The Hunt for GTAV's Bigfoot And/As Digital Cultural Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Lan Ps4 Digital Manual E

PHOTOSENSITIVITY/EPILEPSY/SEIZURES A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your doctor before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your doctor before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: • dizziness, • eye or muscle twitches, • disorientation, • any involuntary • altered vision, • loss of awareness, • seizures, or movement or convulsion. RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR DOCTOR. Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. • Avoid prolonged use of the PlayStation®4 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. 3D images Some people may experience discomfort (such as eye strain, eye fatigue, or nausea) while watching 3D video images or playing stereoscopic 3D games on 3D televisions. If you experience such discomfort you should immediately discontinue use of your television until the discomfort subsides. SIE recommends that all viewers take regular breaks while watching 3D video, or playing stereoscopic 3D games. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

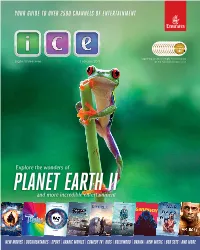

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages. -

Cinema and Tourism

© 2018 JETIR May 2018, Volume 5, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Cinema and Tourism Dr. Gunjan Malik Assistant Professor IHTM, MDU Abstract: Films play an eloquent role in customers’ decision making regarding choice of clothes, fashion, food and also the destination they want to travel. It has been proved by previous studies that when films are shot in a destination it boosts tourism. Government also offers various initiatives to promote film shooting so that tourism can be encashed. In this paper with the help of secondary data the status of film tourism has been identified in India as well as international destinations. The study found that films give a boost to tourism and various international destinations have been trying to woo Indian film makers to shoot at their locations. Even the ministry of tourism, government of India also gives incentives to filmmakers in order to promote film tourism. Keywords: film tourism, cinema, tourism, movies. Introduction Bollywood is a cardinal part of Indian society and has a considerable impact on the members of society. Cinema is one of the significant communication tools for conveying social values, social evils, corruption, sexual exploitation, historical events, drama or even tourism. Anything or everything can be communicated effectively to the society with the help of films or cinema. India, Brazil and China are the emerging travel and tourism markets and they are expected to supersede even the developed markets because of the development in infrastructure and increase in the disposable incomes. Placing or showcasing destinations in movies which helps in increasing tourism of that particular place is known as film tourism. -

Films 2018.Xlsx

List of feature films certified in 2018 Certified Type Of Film Certificate No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Production House Type ngth l/Celluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH 1 LITTLE GANDHI VFL/1/68/2018-MUM 13 June 2018 91.38 Video HOUSE OF FILM - U ENGLISH SUBTITLE Assamese SVF 1 AMAZON ADVENTURE Assamese DIL/2/5/2018-KOL 02 January 2018 140 Digital Ravi Sharma ENTERTAINMENT UA PVT. LTD. TRILOKINATH India Stories Media XHOIXOBOTE 2 Assamese DIL/2/20/2018-MUM 18 January 2018 93.04 Digital CHANDRABHAN & Entertainment Pvt UA DHEMALITE. MALHOTRA Ltd AM TELEVISION 3 LILAR PORA LEILALOI Assamese DIL/2/1/2018-GUW 30 January 2018 97.09 Digital Sanjive Narain UA PVT LTD. A.R. 4 NIJANOR GAAN Assamese DIL/1/1/2018-GUW 12 March 2018 155.1 Digital Haider Alam Azad U INTERNATIONAL Ravindra Singh ANHAD STUDIO 5 RAKTABEEZ Assamese DIL/2/3/2018-GUW 08 May 2018 127.23 Digital UA Rajawat PVT.LTD. ASSAMESE WITH Gopendra Mohan SHIVAM 6 KAANEEN DIL/1/3/2018-GUW 09 May 2018 135 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das CREATION Ankita Das 7 TANDAB OF PANDAB Assamese DIL/1/4/2018-GUW 15 May 2018 150.41 Digital Arian Entertainment U Choudhury 8 KRODH Assamese DIL/3/1/2018-GUW 25 May 2018 100.36 Digital Manoj Baishya - A Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 9 HAPPY MOTHER'S DAY Assamese DIL/1/5/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 108.08 Digital U Chavan Society, India Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 10 GILLI GILLI ATTA Assamese DIL/1/6/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 85.17 Digital U Chavan Society, India SEEMA- THE UNTOLD ASSAMESE WITH AM TELEVISION 11 DIL/1/17/2018-GUW 25 June 2018 94.1 Digital Sanjive Narain U STORY ENGLISH SUBTITLES PVT LTD. -

GTA IV Setup and Crack Full Free Download GTA IV Rar Zip.Rar

GTA IV Setup And Crack Full Free Download GTA IV Rar Zip.rar GTA IV Setup And Crack Full Free Download GTA IV Rar Zip.rar 1 / 3 2 / 3 run LaunchGTAIV.exe instead GTAIV.exe (to prevent "drunk" camera) ... Der Download wurde von uns mit Hilfe bekannter Programme überprüft, jedoch ist eine 100%ige ... Ive been up all night trying to figure out how to get these mods to work. ... All I did was copy the xlive.dll into installation directory.. Download gta 5 Highly Compressed 20mb Free Download PC Game setup in single direct link for windows. When a ... Gta 4 full complete zip file. Gta 4 full .... Double click on "Setup.exe" and Install the game. Play the game. ... GTA IV 3. GTA IV V1.0.0.0 Crack Full Free Download GTA IV Rar Zip.rar .... 7 GB setup Size [ crack ] without DLC 13 GB setup Size [ Crack ] with DLC Zip and Rar files size may Vary 14GB Original version & 25GB DLC included .... GTA IV Setup And Crack Full Free Download GTA IV Rar Zip.125 http://urllio.com/sgobj a4c8ef0b3e Download Packs for GTA San Andreas for .... The 1.0.3.0 patch for Grand Theft Auto IV. ... Download Patch 1.0.3.0. More Grand Theft Auto IV Mods. The 1.0.3.0 ... GTAIV_Patch_1030.rar, 3,377, 24 Mar 2009 .... Grand Theft Auto V : 27 GB DOWNLOAD. ... Processor: Intel Core 2 Duo 1.8Ghz, AMD Athlon X2 64 2.4Ghz. ... All Files At Pc RepaX are Splitted Into Multiple Parts to Serve Bandwidth Friendly Downloads. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

March 15, 2021

MARCH 15, 2021 MARCH 15, 2021 Tab le o f Contents 4 #1 Songs THIS week 5 powers 6 action / recurrents 8 hotzone / developiong 10 pro-file 12 video streaming 13 Top 40 callout 14 Hot ac callout 15 future tracks 16 spotlight 17 intelevision 18 methodology 19 the back page Songs this week #1 BY MMI COMPOSITE CATEGORIES 3.15.21 ai r p lay OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” retenTion THE WEEKND “Save Your Tears” callout 24kgoldn “Mood” (ft. Iann Dior) audio LIL TJAY “Calling My Phone” (ft. 6lack) VIDEO CARDI B “Up” SALES OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” COMPOSITE OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” mmi-powers 3.15.21 Weighted Airplay, Retention Scores, Streaming Scores, and Sales Scores this week combined and equally weighted deviser Powers Rankers. TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW COMP AIRPLAY RETENTION CALLOUT AUDIO VIDEO SALES RANK ARTIST TITLE LABEL 1 12 2 3 3 3 1 OLIVIA RODRIGO drivers license Geffen/Interscope 8 2 1 8 14 12 2 24KGOLDN Mood f/Iann Dior RECORDS/Columbia 9 1 19 4 8 5 3 THE WEEKND Save Your Tears XO/Republic 2 7 7 7 9 30 4 ARIANA GRANDE 34+35 Republic 28 x 25 2 1 2 5 CARDI B Up Atlantic 6 3 3 17 19 23 6 CHRIS BROWN X YOUNG THUG Go Crazy Chris Brown/300 Ent.-RCA 7 8 11 22 17 8 7 TATE MCRAE You Broke Me First RCA 3 9 8 21 25 11 8 BILLIE EILISH Therefore I Am Darkroom/Interscope 4 4 4 18 18 39 9 ARIANA GRANDE positions Republic 10 14 10 19 22 14 10 MACHINE GUN KELLY & BLACKBEAR My Ex’s Best Friend Bad Boy/Interscope 45 x 17 1 2 17 11 LIL TJAY Calling My Phone f/6LACK Columbia 11 19 5 13 20 26 12 POP SMOKE What You Know Bout Love Victor Victor/Republic 13 11 22 23 29 7 13 JUSTIN BIEBER Anyone Def Jam 23 24 13 12 12 6 14 SAWEETIE Best Friend f/Doja Cat Icy/Artistry/RCA-Warner 29 x 27 14 24 4 15 MASKED WOLF Astronaut In The Ocean Elektra/EMG 18 23 9 15 21 15 16 THE KID LAROI Without You Columbia 16 5 16 27 39 18 17 TAYLOR SWIFT willow Republic 5 10 6 37 31 34 18 RITT MOMNEY Put Your Records On Disruptor/Columbia 37 x 24 10 7 31 19 CJ Whoopty Warner 34 16 15 26 13 19 20 MEGAN THEE STALLION Body 1501 Certified/300 Ent. -

LIST of HINDI CINEMA AS on 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days

LIST OF HINDI CINEMA AS ON 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days/ Directed by- Partho Ghosh Class No : 100 HFC Accn No. : FC003137 Location : gsl 2 Title : 15 Park Avenue Class No : FIF HFC Accn No. : FC001288 Location : gsl 3 Title : 1947 Earth Class No : EAR HFC Accn No. : FC001859 Location : gsl 4 Title : 27 Down Class No : TWD HFC Accn No. : FC003381 Location : gsl 5 Title : 3 Bachelors Class No : THR(3) HFC Accn No. : FC003337 Location : gsl 6 Title : 3 Idiots Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC001999 Location : gsl 7 Title : 36 China Town Mn.Entr. : Mustan, Abbas Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001100 Location : gsl 8 Title : 36 Chowringhee Lane Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001264 Location : gsl 9 Title : 3G ( three G):a killer connection Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC003469 Location : gsl 10 Title : 7 khoon maaf/ Vishal Bharadwaj Film Class No : SAA HFC Accn No. : FC002198 Location : gsl 11 Title : 8 x 10 Tasveer / a film by Nagesh Kukunoor: Eight into ten tasveer Class No : EIG HFC Accn No. : FC002638 Location : gsl 12 Title : Aadmi aur Insaan / .R. Chopra film Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002409 Location : gsl 13 Title : Aadmi / Dir. A. Bhimsingh Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002640 Location : gsl 14 Title : Aag Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC001678 Location : gsl 15 Title : Aag Mn.Entr. : Raj Kapoor Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC000105 Location : MSR 16 Title : Aaj aur kal / Dir. by Vasant Jogalekar Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. : FC002641 Location : gsl 17 Title : Aaja Nachle Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. -

Intellectual Resonance DCAC Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies

ISSN: 2321-2594 Intellectual DCAC Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies December - 2013 Vol.-I Issue-II Intellectual Resonance DCAC Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 1 Issue No. II ISSN: 2321-2594 Published and Printed by: DELHI COLLEGE OF ARTS AND COMMERCE (UNIVERSITY OF DELHI) NETAJI NAGAR, NEW DELHI-110023 Phone : 011-24109821,26116333 Fax : 26882923 e-mail : [email protected] website-http://www.dcac.du.in © Intellectual Resonance The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors Printed at: Xpress Advertising, C-114, Naraina Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi-28 Editorial Advisory Board, Intellectual Resonance (IR) 1) Prof. Daing Nasir Ibrahim 2) Prof. Jancy James Vice-Chancellor Vice-Chancellor University of Malaysia Central University of Kerala [email protected] [email protected] 3) Prof.B.K. Kuthiala 4) Dr. Daya Thussu Vice-Chancellor Professor, Department of Journalism Makhanlal Charturvedi Rashtriya and Mass Communication Patrakarita Vishwavidyalaya University of Westminster Bhopal United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 5) Prof. Dorothy Figueira 6) Prof. Anne Feldhaus Professor, University of Georgia Professor, Department of Religious Honorary President, International Studies Comparative Literature Association. Arizona State University [email protected] [email protected] 7) Prof. Subrata Mukherjee 8) Prof. Partha S. Ghosh Professor, Department of Political Senior Fellow Science Nehru Memorial Museum and Library University Of Delhi (NMML) [email protected] [email protected] 9) Prof. B.P. Sahu 10) Dr. Anil Rai Professor, Department Of History Professor Hindi Chair University Of Delhi Peking University, Beijing, PR of China. [email protected] [email protected] 11) Dr.