Arxiv:1805.08185V2 [Physics.Atom-Ph] 21 Jan 2021 Δω Δα Δµ = Qα + Qµ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1 Some Astrophysical Reminders

Appendix 1 Some Astrophysical Reminders Marc Ollivier 1.1 A Physics and Astrophysics Overview 1.1.1 Star or Planet? Roughly speaking, we can say that the physics of stars and planets is mainly governed by their mass and thus by two effects: 1. Gravitation that tends to compress the object, thus releasing gravitational energy 2. Nuclear processes that start as the core temperature of the object increases The mass is thus a good parameter for classifying the different astrophysical objects, the adapted mass unit being the solar mass (written Ma). As the mass decreases, three categories of objects can be distinguished: ∼ 1. if M>0.08 Ma ( 80MJ where MJ is the Jupiter mass) the mass is sufficient and, as a consequence, the gravitational contraction in the core of the object is strong enough to start hydrogen fusion reactions. The object is then called a “star” and its radius is proportional to its mass. 2. If 0.013 Ma <M<0.08 Ma (13 MJ <M<80 MJ), the core temperature is not high enough for hydrogen fusion reactions, but does allow deuterium fu- sion reactions. The object is called a “brown dwarf” and its radius is inversely proportional to the cube root of its mass. 3. If M<0.013 Ma (M<13 MJ) the temperature a the center of the object does not permit any nuclear fusion reactions. The object is called a “planet”. In this category one distinguishes giant gaseous and telluric planets. This latter is not massive enough to accrete gas. The mass limit between giant and telluric planets is about 10 terrestrial masses. -

"High Accuracy Rotation--Vibration Calculations on Small Molecules" In

High Accuracy Rotation–Vibration Calculations on Small Molecules Jonathan Tennyson Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, London, UK 1 INTRODUCTION comprehensive understanding requires the knowledge of many millions, perhaps even billions, of individual transi- High-resolution spectroscopy measures the transitions bet- tions (Tennyson et al. 2007). It is not practical to measure ween energy levels with high accuracy; typically, uncer- this much data in the laboratory and therefore a more real- tainties are in the region of 1 part in 108. Although it is istic approach is the development of an accurate theoretical possible, under favorable circumstances, to obtain this sort model, benchmarked against experiment. of accuracy by fitting effective Hamiltonians to observed The incompleteness of most experimental datasets means spectra (see Bauder 2011: Fundamentals of Rotational that calculations are useful for computing other properties Spectroscopy, this handbook), such ultrahigh accuracy is that can be associated with spectra. The partition functions largely beyond the capabilities of purely ab initio proce- and the variety of thermodynamic properties that are linked dures. Given this, it is appropriate to address the question to this (Martin et al. 1991) are notable among these. Again, of why it is useful to calculate the spectra of molecules ab calculations are particularly useful for estimating these initio (Tennyson 1992). quantities at high temperature (e.g., Neale and Tennyson The concept of the potential energy surfaces, which in 1995). turn is based on the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, Other more fundamental reasons for calculating spectra underpins nearly all of gas-phase chemical physics. The include the search for unusual features, such as clustering of original motivation for calculating spectra was to provide energy levels (Jensen 2000) or quantum monodromy (Child stringent tests of potential energy surfaces. -

The Rotational Spectrum of Protonated Sulfur Dioxide, HOSO+

A&A 533, L11 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117753 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor The rotational spectrum of protonated sulfur dioxide, HOSO+ V. Lattanzi1,2, C. A. Gottlieb1,2, P. Thaddeus1,2, S. Thorwirth3, and M. C. McCarthy1,2 1 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Engineering & Applied Sciences, Harvard University, 29 Oxford St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 3 I. Physikalisches Institut, Universität zu Köln, Zülpicher Str. 77, 50937 Köln, Germany Received 21 July 2011 / Accepted 19 August 2011 ABSTRACT Aims. We report on the millimeter-wave rotational spectrum of protonated sulfur dioxide, HOSO+. Methods. Ten rotational transitions between 186 and 347 GHz have been measured to high accuracy in a negative glow discharge. Results. The present measurements improve the accuracy of the previously reported centimeter-wave spectrum by two orders of magnitude, allowing a frequency calculation of the principal transitions to about 4 km s−1 in equivalent radial velocity near 650 GHz, or one linewidth in hot cores and corinos. Conclusions. Owing to the high abundance of sulfur-bearing molecules in many galactic molecular sources, the HOSO+ ion is an excellent candidate for detection, especially in hot cores and corinos in which SO2 and several positive ions are prominent. Key words. ISM: molecules – radio lines: ISM – molecular processes – molecular data – line: identification 1. Introduction abundant in hot regions; (6) and radio observations of SH+ and SO+ (Menten et al. 2011; Turner 1994) have established that pos- Molecules with sulfur account for about 10% of the species iden- itive ions of sulfur-bearing molecules are surprisingly abundant tified in the interstellar gas and circumstellar envelopes. -

Water on the Sun: the Sun Yields More Secrets to Spectroscopy

Contemporary Physics, 1998, volume 39, number 4, pages 283 ± 294 Water on the Sun: the Sun yields more secrets to spectroscopy JONATHAN TENNYSON and OLEG L. POLYANSKY Analysis of sunlight, which started the discipline of spectroscopy, has been the key to a number of major scienti® c discoveries. Sunspots, which are much cooler than most of the Sun’s surface, have particularly rich and complicated spectra which has long been thought to be due to very hot water. The challenge of analysing this spectrum has stimulated the development of new theoretical procedures based on full quantum mechanical treatments of the vibrational and rotational motion of the water molecule. The result has been the identi® cation of novel spectral features and a deeper understanding of how excited molecules such as superheated water behave. This work has applications ranging from the models of cool star atmospheres and rocket exhausts to the possible automated detection of forest ® res. Perhaps the most interesting result is the insight given to understanding how our own atmosphere absorbs sunlight, and the possible consequences that this may have for modelling the greenhouse eŒect. 1. Spectroscopy and the Sun Sun’s photosphere. The remaining absorptions are caused In 1814 Fraunhofer allowed a beam of sunlight from a by molecules such as water and oxygen in the Earth’s narrow opening in his shutters to pass through a prism and atmosphere which also absorb sunlight. Such spectral to be projected onto a white wall. What Fraunhofer saw analysis of light, possible both at visible and non-visible was not only the colours of the rainbow, which had been wavelengths, yields the vast majority of our knowledge not observed in this manner since Newton, but also `almost only about the rest of the Universe but also about the countless strong and weak vertical lines’ [1], see ® gure 1. -

A Diatomic Molecule Is One Atom Too Few the Successful Laser Cooling of a Triatomic Molecule Paves the Way Towards the Study of Ultracold Polyatomic Molecules

VIEWPOINT A Diatomic Molecule is One Atom too Few The successful laser cooling of a triatomic molecule paves the way towards the study of ultracold polyatomic molecules. by Paul Hamilton∗ and Eric R. Hudsony hysicists considering a foray into the study of molecules are often warned that “a diatomic molecule is one atom too many!” [1]. Now John Doyle and colleagues [2] at Harvard University have Pthrown this caution to the wind and tackled laser cooling of a triatomic molecule with success, opening the door to the study of ultracold polyatomic molecules. The technique of laser cooling [3], which uses the scat- tering of laser photons and the concomitant momentum transfer to bring atoms to a near halt, has revolutionized atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physics. Laser cooling and an important variant known as Sisyphus cooling [4] un- derpin three Nobel prizes in physics—for magneto-optical trapping (1997), Bose-Einstein condensation (2001), and the manipulation of individual quantum systems (2012)—and are crucial to a host of quantum-assisted technologies and fundamental physics measurements. Since photons carry very little momentum and therefore reduce an atom’s velocity by just a small amount, a pre- requisite for effective laser cooling is the ability to scatter thousands of photons. Thus laser cooling has predominantly been used only to cool simple atoms, whose electronic struc- ture dictates that after a photon is absorbed, spontaneous Figure 1: Doyle and colleagues [2] have cooled SrOH molecules emission places the atomic electron back into its original using Sisyphus cooling. In this type of cooling, the SrOH state, allowing the process to repeat nearly ad infinitum. -

Rotational Hybridization, and Control of Alignment and Orientation in Triatomic Ultralong-Range Rydberg Molecules

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience Rotational hybridization, and control of alignment and orientation in triatomic ultralong-range Rydberg molecules This content has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text. 2015 New J. Phys. 17 013021 (http://iopscience.iop.org/1367-2630/17/1/013021) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 138.5.159.110 This content was downloaded on 14/03/2015 at 01:03 Please note that terms and conditions apply. New J. Phys. 17 (2015) 013021 doi:10.1088/1367-2630/17/1/013021 PAPER Rotational hybridization, and control of alignment and orientation in OPEN ACCESS triatomic ultralong-range Rydberg molecules RECEIVED 24 June 2014 Rosario González-Férez1,2, H R Sadeghpour3 and Peter Schmelcher2,4 ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION 1 Instituto Carlos I de Física Teórica y Computacional, and Departamento de Física Atómica, Molecular y Nuclear, Universidad de 3 December 2014 Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain PUBLISHED 2 The Hamburg Center for Ultrafast Imaging, Luruper Chaussee 149, D-22761 Hamburg, Germany 15 January 2015 3 ITAMP, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 4 Zentrum für Optische Quantentechnologien, Universität Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, D-22761 Hamburg, Germany Content from this work may be used under the E-mail: [email protected] terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Keywords: Rydberg molecules, electric field, control of alignment and orientation, ultralong-range licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author Abstract (s) and the title of the work, journal citation and We explore the electronic structure and rovibrational properties of an ultralong-range triatomic Ryd- DOI. -

H I in Space

Hiin Space Steven Miller and Jonathan Tennyson* Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, London WCl E 6BT 1 Introduction removal of one of them leaves a pair of electrons in a strong SOMETIMES science is beautiful because something that is bonding orbital. This gives H: an energy of formation, from really complex turns out to have an inner simplicity. When Crick neutral H, and a proton, of 4.8 electron volts, making it 0.3 eV and Watson finally put together their double helix model of DNA, more tightly bound than H,. they just knew they had it; it was just so elegant. Other times, As a result of its simplicity, Hi has attracted a great deal of natural beauty lies in the ability of quite simple systems to carry theoretical and experimental interest. Theoreticians have out, and be responsible for, very complicated processes. The treated it as a test-bed for all sorts of problems from the hydrogen molecular ion Hf3 is like that. In what follows, we hope to calculation of very accurate electronic potential energy surfaces explain to you why, whatever else we might have done and might to studies of chaos and the relation between classical and do, Hi will always have a special place in our scientific affections. quantum mechanics. One of the greatest challenges to our In 1912, J. J. Thomson wrote a paper called ‘Further Experi- understanding of what happens to molecules when they start to ments on Positive Rays’.’ In it he drew attention to a track on the break apart has been posed by a series of beautiful pre- photographic plate he was using to record his hydrogen dis- dissociation spectra obtained by Alan Carrington and his charge experiments which had a mass to charge ratio of three. -

Consequences of Mass-Independent, Chemical, Oxygen-Isotopic Fractionation in the Solar Nebula Joseph A

Lunar and Planetary Science XXIX 1801.pdf Consequences of Mass-Independent, Chemical, Oxygen-Isotopic Fractionation in the Solar Nebula Joseph A. Nuth III, As- trochemistry Branch, Code 691, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 Widespread, systematic, non-mass-dependent, oxygen- evaporates as an atom (e.g. Fe) or a simple diatomic molecule isotopic differences have been documented in analyses of (e.g. SiO), reacts with a large but reasonably dilute reservoir of many different meteorite classes (Thiemens, 1988; Clayton, oxygen (e.g. H2O) to form a triatomic molecule (such as SiO2) Mayeda and Molini-Velsko, 1985) in a variety of studies be- having a much lower vapor pressure than the diatomic species ginning after the initial discovery of this effect (Clayton, (Schick, 1960). This triatomic molecule then condenses on Grossman and Mayeda, 1973). Commonly held explanations any available surface at a rate proportional to its vapor-phase for these differences involve at least three, and sometimes concentration. Less refractory species (e.g. SiO) would re- four very different reservoirs of oxygen isotopes in the primi- main in the vapor until they too form trimers. If the isotopi- tive nebula (Thiemens, 1988). In the simplest model, exchange cally non-symmetric trimer is indeed more easily stabilized due occurs between a 16-0-rich solid reservoir (potentially carried to the larger number of vibrationally active modes available to by grains produced in a supernova), a 16-0-poor solid reser- it, then such a reaction sequence would "extract" 17-O and 18- voir of pre-existing molecular-cloud grains and a larger reser- O from the gas-phase reservoir via preferential reaction of the voir of oxygen-containing gas. -

Chemical and Dynamical Processes in the Atmospheres of I. Ancient and Present-Day Earth II

Chemical and Dynamical Processes in the Atmospheres of I. Ancient and Present-Day Earth II. Jupiter and Galilean Satellites III. Extrasolar \Hot Jupiters" Thesis by Mao-Chang Liang In Partial Ful¯llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 2006 (Defended Nov 7, 2005) ii °c 2006 Mao-Chang Liang All Rights Reserved iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for not stopping me from doing academic research; they completely supported my decision. (In Chinese culture, children's plans are mostly under their parents' control.) I would also like to acknowledge my master's thesis advisor, Professor Fred Lo, for teaching me how to be a good scientist and re- searcher. The major thing I learned from him is that, to be a good scientist, one has to remember that theory and experiments are equally important. For working on theory, one has to think of what experiments can support your theory; for experimentalists, to interpret the results requires a deep understanding of the background physics or theory. This clearly is seen from my Ph.D. advisors, Professors Yuk Yung and Ge- o® Blake, who work closely with theorists and experimentalists. Their great help in launching my research career has been invaluable. I would then want to thank my girlfriend, Bows Chiou, and colleagues Mark Allen, Mimi Gerstell, Xun Jiang, Anthony Lee, Chris Parkinson, Run-Lie Shia, and many others for their insightful comments/discussion on my research. Financial support from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Science Foundation (NSF) are ac- knowledged. -

Here Is an Ambitious and Vigorous Space Program Leading to Eventual Space Settlement

Welcome to the 15th Australian Space Research Conference and to the University of New South Wales, Canberra! This will be the ninth ASSC jointly sponsored and organised by the National Committee for Space and Radio Science (NCSRS) and the National Space Society of Australia (NSSA). The ASRC is intended to be the primary annual meeting for Australian research relating to space science. It welcomes space scientists, engineers, educators, and workers in Industry and Government. The 15th ASRC has over 120 accepted abstracts across Australian space research, academia, education, industry, and government. We would like to thank the University of New South Wales (Canberra) for hosting the event, led by Russell Boyce, and Lockheed Martin for their sponsorship. Special thanks also go to the Australian Space Mars Society Australia (MSA) for its support. We look forward to an excellent meeting! Iver Cairns Wayne Short Co-Chair ASSC 2015 Co-Chair ASSC 2015 University of Sydney President, NSSA 1 Contents About the NSSA ........................................................... 3 About the NCSRS .......................................................... 4 Program Committee & Organisers ................................... 5 Program Overview ........................................................ 7 Venue Details ............................................................... 8 Detailed Program ........................................................ 11 Invited Speakers ........................................................ 24 Oral Presentations ..................................................... -

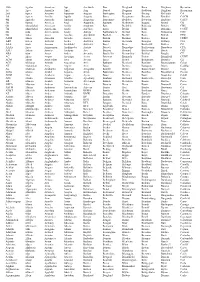

10Th 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th 7Th 8Th 9Th A&M A&P AAA

10th Agatha Amadeus Apr Auerbach Barr Berglund Boca Brigham Byzantine 1st Agee Amarillo April Aug Barrett Bergman Bodleian Brighton Byzantium 2nd Agnes Amazon Aquarius Augean Barrington Bergson Boeing Brillouin CA 3rd Agnew Amelia Aquila Augusta Barry Bergstrom Boeotia Brindisi CACM 4th Agricola Amerada Aquinas Augustan Barrymore Berkeley Boeotian Brisbane CATV 5th Agway America Arab Augustine Barstow Berkowitz Bogota Bristol CB 6th Ahmadabad American Arabia Augustus Bart Berkshire Bohemia Britain CBS 7th Ahmedabad Americana Arabic Aurelius Barth Berlin Bohr Britannic CCNY 8th Aida Americanism Araby Auriga Bartholomew Berlioz Bois Britannica CDC 9th Aides Ames Arachne Auschwitz Bartlett Berlitz Boise British CEQ A&M Aiken Ameslan Arcadia Austin Bartok Berman Bolivia Briton CERN A&P Aileen Amherst Archer Australia Barton Bermuda Bologna Brittany CIA AAA Ainu Amman Archibald Australis Basel Bern Bolshevik Britten CO AAAS Aires Ammerman Archimedes Austria Bassett Bernadine Bolshevism Broadway CPA AAU Aitken Amoco Arcturus Ave Batavia Bernard Bolshevist Brock CRT ABA Ajax Amos Arden Aventine Batchelder Bernardino Bolshoi Broglie CT AC Akers Ampex Arequipa Avery Bateman Bernardo Bolton Bromfield CUNY ACM Akron Amsterdam Ares Avesta Bates Bernet Boltzmann Bromley CZ ACS Alabama Amtrak Argentina Avis Bathurst Bernhard Bombay Brontosaurus Cabot AK Alabamian Amy Argive Aviv Bator Bernice Bonaparte Bronx Cadillac AL Alameda Anabaptist Argonaut Avogadro Battelle Bernie Bonaventure Brooke Cady AMA Alamo Anabel Argonne Avon Baudelaire Berniece Boniface -

Chapter-15: BIODIVERSITY and CONSERVATION

Downloaded from www.studiestoday.com Chapter-15: BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION IMPORTANT SCIENTISTS AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION SL.NO SCIENTIST CONTRIBUTION 1 EDWARD WILSON POPULARISED THE TRM BIODIVERSITY 2 ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT BROUGHTOUT SPECIES AREA RELATIONSHIP 3 DAVID TILMAN BROUGHTOUT CHARACTERESTICS OF ASTABLLE BIOLOGICAL COMMUNITY THROUGH LONG TERM EXPERIMENTS. 4 PAUL EHRLICH RIVET POPPER HYPOTHESIS Biodiversity is defined as the totality of genes, species and ecosystems of a given region, It is the variety and variability of life form (all animals, plants and microbes on earth) and the ecological complexes in which they occur. The term was popularized by the American sociobiologist Edward Wilson(1988) Hierarchial levels of Biodiversirty: 1)Species Diversity 2)Genetic Diversity and. 3)Ecosystem/Community/Habitat Diversity Refer Fig no.15.1,Pie chart representing global Biodiversity Patterns of Biodiversity: Downloaded from www.studiestoday.com 1) Latitudinal gradients – species diversity decreases, from equator to poles. Tropics (23.50N -23.50S) show richest species diversity. Speciation is generally a function of time. Temperate region is subjected to glaciations. Tropical regions remained relatively undisturbed for millions of years and thus had a long evolutionary time for species diversification. Tropical environments are less seasonal, relatively more constant and predictable. Constant environment facilitates niche specialisation and lead to greater species diversity. Tropical latitudes also get huge solar radiations which promote higher productivity. SPECIES – Area relationships : This is reflected in the quantitative formula S = cAz, in which S represents the species richness and A the size of the area. The constant c represents y intercept ,.z is regression coefficient. ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT observed within a region species richness increased with increasing explored area but only up to a limit.