DIATOPY of COMPLEMENT-Pu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

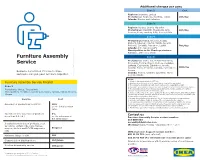

Assembly Leaflet AES ACS

Additional charges per zone Υπηρεσία Zone 2 Cost Regions: Ioannina, Larissa συναρμολόγησης επίπλων Prefectures: Magnesia, Karditsa, Trikala 20€/day Islands: Rhodes and Salamina Zone 3 Regions: Achaea, Chania, Heraklion Prefectures: Chalkidiki, Thesprotia, Arta, 40€/day Preveza, Pieria, Imathia, Pella, Serres, Kilkis Zone 4 Prefectures: Drama, Grevena, Kozani, Kastoria, Rhodope, Kavala, Xanthi, Boeotia, Phthiotis, Corinthia, Rethymno, Lasithi 70€/day © Islands: Argo-Saronic Gulf's Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2018 B.V. Inter IKEA Systems Municipalities in the Chania prefecture: Kantanos, Selino and Sfakia Furniture Assembly Zone 5 Prefectures: Corfu, Ilia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Service Evrytania, Florina, Phocis, Euboea, Cyclades, Lefkada, Cephalonia, Zakynthos, Argolis, Arcadia, Evros, Messinia, Laconia, Dodecanese, 100€/day Because sometimes it’s nice to have Lesbos Islands: Thasos, Cythera, Sporades, North someone else put your furniture together. Aegean islands Notes: 1. All above listed prices include VAT 24%. Furniture Assembly Service Pricelist 2. Furniture must be located to the space where they will be assembled. 3. The charge for an additional visit, due to customer’s responsibility, is 25€. Zone 1 4. Consumer is not obliged to pay if the notice of payment is not received (receipt-invoice). Prefectures: Attica, Thessaloniki 5. The assembly charge for products purchased from the As-Is Department or with a discount is calculated based on their initial value. Municipalities: Heraklion, Ioannina, Komotini, Larissa, Patras, Rhodes, 6. Disassembly service in the store, applies for the stores IKEA Airport, IKEA Kifissos, IKEA Chania Thessaloniki and IKEA Ioannina. Maximum waiting time is 2 hours. Service is available until 2 hours before closing time of the store. -

Government Spending on Regional Public Services in Greece: Spatial Distribution of Their Evolution Before and During the Financial Crisis

Government spending on regional public services in Greece: Spatial distribution of their evolution before and during the financial crisis. Anastasiou Eugenia1,*, Theodossiou George2, Thanou Eleni3 1 PhD Candidate, Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Greece 2Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, TEI of Thessaly 3Lecturer, Graduate Program on Banking, Hellenic Open University *Corresponding author: [email protected], Tel +30 24210 74433 Abstract Greece is still caught in a prolonged recession, which started in 2008. As a result, the economy continues to shrink, which has direct repercussions on the level of private and public consumption as well as on the level government's functions. The present paper attempts to record and depict spatially the evolution of the per capita public spending of the central government on regional services. The specific category of public spending represents a measure of relative welfare as well as a measure of regional development. For the purposes of the research we applied analytical methods such as descriptive statistics and we used specialized mapping analysis programs and geographical information systems (GIS). The evolution over time is observed on the basis of the annual percentage changes of per capita spending. The period of analysis is 2008-2013 and it includes years before the manifestation of the economic crisis as well as the years of the crisis' peak. The thematic maps that were constructed on the basis of the data clearly demonstrate that government spending on the regions was dramatically reduced during the crisis while the period during which the tightening of fiscal policy had a direct impact on the regions stands out. -

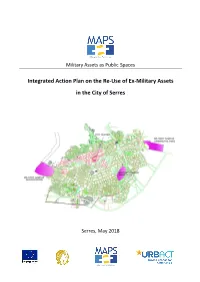

SWOT Analysis

Military Assets as Public Spaces Integrated Action Plan on the Re-Use of Ex-Military Assets in the City of Serres Serres, May 2018 Contents Chapter 1: Assessment ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 General info ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 Location, history, key demographics, infrastructure, economy and employment ........................... 4 1.1.2 Planning, land uses and cultural assets in the city ........................................................................... 8 1.2 Vision of Serres ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.3 The military camps in Serres .................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.1 Project Area 1: Papalouka former military camp ............................................................................ 14 1.3.2 Project area 2: Emmanouil Papa former military camp.................................................................. 18 1.3.3 The Legislative Framework ............................................................................................................. 21 1.3.4 The particularities of the military assets in Serres .......................................................................... 22 -

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues Paris Tsartas University of the Aegean, Michalon 8, 82100 Chios, Greece The paperanalyses two issuesthat have characterised tourism development inGreek insularand coastalareas in theperiod 1970–2000. The firstissue concerns the socioeco- nomic and culturalchanges that have taken place in theseareas and ledto rapid– and usuallyunplanned –tourismdevelopment. The secondissue consists of thepolicies for tourismand tourismdevelopment atlocal,regional and nationallevel. The analysis focuseson therole of thefamily, social mobility issues,the social role of specific groups, and consequencesfor the manners, customs and traditionsof thelocal popula- tion.It also examines the views and reactionsof localcommunities regarding tourism and tourists.There is consideration of thenew productive structuresin theseareas, including thedowngrading of agriculture,the dependence of many economicsectors on tourism,and thelarge increase in multi-activityand theblack economy. Another focusis on thecharacteristics of masstourism, and on therelated problems and criti- cismsof currenttourism policies. These issues contributed to amodel of tourism development thatintegrates the productive, environmental and culturalcharacteristics of eachregion. Finally, the procedures and problemsencountered in sustainabledevel- opment programmes aiming at protecting the environment are considered. Social and Cultural Changes Brought About by Tourism Development in the Period 1970–2000 The analysishere focuseson three mainareas where these changesare observed:sociocultural life, productionand communication. It should be noted thata large proportionof all empirical studies of changesbrought aboutby tourism development in Greece have been of coastal and insular areas. Social and cultural changes in the social structure The mostsignificant of these changesconcern the family andits role in the new ‘urbanised’social structure, social mobility and the choicesof important groups, such as young people and women. -

ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS “Archaeological Tourism in Greece

UNIVERSITY OF THE PELOPONNESE ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS (R.N. 1012201502004) DIPLOMA THESIS: “Archaeological tourism in Greece: an analysis of quantitative data, determining factors and prospects” SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara EXAMINATION COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikolaos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara - Dr. Nikolaos Platis ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ, MARCH 2017 Abstract . For many decades now, Greece has invested a lot in tourism which can undoubtedly be considered the country’s most valuable asset and “heavy industry”. The country is gifted with a rich and diverse history, represented by a variety of cultural heritage sites which create an ideal setting for this particular type of tourism. Moreover, the variations in Greece’s landscape, cultural tradition and agricultural activity favor the development and promotion of most types of alternative types of tourism, such as agro-tourism, religious, sports and medicinal tourism. However, according to quantitative data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, despite the large number of visitors recorded in state-run cultural heritage sites every year, the distribution pattern of visitors presents large variations per prefecture. A careful examination of this data shows that tourist flows tend to concentrate in certain prefectures, while others enjoy little to no visitor preference. The main factors behind this phenomenon include the number and importance of cultural heritage sites and the state of local and national infrastructure, which determines the accessibility of sites. An effective analysis of these deficiencies is vital in order to determine solutions in order to encourage the flow of visitors to the more “neglected” areas. The present thesis attempts an in-depth analysis of cultural tourism in Greece and the factors affecting it. -

Report to the Greek Government on the Visit to Greece Carried out By

CPT/Inf (2020) 15 Report to the Greek Government on the visit to Greece carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 28 March to 9 April 2019 The Greek Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2020) 16. Strasbourg, 9 April 2020 - 2 - CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 4 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 8 A. The visit, the report and follow-up.......................................................................................... 8 B. Consultations held by the delegation and co-operation encountered .................................. 9 C. Immediate observations under Article 8, paragraph 5, of the Convention....................... 10 D. National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) ............................................................................... 11 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED .............................. 12 A. Prison establishments ............................................................................................................. 12 1. Preliminary remarks ........................................................................................................ 12 2. Ill-treatment .................................................................................................................... -

The Fourth Season of Danish-Greek Archaeological Fieldwork on the Lower Acropolis of Kalydon in Aitolia Has Now Been Underway for Two Weeks

The fourth season of Danish-Greek archaeological fieldwork on the Lower Acropolis of Kalydon in Aitolia has now been underway for two weeks. The fieldwork is a collaboration between the Danish Institute at Athens and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Aetolia-Acarnania and Lefkada in Messolonghi and directed by Dr. Søren Handberg, Associate Professor at the University of Oslo and the Ephor Dr. Olympia Vikatou. This year work focuses on the completion of the excavation of the Hellenistic house with a courtyard, which was first identified in 2013. During the past two weeks, the excavations have already produced significant new finds. In one room, where a collapsed roof has preserved the content of the room intact, fifteen small nails have been identified, which presumably originally belonged to a small wooden box kept inside the room. Last Friday, an Ionic column drum was excavated in an area that might be part of the courtyard of the house. A considerable amount of Roman Terra Sigillata pottery of the Augustan period has also been found, which is surprising since the ancient literary sources suggest that the city was abandoned at this time. The ongoing topographical survey of the entire ancient city has revealed approximately thirty previously undocumented structures, one of which might be a larger public building in the eastern part of the city. This year’s team comprises 50 people from Greece, Denmark, and Norway including students of archaeology from Aarhus University, the University of Copenhagen and the University of Oslo. The project is grateful to the Carlsberg Foundation for the continued financial support, which facilitates the fieldwork that is essential for establishing the ancient history of Kalydon and the region of Aitolia. -

Greece I.H.T

Greece I.H.T. Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) GREECE Visa: Greece is a signatory of the 1995 Schengen Agreement Duty Free: goods permitted: 800 cigarettes or 50 cigars or 100 cigarillos or 250g of tobacco, 1 litre of alcoholic beverage over 22% or 2 litres of wine and liquers, 50g of perfume and 250ml of eau de toilet. Health: a yellow ever vaccination certificate is required from all travellers over 6 months of age coming from infected areas. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS ACHARAVI KERKYRA BEIS BEACH HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63913 (0663) 63991 CENTURY RESORT 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63401-4 (0663) 63405 GELINA VILLAGE 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 64000-7 (0663) 63893 [email protected] IONIAN PRINCESS CLUB-HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63110 (0663) 63111 ADAMAS MILOS CHRONIS HOTEL BUNGALOWS 848 00 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22226, 23123 (0287) 22900 POPI'S HOTEL 848 01 Adamas, on the beach Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22286-7, 22397 (0287) 22396 SANTA MARIA VILLAGE 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22015 (0287) 22880 Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++30 VAMVOUNIS APARTMENTS 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE Greek National Tourism Organisation: Odos Amerikis 2b, 105 64 Athens Tel: TEL: (0287) 23195 (0287) 23398 (1)-322-3111 Fax: (1)-322-2841 E-mail: [email protected] Website: AEGIALI www.araianet.gr LAKKI PENSION 840 08 Aegiali, on the beach Amorgos AEGIALI AMORGOS Capital: Athens Time GMT + 2 GREECE TEL: (0285) 73244 (0285) 73244 Background: Greece achieved its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1829. -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Pdf Brochure

Wonderful Villa with amazing garden - 3 bedrooms on the beach Summary 1 Description 3 bedroom ground floor villa in a beautiful green area of 4 acres with many species of trees and plants, besides to a beautiful sandy beach. The villa has a patio, BBQ and private parking. Available canoe. The villa consists of three bedrooms with double bed, fully equipped spacious kitchen-dining-living room with sofa bed, TV, washing machine, air condition, WC / SH, porches overlooking the garden and sea. Free Wi Fi. Distance from Lefkimmi, shops and amenities: 1,800 m. Distance from beach: In front of the beach. LEFKIMMI (40 km from Corfu Town) is a beautiful small town to south-east of the island. It was built, perhaps, in 1500 a.c., but the historical roots reach up to 4o B.C. century. It still keeps up, in a great deal, the style and color of the previous centuries. The small navigable river, the plains and forests which surround it, as well as the golden beaches, are some of its characteristics. To the south of LEFKIMMI we meet the resorts of AGHIOS PETROS (3km) and KAVOS (5 km). To the west we meet the picturesque CHORIA and to the north, PERIVOLI, VITALADES, ARGYRADES, BUKARI, PETRITI etc. FERRY BOAT: LEFKIMMI- IGOUMENITSA (1 hour) DAILY TRIPS: from LEFKIMMI Port by boat to the beautiful little islands of PAXOS and ANTIPAXOS. General • Washing Machine • Linens Provided • A/C or climate control • Soap/Shampoo Provided • Iron • Housekeeping Optional • Hair dryer • Towels Provided Property Features • Secure parking space • Parking • Mountain Views