Improving Management of Government-Owned Real Property in Tennessee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lee, Blackburn Claim TN Victory

6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 69, Number 19 Nov. 12, 2018 Lee, Blackburn claim TN victory TML District Meetings Thursday, Nov. 29 District 4 Crossville Friday, Nov. 30 District 3 Collegedale Tuesday, Dec. 4 District 5 Gallatin Wednesday, Dec. 5 District 2 Morristown Thursday, Dec. 6 District 1 Greeneville Monday, Dec. 10 District 7 Henderson Tuesday, Dec. 11 District 8 Millington Friday, Dec 14 District 6 Columbia Mark your calendars and plan to attend! Photos by The Tennessean Tennesseans elected Repub- And I couldn’t be more grateful,” Corker, who after serving two lican Bill Lee as the state’s 50th Lee said during his acceptance terms opted not to run again. governor on Nov. 6, voting into speech. “I’m grateful you placed Blackburn won the seat with office a political newcomer. Lee your trust in us to lead this great 55 percent of the votes to Bre- easily defeated former Nashville state of Tennessee.” desen’s 44 percent. Mayor Karl Dean with 60 percent Lee will be sworn into office Blackburn has served the of the votes to Dean’s 39 percent. on Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019, in 7th Congressional District in the Lee, 59, is a Tennessean busi- Nashville. House of Representatives since nessman and CEO of his family’s Republican Marsha Blackburn 2003. She previously served in the HVAC, plumbing, and electrical defeated former Tennessee Gov- Tennessee Senate from 1999 to business, Lee Company. He cam- ernor Phil Bredesen to become 2003. paigned on a socially and fiscally Tennessee’s first female elected to For a complete results of conservative platform. -

General Election State of Tennessee Tennessee House of Representatives District 1

State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 1 1 . Jon C. Lundberg - (R) 1 SULLIVAN 17,503 DISTRICT TOTALS 17,503 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 2 1 . Tony Shipley - (R) 2 . Bruce Dotson - (D) 1 2 SULLIVAN 16,764 7,794 DISTRICT TOTALS 16,764 7,794 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 3 1 . Timothy Hill - (R) 2 . Leah R. Kirk - (D) 3 . Suzanne Parker - (G) 1 2 3 CARTER 2,747 521 148 JOHNSON 4,300 1,018 238 SULLIVAN 8,963 2,880 449 DISTRICT TOTALS 16,010 4,419 835 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 4 1 . Thomas Gray - (R) 2 . Kent Williams - (I) 1 2 CARTER 6,334 9,112 UNICOI 3,553 2,361 DISTRICT TOTALS 9,887 11,473 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 5 1 . David B. Hawk - (R) 2 . Eddie Yokley - (D) 3 . Write-In - Jason Scott Moore 1 2 3 GREENE 11,566 8,292 1 DISTRICT TOTALS 11,566 8,292 1 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 6 1 . James (Micah) Van Huss - (R) 2 . Michael Clark - (D) 1 2 WASHINGTON 16,391 6,271 DISTRICT TOTALS 16,391 6,271 05-Dec-12 State of Tennessee November 6, 2012 General Election Tennessee House of Representatives District 7 1 . -

Building Tennessee's Tomorrow: Anticipating the State's

Report of the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations Building Tennessee’s Tomorrow: Anticipating the State’s Infrastructure Needs July 2019 through June 2024 Rabia Chaudhry, M.P.A., M.S. Project Manager David L. Keiser, M.A. Senior Research Associate Project Manager Tyler Carpenter, M.P.A. Senior Research Associate Mark McAdoo, D.B.A. Research Manager Other Contributing Staff Mark S. Patterson, B.A. Information Systems Manager Teresa Gibson Web Development & Publications Manager January 2021 TACIR staff wish to acknowledge the efforts of the development district staff responsible for the inventory: East Tennessee Development District South Central Tennessee Development District Terry Bobrowski, Executive Director Jerry Mansfield, Executive Director Mollie Childress, Infrastructure Planner Lisa Cross, RPO/Infrastructure Director Kayla Baxter, Agricultural and Environmental First Tennessee Development District Resource Coordinator Chris Craig, Executive Director Misty Bradley, Program Assistant Southeast Tennessee Development District Ken Rea, Deputy Director, Economic and Beth Jones, Executive Director Community Development Chuck Hammonds, Assistant Executive Director Bill Forrester, Director of Industrial Development Sam Saieed, Asst. Director of Community & Housing Development Gray Stothart, Community Development Chad Reese, Planning Director Coordinator/Historic Preservation Planner Ashley Yingling Gates, Regional Planner Garrett Haynes, Regional Planner Lance Lowery, Community Development Project Coordinator -

Weather Has the Bill Has Matter

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 227 JANUARY 21, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ A year of project completions ‘State of the City’ eyes present, future By JOYANNA LOVE spur even more economic growth a step closer toward the Spring Banner Senior Staff Writer FIRST OF 2 PARTS along the APD 40 corridor,” Rowland Branch Industrial Park becoming a said. reality. Celebrating the completion of some today. The City Council recently thanked “A conceptual master plan was long-term projects for the city was a He said the successes of the past state Rep. Kevin Brooks for his work revealed last summer, prepared by highlight of Cleveland Mayor Tom year were a result of hard work by city promoting the need for the project on TVA and the Bradley/Cleveland Rowland’s State of the City address. staff and the Cleveland City Council. the state level by asking that the Industrial Development Board,” “Our city achieved several long- The mayor said, “Exit 20 is one of Legislature name the interchange for Rowland said. term goals the past year, making 2015 our most visible missions accom- him. The interchange being constructed an exciting time,” Rowland said. “But plished in 2015. Our thanks go to the “The wider turn spaces will benefit to give access to the new industrial just as exciting, Cleveland is setting Tennessee Department of trucks serving our existing park has been named for Rowland. new goals and continues to move for- Transportation and its contractors for Cleveland/Bradley County Industrial “I was proud and humbled when I ward, looking to the future for growth a dramatic overhaul of this important Park and the future Spring Branch learned this year the new access was and development.” interchange. -

Legislative Bill Turns up Heat on Broadband by BRIAN GRAVES League, State Rep

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 239 FEBRUARY 4, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 18 PAGES • 50¢ Legislative bill turns up heat on broadband By BRIAN GRAVES league, state Rep. Dan Howell, and sev- State Sen. Janice Bowling (R- This is about the people of Tennessee this is still the No. 1 issue from my Banner Staff Writer eral other legislators, business leaders Tullahoma) is the Senate’s sponsor. having access to the 21st century,” constituents.” and regular citizens calling for the pas- State Sen. Todd Gardenhire is a co- Bowling said. “It’s 2016. We need it He said the same technology should State Rep. Kevin Brooks said last sage of House Bill 1303 and Senate Bill sponsor. now.” be available to rural residents as is week there would be a “major 1134. The announcement was the delivery Howell said he had been dealing with available to large cities. announcement” Wednesday concerning The bills would allow utilities who of what Brooks said was “thousands the issue for seven years, beginning Howell said he recently met with broadband access. have the capability of providing broad- and thousands” of signatures by with his time as assistant to the Gov. Bill Haslam, telling the governor It came in the form of a press confer- band Internet to offer it in the service Tennesseans on petitions demanding Bradley County mayor. there are “literally thousands in my ence held in a crowded old Supreme area of another utility, should that the bills be passed. “It was then and is now the No. -

TN State Senators and Representatives Contact List 2021

Senators District Name Phone Email Twi4er Facebook 29 Sen. Raumesh Akbari 615.741.1767 [email protected] @SenAkbari h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenAkbari 15 Sen. Paul Bailey 615.741.3978 [email protected] @PaulBaileyforTN h4ps://www.facebook.com/paulbaileyforsenate 9 Sen. Mike Bell 615.741.1946 [email protected] @SenMikeBell h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenMikeBell 16 Sen. Janice Bowling 615.741.6694 [email protected] @Janicebowlingtn h4ps://www.facebook.com/Senator-Janice-Bowling-202797446470765 7 Sen. Richard Briggs 615.741.1766 [email protected] @SenatorBriggs h4ps://www.facebook.com/RichardBriggsTN 20 Sen. Heidi Campbell 615.741.6679 [email protected] @campbellyn20 h4ps://www.facebook.com/campbelltn20 3 Sen. Rusty Crowe 615.741.2468 [email protected] 10 Sen. Todd Gardenhire 615.741.6682 [email protected] @SenGardenhire h4ps://www.facebook.com/VoteGardenhire 19 Sen. Brenda Gilmore 615.741.2453 [email protected] @SenatorGilmore h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenatorGilmore 18 Sen. Ferrell Haile 615.741.1999 [email protected] @HaileforSenate h4ps://www.facebook.com/FerrellHaileTN 28 Sen. Joey Hensley 615.741.3100 [email protected] @joey_senator h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenatorJoeyHensley 27 Sen. Ed Jackson 615.741.1810 [email protected] @SenEdJackson h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenEdJackson 23 Sen. Jack Johnson 615.741.2495 [email protected] @SenJohnson h4ps://www.facebook.com/SenatorJackJohnson 31 Sen. Brian Kelsey 615.741.3036 [email protected] @BrianKelsey h4ps://www.facebook.com/briankelsey 30 Sen. -

Welcome: As Speaker of the House of Representatives for the 110Th

Beth Harwell Speaker State Capitol Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0104 (615)741-0709 Nashville Office of the Speaker Welcome: As Speaker of the House of Representatives for the 110 th General Assembly, and on behalf of the House members, I want to welcome you to the Tennessee State Capitol. Even with its majestic architecture and rich history, the Capitol building still serves the viable function for which it was erected. On the House floor, Tennessee Representatives work together to handle today’s most challenging issues on behalf of the citizens of Tennessee. Please remember that all Sessions of the General Assembly held in the Chamber, as well as all Committee meetings held in the Cordell Hull Building, are open to the public. I encourage you to take part in the legislative process first hand by attending a Session of the House of Representatives. If you cannot visit us in person, please keep in mind that all sessions of the Tennessee House of Representatives can be viewed from the Legislature’s website. Live and archived videos of all House floor and committee meetings can be found at www.capitol.tn.gov . Please feel free to contact the representative from your home district as you visit the Capitol and the Cordell Hull Building. All of Tennessee’s 99 representatives serve to address any concerns or questions that you may have. Again, I want to thank you for visiting the Tennessee House of Representatives. Sincerely, Beth Harwell Speaker of the House TENNESSEE House of Representatives 110 th General Assembly Beth Harwell , Speaker of the House Curtis Johnson , Speaker Pro Tempore Steve K. -

November 12, 2020 to All Tennesseans, the Tennessee

November 12, 2020 To all Tennesseans, The Tennessee House Republican Caucus unequivocally and staunchly stands with President of the United States Donald J. Trump in demanding that all legal ballots, and only legal ballots, be counted in the 2020 presidential election. Voting is one of the most fundamental pieces of our American republic. One person equals one vote in a system that grants justice and equality for all in deciding our government. In an election where there are alleged examples of voter fraud and malpractice, Tennessee Republicans stand with the rule of law. We shall not accept the idea that the national media or the political elite have the official say on the winner of any election, let alone the presidency. It is up to the official systems put in place by the constitution and by the people. When there are alleged software glitches, lost or destroyed ballots, and questionable practices implemented in some areas of the country, litigation must have a day in court to decide the outcome of this election process. We uphold the idea of protecting the rights of all Americans, liberal or conservative, to have their voices heard. After all legal ballots are counted and any illegal ballots are removed, we support confirming the victor. A peaceful transition to the next term, whether it be the incumbent or the challenger, is paramount to our system of government. We stand with all Tennesseans in defending the integrity of elections. We are asking for the election process to have the ability to finish before prematurely declaring a winner. -

Agency Distribution List for Presentation 8-13-19

Invasive Aquatic Species RCERB/WBEFC Workshop August 15, 2019 List of Agencies & Legislative Bodies Contacts Contacts TVA Board of Directors email: [email protected] St Rep William Frank Fiss, Tennessee Wildlife Resource Lamberth email: [email protected] Agency email: [email protected] St Rep Martin Daniel email: [email protected] Lamar Alexander email: [email protected] St Rep Dwayne Scott DesJarlais email: [email protected] Thompson email: [email protected] John J. Duncan Jr. email: [email protected] St Rep Craig Fitzhugh email: [email protected] Charles J. Fleischmann email: [email protected] St Rep Gerald David P. Roe email: [email protected] McCormick email: [email protected] David Kustoff email: [email protected] St Rep Johnnie Turner email: [email protected] Diane Black email: [email protected] St Rep Mary Littleton email: [email protected] Steve Cohen email: [email protected] St Rep David Byrd email: [email protected] Jim Cooper email: [email protected] St Rep Mark Lovell email: [email protected] Senator Bob Corker email: [email protected] St Rep John Forgety email: [email protected] Marsha Blackburn for Senate St Rep Steve McDaniel email: [email protected] email: [email protected] St Rep Terri Lynn Phil Bredesen for Senate email: [email protected] Weaver email: [email protected] Add Governor Bill Lee St Rep Harold M. -

State of Tennessee 2017-2018

53380 110th House Comp - v3.1.qxp 12/6/18 8:30 AM Page 1 TheHouse of Representatives David Alexander Bill Beck Clark Boyd Harry Brooks Kevin Brooks Sheila Butt David Byrd Kent Calfee Karen Camper Dale Carr Moore, Franklin, Marion Davidson Cannon, Wilson, DeKalb Knox Bradley Maury Hardin, Lewis, Wayne, Roane, Loudon Shelby Sevier 2018 Lawrence Mike Carter John Ray Clemmons Jim Coley Barbara Cooper John Crawford Michael Curcio Martin Daniel John DeBerry, Jr. Barry Doss Bill Dunn Jimmy Eldridge Jeremy Faison Hamilton Davidson Shelby Shelby Sullivan Hickman, Maury, Dickson Knox Shelby Giles, Lawrence Knox Madison Cocke, Greene, Jefferson Bill Haslam Beth Harwell GOVERNOR SPEAKER Davidson 110th General Assembly Andrew Farmer John Forgety Ron Gant Brenda Gilmore Tilman Goins Marc Gravitt Curtis Halford G.A. Hardaway Patsy Hazlewood Gary Hicks Matthew Hill John Holsclaw, Jr. Jefferson, Sevier McMinn, Monroe Fayette, McNairy, Hardeman Davidson Hamblen Hamilton State of Tennessee Gibson, Carroll Shelby Hamilton Hancock, Hawkins Washington Unicoi, Carter 2017-2018 Andy Holt Dan Howell Bud Hulsey Darren Jernigan Sherry Jones Roger Kane Kelly Keisling Sabi Kumar William Lamberth Mary Littleton Weakley, Obion, Carroll Meigs, Polk, Bradley Sullivan Davidson Davidson Knox Macon, Clay, Pickett Robertson Sumner Cheatham, Dickson Scott, Fentress Curtis Johnson Glen Casada Ryan Williams David Hawk MicahVan Huss Timothy Hill Steve McDaniel SPEAKER PRO TEMPORE MAJORITY LEADER MAJORITY ASSISTANT MAJORITY FLOOR LEADER MAJORITY WHIP DEPUTY SPEAKER Montgomery Williamson CAUCUS CHAIRMAN LEADER Washington Johnson, Carter, Sullivan Henderson, Chester, Putnam Greene Decatur, Perry Ron Lollar Harold Love, Jr. Mark Lovell Susan Lynn Pat Marsh Judd Matheny Jimmy Matlock Gerald McCormick Larry Miller Bo Mitchell Shelby Davidson Shelby Wilson Bedford, Lincoln Coffee, Warren Loudon, Monroe Hamilton Shelby Davidson 2017 Craig Fitzhugh Mike Stewart Joe Towns, Jr. -

Nov 23, 2020.Indd

6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 71, Number 18 Nov. 23, 2020 Bill Hagerty wins U.S. Senate seat Registration now open! Virtual TML District Meetings set for December The 112th General Assembly Tennessee Municipal Bond Fund will convene in Nashville on Jan. President and CEO Wade Morrell, 12. TML anticipates they will ad- and a brief message from our new dress a number of issues that will TML Executive Director Anthony impact cities and towns in our state. Haynes. It is important that all city officials Information on how to register are prepared to voice support or for each meeting has already been concern with their legislators and sent to city officials in each district. help educate them on the needs of A meeting reminder and Zoom our cities and towns. link will be sent out prior to each This year’s TML District meeting. For further assistance, Meetings will be conducted virtu- please contact your TML staff. ally using a Zoom webinar format. Accordingly, this district meeting 2020 TML Virtual will be conducted on an abbreviated District Meetings schedule and the information will be related in a condensed format. The District 1 Dec. 2 10a.m./ EST abbreviated meeting is expected to District 2 Dec. 3 10 a.m. / EST Photo by The Tennessean last 75 minutes. District 3 Dec. 9 10 a.m. / EST Republican Bill Hagerty has won the U.S. Senate seat in Tennessee being vacated by retiring, long- TML staff will share the District 4 Dec. 2 1 p.m./ CST legislative agenda created by Ten- time Sen. -

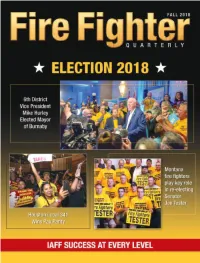

2018-Fall.Pdf

Exclusive stretch PBI®/KEVLAR® GORE® moisture barriers manage heat stress New thermal barrier is lighter, outer shell from TenCate better in a broader range of environments more flexible, and quicker drying NOTHING COMPARES TO ATHLETIX™ Unique stretch fabrics enable all-new athletic turnout gear. Lighter weight, less bulky fit, and all over stretch let you perform like a tactical athlete. Designed to meet the new challenges you face every day to help keep you safe and healthy throughout your career and beyond. globeturnoutgear.com ATHLETIC GEAR FOR FIREFIGHTERS.TM GLOBE, ATHLETIX, and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of Globe Holding Company, LLC. PBI and designs are registered trademarks of PBI Performance Products, Inc. GORE, CROSSTECH, and designs are trademarks of W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc. DUPONT, KEVLAR, NOMEX, and designs are trademarks or registered trademarks of E.I. DuPont de Nemours and Company or its affiliates. Fall 2018 Fire Fighter Quarterly vol. 101 no.4 31 32 Mike Carter sworn in as 6th District Vice President 36 University City members fight back International Burn Camp Cover Features Departments 12 Political Action Helps 22 Disaster Relief On the Frontlines n 5 From the General President Win Elections IAFF provides disaster relief operations for Results in the 2018 elections members following hurricanes in the East n 7 From the General favored the IAFF and affiliates and wildfires in the West. Secretary-Treasurer up and down the ballot. n Letters 26 IAFF Announces Media Awards 9 Contest Winners n 10 Noteworthy News Recognizing affiliates for their best work in communicating with their members, elected n 30 Local Scene officials and the public.