Psychoanalysis and Tango: Complex Arts of Grief Therapy Psychoanalysis and Tango Dancing During This Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond If you walk on and on, you get to your destination. If you question much, you get your information. If you do not sleep and idle, you preserve your life! (Maung Htin Aung 1959:87) So go the three lines of wisdom offered to the lazy student Maung Pauk Khaing in the well- known eponymous folk tale. A group of impoverished village youngsters, led by their teacher Daw Khin Thida, adapted the tale in 2007 in their first attempt to perform a play. From a well-to-do family that does not understand her philanthropic impulses, Khin Thida, an English teacher by profession, works at her free school in Insein, a suburb of Yangon (Rangoon) infamous for its prison. The shy students practiced first in Burmese for their village audience, and then in English for some foreign donors who were coming to visit the school. Khin Thida has also bought land in Bagan (Pagan) and is building a culture center there, hoping to attract the street children who currently pander to tourists at the site’s immense network of temples. TDR: The Drama Review 53:1 (T201) Spring 2009. ©2009 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram.2009.53.1.93 by guest on 02 October 2021 I first met Khin Thida in 2005 at NICA (Networking and Initiatives for Culture and the Arts), an independent nonprofit arts center founded in 2003 and run by Singaporean/Malaysian artists Jay Koh and Chu Yuan. -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

The Intimate Connection of Rural and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works Spanish Faculty Works Spanish 2018 Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi Vila Swarthmore College, [email protected] P. Vila Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Julia Chindemi Vila and P. Vila. (2018). "Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century". Sound, Image, And National Imaginary In The Construction Of Latin/o American Identities. 39-90. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish/119 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 2 Another Look at the History of Tango The Intimate Connection of Rural ·and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi and Pablo Vila Since the late nineteenth century, popular music has actively participated in the formation of different identities in Argentine society, becoming a very relevant discourse in the production, not only of significant subjectivities, but also of emotional and affective agencies. In the imaginary of the majority of Argentines, the tango is identified as "music of the city," fundame ntally linked to the city of Buenos Aires and its neighborhoods. In this imaginary, the music of the capital of the country is distinguished from the music of the provinces (including the province of Buenos Aires), which has been called campera, musica criolla, native, folk music, etc. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Analysis of the Crossover

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Analysis of the Crossover Between Ballroom and Ballet in Choreographic Works THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER FINE ARTS in Dance by Chanel Kostich Thesis Committee: Professor Alan Terricciano, Chair Associate Professor Tong Wang Assistant Professor Vitor Luiz 2020 © 2020 Chanel Kostich TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Dance Autobiography 3 CHAPTER 2: Synopsis & Timeline of the Three Works 7 NYC Ballet: “Vienna Waltzes” 7 Grupo Corpo: “Grande Waltz” 11 Tango Pasión: “Argentine Tango Duet” 16 CHAPTER 3: Contextualizing the Interview with Rodrigo Pedernerias 20 CHAPTER 4: Heat of the Night: A Choreographic Thesis Film 22 Reflection of Thesis Project 30 Appendix 1: MethodoLogy Movement 32 American Smooth Tango Argentine Tango Ballet in Tango Pasión Bolero, Ballet, and Argentine Tango Viennese Waltz Appendix 2: Interview with Rodrigo Pederneiras 39 Appendix 3: Collaborative Design, Copyright Information, Contents of the Music 50 Works Cited 54 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to start by expressing immense gratitude for my thesis chair, Alan Terricciano. Thank you for your encouragement to experiment and be creative within this research process and for your continued patience as we worked through those choices together. Our discussions were always meaningful and impactful to this work, as weLL as to me as a graduate student. I appreciate your kindness, advice, and enthusiasm towards my creative work as we coLLaborated throughout this research process. I would like to thank my thesis committee members Professor Tong Wang and Professor Vitor Luiz for your encouragement and guidance. -

Performance Tango Or Tango Milonguero ?

Performance Tango or Tango Milonguero ? Collected notes : Susana Miller: Two styles of Argentine tango, performance and milonguero, bring about a controversy in the dance community. Some attribute a false dichotomy between these styles. False because, in reality, they are complimentary. In a certain aspect, performance tango and milonguero tango are two sides of the same coin. The Milonguero, or "close embrace" style is danced in the crowded clubs of Buenos Aires. It evolved to compensate for large numbers of couples dancing in limited space. The Milonguero style is a rich and complex form of body signals and incorporates deep respect for the music and its varied rhythms. The result is a form of Tango that allows for simplicity of steps while encouraging a natural connection between the dancers. However, tango is known throughout the world because of performance tango. The beauty and splendor of its figures are spread by TV and on the stages of theaters across great distances to far away places. In this tango the couple separates in order to execute complicated figures and steps that have more visual appeal. They separate because it would be difficult to see the "closed" tango in a large theater of 500 or more people. The body work, particularly the leg motions, would not engender great interest. In the performance tango the steps are based on milonguero style, but are enlarged and embellished, and become choreographies that cross the stage diagonally, creating displays and making full use of the ample space available. The tango is known throughout the world thanks to the artists, very fine and expert dancers, and thanks to their inspiration and the hours of daily work that they devoted to their talent. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Tango Fundamentals (Level 2) - Course Syllabus

Tango Fundamentals (Level 2) - Course Syllabus Through consolidation and refinement of the fundamental elements covered in Level 1, and the introduction of some new concepts, this course will enable you to develop as a more competent and confident social dancer. For those that wish to, the course will also explore dancing in close embrace. The course continues over three ten-week terms. Course Pre-requisite: Completion of the Level 1 Course Syllabus offered by Suffolk Tango or equivalent tuition. If in doubt, please contact the course teachers via the Suffolk Tango website. During the whole course you will learn: To develop your skills in dancing using close embrace as well as in open embrace. To develop more intricate and complex footwork to enhance the styling of the basic elements. To adapt the fundamentals to improve your floor-craft and navigation on the dance floor. To make changes of direction – ‘alterations’. To develop musicality in the dance, in particular the use of double time and syncopation. Linear Sacadas (interruption of the free leg) Fun ‘foot and leg play’ –barridas (foot sweeps), and ganchos (leg hooks). More about the Tango musical form, styles, composers and orchestras. Autumn Term (10 weeks) The Close Embrace: Building confidence in dancing in close embrace. Understanding the difference between open and close embrace – their relative strengths and weaknesses. Finding the connection. Walking with ease and confidence in two, three and four-track. Moving between open and close embrace within the dance. Adapting the basic elements learned in open embrace to work in close embrace. Taking the opportunities of close embrace to develop a compact and intimate (milonguero) style. -

BREEZE Brean 2018

www.cerocescape.com PASSPORT TO DANCE DIFFERENT DANCE STYLES Welcome TAUGHT MANY VARIED AND EXCITING WORKSHOPS OVER 40 For over 12 years, Ceroc have populated huge, fun-flled dance weekenders that attract between 1500-2200 guests. To get that HOURS OF FREESTYLE many like minded people continually congregating on dance weekenders is a testimony to the passion of our dance community. There are over 40 classes scheduled this weekend including different dance styles and 4 rooms for freestyle offering various TEACHERS FROM ALL OVER THE genres of music to appeal to everyone. UK SILC EUROPEAN NEO-BLUES We urge you to dip your toes into everything we have to offer, and CHAMPIONSHIPS 2018 DJS FROM try something you've never tried before. Whether it's learning a new dance style, freestyling to a completely different genre of music or FAR & WIDE MASSAGE venturing into an unknown DJ's set, our weekends can open your SWIMMING WORKSHOP DVDS TO eyes to brand new adventures. You may even discover a new TAKE HOME MASTERCLASSES found passion to take home with you! At this event, we celebrate the return of the European Neo-Blues SELECTION OF DANCE SHOES Championships. Whether you wish to compete or simply sit back and enjoy the spectacle, our Dance With A Stranger, Open and AND CLOTHING ON SALE Masters Invitational categories are sure to excite and inspire. Who will be crowned our 2018 Champions? GENDER We always gender balance our weekenders, but cannot control who opts to do what classes or dance in particular dance zones, so CONTROLLED BOOKING SYSTEM there may appear to be an imbalance at certain times, but at least PRIVATE LESSONS PUB QUIZZES you understand better the dynamic of this weekend. -

OUR EXPERIENCE with DANCING CLASSROOMS by Julie Jacobson Kendle

OUR EXPERIENCE WITH DANCING CLASSROOMS By Julie Jacobson Kendle Photos by C.J. Hurst Photo subjects are Olivia and her partner Patric Years ago (pre-marriage, pre-chil- teaching when I was just 12) my so much easier to think about in- dren) I watched the award win- kids are not trained in ballroom stead of difcult. She really likes ning documentary “Mad Hot dance. They’ve enjoyed some kids, and that’s awesome, and Ballroom”. Little did I know that community-ed ballet classes and she respects kids.” someday I would volunteer in they love skiing, swimming, act- that very program with my yet ing, and the arts. They would not As a professional dancer and unborn daughter, both of us en- have been able to show you a teacher, it was fascinating for thusiastic participants. rumba box or tango basic, so this me to observe the method that program was going to be a great is universally used by Dancing Two years ago, Dancing Class- introduction to ballroom dance Classrooms to teach children to rooms came to Minnesota under for my daughter. dance. It is a scripted approach the direction of Andrea Miren- that teaches Merengue, Foxtrot, da and Ember Reichgott Junge, To share this experience with Rumba, Waltz, Tango, Swing and co-presidents of the afliated Olivia, I became an ofcial Class- Polka patterns in a clear-cut order. non-proft Heart of Dance. Re- room Assistant, and every Tues- However, the program is much becca and Bruce Abas, owners day and Thursday morning, I more than about teaching kids to of Four Seasons Dance Studio, helped Linwood Monroe’s Danc- dance. -

Dancers of Tango Argentino Use Imagery for Interaction and Improvisation

Journal of Cognitive Semiotics , IV (1): 76-124. http://www.cognitivesemiotics.com . Michael Kimmel University of Vienna Intersubjectivity at Close Quarters: How Dancers of Tango Argentino Use Imagery for Interaction and Improvisation The article explores the prerequisites of embodied ‘conversations’ in the improvisational pair dance tango argentino . Tango has been characterized as a dialog of two bodies. Using first- and second-person phenomenological methods, I investigate the skills that enable two dancers to move as a super-individual ensemble, to communicate without time lag, and to feel the partner’s intention at every moment. How can two persons – walking in opposite directions and with partly different knowledge – remain in contact throughout, when every moment can be an invention? I analyze these feats through the lens of image schemas such as BALANCE , FORCE , PATH , and UP -DOWN (Johnson 1987). Technique-related discourse – with its use of didactic metaphor – abounds with image-schematic vectors, geometries, and construal operations like profiling. These enable the tango process: from posture, via walking technique and kinetics, to attention and contact skills. Dancers who organize their muscles efficiently – e.g., through core tension – and who respect postural ‘grammar’ – e.g., a good axis – enable embodied dialog by being receptive to their partners and being manoeuvrable. Super-individual imagery that defines ‘good’ states for a couple to stick to, along with relational attention management and kinetic calibration of joint walking, turns the dyad into a single action unit. My further objective is a micro-phenomenological analysis of joint improvisation. This requires a theory to explain dynamic sensing, the combining of repertory knowledge with this, and the managing of both in small increments. -

Argentine Tango: Another Behavioral Addiction?

Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(3), pp. 179–186 (2013) JournalDOI: of10.1556/JBA.2.2013.007 Behavioral Addictions First publishedDOI: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.007 online June 14, 2013 Argentine tango: Another behavioral addiction? REMI TARGHETTA1#, BERTRAND NALPAS1,2*# and PASCAL PERNEY1 1Service d’Addictologie, CHU Caremeau, Nîmes, France 2Inserm U1016, Nîmes, France (Received: December 14, 2012; revision received: February 22, 2013; second revision received: April 8, 2013; accepted: April 9, 2013) Background: Behavioral addiction is an emerging concept based on the resemblance between symptoms or feelings provided by drugs and those obtained with various behaviors such as gambling, etc. Following an observational study of a tango dancer exhibiting criteria of dependence on this dance, we performed a survey to assess whether this case was unique or frequently encountered in the tango dancing community. Methods: We designed an online survey based on both the DSM-IV and Goodman’s criteria of dependence; we added questions relative to the positive and negative effects of tango dancing and a self-evaluation of the degree of addiction to tango. The questionnaire was sent via Internet to all the tango dancers subscribing to “ToutTango”, an electronic monthly journal. The prevalence of dependence was analyzed using DSM-IV, Goodman’s criteria and self-rating scores separately. Results: 1,129 tango dancers answered the questionnaire. Dependence rates were 45.1, 6.9 and 35.9%, respectively, according to the DSM-IV, Goodman’s criteria and self-rating scores. Physical symptoms of withdrawal were reported by 20% of the entire sample and one-third described a strong craving for dancing. -

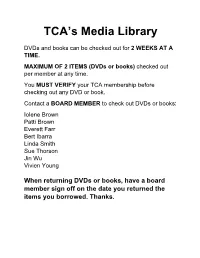

TCA's Media Library

TCA’s Media Library DVDs and books can be checked out for 2 WEEKS AT A TIME. MAXIMUM OF 2 ITEMS (DVDs or books) checked out per member at any time. You MUST VERIFY your TCA membership before checking out any DVD or book. Contact a BOARD MEMBER to check out DVDs or books: Iolene Brown Patti Brown Everett Farr Bert Ibarra Linda Smith Sue Thorson Jin Wu Vivien Young When returning DVDs or books, have a board member sign off on the date you returned the items you borrowed. Thanks. Tango Club of Albuquerque Video Rentals – Complete List V1 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 1 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The first tape covers the basics including the proper embrace and elementary steps. The video quality is high and so is the instruction. The voice over is a bit dramatic and sometimes slightly out of synch with the steps. The tapes are a somewhat expensive for the amount of material covered, but this is a good series for anyone just starting in Tango. V2 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 2 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The second and third videos cover additional steps including complex figures and embellishments.