The Turbulent 2010S: a Historical Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASA NEWS African Studies Association Volume XLII No.3 July 2009

V V V V ASA NEWS African Studies Association Volume XLII no.3 July 2009 ASA News, Vol. XLII, No. 3, African In This Issue July 2009 V ISSN 1942-4949 VVV Studies Editor: Association From the Executive Director..................2 Carol L. Martin, PhD New Members.....................................3 Associate Editor, Designer and Typesetter: Kristina L. Carle Membership Rates...............................4 Published online three times a year by the Member News.....................................4 African Studies Association. Submissions and In Memoriam......................................5 advertisements for the ASA News should be sent to [email protected] as a PDF fi le. Obituaries...........................................5 Deadlines for submissions and advertisements are December 1, March 1, and June 1. 2009 ASA Election Results....................6 Join the ASA.......................................7 OFFICERS President: Paul Tiyambe Zeleza (U of Illinois-Chicago) Contributors to the Endowment.............8 Vice President: Charles Ambler (U of Texas at El Paso) Coordinate Organization Corner.............9 Past President: Aliko Songolo (U of Wisconsin-Madison) Executive Director: Carol L. Martin (Rutgers U) Annual Meeting Key Information..........12 Treasurer: Scott Taylor (Georgetown U) Call for Submissions...........................16 DIRECTORS Serving Until 2009 Grants and Fellowships.......................17 Jane Guyer (Johns Hopkins U) Babatunde Lawal (Virginia Commonwealth U) Recent Doctoral Dissertations..............20 -

ASA NEWS African Studies Association Volume XLII No.1 January 2009

V V V V ASA NEWS African Studies Association Volume XLII no.1 January 2009 ASA News, Vol. XLII, No. 1, African In This Issue January 2009 V ISSN 1942-4949 VVV Studies Editor: Association From the Executive Director..................2 Carol L. Martin, PhD From the President..............................3 Associate Editor, Designer and Typesetter: New Members.....................................4 Kristina L. Carle Member News.....................................4 Membership Rates...............................4 Published online three times a year by the In Memoriam......................................5 African Studies Association. Submissions and advertisements for the ASA News should be sent Join the ASA.......................................7 to [email protected] as a PDF fi le. Contributors to the Endowment.............8 Deadlines for submissions and advertisements are 50 Year Anniversaries Campaign............8 December 1, March 1, and June 1. 2008 Awards and Prizes.....................12 Coordinate Organization Corner...........14 OFFICERS 2008 ASA Election Results...................17 President: Paul Tiyambe Zeleza (U of Illinois-Chicago) Vice President: Charles Ambler (U of Texas at El Paso) Annual Meeting Key Information..........18 Past President: Aliko Songolo (U of Wisconsin-Madison) Call for Proposals...............................22 Executive Director: Carol L. Martin (Rutgers U) Treasurer: Scott Taylor (Georgetown U) Annual Meeting Theme.......................26 Style Guide.......................................30 -

Malawi Makes History: the Opposition Wins Presidential Election Rerun

CODESRIA Bulletin Online, No. 4, July 2020 Page 1 Online Article Malawi Makes History: The Opposition Wins Presidential Election Rerun This piece first appeared on the author’s linked-in page June( 28, 2020) a n d has been republished here with his permission n Saturday, June 27, 2020 In the struggles for democratiza- Malawi became the first Paul Tiyambe Zeleza tion, for the “second independ- Ocountry in Africa where a Vice Chancellor ence” in the 1980s and early 1990s, presidential election rerun was won United States International Malawi’s political culture was by the opposition. On February 3, University, Kenya buoyed by the emergence of strong 2020 Malawi became the second social movements. These move- country on the continent where the ments coalesced most prominently Constitutional Court nullified the power since 2004, save for a brief around the Public Affairs Commit- presidential election of May 21, interlude. The two-year interval was tee and the Human Rights Defend- 2019 because of widespread, sys- the presidency of Joyce Banda fol- ers Coalition. Formed in 1992 as a tematic, and grave irregularities lowing the death of Bingu wa Muth- pressure group of religious com- and anomalies that compromised arika in April 2012 and the election munities and other forces, PAC the right to vote and the democratic of Peter Mutharika, the late Bingu’s became a highly respected and in- choice of citizens. The first country brother, in May 2014. fluential political actor. While PAC was Kenya where the presidential functioned as a civil interlocutor election of August 8, 2017 was an- This reflects, secondly, Malawi’s for democracy, the HRDC flexed nulled by the Supreme Court on political culture of collective na- its political muscles in organizing September 1, 2017. -

In Search of African Diasporas 00 Zeleza Final 3/1/12 9:22 AM Page Ii

00 zeleza final 3/1/12 9:22 AM Page i In Search of African Diasporas 00 zeleza final 3/1/12 9:22 AM Page ii Carolina Academic Press African World Series Toyin Falola, Series Editor Africa, Empire and Globalization: Essays in Honor of A. G. Hopkins Toyin Falola, editor, and Emily Brownell, editor African Entrepreneurship in Jos, Central Nigeria, 1902 –1985 S.U. Fwatshak An African Music and Dance Curriculum Model: Performing Arts in Education Modesto Amegago Authority Stealing: Anti-Corruption War and Democratic Politics in Post-Military Nigeria Wale Adebanwi The Bukusu of Kenya: Folktales, Culture and Social Identities Namulundah Florence Contemporary African Literature: New Approaches Tanure Ojaide Contesting Islam in Africa: Homegrown Wahhabism and Muslim Identity in Northern Ghana, 1920 –2010 Abdulai Iddrisu Democracy in Africa: Political Changes and Challenges Saliba Sarsar, editor, and Julius O. Adekunle, editor 00 zeleza final 3/1/12 9:22 AM Page iii Diaspora and Imagined Nationality: USA-Africa Dialogue and Cyberframing Nigerian Nationhood Koleade Odutola Food Crop Production, Hunger, and Rural Poverty in Nigeria’s Benue Area, 1920 –1995 Mike Odugbo Odey Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business N. Oluwafemi Mimiko In Search of African Diasporas: Testimonies and Encounters Paul Tiyambe Zeleza Intercourse and Crosscurrents in the Atlantic World: Calabar-British Experience, 17th –20th Centuries David Lishilinimle Imbua Pioneer, Patriot, and Nigerian Nationalist: A Biography of the Reverend -

African Studies and Its Configurations: Histories, Challenges and Opportunities

African Studies and its Configurations: Histories, Challenges and Opportunities Keynote Delivered at a Workshop on Reconfiguring African Studies, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya, 19-21 FEBRUARY 2020 Prof. Enocent Msindo (PhD, Cambridge), Director, African Studies Centre, Rhodes University, RSA (DRAFT PAPER, NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PRIOR AUTHORITY OF THE AUTHOR) Abstract: Developed in response to the changing Western imperial interests on the continent, African studies as a field of research has predominantly mirrored the evolving Western geo-political and economic interests in Africa. Although the radical histories of the 1960s and subsequent work, (including the work of CODESRIA and other independent scholars) tried to critique some colonial tropes about the continent, they did not do enough. Radical nationalist historiographies were in fact a part of the broader Western political decolonization politics associated with receding empires. This historical paper traces the emergence, growth and development of African studies in the Global North and subsequently in Africa since the colonial era. It argues that regardless of the growing diversity of specialisations on various issues on African studies in the new African universities, foundational assumptions and stereotypes about the continent and ‘the African’ have not quite abated and have not been challenged enough. In most cases, contemporary analysis of Africa, particularly since the 1980s have continued to mirror the ‘moving walls’ of imperial and neo-colonial interests. It is therefore not surprising that the bulk of research done in Africa are deeply Afropessimist in nature and focus on the state – its poor economic performance, bad governance, and related issues. Unsurprisingly, no solutions are proffered as the intention is not to do so, but to justify the Afropessimist narrative which centres on the assumption that since the retreat of colonial regimes, the continent has increasingly become a site of despair. -

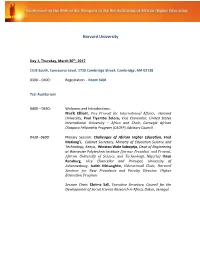

Projects at Harvard

Harvard University Day 1, Thursday, March 30th, 2017 CGIS South, Concourse Level, 1730 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 0300 – 0400: Registration – Room S001 Tsai Auditorium 0400 – 0430: Welcome and Introductions: Mark Elliott, Vice Provost for International Affairs, Harvard University, Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, Vice Chancellor, United States International University – Africa and Chair, Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program (CADFP) Advisory Council 0430 –0600: Plenary Session: Challenges of African Higher Education, Fred Matiang’i, Cabinet Secretary, Ministry of Education Science and Technology, Kenya, Winston Wole Soboyejo, Dean of Engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (former President and Provost, African University of Science and Technology, Nigeria) Ihron Rensburg, Vice Chancellor and Principal, University of Johannesburg, Judith McLaughlin, Educational Chair, Harvard Seminar for New Presidents and Faculty Director, Higher Education Program Session Chair: Ebrima Sall, Executive Secretary, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, Dakar, Senegal. Day 2, Friday, March 31st, 2017: Harvard Art Museums, Deknatel Hall – Lower Level (Enter on Broadway Street between Prescott and Quincy Streets) 8:00 – 9:15 AM: Panel Discussion: The Future of African Universities: Policy Directions – Berhanu Abegaz, Director, African Academy of Sciences , Alexandre Lyambabaje, Executive Secretary, Inter- University Council for East Africa, Phillip Clay, Professor and former Chancellor Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Board member, Kresge Foundation (former Board member, MasterCard Foundation) Kassa Belay, Rector, the Pan African University Session Chair: Pinkie Mekgwe, Executive Director, Division for Internationalization, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. 9:15 – 10:15 AM: Keynote Speech: H.E Dr Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete. Former President United Republic of Tanzania and Chancellor, University of Dar es Salaam. -

INTERNATIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION Number 76: Summer 2014

INTERNATIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION Number 76: Summer 2014 THE BOSTON COLLEGE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION International Higher Education International Issues is the quarterly publication of 2 Student Activism: A Worldwide Force the Center for International Philip G. Altbach and Manja Klemencic Higher Education. American Themes in Global Perspective The journal is a reflection of 4 Research Universities: American Exceptionalism? the Center’s mission to en- Henry Rosovsky courage an international per- 6 Demographics and Higher Education Attainment spective that will contribute to Arthur M. Hauptman enlightened policy and prac- Internationalization tice. Through International 7 Converging or Diverging Global Trends? Higher Education, a network Eva Egron-Polak of distinguished international 9 International Students: UK Drops the Ball scholars offers commentary Simon Marginson and current information on Private Higher Education key issues that shape higher 11 Private Higher Education in the UK: Myths and Realities education worldwide. IHE is Steve Woodfield published in English, Chinese, 13 US For-Profit Higher Education Russian, Portuguese, and Elizabeth Meza and William Zumeta Spanish. Links to all editions Africa Focus can be found at www.bc.edu/ cihe. 14 Inside African Private Higher Education Louise Morley 16 African Academic Diaspora Kim Foulds and Paul Tiyambe Zeleza China: New Directions 17 Reforming the Gaokao Gerard A. Postiglione 19 Systematic Changes Qiang Zha and Chuanyi Wang Countries and Regions 20 Graduate Education in Malaysia and Thailand Chiao-Ling Chien and David W. Chapman 22 Russian Examinations: Problems and Perspectives Elena Denisova-Schmidt and Elvira Leontyeva 23 The International Higher Education Reader Survey Ariane de Gayardon and David A. -

Africa and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Defining a Role for Research Universities

Second Biennial Conference Africa and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Defining a Role for Research Universities University of Nairobi 18-20 November 2019 Programme Day 1: Monday, 18 th November 2019 (Conference Opening: Chandaria Auditorium) 9.00 am Introductory Remarks: Professor Madara Ogot , Deputy Vice Chancellor (Research) University of Nairobi and Chair of Local Organising Committee Professor Ernest Aryeetey , ARUA Secretary-General Welcome Remarks: Professor Isaac Mbeche , Acting Vice Chancellor, University of Nairobi Brief Remarks: Professor Idowu Olayinka , Vice Chancellor, University of Ibadan and Board Chair, ARUA 9.20 am First Keynote Address: Professor Zeblon Vilakazi , Deputy Vice Chancellor (Research and Innovation), University of the Witwatersrand 9.50 am Opening of Conference: Hon. Prof. George Magoha , Cabinet Secretary Ministry of Education, Republic of Kenya 10.00 am Tea/Coffee Break 10.30 am First Plenary Session: Universities and the Fourth Industrial Revolution: (Chandaria Auditorium) Any Best Practices? 1 (Chair: Professor Barnabas Nawangwe , Vice Chancellor, Makerere University) 1. Professor Margaret J. Dallman , Imperial College, London; The STEM and Skills Drivers of the Fourth Industrial Revolution - An International Perspective 2. Professor Njuguna N’dungu , Executive Director, African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi, Kenya; The Challenges and Opportunities of Technological Change and the Fourth Industrial Revolution in Africa 3. Professor Jan Palmowski, Guild of European Research Universities, Preparing -

Ezekiel Kalipeni CV

1 Ezekiel Kalipeni CV CURRICULUM VITAE EZEKIEL KALIPENI (Ph.D.) Professor of Geography Department of Geography, 220 Davenport Hall, MC-150 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 607 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801. Tel. (217)244-7708, Cell: (217)898-4694, Fax (217)244-1785 e-mail: [email protected] PERSONAL DETAILS Name : Ezekiel Kalipeni (Ph.D.), Professor of Geography University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Address : Home: 1607 Sangamon Drive, Champaign, IL 61821 EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS 1980-1986 : University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Geography, 203 Saunders Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, U.S.A. Obtained the degrees of M.A. (1982) and Ph.D. (1986) in Population and Environmental Studies, Medical Geography, and Third World Development Issues 1975-1979 : University of Malawi, Chancellor College, P.O. Box 280, Zomba, Malawi; Obtained the degree of Bachelor of Social Science with distinction in Human/Social Geography, Statistics and Clinical Psychology. 1970-1975 : St. Kizito Catholic Seminary, P.O. Malilana, Dedza, Malawi; Obtained the Malawi Certificate of Education, "O" Levels with Distinction, 1975. Took courses in English, Chichewa Language, Mathematics, Geography, History, Physical Science and Bible Knowledge. 1967-1970 : St. Paul's Catholic Seminary, P.O. Mitundu, Lilongwe, Malawi; Obtained the Primary School Leaving Certificate, 1970. WORK EXPERIENCE 2009 - Professor of Geography, Department of Geography, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 2009-2011 Program Director, Geography and Spatial Sciences Program, National Science Foundation, Arlington, Virginia. 2000-2009: Associate Professor of Geography in the Department of Geography, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2001-2002: Interim Director, Center for African Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 2 Ezekiel Kalipeni CV 1994-2000: Assistant Professor of Geography in the Department of Geography, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

Mandela's Long Walk with African History – Part 2

5/3/2017 Africa at LSE – Mandela’s Long Walk with African History – Part 2 Mandela’s Long Walk with African History – Part 2 Paul Tiyambe Zeleza examines how Nelson Mandela epitomised all the key phases, dynamics and ideologies of African nationalism in the 20th century. This is the second of three posts in which the historian posits South Africa’s founding father alongside some of the major events of the 20th century. Click through to read the first article of this series The decolonisation drama started in Egypt in 1922 with the restoration of the monarchy and limited internal selfgovernment and finally ended in 1994 with the demise of apartheid in South Africa. In the long interregnum, decolonisation unfolded across the continent, reaching a crescendo in the 1950s and 1960s; in 1960 alone, often dubbed the year of African independence, 17 countries achieved their independence. The colonial dominoes began falling from North Africa (Libya 1951) to West Africa (Ghana 1957) to East Africa (Tanzania 1961) before reaching Southern Africa (Zambia and Malawi 1964). The settler laagers of Southern Africa were the last to fall starting with the Portuguese settler colonies of Angola and Mozambique in 1974, followed by Rhodesia in 1980, and Namibia in 1990. South Africa, the largest and mightiest of them all, finally met its rendezvous with African history in 1994. Nelson Mandela is cherished because of his and his country’s long walk with African history. Mandela embodied all the key phases, dynamics and ideologies of African nationalism from the period of elite nationalism before the Second World War when the nationalists made reformist demands on the colonial regimes, to the era of militant mass nationalism after the war when they demanded independence, to the phase of armed liberation struggle. -

Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, Manufacturing African Studies and Crises Volume a Modem Economic History of Africa1~Urrent1y Director Of

Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, Manufacturing African Studies and Crises (Dakar: CODESRI.A, Book Series, 1997). A citizen of Malawi and graduate of Dalhousie University in Canada, economic historian by trade-author of a critically-acclaimed, two volume A Modem Economic History ofAfrica 1~urrent1y director of African Studies at the University of lllinois, Paul Tiyambe Zeleza is a man of many talents. He is a true African Renaissance man and Honnete Homme du 21 erne siecle. Novelist, essayist and literary critic, Zeleza also ventures effortlessly into many other disciplines such as history, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, economics and political science, as his erudite and massive Manufacturing African Area Studies and Cris~mprising no less than 23 chapters, 531 pages of text and some 2,000 bibliographic entries--amply demonstrates. Yet in spite of his impressive literary and academic achievements and substantial publication record, Zeleza was, until recently, relatively unknown in Africanist circles. This was due to a conjunction of factors: his versatility and multidiscipilinarity (making it difficult to "pigeon-hole" him in any particular discipline), his relative geographically eccentricity--evolving as he was first in African universities, then in the rarified atmosphere of Canadian African studies, and the fact that his Dakar-based publisher, CODESRIA. is not widely distributed outside of Africa. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the November 1995 Orlando annual meeting of the United States-based African Studies Association was the first one be ever attended. Inspired by the debate around Philip Curtin's controversial piece "Ghettoizing African History"2 and the related session on "Ghettoizing African Studies," Zeleza resolved to address bead-on the question of representation in the study of Africa and concluded that Africanist discourse-by which he means "the entire intellectual enterprise of producing knowledge based on a western epistemological order in which both educated Africans and non Africans are engaged," (p. -

The Roots of African Conflicts: the Causes and Costs

nhema&zeleza 00intro-pref 24/9/07 10:12 Page 1 Introduction The Causes & Costs of War in Africa From Liberation Struggles to the ‘War on Terror’ PAUL TIYAMBE ZELEZA Violent conflicts of one type or another have afflicted Africa and exacted a heavy toll on the continent’s societies, polities and economies, robbing them of their developmental potential and democratic possibilities. The causes of the conflicts are as complex as the challenges of resolving them are difficult. But their costs cannot be in doubt, nor the need, indeed the urgency, to resolve them, if the continent is to navigate the twenty-first century more successfully than it did the twentieth, a century that was marked by the depredations of colonialism and its debilitating legacies and destructive post- colonial disruptions. The magnitude and impact of these conflicts are often lost between hysteria and apathy – the panic expressed among Africa’s friends and the indifference exhibited by its foes – for a continent mired in, and supposedly dying from, an endless spiral of self-destruction.1 The distor- tions that mar discussions and depictions of African conflicts are rooted in the long-standing tendency to treat African social phenomena as peculiar and pathological, beyond the pale of humanity, let alone rational explana- tion. Yet, from a historical and global perspective, Africa has been no more prone to violent conflicts than other regions. Indeed, Africa’s share of the more than 180 million people who died from conflicts and atrocities during the twentieth century is relatively modest: in the sheer scale of casualties there is no equivalent in African history to Europe’s First and Second World Wars, or even the civil wars and atrocities in revolutionary Russia and China.