Rereading Haunted House Films from a Gothic Perspective ᐙᗞෆ࠶ࡿ༴ᶵ ࢦࢩࢵࢡ◊✲ࡽ ㄞࡳ┤ࡍᗃ㟋ᒇᩜᫎ⏬㸧

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

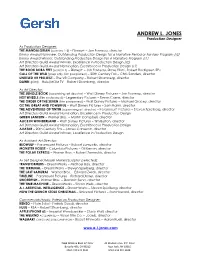

JONES-A.-RES-1.Pdf

ANDREW L. JONES Production Designer As Production Designer: THE MANDALORIAN (seasons 1-3) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, director Emmy Award Nominee, Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program (s2) Emmy Award Winner, Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Program (s1) Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design (s2) Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design (s1) THE BOOK BOBA FETT (season 1) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Robert Rodriguez, EPs CALL OF THE WILD (prep only, film postponed) – 20th Century Fox – Chris Sanders, director UNTITLED VR PROJECT – The VR Company – Robert Stromberg, director DAWN (pilot) – Hulu/MGM TV – Robert Stromberg, director As Art Director: THE JUNGLE BOOK (supervising art director) – Walt Disney Pictures – Jon Favreau, director HOT WHEELS (film postponed) – Legendary Pictures – Simon Crane, director THE ORDER OF THE SEVEN (film postponed) – Walt Disney Pictures – Michael Gracey, director OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL – Walt Disney Pictures – Sam Raimi, director THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (supervising art director) – Paramount Pictures – Steven Spielberg, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design GREEN LANTERN – Warner Bros. – Martin Campbell, director ALICE IN WONDERLAND – Walt Disney Pictures – Tim Burton, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design AVATAR – 20th Century Fox – James Cameron, director Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design As Assistant Art Director: BEOWULF – Paramount Pictures – Robert Zemeckis, director MONSTER HOUSE – Columbia Pictures – Gil Kenan, director THE POLAR EXPRESS – Warner Bros. – Robert Zemeckis, director As Set Designer/Model Maker/Sculptor (selected): TRANSFORMERS – DreamWorks – Michael Bay, director THE TERMINAL – DreamWorks – Steven Spielberg, director THE LAST SAMURAI – Warner Bros. -

A Complete History of the Film and Television Adaptations from The

Illustrated with a fabulous array of familiar and unusual iconography, this is a complete account of the films and television series adapted from the work of Stephen King — the literary Steven Spielberg. Including fresh A Complete History of the Film and Television Adaptations critical analysis, interviews, making of stories and biographical elements, from the Master of Horror it is a King completist’s dream and a set text for any movie fan. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY PUBLICATION Autumn 2020 Ian Nathan, who lives and works in London, is one of ILLUSTRATIONS 200 full-colour the UK’s best-known writers on fi lm. He is the best-selling PRICE £25 author of nine books, including Alien Vault, the best-selling EXTENT 240pp history of Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, biographies on FORMAT 275 x 215mm Tim Burton, The Coen Brothers and Quentin Tarantino, and BINDING Hardback Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of TERRITORIES UK Commonwealth Middle-earth. He is the former editor and executive editor of Empire, still the world’s biggest movie magazine, where he remains a contributing editor. He was also creative For further information, please contact: director of the Empire Awards for fi fteen years, as well as Palazzo Editions Limited producing television documentaries, events, and launching 15 Church Road Empire Online. He also regularly contributes to The Times, London SW13 9HE The Independent, The Mail on Sunday, Cahiers Du Cinema, Tel +44 (0)208 878 8747 Talk Radio and the Discovering Film documentary series Email [email protected] on Sky Arts. www.palazzoeditions.com STEPHENKING_BLAD_COVER.indd 1 19/03/2018 18:04 What do you consider is the best fi lm adaptation of your work? ‘Probably Stand by Me. -

Ghost Hunting

Haunted house in Toledo Ghost Hunting GHOST HUNTING 101 GHOST HUNTING 102 This course is designed to give you a deeper insight into the This course is an extended version of Ghost Hunting 101. While world of paranormal investigation. Essential characteristics of it is advised that Ghost hunting 101 be taken as a prerequisite, it a paranormal investigation require is not necessary. This class will expand on topics of paranormal a cautious approach backed up investigations covered in the first class. It will also cover a variety with scientific methodology. Learn of topics of interest to more experienced investigators, as well as, best practices for ghost hunting, exploring actual techniques for using equipment in ghost hunting, investigating, reviewing evidence and types of hauntings, case scenarios, identifying the more obscure presenting evidence to your client. Learn spirits and how to deal with them along with advanced self- from veteran paranormal investigator protection. Learn from veteran paranormal investigator, Harold Harold St. John, founder of Toledo Ohio St. John, founder of the Toledo Ohio Ghost Hunters Society. If you Ghost Hunters Society. We will study have taken Ghost Hunting 101 and have had an investigation, you the different types of haunting's, a might want to bring your documented evidence such as pictures, typical case study of a "Haunting", the EVP’s or video to share with your classmates. There will be three Harold St. John essential investigating equipment, the classes of lecture and discussions with the last session being a investigation process and how to deal field trip to hone the skills you have learned. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Texas Paranormalists

! TEXAS PARANORMALISTS David!Goodman,!B.F.A,!M.A.! ! ! Thesis!Prepared!for!the!Degree!of! MASTER!OF!FINE!ARTS! ! ! UNIVERSITY!OF!NORTH!TEXAS! December!2015! ! APPROVED:!! Tania!Khalaf,!Major!Professor!!!!! ! Eugene!Martin,!Committee!Member!&!!!! ! Chair!for!the!Department!of!Media!Arts ! Marina!Levina,!Committee!Member!!!! ! Goodman, David. “Texas Paranormalists.” Master of Fine Arts (Documentary Production and Studies), December 2015, 52 pp., references, 12 titles. Texas Pararnormalists mixes participatory and observational styles in an effort to portray a small community of paranormal practitioners who live and work in and around North Texas. These practitioners include psychics, ghost investigators, and other enthusiasts and seekers of the spirit world. Through the documentation of their combined perspectives, Texas Paranormalists renders a portrait of a community of outsiders with a shared belief system and an unshakeable passion for reaching out into the unknown. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright!2015! By! David!Goodman! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ii! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Page! PROSPECTUS………………………………………………………………………………………………………!1! Introduction!and!Description……………………………………………………………………..1! ! Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………….………3! ! Intended!Audience…………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! Preproduction!Research…….....................…………………………………………...…………..6! ! ! Feasibility……...……………...…………….………………………………………………6! ! ! Research!Summary…….…...…..……….………………………………………………7! Books………...………………………………………………………………………………..8! -

History of Commercial Filming at White Sands

White Sands National Park Service Department of the Interior White Sands National Monument History of Commercial Filming at White Sands owering mountains, spectacular white dunes, crystal blue skies, stunning Tsunsets, and magical moonlit nights—all of these unique features form the amazing landscape at White Sands National Monument. Half a million visitors from all over the world enjoy this beautiful place every year. Commercials, feature films, fashion catalogs, music videos, made-for-TV movies, and documentaries also come to White Sands to capture this scenery and beauty on film. History of Filming Since the early days of film on the Clydesdales, Energizer Bunny, and silver screen, national parks have Marlboro Man. Well known directors been popular destinations for Steven Spielberg (Transformers) and photographers, videographers, and Harold Ramus (Year One), actors cinematographers. The rolling bright Denzel Washington (Book of Eli) white sand dunes have set the scene and Willem Defoe (White Sands: The for westerns, science fiction films, Movie), and music performers Boyz and apocalyptic films. They have II Men (“Water Runs Dry”) and Sara also provided the backdrop to still Evans (“I Could Not Ask for More”) photography of dawn breaking or sun have all spent time at White Sands setting and for commercials featuring capturing the dunes in their Rolls Royce, the Anheuser-Busch creative work. Motion Pictures Movie Production Date Production House King Solomon’s Mines 1950 MGM Hang ‘Em High 1968 United Artists Scandalous John 1970 Disney My Name is Nobody 1973 Titanus Bite the Bullet 1974 Columbia The Man Who Fell to Earth 1975 EMI Convoy 1977 United Artists Raw Courage 1983 RB Productions Wrong Is Right 1981 Columbia Young Guns II 1990 Morgan Creek Lucky Luke 1991 Paloma Films White Sands 1991 Morgan Creek New Eden 1993 HBO Tank Girl 1994 MGM Mad Love 1994 Disney Astronaut Farmer 2005 Warner Independent Transformers 2006 Dreamworks, LLC Afterwards 2007 Et Apres, Inc. -

Between Static and Slime in Poltergeist

Page 3 The Fall of the House of Meaning: Between Static and Slime in Poltergeist Murray Leeder A good portion of the writing on Poltergeist (1982) has been devoted to trying to untangle the issues of its authorship. Though the film bears a directorial credit from Tobe Hooper, there has been a persistent claim that Steven Spielberg (credited as writer and producer) informally dismissed Hooper early in the process and directed the film himself. Dennis Giles says plainly, “Tobe Hooper is the director of record, but Poltergeist is clearly controlled by Steven Spielberg,” (1) though his only evidence is the motif of white light. The most concerted analysis of the film’s authorship has been by Warren Buckland, who does a staggeringly precise formal analysis of the film against two other Spielberg films and two other Hooper films, ultimately concluding that the official story bears out: Hooper directed the film, and Spielberg took over in postproduction. (2) Andrew M. Gordon, however, argues that Poltergeist deserves a place within Spielberg’s canon because so many of his trademarks are present, and because Spielberg himself has talked about it as a complementary piece for E .T.: The ExtraTerrestrial (1982). (3) A similar argument can be made on behalf of Hooper, however, with respect to certain narrative devices and even visual motifs like the perverse clown from The Funhouse (1981). Other scholars have envisioned the film as more of a contested space, caught between different authorial impulses. Tony Williams, for examples, speaks of Spielberg “oppressing any of the differences Tobe Hooper intended,” (4) which is pure speculation, though perhaps one could be forgiven to expect a different view of family life from the director of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) than that of E.T. -

An October Film List for Cooler Evenings and Candlelit Rooms

AUTUMN An October Film List For cooler evenings and candlelit rooms. For tricks and treats and witches with brooms. For magic and mischief and fall feelings too. And good ghosts and bad ghosts who scare with a “boo!” For dark haunted houses and shadows about. And things unexplained that might make you shout. For autumn bliss with colorful trees or creepier classics... you’ll want to watch these. FESTIVE HALLOWEEN ANIMATED FAVORITES GOOD AUTUMN FEELS BEETLEJUICE CORALINE AUTUMN IN NEW YORK CASPER CORPSE BRIDE BAREFOOT IN THE PARK CLUE FANTASTIC MR. FOX BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S DARK SHADOWS FRANKENWEENIE DEAD POET’S SOCIETY DOUBLE DOUBLE TOIL AND TROUBLE HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA MOVIES GOOD WILL HUNTING E.T. JAMES AND THE GIANT PEACH ONE FINE DAY EDWARD SCISSORHANDS MONSTER HOUSE PRACTICAL MAGIC GHOSTBUSTERS PARANORMAN THE CRAFT HALLOWEENTOWN THE GREAT PUMPKIN CHARLIE BROWN THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK HOCUS POCUS THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS WHEN HARRY MET SALLY LABYRINTH YOU’VE GOT MAIL SLEEPY HOLLOW THE ADAMS FAMILY MOVIES THE HAUNTED MANSION THE WITCHES SCARY MOVIES A HAUNTING IN CONNECTICUT RELIC THE LODGE A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET ROSEMARY’S BABY THE MOTHMAN PROPHECIES AMMITYVILLE HORROR THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE THE NUN ANNABELLE MOVIES THE BABADOOK THE OTHERS AS ABOVE SO BELOW THE BIRDS THE POSSESSION CARRIE THE BLACKCOAT’S DAUGHTER THE POSSESSION OF HANNAH GRACE HALLOWEEN MOVIES THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT THE SHINING HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL THE CONJURING MOVIES THE SIXTH SENSE INSIDIOUS MOVIES THE EXORCISM OF EMILY ROSE THE VILLAGE IT THE EXORCIST THE VISIT LIGHTS OUT THE GRUDGE THE WITCH MAMA THE HAUNTING THE WOMAN IN BLACK POLTERGEIST THE LAST EXORCISM It’s alljust a bit of hocus pocus.. -

ED VERREAUX Production Designer Verreauxfilmdesign.Com

ED VERREAUX Production Designer verreauxfilmdesign.com FEATURE FILMS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS SKYSCRAPER Consultant Rawson Marshall Thurber Beau Flynn, Wendy Jacobson / Legendary MONSTER HIGH Consultant Ari Sandel Jeff La Plante, Lisbeth Rowinski Mattel Inc. / Universal MEGAN LEAVEY Gabriela Cowperthwaite Bob Huberman, Mickey Liddell LD Entertainment JURASSIC WORLD Colin Trevorrow Patrick Crowley, Frank Marshall Nominated, Best Fantasy Feature Film – ADG Awards Universal Pictures THE GIVER Phillip Noyce Ralph Winter / The Weinstein Company WARM BODIES Add’l Photography Jonathan Levine Ogden Gavanski / Summit Entertainment LOOPER Rian Johnson Ram Bergman, Dave Pomier, James Stern Endgame Entertainment SEASON OF THE WITCH Add’l Photography Dominic Sena Tom Karnowski, Alan Glazer / Lionsgate G.I. JOE: THE RISE OF COBRA Stephen Sommers Lorenzo di Bonaventura, Bob Ducsay David Womark / Paramount RUSH HOUR 3 Brett Ratner Roger Birnbaum, Andy Davis Jonathan Glickman / New Line MONSTER HOUSE Gil Kenan Steven Spielberg, Steve Starkey Sony/Columbia X-MEN: THE LAST STAND Brett Ratner Avi Arad, Lauren Shuler Donner th Ralph Winter / 20 Century Fox STARSKY & HUTCH Todd Phillips Stuart Cornfeld, Akiva Goldsman Alan Riche / Warner Bros. THE SCORPION KING Chuck Russell Stephen Sommers, Kevin Misher James Jacks / Universal Pictures JURASSIC PARK III Joe Johnston David Womark, Kathleen Kennedy Steven Spielberg / Universal Pictures MISSION TO MARS Brian De Palma Tom Jacobson, Sam Mercer Spyglass Entertainment / Disney CONTACT Robert Zemeckis Steve Starkey -

Conference Schedule

Gothic: Culture, subculture, counterculture Conference Programme (Please see from p.7 onwards for abstracts and participants’ contact details) Key to rooms: AR= Anteroom RR= Round Room WDR = Waldegrave Drawing Room SCR = Senior Combination Room BR = Billiard Room/D121 Day 1: Friday, 8 March 9.00 Coffee, Danish Pastries and Introductions (AR) 9.30-10.45: Parallel Session 1 Panel 1A (WDR): Gothic and Genre Fiction: Ghosts and Crime (Chair: Brian Ridgers) Marta Nowicka, ‘Gothic Ghosts from Horace Walpole to Muriel Spark’ Victoria Margree, ‘(Other) Wordly Goods: Gothic Inheritances in the Ghost Stories of Charlotte Riddell’ Andalee Motrenec, ‘Gothic Elements and Crime Fiction in Dracula and Frankenstein’ Panel 1B (BR): Southern European Gothic Architecture Graça P. Corrêa, ‘Gothic Spatial Theory and Aesthetics: The Ecocentric Conjoining of Underworld and Otherworld in Regaleira (Sintra, Portugal)’ Viviane Delpech, ‘The château d’Abbadia in Hendaye (France) : Antoine d’Abbadie’s romantic and political utopia’ Giulio Girondi, ‘Gothic Heritage in Renaissance Mantova’ Panel 1C (SCR): Gothic in Contemporary Fiction (Chair: Fred Botting) Andrew Teverson, ‘Blood Relations: Salman Rushdie and Anish Kapoor’s Gothic Nights’ Nadia van der Westhuizen, ‘Happily Ever Aftermath: Fairy Tales in Contemporary Gothic Fiction and Television’ Martin Dines, ‘American Suburban Gothic’ Panel 1D (RR): Horace Walpole and the Cultures of the Eighteenth Century (Chair: Fiona Robertson) Hsin Hsuan (Cynthia) Lin, ‘The Castle of Otranto and Strawberry Hill House: the Curious Cases’ Jonanthan Dent, ‘History’s Other: Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto and David Hume’s The History of England’ Zara Naghizadeh, ‘Horace Walpole’s ”Guardianship of Embryos and Cockleshells”’ Gothic: Culture, Subculture, CounterCulture An interdisciplinary Conference, 8-9 March 2013 www.smuc.ac.uk/gothic – Twitter: @StrawHillGothic – FB Group: ‘Gothic: Culture, Subculture, Counterculture’ 10.45 Refreshments (AR) 11.00 Plenary 1 (WDR): Avril Horner, ‘Walpole, the Gothic, and Surrealism’. -

The Amityville Horror, by Jay Anson. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1977

The Amityville Horror, by Jay Anson. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1977. 201 pages, $7.95. Reviewed by Robert L. Morris This book claims to be the true account of a month of terrifying "paranormal" events that occurred to a Long Island family when they moved into a house in Amityville, New York, that had been the scene of a mass murder. Throughout the book there are strong suggestions that the events were demonic in origin. On the copyright page, the Library of Congress subject listings are "1. Demon- ology—Case studies. 2. Psychical research—United States—Case studies." The next page contains the following statement: "The names of several individuals mentioned in this book have been changed to protect their privacy. However, all facts and events, as far as we have been able to verify them, are strictly accurate." The front cover of the book's dust jacket contains the words: "A True Story." A close reading, plus a knowledge of details that later emerged, suggests that this book would be more appropriately indexed under "Fiction—Fantasy and horror." In fact it is almost a textbook illustration of bad investigative jour- nalism, made especially onerous by its potential to terrify and mislead people and to serve as a form of religious propaganda. To explore this in detail, we first need an outline of the events that supposed- ly took place, as described in the text of the book, plus a prologue derived from a segment of a New York television show about the case. On November 13, 1974, Ronald DeFeo shot to death six members of his family at their home in Amityville. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A.