financing deal last sixteen Business | 17 Sport | 28 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Emir opens new Qapco plant QR319,000 collected QR2.3bn facility can produce 300,000 metric tonnes of LDPE in fines from smokers BY SATISH KANADY DOHA: Long criticised for During the latest anti-tobacco non-existent enforcement of campaign of the SCH, how- DOHA: Reinforcing Qatar’s anti-smoking law, Qatar’s pub- ever, what is surprising is that position as a major petrochemi- lic health authorities have no ‘sheesha’ outlet has been cals producer and exporter, swung into action and handed raided by its inspectors and no the Emir H H Sheikh Hamad out fines to some 829 people so fines have been handed out to bin Khalifa Al Thani launched far this year for lighting up in users to ‘sheesha’ addicts, who, Qatar Petrochemical Company’s public places. understandably, also include an (QAPCO) new state-of-the-art, And the fines the health increasing number of women and third low-density polyethyl- inspectors collected from the children. ene plant (LDPE 3), at a high- violators totalled an impressive The current anti-tobacco law profile ceremony in Mesaieed QR319,000 — which means that is described by anti-smoking Industrial City yesterday. on average a smoker caught paid activists as weak and lacking The opening ceremony was QR385 in fine. -

Discriminatory Treatment of Accident Victims

Discriminatory Treatment of Pravin Bihari Sharan* Accident Victims The subject of this brief article is the discrimination caused by different amounts of compensation in case of accidental death or injury under different existing rules applied to different types of accidents, and, non-existence of specific laws for many other types of accidents like fire. This paper makes out a case for one single law applicable for all kinds of accidents which brings the best practices in computation of compensation and delivery of justice so that the victims of all types of accidents are enabled to rebuild the lives of victims as fast as possible. Keywords: Accident victims, Accident compensation, Tort Law, Fire, MACT, Discrimination Accidents keep happening. Motor accidents are very common, no doubt; but accidents not involving motor vehicles are also not that uncommon. Accidents like fire, building or bridge collapse, stampede, boat capsize, gas leak, industrial accidents, electrocution, etc., too affect thousands every year. It is not easy to forget some of the very tragic accidents from the recent past. • Sixteen people died and nine injured in a five-storey building collapse in Raigad, Maharashtra, on 24th August 2020[1]. • Eleven workmen died inside their workplace in Visakhapatnam when a massive crane crumbled and crashed on to the ground on 1st August 2020[2]. • Eleven persons died and about 1000 got injuries in a gas leak accident in Visakhapatnam on 7th May 2020[3]. • Punjab witnessed a dastardly hooch tragedy which claimed 133 lives in the last week of July 2020[4]. • Sixteen tired migrant workers, sleeping on the railway track, got crushed and killed by a speeding goods train near Aurangabad, Maharashtra on 7th May 2020[5]. -

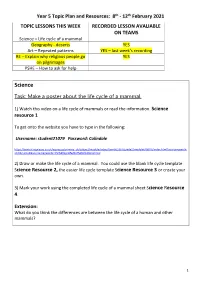

Topic Plan & Resources

Year 5 Topic Plan and Resources: 8th - 12th February 2021 TOPIC LESSONS THIS WEEK RECORDED LESSON AVALIABLE ON TEAMS Science – Life cycle of a mammal Geography - deserts YES Art – Repeated patterns YES – last week’s recording RE – Explain why religious people go YES on pilgrimages PSHE – How to ask for help Science Task: Make a poster about the life cycle of a mammal. 1) Watch this video on a life cycle of mammals or read the information. Science resource 1 To get onto the website you have to type in the following: Username: student21079 Password: Colindale https://central.espresso.co.uk/espresso/primary_uk/subject/module/video/item665367/grade2/module648876/index.html?source=search- all-KS2-all-all&source-keywords=life%20cycle%20of%20a%20mammal 2) Draw or make the life cycle of a mammal. You could use the blank life cycle template Science Resource 2, the easier life cycle template Science Resource 3 or create your own. 3) Mark your work using the completed life cycle of a mammal sheet Science Resource 4. Extension: What do you think the differences are between the life cycle of a human and other mammals? 1 Science Resource 1 – Information about the life cycle of a mammal. Mammal Lift cycles All animals, including humans, have life cycles. Why are mammals different? Mammals are unique in the animal kingdom because they don’t lay eggs. They are the only animal group to give birth to live young. How long do they carry their babies (pregnant)? In humans, it takes about nine months from conception (or fertilisation) before a child is ready to be born. -

MAHA KUMBH MELA 2010 HARIDWAR Kumbh Mela Is the Largest Religious Congregation in the World

MAHA KUMBH MELA 2010 HARIDWAR Kumbh Mela is the largest religious congregation in the world. According to astrologers, the 'Kumbh Fair' takes place when the planet Jupiter enters Aquarius and the Sun enters Aries. The next Maha Kumbh will be held in the northern Indian town of Haridwar on the banks of river Ganges. Millions of Hindus will have their ritual cleansing bath on eleven auspicious days from January till April 2010. The origin of the Kumbh dates back to the time when Amrita Kalasha (pot of nectar of immortality) was recovered from Samudramanthan (during the churning of the primordial sea), for which a tense war between Devtas (Gods) and Asuras (Demons) ensued. To prevent the Amrita Kalasha being forcibly taken into possession by Asuras, who were more powerful than Devtas, its safety was entrusted to the Devtas Brahaspati, Surya, Chandra and Shani. The four Devtas ran away with the Amrita Kalasha to hide it from the Asuras. Learning the conspiracy of Devtas, Asuras turned ferocious and chased the 4 Devtas running with Amrita Kalasha. The chase, lasted 12 days and nights during which the Devtas and Asuras went round the earth and during this chase, Devtas put Amrita Kalasha at Haridwar, Prayag, Ujjain and Nasik. To commemorate this holy event of the Amrita Kalasha being put at 4 places, Kumbh is celebrated every 12 years. Haridwar or “Gateway to God”, the holy city lies at the foot of the Shivalik range of the Himalayas. Legend goes that when lord Shiva sent Ganga to quench the thirst of the people, she extricated herself from the matted locks of Lord Shiva and descended to the plains at Haridwar. -

Learning from India's Kumbh Mela

Annotated Bibliography Learning from India’s Kumbh Mela 2017 Overview This bibliography is an updated revision of a teaching resource originally created as part of the Harvard University collaborative research project, “Contemporary Urbanism: Mapping India’s Kumbh Mela.” The Kumbh Mela is a Hindu ritual and festival that draws millions of pilgrims to the banks of the Ganges River in Allahabad, India, every twelve years, for spiritual purification. More information about the Harvard project is available at http://southasiainstitute.harvard.edu/kumbh-mela. The bibliography includes a curated selection of background readings about the history of the festival, new resources relevant to global health at the Kumbh Mela identified in ongoing literature review, and publications that followed the 2013 Kumbh Mela by Harvard project faculty and researchers (noted with *). Most resources are freely available online. The bibliography is designed as a companion resource for two Global Health Education and Learning Incubator teaching cases: “Toilets and Sanitation at the Kumbh Mela” and “Stampede at the Kumbh Mela: Preventable Accident?” It may also be used in classroom discussions about the study of religion, urbanization in a global world, health governance and governance for health in resource-poor settings, humanitarian aid, and emergency medicine. This bibliography is organized according to the following topics: 1. The Festival: Background and Description Kumbh Mela Festival: General and Historical Sources The Festival as Media Spectacle Harvard University “Mapping the Kumbh Mela: Project” 2. Religious Pilgrimage Religious Pilgrimage and the Kumbh Mela Religious Pilgrimage: General 3. Health Risks and Responses Cholera Water and Sanitation Stampedes and Crowd Management Mass Gatherings and Health: General Resources Environment, Pollution, and India’s Sacred Rivers Health Surveillance Technology 4. -

The Godavari Maha Pushkaram 2015 in Andhra Pradesh State - a Study on Good Practices and Gap Analysis of a Mass Gathering Event

Original Research Article DOI: 10.18231/2394-2738.2017.0014 The Godavari Maha Pushkaram 2015 in Andhra Pradesh State - A study on good practices and gap analysis of a mass gathering event Prabhakar Akurathi1, N. Samson Sanjeeva Rao2,*, TSR Sai3 1PG Student, 2Professor, 3Professor & HOD, NRI Medical College, Chinakakani, Andhra Pradesh *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The Godavari River’s Mahapushkaram observed from 14th to 25th July, 2015 drew upto 10 lakh people to Rajahmundry city and neighboring towns. Due to the flocking of such masses, many problems were anticipated; traffic congestion, poor sanitation, air pollution due to vehicles, water pollution etc. There was also an increased need for proper food, milk and water. An effective mass management plan requires an assessment of the current system’s capacity and understanding of hazards and risks. A review of such events can enlighten us with good practices and identify gaps which can be addressed in future such events. Materials and Method: This qualitative study involved PRA techniques like transect walk on all the days and interaction with key informants and in depth interviews with officials, workers and pilgrims. Preparations made for the Pushkaram, good practices and gaps in the arrangements were observed and noted. The information was transcribed in MS word and identified themes are presented. Results and Discussion: Observations regarding planning, facilities, food and water, sanitation, communication, transport, crowd flow, security and safety revealed many good practices. However many gaps were also identified. On the first day a stampede took place at pushkar ghat with 29 people losing their lives. -

An Analysis of Health Care Services of KUMBH MELA Dr.Vinay Sharma , Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)

Motivation absorbs Magnitude: An analysis of Health Care Services of KUMBH MELA Dr.Vinay Sharma , Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Abstract: This paper highlights the levels of commitment, purposefulness, transparency, efficiency, effective administration and good governance in the delivery of Health Care Services observed and experienced at the largest ever gathering of humans (30 million people on 24th January 2001 on the occasion of Mauni Amavasya) at one sin - gle place of a 3000 acre temporary township since the inception of Human race on our planet Earth. This occasion was KUMBH MELA in the year 2001 wherein 70 million people congregated over a period of few weeks. During this Allahabad (the city where Kumbh was organized) turned into the most densely populated city in the world. (For detailed description of KUMBH and the legend behind please refer to supplementary notes at the end of the paper titled KUMBH MELA a story). The paper tries to analyse the factors behind the successful administration and man - agement of the Health Care Services provided during this period. Though the author himself closely observed the situation by staying there at the location and throughout otherwise wherein he could find the methodology, but an - swers to few questions still remain to be debated and analysed and one of the major question is that what propels peo - ple to manage and execute tasks so precisely despite of the magnitude and high constraints associated with such tasks? The felt and understood answer is ‘Motivation absorbs Magnitude’ but the question is How one gets so much motivated? For example, Dr. -

P8 2 Layout 1

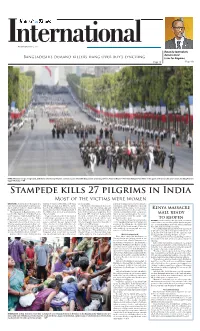

WEDNESDAY, JULY15, 2015 Rwanda lawmakers Bangladeshis demand killers hang over boy’s lynching debate third term for Kagame Page 12 Page 10 PARIS: Mexican troops, foreground, walk down the Champs-Elysees avenue as part of Bastille Day parade yesterday, in Paris, France. Mexico’s President Enrique Pena Nieto is the guest of honor at this year’s event marking France’s biggest holiday. —AP Stampede kills 27 pilgrims in India Most of the victims were women GODAVARI: A stampede on the banks of a number of injured at 40 while confirming known as ghats. public got angry and demanded they be holy river killed at least 27 pilgrims yester- that 27 people had died. While the identi- “The first set of worshippers were com- allowed to enter the ghat too,” Chebolu day in southern India in a tragic beginning ties of all the victims had yet to become ing out of the river after taking a dip and told AFP from the scene. “Some people Kenya massacre to a religious festival season. clear, police and other officials said most of then got in the way of others who wanted started pushing from the back of the The stampede in Rajahmundry, on the the victims were women and included a to be in the water at an auspicious time,” crowd, and that turned into a stampede mall ready border of the twin states of Andhra Pradesh 15-year-old girl. Rao told AFP. However Satyamurthy where people got trampled. The police and Telangana, erupted about two hours Images broadcast on television showed Chebolu, a volunteer for an organisation tried to stop them but the crowd easily after the dawn start of the Maha tearful relatives grieving over lines of bod- that helps run the festival, said the stam- pushed the police away. -

Human Currents: the World's Largest Pilgrimage

WORLD’S LARGEST RECORDED HUMAN GATHERING –TENS OF MILLIONS OF PILGRIMS -- CAPTURED BY PHOTOGRAPHER HANNES SCHMID EXHIBITION PRESENTS IMAGES OF FESTIVAL HELD ONCE EVERY 144 YEARS FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 2011 New York—As many as seventy-five million pilgrims assembled in Allahabad, North India for a month-long Maha Kumbh Mela festival from January to February 2001. It was the largest ever recorded gathering of human beings up to that time, and so immense that the crowd was visible from space. Swiss artist Hannes Schmid was there as Hindu pilgrims moved towards the banks of the sacred Ganges River, capturing this massive pilgrimage with his camera. From July 22 to November 13, 2011 the Rubin Museum of Art will present Schmid’s still and moving images of the festival during Human Currents: The World’s Largest Pilgrimage as Interpreted by Hannes Schmid. The Maha Kumbh Mela—the most important among Kumbh Mela festivals that celebrate gods’ symbolic triumph over demons—is held only once every one hundred forty-four years. Pilgrims mark the festivals by travelling to sites along the banks of the Ganges River, and never more so than during the 2001 Maha Kumbh Mela when a veritable sea of devotees of all ages, castes, and classes traveled from every corner of India to participate. 28 million pilgrims were said to have gathered on the main bathing day alone. “The day, when such a mass of pilgrims of all ages gather for a common purpose and destiny, has intrigued me for as long as I knew,” says photographer Hannes Schmid. -

2 Cops Killed, 1 Critical in Terror-Strike at Court Complex in Kashmir

3 Days’ Forecast Jammu www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather June 11 27.0 39.0 Partly cloudy sky June 12 27.0 40.0 Mainly Clear sky June 13 26.0 40.0 Mainly Clear sky Srinagar June 11 17.0 28.0 Partly cloudy sky June 12 17.0 28.0 Mainly Clear sky June 13 17.0 28.0 Partly cloudy sky Vol No: XXIII Issuethe No. 139 13.06.2018 (Wednesday)northlines Daily Jammu Tawi Price 3/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2017-19 2 cops killed, 1 critical in terror-strike Municipal limits No talks unless India accepts at Court complex in Kashmir of Jammu expand Kashmir as a dispute: Hurriyat NL CORRESPONDENT Kashmir as a dispute". Chak-Rattnoo, Chak- Several new areas SRINAGAR, JUNE 12 In a statement from Jalloo, Kaluchak, Srinagar, APHC 10 soldiers injured in Anantnag Grenade Attack of Deeli, Muthi, Sunjwan, Chowaddi in In a statement, All Parties spokesman GA Gulzar Bahoo Niabat, Similarly, Digiana, Sidra, Hurriyat Conference said the "exemplary in Muthi Niabat Dharmal, CM condemns Bahoo, Gadigarh spokesman GA Gulzar has sacrifices" made by the Muthi, Rakna-Nagbani, said it will be an exercise Kashmiri youth had not included Akalpur, Sangrampur, killing of cops in futility to hold bilateral been offered for any Chalkpatyal, Gangwal, talks unless India political adjustment within NL CORRESPONDENT Thekrik Khanie, Panyal, SRINAGAR, JUNE 12 accepted Kashmir as a the Indian Constitution but JAMMU TAWI, JUNE 12 Pattoli- Berhmna, for the fulfilment of Machallya, Shahzadpur dispute Chief Minister, Mehbooba The Municipal limits of Bubba Ganiya, Chak- Days after responding achieving right to self- Mufti has strongly the Jammu city have been durgoo, Thathar, Barnaie, positively to Home determination. -

Kumbh Mela: What Is the Hindu Festival?

Good Morning Year 3 Big question: Would visiting the Ganges feel special to a Hindu or Non Hindu? Activity 1 Last week we caught a glimpse of a Hindu pilgrimage to the River Ganges. In the video we saw Simran describe her journey from Britain for Kumbh Mela festival. (If you missed it or need to see the video again, click here: https://tinyurl.com/lcp-y3re) Now let’s learn more about the Kumbh Mela festival. Read the text below and answer the questions. Kumbh Mela: What is the Hindu festival? Millions of people will bathe in India's sacred Ganges and Yamuna rivers as part of the Hindu festival of Kumbh Mela. It's the biggest peaceful gathering in the world with over 120 million people expected over the next 49 days. Hindus believe the water from the river will rid them of sin and save them from any future evil. The location of the festival is chosen solely by the position of the sun, moon and Jupiter according to Hindu astrology. 120 million Hindus and tourists will visit the north Indian city of Prayagraj over the next few weeks. The festival is held at Sangam, the point at which India's two mega rivers, the Ganges and Yamuna, come together. The festival moves between the four locations, with Prayagraj being the largest. The other locations are Haridwar, Nashik district, and Ujjain. Kumbh Mela is held every 12 years. Every six years a half Khumb is held. The most recent full Kumbh was held in 2013 in Allahabad and over 100 million people visited. -

Important Festivals in India

Important Fairs of Indian States Fair Venue Place Ambubachi Mela Kamakhya Temple Assam Baneshwar Fair Dungarpur Mahadev Temple Rajasthan Chandrabahaga Fair Jhalarapatan Rajasthan Gangasagar Fair Gangasagar Island West Bengal Madhavpur Mela Porbandar Gujarat Medaram Jatara or Medaram in Warangal Telangana Sammakka Saralamma Jatara Thrissur Pooram Vadakkunnathan Temple in Kerala Thrissur Surajkund Handicrafts Mela Surajkund in Faridabad Haryana Nauchandi Fair Meerut Uttar Pradesh Kumbh Mela Nasik, Ujjain, Nasik, Ujjain, Allahabad, Haridwar Allahabad, Haridwar Pushkar Fair Pushkar Rajasthan Sonepur Cattle Fair Sonepur at the confluence of Bihar Ganga and Gandak Important Festivals in India State Name Festival Name Andhra Pradesh ● Brahmotsavam- It is celebrated at Sri Venkateswara Temple in Tirupati, for 9 days during the months of September to October. ● Bhishma Ekadasi, Deccan Festival, Pitr, Sankranthi, Tyagaraja Festival Arunachal ● Losar Festival- Tibetan New year, Marked with ancient ceremonies that Pradesh represent the struggle between good and evil ● Chalo Loku, Pongtu Assam ● Bohag Bihu- The spring festival of Bohaag Bihu or Rongali Bihu ushers in the New Year in the State of Assam, which marks the onset of a new agricultural cycle. ● Magh or Bhogali Bihu Bihar ● Chhath Puja- Also called Dala Puja devoted to worshiping the sun is traditionally celebrated by the people of Bihar. Chhattisgarh ● Bastar Dussehra - The longest Dussehra celebration in the world is celebrated in Bastar and spans over 75 days starting around August and ending in October. ● Maghi Purnima- It is the flagship festival of this state which encompasses the birth anniversary of Guru Ghasidas. Goa ● Carnival- Three-day non-stop extravaganza of fun, song, music, and dance celebrated just before the 40 days of Lent.