MASTER of ARTS in CONFLICT ANALYSIS and MANAGEMENT We Accept This Thesis As Conforming to the Required Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Atiak Town Board Proposed Physical Development Plan to Nimule Border Tiak T.I a Rls a Gi Onic St.M

400500.000000 40140010.0000000 401500.000000 40240020.0000000 402500.000000 40340030.0000000 403500.000000 4040040.0000000 404500.000000 ATIAK TOWN BOARD ATIAK TOWN BOARD PROPOSED PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN TO NIMULE BORDER TIAK T.I A RLS A GI ONIC ST.M K IA 2012-2022 T A II .C H L A N IO T A N Legend R E T IN LOCAL CENTER R E H T O PLANNING AREA BOUNDARY M LOCAL DISTRIBUTOR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . LDR . 0 0 0 0 SECONDARY ROAD 3 3 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 3 3 6 6 3 3 LDR CONTOURS SECONDARY RING ROAD MDR PROPOSED LAND USES PRIMARY ROAD U LC R B A N STREAM A HDR G HIGH DENSITY RESIDENTIAL R IC MDR U L T U MDR R MEDIUM DENSITY RESIDENTIAL E LDR LOW DENSITY RESIDENTIAL 0 0 0 0 0 URBAN AGRICULTURE 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 HDR MDR 0 5 5 2 2 INSTITUTIONAL 6 6 3 3 LAND FILL P.TI PROPOSED TERTIARY INSTITUTION P.SS PROPOSED SECONDARY SCHOOL P.PS PROPOSED PRIMARY SCHOOL L O C CIVIC A L C E N T E R PB POLICE BARRACKS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 COM 0 2 2 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 2 PRISON LAND 6 6 3 3 INDUSTRIAL WPS WATER PUMPING STATION URBAN AGRICULTURE MDR COM COMMERCIAL WATER RESERVOIR LDR HOTEL ZONE WR MDR MARKET INDUSTRIAL S AL S. -

Political Environment Surrounding the Land Conflict in Amuru District Acholi Sub-Region

POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE LAND CONFLICT IN AMURU DISTRICT ACHOLI SUB-REGION Muganzi Edson Rusetuka Journal of Public Policy and Administration ISSN 2520-5315 (Online) Vol 4, Issue 2, No.1, pp 1 - 13, 2019 www.iprjb.org POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE LAND CONFLICT IN AMURU DISTRICT ACHOLI SUB-REGION 1*Muganzi Edson Rusetuka Post Graduate Student: University for Peace *Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] Abstract Purpose: To examine the political environment surrounding the land conflict in Amuru district Acholi sub-region. Methodology: The study employed a descriptive research design involving both qualitative and quantitative studies where 5 focus group discussions with 40 women and 40 men from Pabbo, Amuru and Lamogi sub counties of Amuru district and key interviews with 4 participants from Area Land Committee members and other leaders in the above sub counties. Findings: The findings indicate that over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. Ethnic based land tensions fostered insecurity and instability in the Amuru as people could not walk around freely, access their gardens, were displaced and this in turn affected their ability to make a living through accessing the land. I also found that many women had relational access to land through their marriage and relationship with male kin and this seemed to give them fragile land rights. Men on the other hand had firm control over land and made final decisions relating to sales and land use. -

The Legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bridges, Sarah; Scott, Douglas Working Paper Early childhood health during conflict: The legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda CREDIT Research Paper, No. 19/11 Provided in Cooperation with: The University of Nottingham, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT) Suggested Citation: Bridges, Sarah; Scott, Douglas (2019) : Early childhood health during conflict: The legacy of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda, CREDIT Research Paper, No. 19/11, The University of Nottingham, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT), Nottingham This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/210862 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-Region

LAND CONFLICT MONITORING and MAPPING TOOL for the Acholi Sub-region Final Report - March 2013 Research conducted under the United Nations Peacebuilding Programme in Uganda by Human Rights Focus EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In a context of land disputes as a potential major conflict driver, the UN Peacebuilding Programme (PBP) commissioned Human Rights Focus (HURIFO) to develop a tool to monitor and map land disputes throughout Acholi. The overall purpose of this project is to obtain and analyse data that enhance understanding of land disputes, and through this to inform policy, advocacy, and other relevant interventions on land rights, security, and access in the sub-region. Two rounds of quantitative data collection have been undertaken comprehensively across the sub-region, in February/March and September/October 2012, along with further qualitative work and analysis of relevant literature. In order to maximise its contribution to urgently needed understanding of land disputes in Acholi, the project has sought to map and collect data not simply on the numbers and types of land disputes, but also on the substrata: the nature of the landholdings on which disputes are taking place; how land is used and controlled, and by whom. KEY FINDINGS • Over 90% of rural land is understood by the people who live there as under communal control/ownership. These communal land owners are variously understood as clans, sub-clans or extended families. • The overall number of discrete rural land disputes is declining significantly. Findings suggest that disputes are being resolved at a rate of about 50% over a six-month period. First-round research indicated that total land disputes between September/ October 2011 and February/March 2012 numbered about 4,300; second-round data identified just over 2,100 total disputes over the period between April and August/ September 2012. -

Northern Uganda Land Study Analysis of Post Conflict

NORTHERN UGANDA LAND STUDY ANALYSIS OF POST CONFLICT LAND POLICY AND LAND ADMINISTRATION: A SURVEY OF IDP RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT ISSUES AND LESSON: ACHOLI AND LANGO REGIONS By : Team Members: Margaret A. Rugadya (Lead Consultant) Eddie Nsamba-Gayiiya Herbert Kamusiime World Bank UPI: 267367 Consultant Surveyors and Associates for Associates for Development Planners Development Tel. +414-541988, +0772-497145, Kampala Kampala +0712-497145 Email: [email protected] February, 2008 For the World Bank, to input into Northern Uganda Peace, Recovery and Development Plan (PRDP) and the Draft National Land Policy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the second in a series of land studies for northern Uganda, whose core objective is to inform the Plan for Recovery and Development of Northern Uganda (PRDP) and the National Land Policy. It builds on the work of the first phase conducted in Teso region to present a more quantitative analysis of trends on disputes and claims on land before displacement, during displacement and emerging trends or occurrences on return for Acholi and Lango sub-regions. The key findings in the Teso study are that there is a high level of distrust towards the Central Government’s intentions toward land; customary tenure has evolved and adapted to changing circumstances but remains to be seen as a legitimate form of tenure; there was not a high prevalence of land disputes; the statutory and customary institutional framework for land administration and justice has been severely weakened; and vulnerable groups such as women and children have been marginalized during the return process. However, the Teso region has been one of the most secure regions during the conflict and has experienced very short periods of displacement and as such does not provide a good marker for the situation in the rest of northern Uganda. -

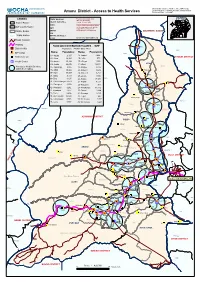

Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007

District, Sub counties, Heath centres,IDP Camps, Settlement sites, Tranpsort Network & Water bodies Amuru District - Access to Health Services Reference Date: June 2007 UGANDA LEGEND Data Sources Prepared and compiled by IMU OCHA-Uganda N District Border DDisatrticat SAuothuorrictiess Printed: 07 June 2006 _____________________________ W E AMURU NUDC The boundaries and names shown Sub County Border on this map approximate and do S WFP imply official endorsement/ Parish Border UNHCR acceptance by United Nations. SOUTHERN SUDAN IOM Kampala Water Bodies WHO/Health Cluster OCHA Email: [email protected] Road Network Railway FOOD AID DISTRIBUTION FIGURES - WFP Bibia [% District H/Qs Population: 288,062 (May 2007) PÆ OGILI Name: Population: Name: Population: IDP Camp DZAIPI Bibia 01- Agung 2,197 18- LanAgDoROl PI 3,422 Settlement site KITGUM DISTRICT 02- Alero 12,399 19- Lolim 573 PÆ Health Centre 03- Amuru 35,134 20- Olinga 1,565 ATIAK 04- Anaka 20,676 21- OlwaADl JUMAN TC 16,628 CIFORO Okidi Access to Health Services 05- Aparanga 2,955 22- Olwiyo 2,616 Pacilo within 5 km radius. 06- Atiak 19,980 23- Omee I 4,629 Abalokodi 07- Awer 14,997 24- Omee II 3,253 Pacilo 08- Bibia 5,133 25- Otong 1,572 09- Bira 3,105 26- Pabbo 47,173 PAKELLE Parwacha NOMANS 10- Corner Nwoya 5,279 27- Pagak 9,577 Okidi 11- Guruguru 3,360 Kal 28- Palukere 911 Atiak 12- Jeng-gari 4,292 29- Parabongo 13,672 PÆ OFUA 13- Kaladima 1,817 30- Pawel 3,884 Pupwonya 14- Keyo 6,606 31- Purongo 8,141 Palukere 15- Koch Goma 13,324 32- Tegot 442 Olamnyungo Palukere 16- Labongogali -

Ugandan Children and the Atrocities of the Lord's Resistance Army

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 1998 The Stories We Must Tell: Ugandan Children and the Atrocities of the Lord's Resistance Army Rosa Brooks Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1260 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2312704 45 Africa Today 79-102 (1998) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Africa Today 45, 1 (1998}, 79-102 Africa Rights Monitor The Stories We Must Tell: Ugandan Children and the Atrocities of the Lord's Resistance Army Rosa Ehrenreich ROUX springs forward and places himself before the marchers, his back to them, still with fettered arms. When will you learn to see When will you learn to take sidesl During the summer of 1997, I spent a short time in Uganda as a consultant for Human Rights Watch, interviewing children who had been abducted by a rebel group called the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) and who had expe rienced almost unimaginable horror.2 Adjectives cannot convey the reality best associated with images of the Cambodian genocide, the Jewish Holocaust, and recent events in Bosnia/Herzegovina. Like the Khmer Rouge, the Nazis, and Radovan Karadzic's Bosnian Serb militia, the LRA employs a calculated brutality against northern Ugandan civilians, forcing them tci participate in atrocities against fellow citizens. -

Regional Development for Amuru and Nwoya Districts

PART 1: RURAL ROAD MASTER PLANNIN G IN AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS SECTION 2: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS Project for Rural Road Network Planning in Northern Uganda Final Report Vol.2: Main Report 3. PRESENT SITUATION OF AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS 3.1 Natural Conditions (1) Location Amuru and Nwoya Districts are located in northern Uganda. These districts are bordered by Sudan in the north and eight Ugandan Districts on the other sides (Gulu, Lamwo, Adjumani, Arua, Nebbi, Bulisa, Masindi and Oyam). (2) Land Area The total land area of Amuru and Nwoya Districts is about 9,022 sq. km which is 3.7 % of that of Uganda. It is relatively difficult for the local government to administer this vast area of the district. (3) Rivers The Albert Nile flows along the western border of these districts and the Victoria Nile flows along their southern borders as shown in Figure 3.1.2. Within Amuru and Nwoya Districts, there are six major rivers, namely the Unyama River, the Ayugi River, the Omee River, the Aswa River, Tangi River and the Ayago River. These rivers are major obstacles to movement of people and goods, especially during the rainy season. (4) Altitude The altitude ranges between 600 and 1,200 m above sea level. The altitude of the south- western area that is a part of Western Rift Valley is relatively low and ranges between 600 and 800 m above sea level. Many wild animals live near the Albert Nile in the western part of Amuru and Nwoya Districts and near the Victoria Nile in the southern part of Nwoya District because of a favourable climate. -

10. Present Situation of Road Traffic and Transport in Amuru and Nwoya Districts

Project for Rural Road Network Planning in Northern Uganda Final Report Vol.2: Main Report 10. PRESENT SITUATION OF ROAD TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT IN AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS 10.1 Road Traffic Condition in Acholi Sub-region 10.1.1 Traffic Survey (1) Outline of the Survey A Traffic Survey was conducted to grasp the baseline traffic information, e.g., traffic volume and OD (origin and destination) along the main trunk road and district roads, in order to understand the current traffic flow and carry out the demand forecast analysis. (2) Survey Method and Survey Location The Traffic Survey was conducted, covering Acholi Sub-region, at 15 locations mainly located along the national roads at the provincial boundaries and cross border points and at 50 locations mainly located along the national and district roads. At the 15 locations, both 12-hour traffic count and OD interview surveys were carried out. At the 50 locations, only 6-hour traffic count surveys were carried out. The Traffic Survey is summarized in Table 10.1.1. Table 10.1.1 Summary of Traffic Survey Survey Period Survey Survey Name Survey Time [Date] Location (1) 12-hour Traffic Count 1 weekday 12 hours (6:00 - 18:00) 15 locations Survey [9/21/2009 – 10/2/2009] (2) Roadside OD Interview 1 weekday 12 hours (6:00 - 18:00) 15 locations Survey [9/21/2009 – 10/2/2009] (3) 6-hour Traffic Count 1 weekday 6 hours (6:00 - 12:00 or 50 locations Survey [9/21/2009 – 10/2/2009] 13:00 – 19:00) Source: JICA Study Team The attached map describes the survey locations. -

UG-IDP-12 A3 07July09 Amuru District IDP Camps & Return Sites

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug AMURU DISTRICT: IDP Camps and Return Sites Population (May 2009) http://ochaonline.un.org Moyo e Uganda Overview Moyo Sudan SUDAN Congo (Dem. Rep) Bibia Kenya Adropi Dzaipi Kitgum Tanzania Rwanda Adjumani ATIAK Population by site Vilages 15904 Transit sites 3907 IDP Camps 11500 Returnees 19811 Oroko Atiak Pakelle Ciforo Palukere Adjumani Ofua Palaro Population by site Pawel Gulu Vilages 19457 Bira Transit sites 10343 Olinga IDP Camps 21604 Returnees 29800 Lugore Patiko- PABBO Otong Ajulu Pabbo Omee Awach Upper Jeng- Gari Population by site Vilages 29783 Cet Kana Lukodi Transit sites 4572 Population by site IDP Camps 13212 Parabongo Vilages 32842 Returnees 34355 AMURU Transit sites 8159 a IDP Camps 10897 LAMOGI Omee Returnees 41001 Coope Lower Mon Roc Awer Olwal Pagak Labongo- Kaladima Ogali Amuru Unyama Keyo Lacor Population by site Alokolum Vilages 15546 Langol Transit sites 12168 Te-tugu IDP Camps 1757 Koro- Returnees 12168 abili ALERO Alero Ongako Amuru Corner Nwoya Koch Palenga Goma Anaka Wii Anaka Bobi Tegot Wii ANAKA Lolim Anono Aparanga Population by site Purongo Olwiyo Vilages 12873 Awoo Transit sites 1449 IDP Camps 9348 Okwir Minakulu Nebbi Agung Returnees 14322 PURONGO KOCH GOMA Population by site Vilages 5819 Transit sites 1487 Population by site IDP Camps 4880 Vilages 18082 Returnees 7306 Transit sites 2046 IDP Camps 2792 Oyam Returnees 20128 Masindi AMURU DISTRICT Total Sub-counties 8 Parishes 51 Villages 114 IDP Camps 33 Return Sites 99 Villages 150,306 Popula Transit sites 44,131 tion in IDP Camps 75,990 Total Returnees 178,891 Data Sources: This map is a work in progress. -

HEALTH and WASH PROGRAMS Projections for 2008 in Northern Uganda

HEALTH AND WASH PROGRAMS Projections for 2008 in Northern Uganda The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has been present in Uganda since 1979 and has a field presence in five northern districts of Gulu, Oyam, Amuru, Kitgum and Pader. Christian Kettiger/ICRC ICRC’s Dr. Willy Mukungi talks to patients waiting for consultations at Kitgum Hospital - November 2007. ICRC Health program for 2008 The ICRC will continue its support to 14 health centres and Committees (HUMC) will be empowered and trained to enhance one hospital in Northern Uganda in 2008. community responsibility in health, an essential aspect of a PHC system as articulated in the Bamako Initiative. Since the North of Uganda has seen positive political devel- opments (thanks to the ongoing peace talks between the The ICRC is involved in 14 health centres II and III, spread across Uganda government and the Lord’s Resistance Army), the the four districts of Acholiland: ICRC’s health programme aims to bridge the gap between emergency response and development funds to govern- a) Pawel, Bibia and Tegot health centres in Amuru district mental institutions. b) Labworomor and Lugore health centres in Gulu district c) Lagot, Dibolyec and Anaka health centres in Kitgum Primary Health Care (PHC) comprehensive approach district d) Omot, Alim, Arum, Awere, Lagile and Porogali in Pader The ICRC’s strategy is to reinforce the efforts of district health district. authorities in their work aimed at redeploying a comprehensive primary health care network in their territories. This strategy in- According to the level of each health centre, the ICRC guaran- cludes capacity building of relevant staff, training and/or super- tees access to safe and clean water and, with the support of the vision, as well as regular medicine refurbishment.