Ugandan Children and the Atrocities of the Lord's Resistance Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Lord's Resistance Army

Lord’s Resistance Army Key Terms and People People Acana, Rwot David Onen: The paramount chief of the Acholi people, an ethnic group from northern Uganda and southern Sudan, and one of the primary targets of LRA violence in northern Uganda. Bigombe, Betty: Former Uganda government minister and a chief mediator in peace negotiations between the Ugandan government and the LRA in 2004-2005. Chissano, Joaquim: Appointed as Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General to Northern Uganda and Southern Sudan in 2006; now that the internationally-mediated negotiations Joseph Kony, “ultimate commander” of the with the LRA have stalled, Chissano’s role as Special Envoy in the process is unclear. Lord’s Resistance Army/ photo courtesy of Radio France International, taken in the spring of 2008 during the failed Juba Kabila, Joseph: President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Peace Talks. Kony, Joseph: Leader of the LRA. Kony is a self-proclaimed messiah who led the brutal, mystical LRA movement in its rebellion against the Ugandan gov- ernment for over two decades. A war criminal wanted by the International Criminal Court, Kony remains the “ultimate commander” of the LRA, and he determines who lives and dies within the rebel group as they continue their predations today throughout central Africa. Lakwena, Alice Auma: Leader of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, a northern based rebel group that fought against the Ugandan government in the late 1980s. Some of the followers of this movement were later recruited into the LRA by Joseph Kony. Lukwiya, Raska: One of the LRA commanders indicted by the ICC in 2005. -

Page 1 of 76 Uganda 03/10/2004

Uganda Page 1 of 76 THE SCARS OF DEATH Children Abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda Human Rights Watch / Africa Human Rights Watch Children's Rights Project Human Rights Watch New York · Washington · London · Brussels Copyright © September 1997 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-221-1 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 97-74724 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is based on research in Uganda from late May to early June of 1997. The research was conducted by Rosa Ehrenreich, a consultant for the Human Rights Watch Children's Rights Project, and by Yodon Thonden, counsel for the Children's Rights Project. The report was written by Rosa Ehrenreich, and edited by Yodon Thonden and Lois Whitman, the director of the Children's Rights Project. Peter Takirambudde, the director of Human Rights Watch's Africa Division, and Joanne Mariner, associate counsel for Human Rights Watch, provided additional comments on the manuscript. Linda Shipley, associate to the Children's Rights Project, provided invaluable production assistance. This report would not have been possible without the assistance of the UNICEF office in Uganda. In particular, we wish to thank Kathleen Cravero, Ponsiano Ochero, Leila Pakkala, and Keith Wright in Kampala, and George Ogol and Moses Ongaria in Gulu. We are also grateful to Professor Semakula Kiwanuka, the Ugandan permanent representative to the United Nations, and to the many Ugandan government officials who facilitated our mission, including Lieutenant Bantariza Shaban, the public relations liasion officer for the Fourth Division of the Uganda People's Defense Force (UPDF), Colonel James Kazini, Commander of the UPDF Fourth Division, and J.J. -

Atiak Town Board Proposed Physical Development Plan to Nimule Border Tiak T.I a Rls a Gi Onic St.M

400500.000000 40140010.0000000 401500.000000 40240020.0000000 402500.000000 40340030.0000000 403500.000000 4040040.0000000 404500.000000 ATIAK TOWN BOARD ATIAK TOWN BOARD PROPOSED PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN TO NIMULE BORDER TIAK T.I A RLS A GI ONIC ST.M K IA 2012-2022 T A II .C H L A N IO T A N Legend R E T IN LOCAL CENTER R E H T O PLANNING AREA BOUNDARY M LOCAL DISTRIBUTOR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . LDR . 0 0 0 0 SECONDARY ROAD 3 3 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 3 3 6 6 3 3 LDR CONTOURS SECONDARY RING ROAD MDR PROPOSED LAND USES PRIMARY ROAD U LC R B A N STREAM A HDR G HIGH DENSITY RESIDENTIAL R IC MDR U L T U MDR R MEDIUM DENSITY RESIDENTIAL E LDR LOW DENSITY RESIDENTIAL 0 0 0 0 0 URBAN AGRICULTURE 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 HDR MDR 0 5 5 2 2 INSTITUTIONAL 6 6 3 3 LAND FILL P.TI PROPOSED TERTIARY INSTITUTION P.SS PROPOSED SECONDARY SCHOOL P.PS PROPOSED PRIMARY SCHOOL L O C CIVIC A L C E N T E R PB POLICE BARRACKS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 COM 0 2 2 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 2 PRISON LAND 6 6 3 3 INDUSTRIAL WPS WATER PUMPING STATION URBAN AGRICULTURE MDR COM COMMERCIAL WATER RESERVOIR LDR HOTEL ZONE WR MDR MARKET INDUSTRIAL S AL S. -

Conflict's Children: the Human Cost of Small Arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda a Case Study

Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda A case study January 2001 Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda Table of Contents Maps of Uganda and of administrative boundaries of Kitgum and Kotido Districts Methodology, constraints, and a note about the researchers 1/ Executive Summary 2/ Proliferation of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido Districts Background General situation Types and sources of small arms 3/ Impact on general population Displacements Deaths/injuries Abductions and returnees Other violations of human rights 4/ Impact on vulnerable groups Children Women and men Young people and elderly people 5/ Impact on the social sector Education Health 6/ Other impacts Food supplies The balance of power 7/ Conclusion Appendix 1 Selected information on Kotido and Kitgum Districts Appendix 2 Selected socio-economic indicators for Kotido and Kitgum Districts Appendix 3 Selected testimonies on violations of human rights by LRA, Boo-Kec, UPDF, and cattle rustlers Appendix 4 Questionnaire on the impact of small arms on the population in Kitgum and Kotido Districts, January 2001 Appendix 5 List of the interviewees from Kitgim and Kotido Cover photograph: Geoff Sayer/Oxfam 1 Conflict’s Children: the human cost of small arms in Kitgum and Kotido, Uganda Abbreviations AAA Agro-action Allemande (Welthungershilfe) AFDL Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo ALTI Aide aux Lépreux et Tuberculeux de l’Ituri APC Armée du Peuple Congolaise CAC Communauté -

Political Environment Surrounding the Land Conflict in Amuru District Acholi Sub-Region

POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE LAND CONFLICT IN AMURU DISTRICT ACHOLI SUB-REGION Muganzi Edson Rusetuka Journal of Public Policy and Administration ISSN 2520-5315 (Online) Vol 4, Issue 2, No.1, pp 1 - 13, 2019 www.iprjb.org POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE LAND CONFLICT IN AMURU DISTRICT ACHOLI SUB-REGION 1*Muganzi Edson Rusetuka Post Graduate Student: University for Peace *Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] Abstract Purpose: To examine the political environment surrounding the land conflict in Amuru district Acholi sub-region. Methodology: The study employed a descriptive research design involving both qualitative and quantitative studies where 5 focus group discussions with 40 women and 40 men from Pabbo, Amuru and Lamogi sub counties of Amuru district and key interviews with 4 participants from Area Land Committee members and other leaders in the above sub counties. Findings: The findings indicate that over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. Ethnic based land tensions fostered insecurity and instability in the Amuru as people could not walk around freely, access their gardens, were displaced and this in turn affected their ability to make a living through accessing the land. I also found that many women had relational access to land through their marriage and relationship with male kin and this seemed to give them fragile land rights. Men on the other hand had firm control over land and made final decisions relating to sales and land use. -

The Legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bridges, Sarah; Scott, Douglas Working Paper Early childhood health during conflict: The legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda CREDIT Research Paper, No. 19/11 Provided in Cooperation with: The University of Nottingham, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT) Suggested Citation: Bridges, Sarah; Scott, Douglas (2019) : Early childhood health during conflict: The legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda, CREDIT Research Paper, No. 19/11, The University of Nottingham, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT), Nottingham This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/210862 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-Region

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-region Final Report - March 2013 Research conducted under the United Nations Peacebuilding Programme in Uganda by Human Rights Focus EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In a context of land disputes as a potential major conflict driver, the UN Peacebuilding Programme (PBP) commissioned Human Rights Focus (HURIFO) to develop a tool to monitor and map land disputes throughout Acholi. The overall purpose of this project is to obtain and analyse data that enhance understanding of land disputes, and through this to inform policy, advocacy, and other relevant interventions on land rights, security, and access in the sub-region. Two rounds of quantitative data collection have been undertaken comprehensively across the sub-region, in February/March and September/October 2012, along with further qualitative work and analysis of relevant literature. In order to maximise its contribution to urgently needed understanding of land disputes in Acholi, the project has sought to map and collect data not simply on the numbers and types of land disputes, but also on the substrata: the nature of the landholdings on which disputes are taking place; how land is used and controlled, and by whom. KEY FINDINGS • Over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. • The overall number of discrete rural land disputes is declining significantly. Findings suggest that disputes are being resolved at a rate of about 50% over a six-month period. First-round research indicated that total land disputes between September/ October 2011 and February/March 2012 numbered about 4,300; second-round data identified just over 2,100 total disputes over the period between April and August/ September 2012. -

Northern Uganda Land Study Analysis of Post Conflict

NORTHERN UGANDA LAND STUDY ANALYSIS OF POST CONFLICT LAND POLICY AND LAND ADMINISTRATION: A SURVEY OF IDP RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT ISSUES AND LESSON: ACHOLI AND LANGO REGIONS By : Team Members: Margaret A. Rugadya (Lead Consultant) Eddie Nsamba-Gayiiya Herbert Kamusiime World Bank UPI: 267367 Consultant Surveyors and Associates for Associates for Development Planners Development Tel. +414-541988, +0772-497145, Kampala Kampala +0712-497145 Email: [email protected] February, 2008 For the World Bank, to input into Northern Uganda Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) and the Draft National Land Policy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the second in a series of land studies for northern Uganda, whose core objective is to inform the Plan for Recovery and Development of Northern Uganda (PRDP) and the National Land Policy. It builds on the work of the first phase conducted in Teso region to present a more quantitative analysis of trends on disputes and claims on land before displacement, during displacement and emerging trends or occurrences on return for Acholi and Lango sub-regions. The key findings in the Teso study are that there is a high level of distrust towards the Central Government’s intentions toward land; customary tenure has evolved and adapted to changing circumstances but remains to be seen as a legitimate form of tenure; there was not a high prevalence of land disputes; the statutory and customary institutional framework for land administration and justice has been severely weakened; and vulnerable groups such as women and children have been marginalized during the return process. However, the Teso region has been one of the most secure regions during the conflict and has experienced very short periods of displacement and as such does not provide a good marker for the situation in the rest of northern Uganda. -

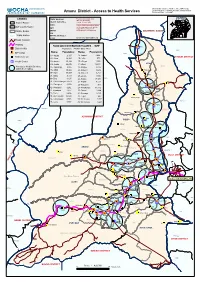

Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007

District, Sub counties, Heath centres,IDP Camps, Settlement sites, Tranpsort Network & Water bodies Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007 UGANDA LEGEND Data Sources Prepared and compiled by IMU OCHA-Uganda N District Border DDisatrticat SAuothuorrictiess Printed: 07 June 2006 _____________________________ W E AMURU NUDC The boundaries and names shown Sub County Border on this map approximate and do S WFP imply official endorsement/ Parish Border UNHCR acceptance by United Nations. SOUTHERN SUDAN IOM Kampala Water Bodies WHO/Health Cluster OCHA Email: [email protected] Road Network Railway FOOD AID DISTRIBUTION FIGURES - WFP Bibia [% District H/Qs Population: 288,062 (May 2007) PÆ OGILI Name: Population: Name: Population: IDP Camp DZAIPI Bibia 01- Agung 2,197 18- LanAgDoROl PI 3,422 Settlement site KITGUM DISTRICT 02- Alero 12,399 19- Lolim 573 PÆ Health Centre 03- Amuru 35,134 20- Olinga 1,565 ATIAK 04- Anaka 20,676 21- OlwaADl JUMAN TC 16,628 CIFORO Okidi Access to Health Services 05- Aparanga 2,955 22- Olwiyo 2,616 Pacilo within 5 km radius. 06- Atiak 19,980 23- Omee I 4,629 Abalokodi 07- Awer 14,997 24- Omee II 3,253 Pacilo 08- Bibia 5,133 25- Otong 1,572 09- Bira 3,105 26- Pabbo 47,173 PAKELLE Parwacha NOMANS 10- Corner Nwoya 5,279 27- Pagak 9,577 Okidi 11- Guruguru 3,360 Kal 28- Palukere 911 Atiak 12- Jeng-gari 4,292 29- Parabongo 13,672 PÆ OFUA 13- Kaladima 1,817 30- Pawel 3,884 Pupwonya 14- Keyo 6,606 31- Purongo 8,141 Palukere 15- Koch Goma 13,324 32- Tegot 442 Olamnyungo Palukere 16- Labongogali -

Northern Uganda

United Nations s/2006/29 Security Council Distr.: General 19 January 2006 Original: English Letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Reference is made to the letter dated 5 January 2006 from the Permanent Representative of Canada to the United Nations addressed to you (S/2006/13). On instructions from my Government, I have the honour to forward to you herewith a letter from the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Uganda transmitting an official position paper of the Government of Uganda on the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see annex). The Government of Uganda is giving a factual account of what is happening in northern Uganda and what the Government of Uganda is doing to address the situation on the ground. Any call for the situation in northern Uganda to be put on the agenda of the Security Council is therefore unjustified. I would be grateful if the present letter and its annex were circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Catherine Otiti Charge d’affaires a.i. 00-?1473 I: 240106 ,111 lllllll.ililII 111111 II Annex to the letter dated 16 January 2006 from the Charge d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Uganda to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Attached is a synopsis of the humanitarian situation in northern Uganda (see appendix). It gives a historical background of the problem of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the ensuing humanitarian situation. -

Regional Development for Amuru and Nwoya Districts

PART 1: RURAL ROAD MASTER PLANNIN G IN AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS SECTION 2: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS Project for Rural Road Network Planning in Northern Uganda Final Report Vol.2: Main Report 3. PRESENT SITUATION OF AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS 3.1 Natural Conditions (1) Location Amuru and Nwoya Districts are located in northern Uganda. These districts are bordered by Sudan in the north and eight Ugandan Districts on the other sides (Gulu, Lamwo, Adjumani, Arua, Nebbi, Bulisa, Masindi and Oyam). (2) Land Area The total land area of Amuru and Nwoya Districts is about 9,022 sq. km which is 3.7 % of that of Uganda. It is relatively difficult for the local government to administer this vast area of the district. (3) Rivers The Albert Nile flows along the western border of these districts and the Victoria Nile flows along their southern borders as shown in Figure 3.1.2. Within Amuru and Nwoya Districts, there are six major rivers, namely the Unyama River, the Ayugi River, the Omee River, the Aswa River, Tangi River and the Ayago River. These rivers are major obstacles to movement of people and goods, especially during the rainy season. (4) Altitude The altitude ranges between 600 and 1,200 m above sea level. The altitude of the south- western area that is a part of Western Rift Valley is relatively low and ranges between 600 and 800 m above sea level. Many wild animals live near the Albert Nile in the western part of Amuru and Nwoya Districts and near the Victoria Nile in the southern part of Nwoya District because of a favourable climate.