The Philippines Stocktaking Report on Sustainable Transport and Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participating Petron Service Stations September 6

LIST OF PARTICIPATING PETRON SERVICE STATIONS SEPTEMBER 6 - 21, 2021 REGION CITY / MUNICIPALITY ADDRESS METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 245 SUSANO ROAD, DEPARO KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY ZABARTE ROAD, BRGY. CAMARIN, NORTH CALOOCAN, KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 146RIZAL AVENUE EXT. GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 510 A. MABINI ST., KALOOKAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY C-3 ROAD, DAGAT-DAGATAN CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY BLK 46 CONGRESSIONAL ROAD EXT., BAG CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY B. SERRANO ST. COR 11TH AVE CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY GEN. SAN MIGUEL ST., SANGANDAAN, CALOOCAN CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD LAS PINAS, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 2A DAANG HARI CORNER DAANG REYN LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS NAGA ROAD LAS PINAS CITY, METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS BLK 14 LOT 1 VERSAILLES SUBD DAANG LAS PIбAS CITY METRO MANILA LAS PINAS CRM AVENUE, BF ALMANZA, LAS PIбAS METRO MANILA METRO MANILA LAS PINAS LOT 1 & 2 J. AGUILAR AVENUE TALON TRES, LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS ALABANG ZAPOTE RD., PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 269 REAL ST. PAMPLONA LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 109 MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON LAS PINAS METRO MANILA LAS PINAS 469 REAL ST., ZAPOTE LAS PINAS METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 46 GIL PUYAT AVE. NEAR COR. DIAN MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY G PUYAT COR P TAMO AVE, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY LOT 18 BLOCK 76 SEN. GIL PUYAT AVE. PALANAN, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY PETRON DASMARINAS STATION EDSA, MAKATI CITY METRO MANILA MAKATI CITY 363 SEN. -

Current Bus Service Operating Characteristics Along EDSA, Metro Manila

TSSP 22 nd Annual Conference of the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines Iloilo City, Philippines, 12 Sept 2014 2014 Current Bus Service Operating Characteristics Along EDSA, Metro Manila Krister Ian Daniel Z. ROQUEL Alexis M. FILLONE, Ph.D. Research Specialist Associate Professor Civil Engineering Department Civil Engineering Department De La Salle University - Manila De La Salle University - Manila 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA) has been the focal point of many transportation studies over the past decade, aiming towards the improvement of traffic conditions across Metro Manila. Countless researches have tested, suggested and reviewed proposed improvements on the traffic condition. This paper focuses on investigating the overall effects of the operational and administrative changes in the study area over the past couple of years, from the full system operation of the Mass Rail Transit (MRT) in the year 2000 to the present (2014), to the service operating characteristics of buses plying the EDSA route. It was found that there are no significant changes in the average travel and running speeds for buses running Southbound, while there is a noticeable improvement for those going Northbound. As for passenger-kilometers carried, only minor changes were found. The journey time composition percentages did not show significant changes over the two time frames as well. For the factors contributing to passenger-related time, the presence of air-conditioning and the direction of travel were found to contribute as well, aside from the number of embarking and/or disembarking passengers and number of standing passengers. -

Chapter 5 Project Scope of Work

CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK 5.1 MINIMUM EXPRESSWAY CONFIGURATION 5.1.1 Project Component of the Project The project is implemented under the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Scheme in accordance with the Philippine BOT Law (R.A. 7718) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. The project is composed of the following components; Component 1: Maintenance of Phase I facility for the period from the signing of Toll Concession Agreements (TCA) to Issuance of Toll Operation Certificate (TOC) Component 2: Design, Finance with Government Financial Support (GFS), Build and Transfer of Phase II facility and Necessary Repair/Improvement of Phase I facility. Component 3: Operation and Maintenance of Phase I and Phase II facilities. 5.1.2 Minimum Expressway Configuration of Phase II 1) Expressway Alignment Phase II starts at the end point of Phase I (Coordinate: North = 1605866.31486, East 502268.99378), runs over Sales Avenue, Andrews Avenue, Domestic Road, NAIA (MIA) Road and ends at Roxas Boulevard/Manila-Cavite Coastal Expressway (see Figure 5.1.2-1). 2) Ramp Layout Five (5) new on-ramps and five 5) new off-ramps and one (1) existing off-ramp are provided as shown in Figure 5.1.2-1. One (1) on-ramp constructed under Phase I is removed. One (1) overloaded truck/Emergency Exit is provided. One (1) on-ramp for NAIA Terminal III exit traffic and one existing off-ramp from Skyway for access to NAIA Terminal III. One (1) on-ramp along Andrews Ave. to collect traffic jam from NAIA Terminal III traffic and traffic on Andrews Ave. -

Transportation History of the Philippines

Transportation history of the Philippines This article describes the various forms of transportation in the Philippines. Despite the physical barriers that can hamper overall transport development in the country, the Philippines has found ways to create and integrate an extensive transportation system that connects the over 7,000 islands that surround the archipelago, and it has shown that through the Filipinos' ingenuity and creativity, they have created several transport forms that are unique to the country. Contents • 1 Land transportation o 1.1 Road System 1.1.1 Main highways 1.1.2 Expressways o 1.2 Mass Transit 1.2.1 Bus Companies 1.2.2 Within Metro Manila 1.2.3 Provincial 1.2.4 Jeepney 1.2.5 Railways 1.2.6 Other Forms of Mass Transit • 2 Water transportation o 2.1 Ports and harbors o 2.2 River ferries o 2.3 Shipping companies • 3 Air transportation o 3.1 International gateways o 3.2 Local airlines • 4 History o 4.1 1940s 4.1.1 Vehicles 4.1.2 Railways 4.1.3 Roads • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 External links Land transportation Road System The Philippines has 199,950 kilometers (124,249 miles) of roads, of which 39,590 kilometers (24,601 miles) are paved. As of 2004, the total length of the non-toll road network was reported to be 202,860 km, with the following breakdown according to type: • National roads - 15% • Provincial roads - 13% • City and municipal roads - 12% • Barangay (barrio) roads - 60% Road classification is based primarily on administrative responsibilities (with the exception of barangays), i.e., which level of government built and funded the roads. -

Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using Pagerank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2

“Transportation for A Better Life: Harnessing Finance for Safety and Equity in AEC August 21, 2015, Bangkok, Thailand Hub Identification of the Metro Manila Road Network Using PageRank Paper Identification Number: AYRF15-015 Jacob CHAN1, Kardi TEKNOMO2 1Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, School of Science and Engineering Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines 1108 Telephone +632-426-6001, Fax. +632-4261214 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We attempt to identify the different node hubs of a road network using PageRank for preparation for possible random terrorist attacks. The robustness of a road network against such attack is crucial to be studied because it may cripple its connectivity by simply shutting down these hubs. We show the important hubs in a road network based on network structure and propose a model for robustness analysis. By identifying important hubs in a road network, possible preparation schemes may be done earlier to mitigate random terrorist attacks, including defense reinforcement and transportation security. A case study of the Metro Manila road network is also presented. The case study shows that the most important hubs in the Metro Manila road network are near airports, piers, major highways and expressways. Keywords: PageRank, Terrorist Attack, Robustness 1. Introduction Table 1 Comparative analysis of different Roads are important access points because methodologies on network robustness indices connects different places like cities, districts, and Author Method Strength Weakness landmarks. -

2019 Financial Statements

Cavitex Infrastructure Corp. Financial Statements December 31, 2019 and 2018 and Independent Auditor’s Report SyCip Gorres Velayo & Co. Tel: (632) 891 0307 BOA/PRC Reg. No. 0001, 6760 Ayala Avenue Fax: (632) 819 0872 October 4, 2018, valid until August 24, 2021 1226 Makati City ey.com/ph SEC Accreditation No. 0012-FR-5 (Group A), Philippines November 6, 2018, valid until November 5, 2021 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT The Stockholders and the Board of Directors Cavitex Infrastructure Corp. Report on the Audit of the Financial Statements Opinion We have audited the financial statements of Cavitex Infrastructure Corp. (the Company), which comprise the statements of financial position as at December 31, 2019 and 2018, and the statements of comprehensive income, statements of changes in equity and statements of cash flows for the years then ended, and notes to the financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies. In our opinion, the accompanying financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the Company as at December 31, 2019 and 2018, and its financial performance and its cash flows for the years then ended in accordance with Philippine Financial Reporting Standards (PFRSs). Basis for Opinion We conducted our audits in accordance with Philippine Standards on Auditing (PSAs). Our responsibilities under those standards are further described in the Auditor’s Responsibilities for the Audit of the Financial Statements section of our report. We are independent of the Company in accordance with the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants in the Philippines (Code of Ethics) together with the ethical requirements that are relevant to our audit of the financial statements in the Philippines, and we have fulfilled our other ethical responsibilities in accordance with these requirements and the Code of Ethics. -

Results Report 2014

Results Report 2014 Results Report 2014 26th February, 2015 Non Audited Figures 1 Results Report 2014 INDEX 1 Executive Summary 3 1.1 Main figures 3 1.2 Relevant facts 5 2 Consolidated Financial Statements 8 2.1 Income Statement 8 2.1.1 Sales and Backlog 8 2.1.2 Operating Results 10 2.1.3 Financial Results 11 2.1.4 Net Profit Attributable to the Parent Company 12 2.2 Consolidated Balance Sheet 13 2.2.1 Non-Current Assets 13 2.2.2 Assets held for sale 14 2.2.3 Working Capital 15 2.2.4 Net Debt 15 2.2.5 Net Worth 16 2.3 Net Cash Flows 17 2.3.1 Operating Activities 17 2.3.2 Investments 18 2.3.3 Other Cash Flows 18 3 Areas of Activity Evolution 19 3.1 Construction 19 3.2 Industrial Services 22 3.3 Environment 24 4 Relevant facts after the end of the period 26 5 Description of the main risks and opportunities 26 6 Corporate Social Responsibility 28 6.1 Ethics 28 6.2 Efficiency 28 6.3 Employees 30 7 Information on affiliates 30 8 Annexes 31 8.1 Main figures per area of activity 31 8.2 Financial Accounts per area of Activity 32 8.2.1 Income Statement 32 8.2.2 Balance Sheet 33 8.3 Infrastructure Concessions 34 8.4 Share data 35 8.5 Exchange rate effect 36 8.6 Main Awards of the Period 37 8.6.1 Construction 37 8.6.2 Industrial Services 40 8.6.3 Environment 41 Non Audited Figures 2 Results Report 2014 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Main figures Grupo ACS Key operating & financial figures Million Euro 2013 2014 Var. -

OTH: Philippines

Increase in Budget of CDTA Strengthening Public-Private Partnerships in the Philippines (PHI 45515) PERFORMANCE OVERVIEW 1. TA implementation has progressed much better that expected. With its focus on improving PPP governance framework, the TA has become the anchor of the Government’s PPP program. This role of the TA was further re-enforced through PPP becoming a major component of the program cluster Increasing Competiveness for Inclusive Growth. The progress of implementation of the TA’s capacity building and Project Development and Monitoring Facility (PDMF) components is summarized below. 2. Capacity building component is progressing well. a. GHD Pty Ltd (Australia), the international firm on PPP policy, institutional, legal, information management strengthening and capacity building has (i) advanced in developing a comprehensive manual on PPPs for national government agencies (NGAs), (ii) substantially updated the PPP manual for local government units (LGUs) developed with support of the World Bank, (iii) submitted the first draft review of the government’s institutional set-up for PPPs, and (iv) submitted first two policy papers on selected PPP topics to inform the process of amending the BOT Law.1 The two manuals, which will cover the whole PPP project cycle, will be adopted by the Infrastructure Committee of the NEDA Board by end June 2012. GHD’s training of PPP Center staff, government oversight agencies, and selected line-departments on priority PPP topics will be completed by June 2012. b. Twelve national2 and two international consultants3 have been provided to the PPP Center. These have been critically supporting the PPP Center in coping with the increased demand for its services and contributed an enhanced quality of PPP Center’s performance. -

Business Directory Commercial Name Business Address Contact No

Republic of the Philippines Muntinlupa City Business Permit and Licensing Office BUSINESS DIRECTORY COMMERCIAL NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTACT NO. 12-SFI COMMODITIES INC. 5/F RICHVILLE CORP TOWER MBP ALABANG 8214862 158 BOUTIQUE (DESIGNER`S G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG BOULEVARD) 158 DESIGNER`S BLVD G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER AYALA ALABANG 890-8034/0. EXTENSION 1902 SOFTWARE 15/F ASIAN STAR BUILDING ASEAN DRIVE CORNER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION SINGAPURA LANE FCC ALABANG 3ARKITEKTURA INC KM 21 U-3A CAPRI CONDO WSR CUPANG 851-6275 7 MARCELS CLOTHING INC.- LEVEL 2 2040.1 & 2040.2 FESTIVAL SUPERMALL 8285250 VANS FESTIVAL ALABANG 7-ELEVEN RIZAL ST CORNER NATIONAL ROAD POBLACION 724441/091658 36764 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE EAST SERVICE ROAD ALABANG SERVICE ROAD (BESIDE STORE PETRON) 7-ELEVEN CONVENIENCE G/F REPUBLICA BLDG. MONTILLANO ST. ALABANG 705-5243 STORE MUNT. 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE UNIT 1 SOUTH STATION ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD 5530280 7-ELEVEN FOODSTORE 452 CIVIC PRIME COND. FCC ALABANG 7-ELEVEN/FOODSTORE MOLINA ST COR SOUTH SUPERH-WAY ALABANG 7MARCELS CLOTHING, INC. UNIT 2017-2018 G/F ALABANG TOWN CENTER 8128861 MUNTINLUPA CITY 88 SOUTH POINTER INC. UNIT 2,3,4 YELLOW BLDG. SOUTH STATION FILINVEST 724-6096 (PADIS POINT) ALABANG A & C IMPORT EXPORT E RODRIGUEZ AVE TUNASAN 8171586/84227 66/0927- 7240300 A/X ARMANI EXCHANGE G/F CORTE DE LAS PALMAS ALAB TOWN CENTER 8261015/09124 AYALA ALABANG 350227 AAI WORLDWIDE LOGISTICS KM.20 WEST SERV.RD. COR. VILLONGCO ST CUPANG 772-9400/822- INC 5241 AAPI REALTY CORPORATION KM22 EAST SERV RD SSHW CUPANG 8507490/85073 36 AB MAURI PHILIPPINES INC. -

Malolos-Clark Railway Project – Tranche 1 Volume I

Environmental Monitoring Report Semi-annual Environmental Monitoring Report No. 1 March 2020 PHI: Malolos-Clark Railway Project – Tranche 1 Volume I September 2019 – March 2020 Prepared by the Project Management Office (PMO) of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for the Government of the Republic of the Philippines and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 March 2020) Currency unit – Philippine Peso (PHP) PHP1.00 = $0.02 $1.00 = PHP50.96 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BMB – Biodiversity Management Bureau Brgy – Barangay CCA – Climate Change Adaptation CCC – Climate Change Commission CDC – Clark Development Corporation CEMP – Contractor’s Environmental Management Plan CENRO – City/Community Environment and Natural Resources Office CIA – Clark International Airport CIAC – Clark International Airport Corporation CLLEx – Central Luzon Link Expressway CLUP – Comprehensive Land Use Plan CMR – Compliance Monitoring Report CMVR – Compliance Monitoring and Validation Report CNO – Certificate of No Objection CPDO – City Planning and Development Office DAO – DENR Administrative Order DD / DED – Detailed Design Stage / Detailed Engineering Design Stage DENR – Department of Environment and Natural Resources DepEd – Department of Education DIA – Direct Impact Area DILG – Department of Interior and Local Government DOH – Department of Health DOST – Department of Science and Technology DOTr – Department of Transportation DPWH – Department of Public Works and Highways DSWD – Department of Social Welfare and Development -

No. Area Municipality Address

NO. AREA MUNICIPALITY ADDRESS 1 MNM BULACAN KM 23 NLEX, MARILAO BULACAN 2 MNM BULACAN NORTH LUZON TOLLWAYS, SOUTHBOUND BOCAUE, BULACAN 3 MNM BULACAN BGY MALAMIG BUSTOS, BULACAN 4 MNM BULACAN 48 NORTHERN HILLS, MALHACAN, MEYCAUAYAN, BULACAN 5 MNM BULACAN KM 42 NLEX, NORTHBOUND LANE, PLARID BULACAN 6 MNM BULACAN MAHARLIKA HIGHWAY, GALA-MAASIM, SAN BULACAN 7 MNM BULACAN PUROK 1 MABINI STREET, SANTISSIMA T MALOLOS, BULACAN 8 MNM BULACAN KM 37 BGY CUTCUT, BULIHAN PLARIDEL, BULACAN 9 MNM BULACAN MAHARLIKA HIGHWAY BRGY. SAMPALOC SAN RAFAEL, BULACAN 10 MNM BULACAN VILLARAMA ST., POBLACION NORZAGARAY, BULACAN 11 MNM BULACAN BRGY. TAAL DRT HIGHWAY PULILAN BULACAN 12 MNM BULACAN GROTTO, SAN JOSE DEL MONTE BULACAN 13 MNM BULACAN 595 McARTHUR HIGHWAY, BO. TUKTUKAN GUIGUINTO, BULACAN 14 MNM BULACAN BO. TURO, BOCAUE BULACAN 15 MNM BULACAN DIVERSION ROAD (BY PASS), STA. CLAR STA. MARIA, BULACAN 16 MNM BULACAN DULONG BAYAN, STA. MARIA BULACAN 17 MNM BULACAN 101 MCARTHUR HIGHWAY BULACAN 18 NCR CALOOCAN C-3 ROAD, DAGAT-DAGATAN CALOOCAN CITY 19 NCR CALOOCAN B. SERRANO ST. COR 11TH AVE CALOOCAN CITY 20 NCR CALOOCAN GEN. LUIS CORNER P. DELA CRUZ STS. KALOOKAN CITY 21 NCR CALOOCAN ZABARTE ROAD, BRGY. CAMARIN, NORTH CALOOCAN, KALOOKAN CITY 22 NCR CALOOCAN TULLAHAN ROAD, ST. QUITERIA CALOOCAN CITY 23 NCR CALOOCAN 486 EDSA CORNER A DE JESUS ST., CALOOCAN 24 NCR LAS PINAS LOT 2A DAANG HARI CORNER DAANG REYN LAS PINAS 25 NCR LAS PINAS C5 EXT. COR. S. MARQUEZ ST. MANUYO TALON, LAS PINAS 26 NCR LAS PINAS 269 REAL ST. PAMPLONA LAS PINAS 27 NCR LAS PINAS C5 EXT. -

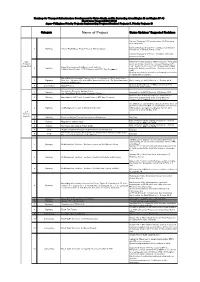

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016).