Torts: the Nature of Nuisance, 33 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sniadach, the Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B

Boston College Law Review Volume 14 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 2-1-1973 Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B. McDonnell Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Julian B. McDonnell, Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism?, 14 B.C.L. Rev. 437 (1973), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol14/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SNIADACH, THE REPLEVIN CASES AND SELF-HELP REPOSSESSION-DUE PROCESS TOKENISM? JULIAN B. MCDONNELL* Last term, a divided United States Supreme Court invalidated the replevin statutes of Pennsylvania and Florida. In Fuentes v. Shevinl and Parham v. Cortese' (the Replevin Cases), the Court held these statutes unconstitutional insofar as they authorized repossession of collateral through state officials before the debtor was notified of the attempted repossession and accorded an opportunity to be heard on the merits of the creditor's claim. The Replevin Cases involved typical consumer purchases of household pods,' and accordingly raised new questions about the basic relationship between secured creditors and consumer debtors—a relationship upon which our consumer credit economy is based. Creditors have traditionally regarded the right to immediate repossession of collateral after determining the debtor to be in default as the essence of personal property security arrange- ments,' and their standard-form security agreements typically spell out this right. -

Torts Mnemonics

TORTS MNEMONICS 1) Torts are done IN SIN: I – INTENTIONAL harm to a person (e.g., assault, battery, false imprisonment, or the intentional infliction of emotional harm) N – NEGLIGENT conduct causing personal injury, wrongful death, or prop damage S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL harm to property (e.g., trespass, conversion, or tortious interference with a contract) N – NUISANCE 2) Tortious conduct makes you want to SING: S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL conduct N – NEGLIGENT conduct G – GROSS negligence a/k/a reckless conduct 3) A D’s FIT conduct is unreasonable/negligent when P was within the foreseeable zone of danger: F – FAILURE to take reasonable precautions in light of foreseeable risks I – INADVERTENCE T – THOUGHTLESSNESS 4) To establish a negligence claim, P must mix the right DIP: D – DUTY to exercise reasonable care was owed by the D to the injured P and the D breached this duty (for a negligence claim the duty is always to conform to the legal standard of reasonable conduct in light of the apparent risks) I – Physical INJURY to the P or his property (damages) P – P’s injuries were PROXIMATELY caused by the D’s breach of duty 5) A parent is liable only for the torts of a SICK child: S – in an employment relationship where a child commits a tort, while acting as a SERVANT or agent of the parent I – where the parent entrusts or knowingly leaves in the child’s possession an INSTRUMENTALITY that, in light of the child’s age, intelligence, disposition and prior experience, creates an unreasonable risk of harm to -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 21 Hearing Date: 01/30/19

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 21 HEARING DATE: 01/30/19 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON TRIAL RE-SETTING * TENTATIVE RULING: * Parties to appear. CourtCall is acceptable if there is no argument on line 2. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON DEMURRER TO COMPLAINT FILED BY BAILEY T. LEE, M.D. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The demurrer of defendant Bailey Lee, M.D., to plaintiffs’ complaint is overruled. Defendant shall file and serve his Answer on or before February 13, 2019. Plaintiffs filed this medical malpractice case on September 6, 2016 against defendant Contra Costa County, several physicians, and Does 1-100. Plaintiffs contend they discovered possible liability on the part of Dr. Lee several years after they suit, based upon conversations with an expert consultant. Shortly thereafter, they filed a Doe amendment on September 25, 2018, naming Dr. Lee as Doe 1. Dr. Lee now demurs to the complaint. He argues that the complaint contains no charging allegations against him and that it is uncertain. (CCP § 403.10 (e), (f).) A party who is ignorant of the name of a defendant or the basis for a defendant’s liability may name that defendant by a fictitious name and amend to state the defendant’s true name when the facts are discovered. (CCP § 474; see Breceda v. Gamsby (1968) 267 Cal.App.2d 167, 174.) If section 474 is properly used, no amendment of the complaint is necessary other than the Doe amendment itself. -

I. A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approac

Torts, Sharkey Fall 2006, Dave Fillingame I. INTRODUCTION A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approach B. Holmes: Two theories of common-law liability: 1. Criminalist (Negligence) 2. “A man acts at his own peril” (strict liability) 3. Judge People by an Objective not a Subjective Standard of Care C. Judge v. Jury in Torts II. INTENTIONAL TORTS A. Elements B. Physical Harms 1. Battery a. Eggshell Skull Rule (Vosburg v. Putney) b. Intent to Act v. Intent to Harm c. “Substantial Certainty” Test (Garratt v. Dailey) d. “Playing Piano” (White v. University of Idaho) e. “Transferred” Intent 2. Defenses to Battery: Consent a. Consent b. Consent: Implied License c. Consent to Illegal Acts 3. Defenses to Battery: Insanity 4. Defenses to Battery: Self-Defense and Defense of Others a. Can be used as a defense when innocent bystanders harmed b. Can be used in defense of third-parties c. Must be proportional force 5. Defenses to Battery: Necessity C. Trespass to Land 1. No Damage is Required, Unauthorized Entry on Land is Enough a. An unfounded claim of right does not make a willful entry innocent. b. Quarum Clausum Fregit 2. Use of Deadly Force in Protection of Property a. Posner: We Must Create Incentives to Protect Tulips and Peacocks. b. Use Reasonable Force: Katko v. Briney (Iowa 1971) 3. Defense of Privilege a. Privilege of Necessity b. “General Average Contribution” c. Conditional (Incomplete) Privilege Vincent v. Lake Erie (Minn. 1910) d. The privilege exists only so long as the necessity does. -

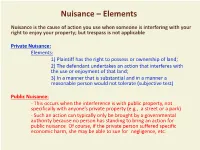

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

South Carolina Damages Second Edition

South Carolina Damages Second Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I DAMAGES IN GENERAL Chapter 1 - DAMAGES IN GENERAL ....................................... 1 A. Necessity of Damages In Actions At Law . 1 1. Actions at Law Versus Actions in Equity . 2 2. Recovery is Premised on the Existence of Damages . 2 3. Restrictions on the Right to Recover Damages . 3 B. Types of Damages and the Purposes They Serve . 4 1. Compensatory Damages ..................................... 4 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 5 3. Punitive Damages .......................................... 6 C. Proof Required for Recovery of Damages . 6 1. Actual Damages............................................ 6 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 9 D. New Trial Nisi, New Trial Absolute, and the Thirteenth Juror . 10 PART II COMPENSATORY DAMAGES Chapter 2 - SOUTH CAROLINA MODIFIED COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE ......... 15 A. Introduction .................................................. 15 B. Contributory Negligence as a Total Bar to Recovery . 16 1. Assumption of the Risk ..................................... 17 2. Last Clear Chance Doctrine ................................. 19 3. Concepts Clouded by the Adoption of Comparative Fault . 19 C. Adoption of Comparative Negligence: Reducing Rather Than Barring Recovery ......................................... 19 1. Apportionment of Responsibility . 20 i Table of Contents 2. Multiple Defendants ....................................... 20 3. Computation of Damages .................................. -

Should Tort Law Protect Property Against Accidental Loss

San Diego Law Review Volume 23 Issue 1 Torts Symposium Article 5 1-1-1986 Should Tort Law Protect Property against Accidental Loss Richard Abel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Richard Abel, Should Tort Law Protect Property against Accidental Loss, 23 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 79 (1986). Available at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol23/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in San Diego Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Should Tort Law Protect Property Against Accidental Loss? RICHARD L. ABEL* Tort damages for accidental harm to property violate the funda- mental values of autonomy, equality, and community. Tort law itself recognizes that property is less important than personal in- tegrity. State action, includingjudicial decisionmaking, that seeks to protect property against inadvertent damage either is unprinci- pled and hence arbitraryor reflects and reinforces the existing dis- tribution of wealth and power, or both. Tort liabilityfor acciden- tal injury to property cannot be defended as a means of reducing secondary accident costs, it entails very high transactioncosts, and it has little or no proven value as a deterrent of careless behavior. Consequently, courts should cease to recognize a cause of action in tort for accidental damage to property. t An earlier version of this Article was presented to the Symposium of the Colston Research Society at the University of Bristol, April 3-6, 1984. -

A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina

South Carolina Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Article 5 Winter 1994 A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina Bradford W. Wyche Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyche, Bradford W. (1994) "A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 45 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol45/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wyche: A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina A GUIDE TO THE COMMON LAW OF NUISANCE IN SOUTH CAROLINA BRADFORD W. WYCHE" INTRODUCTION ........................ ........ 338 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................ ........ 339 THE SPECIAL INJURY RULE ................. ........ 341 PRIVATE NUISANCE ACTIONS: WHAT DOES THE PLAINTIFF HAVE TO PROVE? ......... ...... ........ 347 A. Interest in Land .................. ........ 347 B. Interference ..................... ........ 347 1. Materiality Requirement ........... ........ 347 2. Anticipatory Nuisances ........... ........ 348 3. Surface Waters ................ ........ 349 C. Defendant's Conduct ............... ........ 350 1. Negligence Approach ............ ........ 351 2. Strict Liability Approach .......... ........ 351 3. Restatement Approach ............ ........ 354 -

![[1] the Basics of Property Division](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2246/1-the-basics-of-property-division-1212246.webp)

[1] the Basics of Property Division

RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW FOURTH, PROPERTY PROJECTED OVERALL TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME [1] THE BASICS OF PROPERTY DIVISION ONE: DEFINITIONS Chapter 1. Meanings of “Property” Chapter 2. Property as a Relation Chapter 3. Separation into Things Chapter 4. Things versus Legal Things Chapter 5. Tangible and Intangible Things Chapter 6. Contracts as Property [pointers to Contracts Restatement and UCC] Chapter 7. Property in Information [pointer to Intellectual Property Restatement(s)] Chapter 8. Entitlement and Interest Chapter 9. In Rem Rights Chapter 10. Residual Claims Chapter 11. Customary Rights Chapter 12. Quasi-Property DIVISION TWO: ACCESSION Chapter 13. Scope of Legal Thing Chapter 14. Ad Coelum Chapter 15. Airspace Chapter 16. Minerals Chapter 17. Caves Chapter 18. Accretion, etc. [cross-reference to water law, Vol. 2, Ch. 2] Chapter 19. Fruits, etc. Chapter 20. Fixtures Chapter 21. Increase Chapter 22. Confusion Chapter 23. Improvements DIVISION THREE: POSSESSION Chapter 24. De Facto Possession Chapter 25. Customary Legal Possession Chapter 26. Basic Legal Possession Chapter 27. Rights to Possess Chapter 28. Ownership versus Possession Chapter 29. Transitivity of Rights to Possess Chapter 30. Sequential Possession, Finders Chapter 31. Adverse Possession Chapter 32. Adverse Possession and Prescription Chapter 33. Interests Not Subject to Adverse Possession Chapter 34. State of Mind in Adverse Possession xvii © 2016 by The American Law Institute Preliminary draft - not approved Chapter 35. Tacking in Adverse Possession DIVISION FOUR: ACQUISITION Chapter 36. Acquisition by Possession Chapter 37. Acquisition by Accession Chapter 38. Specification Chapter 39. Creation VOLUME [2] INTERFERENCES WITH, AND LIMITS ON, OWNERSHIP AND POSSESSION Introductory Note (including requirements of possession) DIVISION ONE: PROPERTY TORTS Chapter 1. -

Do Parties to Nuisance Cases Bargain After Judgment? a Glimpse Inside the Cathedral Ward Farnswortht

Do Parties to Nuisance Cases Bargain After Judgment? A Glimpse Inside the Cathedral Ward Farnswortht Economic analysts of remedies often use nuisance cases as examples to illustrate their models. The illustrationscommonly suppose that parties to such cases will be interested in bargainingafter judgment if the court fails to award the rights to the party willing to pay the most for them. ProfessorFarnsworth examines twenty nuisance cases and finds no bar- gaining afterjudgment in any of them; nor did the parties'lawyers believe that bargaining would have occurred ifjudgment had been given to the loser. The lawyers said that the pos- sibility of such bargainingwas foreclosed not by the sorts of transactioncosts that usually are the subject of economic models, but by animosity between the parties and by their dis- taste for cash bargainingover the rights at issue. ProfessorFarnsworth suggests that these results raise a number of interesting questions, such as how the obstacles to bargainingin these cases might be related to the absence of markets for the rights at stake, whether ani- mosity or a distaste for bargainingshould be considered transactioncosts, and whether greaterparticularity might be needed before economic models can generate advice about remedies reliable enough to be useful to courts. INTRODUCTION For about as long as there has been economic analysis of law, there has been speculation about nuisance cases and the possi- bility that parties to them might bargain after judgment. Ronald Coase used nuisance cases to illustrate his argument in The Prob- lem of Social Cost,' and Calabresi and Melamed's famous article on property rights and liability rules likewise used nuisance cases to illustrate the nature of those remedies and when each of them might be appropriate.2 Those articles in turn have spawned a vast literature comparing the consequences of using property rights and liability rules to protect entitlements. -

AGREEMENT for Nuisance Vegetation and Debris Removal from Creeks and Waterways

AGREEMENT FOR Nuisance Vegetation and Debris Removal From Creeks and Waterways THIS AGREEMENT ("Agreement") is made and entered into as of the date of execution by both parties, by and between Lee County, a political subdivision of the State of Florida, hereinafter referred to as the "County" and A+ Environmental Restoration, LLC, a Florida limited liability company, whose address is 2731 SW CR 661, Arcadia, FL 34266, and whose Federal tax identification number is 81- 0876194, hereinafter referred to as "Contractor." WITNESSETH WHEREAS, the County intends to purchase services related to Nuisance Vegetation and Debris Removal From Creeks and Waterways from the Contractor for specific projects as determined by the County (the "Purchase"); and, WHEREAS, the County issued a solicitation, Request for Proposal No. RFP180095MRH on January 16, 2018 (the "Solicitation"); and, WHEREAS, the County evaluated the responses received and found the Contractor qualified to provide the necessary products and services; and, WHEREAS, the County posted a Notice of Intended Decision Proposal Action on April 6, 2018; and, WHEREAS, the Contractor is one of a pool of firms approved to provide services for the Purchase, the County shall award projects as needed, and the Contractor understands and agrees that no work is guaranteed under this Agreement; and, WHEREAS, the Contractor has reviewed the services to be supplied pursuant to this Agreement and is qualified, willing and able to provide all such products and services in accordance with its terms. NOW, THEREFORE, the County and the Contractor, in consideration of the mutual covenants contained herein, do agree as follows: I. PRODUCTS AND SERVICES A. -

Minnesota's Public and Private Nuisance Laws

INFORMATION BRIEF Research Department Minnesota House of Representatives 600 State Office Building St. Paul, MN 55155 Mary Mullen, Legislative Analyst 651-296-9253 Updated: July 2015 Minnesota’s Public and Private Nuisance Laws This information brief describes Minnesota laws that provide remedies to combat offensive or injurious conditions or activities that are a “nuisance” to the surrounding community. A condition or activity may be either a “public nuisance” or a “private nuisance” depending on the scope of the problems caused by the nuisance and on whether it is challenged by a public agency or a private individual. Contents Page State Public Nuisance Law .............................................................................. 2 Local Public Nuisance Laws ............................................................................ 9 Private Nuisance Actions ............................................................................... 11 Copies of this publication may be obtained by calling 651-296-6753. This document can be made available in alternative formats for people with disabilities by calling 651-296-6753 or the Minnesota State Relay Service at 711 or 1-800-627-3529 (TTY). Many House Research Department publications are also available on the Internet at: www.house.mn/hrd/ House Research Department Updated: July 2015 Minnesota’s Public and Private Nuisance Laws Page 2 A “nuisance” is an activity that, in one way or another, affects the right of an individual to enjoy the use of a specified property. Generally speaking, the law recognizes two distinct types of nuisance. A “public nuisance” is an activity (or a failure to act in some cases) that unreasonably interferes or obstructs a right that is conferred on the general public, such as the enjoyment of a public park or other public space.