Dancers of Tango Argentino Use Imagery for Interaction and Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond

A Delicate Balance Negotiating Isolation and Globalization in the Burmese Performing Arts Catherine Diamond If you walk on and on, you get to your destination. If you question much, you get your information. If you do not sleep and idle, you preserve your life! (Maung Htin Aung 1959:87) So go the three lines of wisdom offered to the lazy student Maung Pauk Khaing in the well- known eponymous folk tale. A group of impoverished village youngsters, led by their teacher Daw Khin Thida, adapted the tale in 2007 in their first attempt to perform a play. From a well-to-do family that does not understand her philanthropic impulses, Khin Thida, an English teacher by profession, works at her free school in Insein, a suburb of Yangon (Rangoon) infamous for its prison. The shy students practiced first in Burmese for their village audience, and then in English for some foreign donors who were coming to visit the school. Khin Thida has also bought land in Bagan (Pagan) and is building a culture center there, hoping to attract the street children who currently pander to tourists at the site’s immense network of temples. TDR: The Drama Review 53:1 (T201) Spring 2009. ©2009 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 93 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram.2009.53.1.93 by guest on 02 October 2021 I first met Khin Thida in 2005 at NICA (Networking and Initiatives for Culture and the Arts), an independent nonprofit arts center founded in 2003 and run by Singaporean/Malaysian artists Jay Koh and Chu Yuan. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Dance, Senses, Urban Contexts

DANCE, SENSES, URBAN CONTEXTS Dance and the Senses · Dancing and Dance Cultures in Urban Contexts 29th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology July 9–16, 2016 Retzhof Castle, Styria, Austria Editor Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors Liz Mellish Andriy Nahachewsky Kurt Schatz Doris Schweinzer ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Performing Arts Graz Graz, Austria 2017 Symposium 2016 July 9–16 International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Ethnochoreology The 29th Symposium was organized by the ICTM Study Group on Ethnochoreology, and hosted by the Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of Music and Perfoming Arts Graz in cooperation with the Styrian Government, Sections 'Wissenschaft und Forschung' and 'Volkskultur' Program Committee: Mohd Anis Md Nor (Chair), Yolanda van Ede, Gediminas Karoblis, Rebeka Kunej and Mats Melin Local Arrangements Committee: Kendra Stepputat (Chair), Christopher Dick, Mattia Scassellati, Kurt Schatz, Florian Wimmer Editor: Kendra Stepputat Copy-editors: Liz Mellish, Andriy Nahachewsky, Kurt Schatz, Doris Schweinzer Cover design: Christopher Dick Cover Photographs: Helena Saarikoski (front), Selena Rakočević (back) © Shaker Verlag 2017 Alle Rechte, auch das des auszugsweisen Nachdruckes der auszugsweisen oder vollständigen Wiedergabe der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlage und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-8440-5337-7 ISSN 0945-0912 Shaker Verlag GmbH · Kaiserstraße 100 · D-52134 Herzogenrath Telefon: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 0 · Telefax: 0049 24 07 / 95 96 9 Internet: www.shaker.de · eMail: [email protected] Christopher S. DICK DIGITAL MOVEMENT: AN OVERVIEW OF COMPUTER-AIDED ANALYSIS OF HUMAN MOTION From the overall form of the music to the smallest rhythmical facet, each aspect defines how dancers realize the sound and movements. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

Social Tango

Social Tango Richard Powers Argentine tango has been popular around the world for over a century. Therefore it has evolved into several different forms. This doc describes social tango, sometimes called American tango. The world first saw tango when Argentine dancers brought it to Paris around 1910. It quickly became the biggest news in Paris—the 1912 Tangomania. Dancers around the world fell in love with tango and added it to their growing repertoire of social dances. When we compare 1912 European and North American tango descriptions to Argentine tango manuals from the same time, we see that the northern hemisphere dancers mostly got it right, dancing the same steps in the same style as the Argentines. Then as time went on, social dancers had no reason to change it. It wasn't broken, so why fix it? Today's social tango is essentially the continuation of the original 1912 Argentine tango. There have been a few evolutionary changes over time, like which foot to start on, but they're relatively minor compared to the greater changes that have been made to the other two forms of tango. Ironically, some people call this American Style tango. This is to differentiate it from International Style (British) tango, but it's nevertheless odd to call the nearly-unchanged original Argentine tango "American," unless one means South American. Many dancers in the world know social tango so this is worth learning. That doesn't mean it's "better" than the other forms of tango—that depends on one's personal preference. But social tango is a very useful kind of tango for dancing with friends at parties, weddings and ocean cruises. -

3671 Argentine Tango (Gold Dance Test)

3671 ARGENTINE TANGO (GOLD DANCE TEST) Music - Tango 4/4 Tempo - 24 measures of 4 beats per minute - 96 beats per minute Pattern - Set Duration - The time required to skate 2 sequences is 1:10 min. The Argentine Tango should be skated with strong edges and considerable “élan”. Good flow and fast travel over the ice are essential and must be achieved without obvious effort or pushing. The dance begins with partners in open hold for steps 1 to 10. The initial progressive, chassé and progressive sequences of steps 1 to 6 bring the partners on step 7 to a bold LFO edge facing down the ice surface. On step 8 both partners skate a right forward outside cross in front on count 1 held for one beat. On step 9, the couple crosses behind on count 2, with a change of edge on count 3 as their free legs are drawn past the skating legs and held for count 4 to be in position to start the next step, crossed behind for count 1. On step 10 the man turns a counter while the woman executes another cross behind then change of edge. This results in the partners being in closed hold as the woman directs her edge behind the man as he turns his counter. Step 11 is strongly curved towards the side of the ice surface. At the end of this step the woman momentarily steps onto the RFI on the “and” between counts 4 and 1 before skating step 12 that is first directed toward the side barrier. -

Issue 1 : ( Non ) Conformity ( Vol

N O . 1 V O L U M E 1 / N O V E M B E R 2 Lingua 0 2 0 NI S S U E 1a : ( N OtN ) CoO N F OlR MiI TnY ( V OaL . 1 ) US AND THEM SERBIA: WANNA LIVE LIKE ON DANCE: A RETURN OF THE COMMON PEOPLE: NOTES ON NON-ALIGNMENT ON THE APOLITICISM POLICY? MUSEUMIFICATION OF SPACE Uladzimir Niakliaeŭ Antoine Granier Liza Deléon Simon Berger Lingua Natolina E D I T O R I A L It is Lingua Natolina’s belief that the accomplishment of cross-cultural meaning is both a personal and collective adventure beyond the borders set by language and conventional forms of expression. In this sense, rather than a definitive and coherent outlet, our hybrid and multilingual journal is an experience in European intellectual community. The College of Europe's students hail from over 50 countries. By bringing together the talented students of the College of Europe Mario-Soares Promotion (2020-2021), and key voices in the pan-European cultural discourse, we intend to lift up a true Babel-like cacophony that has the potential to spur intercultural and multilingual dialogue further. In this first volume of our issue on (non)conformity, readers will find a collection of academic and creative essays, as well as stories and art that bears witness to the rich cultural tapestry of Europe. This volume includes original texts in Belarusian, German, Italian, French, and English from students and key artists, writers, academics, and political figures. This seminal motivation to enact a shift away from conventional modes of expression led to the choice of the theme of (non)conformity through which form could match content in our first issue. -

Samba, Rumba, Cha-Cha, Salsa, Merengue, Cumbia, Flamenco, Tango, Bolero

SAMBA, RUMBA, CHA-CHA, SALSA, MERENGUE, CUMBIA, FLAMENCO, TANGO, BOLERO PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL DAVID GIARDINA Guitarist / Manager 860.568.1172 [email protected] www.gozaband.com ABOUT GOZA We are pleased to present to you GOZA - an engaging Latin/Latin Jazz musical ensemble comprised of Connecticut’s most seasoned and versatile musicians. GOZA (Spanish for Joy) performs exciting music and dance rhythms from Latin America, Brazil and Spain with guitar, violin, horns, Latin percussion and beautiful, romantic vocals. Goza rhythms include: samba, rumba cha-cha, salsa, cumbia, flamenco, tango, and bolero and num- bers by Jobim, Tito Puente, Gipsy Kings, Buena Vista, Rollins and Dizzy. We also have many originals and arrangements of Beatles, Santana, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison, Guns & Roses and Rodrigo y Gabriela. Click here for repertoire. Goza has performed multiple times at the Mohegan Sun Wolfden, Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, River Camelot Cruises, festivals, colleges, libraries and clubs throughout New England. They are listed with many top agencies including James Daniels, Soloman, East West, Landerman, Pyramid, Cutting Edge and have played hundreds of weddings and similar functions. Regular performances in the Hartford area include venues such as: Casona, Chango Rosa, La Tavola Ristorante, Arthur Murray Dance Studio and Elizabeth Park. For more information about GOZA and for our performance schedule, please visit our website at www.gozaband.com or call David Giardina at 860.568-1172. We look forward -

Ballet Terms Definition

Fundamentals of Ballet, Dance 10AB, Professor Sheree King BALLET TERMS DEFINITION A la seconde One of eight directions of the body, in which the foot is placed in second position and the arms are outstretched to second position. (ah la suh-GAWND) A Terre Literally the Earth. The leg is in contact with the floor. Arabesque One of the basic poses in ballet. It is a position of the body, in profile, supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind and at right angles to it, and the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line along the body. Attitude A pose on one leg with the other lifted in back, the knee bent at an angle of ninety degrees and well turned out so that the knee is higher than the foot. The arm on the side of the raised leg is held over the held in a curved position while the other arm is extended to the side (ah-tee-TEWD) Adagio A French word meaning at ease or leisure. In dancing, its main meaning is series of exercises following the center practice, consisting of a succession of slow and graceful movements. (ah-DAHZ-EO) Allegro Fast or quick. Center floor allegro variations incorporate small and large jumps. Allonge´ Extended, outstretched. As for example, in arabesque allongé. Assemble´ Assembled or joined together. A step in which the working foot slides well along the ground before being swept into the air. As the foot goes into the air the dancer pushes off the floor with the supporting leg, extending the toes. -

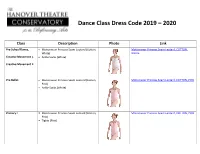

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020 Class Description Photo Link Pre-School Dance, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, White) WHITE Creative Movement I, Ankle Socks (White) Creative Movement II Pre-Ballet Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) Ankle Socks (White) Primary I . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) . Tights (Pink) Primary II . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, Light Blue) LIGHT BLUE . Tights (Pink) Primary III . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Royal Blue) ROYAL BLUE . Tights (Pink) Teen Ballet & . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Hunter Green) HUNTER GREEN Adult Ballet II . Tights (Pink) Level A . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Fuchsia) FUCHSIA . Tights (Pink) Level B . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Bright Red) BRIGHT RED . Tights (Pink) Level C . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Maroon) MAROON . Tights (Pink) Level D, . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Black) BLACK Boys & Girls Club, . Tights (Pink) Adult Ballet Youth Ballet Company . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, (Apprentice) Butter) BUTTER . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style white leotard (Junior) . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style black leotard (Senior) . On the 2nd Saturday of each month any color leotard is allowed. Tights (Pink) Boys Ballet . Motionwear Cap Sleeve Fitted T-Shirt . Motionwear Mens Cap Sleeve Fitted t-shirt, (Silkskyn, White) SILKSKYN, WHITE . -

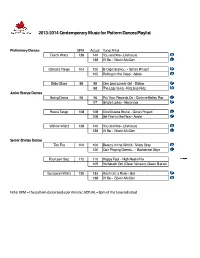

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist Preliminary Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Dut ch Walt z 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Can ast a Tan go 104 100 El Capitalismo... - Gotan Project 105 Rolling in the Deep - Adele Baby Bl ues 88 88 One Less Lonely Girl - Bieber 88 The Lazy Song - Kidz bop Kidz Ju n i o r Br o n z e D a n ce s Sw i n g Da n c e 96 96 Put Your Records On - Corinne Bailey Rae 97 Single Ladies - Beyoncee Fi est a Tango 108 108 Una Musica Brutal - Gotan Project 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele Willow Waltz 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Se ni or Br onze Da nce s Ten Fox 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Fo ur t een St ep 112 110 Happy Feet - High Heels Mix 109 Hollaback Girl (Clean Version)-Gwen Stefani Eu r o p ean Wal t z 135 133 Kiss from a Rose - Seal 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Note: BPM = the pattern dance beats per minute; ACTUAL = bpm of the tune indicated _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist pg2 Junior Silver Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Keat s Foxt r ot 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Ro ck er Fo xt r o t 104 104 Black Horse & the Cherry Tree - KT Tunstall 104 Never See Your Face Again- Maroon 5 Harris Tango 108 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele 111 Gotan Project - Queremos Paz American Walt z 198 193 Fal l i n - Al i ci a Keys -

Amateur Mul Dance & Scholarship Entry Form

Form Leader: Age: DOB: mm/dd/yy: NDCA#: Studio: F Follower: Age: Teacher: Amateur Mul� Dance & Scholarship Entry Form DOB: mm/dd/yy: NDCA#: Phone: Adult contact name: Email: Amateur Rhythm Amateur Int'l Ballroom $ Per Category Dances Couple Category Dances $ Per Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Sun Day - Session 10 40 Amateur Under 21 - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero Amateur Under 21 - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Wed Eve - Session 3 Fri Day - Session 6 Pre-Novice - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba 40 Pre-Novice - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango 40 Novice - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing 40 Pre-Novice - Int'l Ballroom Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Pre-Championship - American Rhythm Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero 50 Novice - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Senior Open - American Rhythm (35+) Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero 50 Pre-Championship - Int'l Ballroom Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, Quickstep 40 Open Am - Am Rhythm Scholarship Cha Cha, Rumba, Swing, Bolero, Mambo 55 Senior Open - Int'l Ballroom (35+) Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 50 $ Total Amateur Rhythm Dance Entries: Masters Open - Int'l Ballroom (51+) Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep 50 Fri Eve - Session 7 55 Open Am - Int'l Ballroom Scholarship Waltz, Tango, V. Waltz, Foxtrot, Quickstep Amateur Smooth $ $ Per Total Amateur Int'l Ballroom Dance Entries: Category Dances Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Amateur Under 21 - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, V. Waltz 40 Amateur Int'l La�n Thu Eve - Session 5 Category Dances $ Per Pre-Novice - American Smooth Waltz, Tango 40 Couple Sun Day - Session 10 Novice - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot 40 Amateur Under 21 - Int'l La�n Cha Cha, Samba, Rumba, Paso Doble, Jive 40 Pre-Championship - American Smooth Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, V.