Cal Olson and Photojournalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase One H 20 Getting Started

H 20 GETTING START E D PostScript billede (black logo) Phase One A/S Phase One U.S. Roskildevej 39 24 Woodbine Ave DK-2000 Frederiksberg Northport, New York Denmark 11768 USA Tel +45 36 46 01 11 Tel +1 631-757-0400 Fax +45 36 46 02 22 Fax +1 631-757-2217 Notice The name Phase One is a trademark of Phase One A/S. The names Hasselblad, Mamiya and Rollei are registered trademarks of their respective companies. All specifications are subject to change without notice. Phase One takes no responsibility for any loss or damage sustained while using their products. This manual ©2003, Phase One A/S Denmark. All rights reserved. No part of this manual may be reproduced or copied in any way without prior written permission of Phase One. Printed in Denmark. Part #: 80016001 Table of Contents 1 Contents 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n . .2 2 Special Phase One H 20 features . .3 ISO Settings . .3 Double exposure protection . .3 IR filter on CCD . .4 Large format photography . .4 3 Getting ready for taking pictures . .6 Mounting the viewfinder mask . .6 Mounting the H 20 on a Hsselblad Camera . .7 Cable mounting on Hasselblad . .8 Hasselblad 553 ELX . .9 Hasselblad 555 ELD . .10 Hasselblad 501 CM and 503 CW . .10 Mamiya RZ67 Pro II . .11 Rolleiflex 6008 AF/Integrale . .13 4 Maintenance . .17 Cleaning the IR filter . .17 5 Technical data . .18 1 H 20 Getting Started 1 Introduction The Phase One H 20 single shot camera back, is designed for high-end advertising studios with a need for productivity, flexibility and the absolute best in image quality. -

User Manual Hasselblad CF Digital Camera Back Range C O N T E N T S

User Manual Hasselblad CF Digital Camera Back Range C O N T E N T S Introduction 3 5 MENU—ISO, White balance, Media, Browse 31 1 General overview 6 Menu system overview 31 Parts, components and control panel 8 Navigating the menu system 31 Initial setup 10 Language choice 33 Shooting and storage modes 11 ISO 33 White balance 34 2 Initial General Settings 14 Media 34 Overview of menu structure 15 Browse 35 Setting the menu language 17 6 MENU—Storage 36 Delete 37 3 Storage overview – Format 42 working with media and batches 18 Copy 42 Batc hes 18 Batch 43 Navigating media and batches 18 Default Approval Level 44 Creating new batches 20 Using Instant Approval Architecture 21 7 MENU—Settings 45 Reading and changing approval status 22 User Interface 46 Browsing by approval status 22 Camera 48 Deleting by approval status 23 Capture sequence 50 Connectivity 51 4 Overview of viewing, deleting Setting exposure time/sequence 54 and copying images 24 Miscellaneous 56 Basic image browsing 24 About 57 Choosing the current batch 24 Default 58 Browsing by approval status 24 Zooming in and out 24 8 Multishot 59 Zooming in for more detail 25 Thumbnail views 25 General 59 Preview modes 26 Histogram 27 9 Flash/Strobe 60 Underexposure 27 General 60 Even exposure 27 TTL 60 Overexposure 27 Full-details 27 10 Cleaning 61 Battery saver mode 28 Full-screen mode 28 11 Equipment care, service, Overexposure indicator 28 technical spec. 63 Deleting images 29 General 63 Transferring images 29 Technical specifications 64 Inset photo on cover: © Francis Hills/www.figjamstudios.com.Not all the images in this manual were taken with a Hasselblad CF. -

Possibilities of Processing Archival Photogrammetric Images Captured by Rollei 6006 Metric Camera Using Current Method

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2, 2018 ISPRS TC II Mid-term Symposium “Towards Photogrammetry 2020”, 4–7 June 2018, Riva del Garda, Italy POSSIBILITIES OF PROCESSING ARCHIVAL PHOTOGRAMMETRIC IMAGES CAPTURED BY ROLLEI 6006 METRIC CAMERA USING CURRENT METHOD A. Dlesk 1,*, P. Raeva 1, K. Vach 2 1 Department of Geomatics, CTU in Prague - [email protected] 2 EuroGV s.r.o. - [email protected] Commission II, WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Rollei 6006 metric, Photo negatives, Structure from motion, Archival data, Close range photogrammetry ABSTRACT: Processing of analog photogrammetric negatives using current methods brings new challenges and possibilities, for example, creation of a 3D model from archival images which enables the comparison of historical state and current state of cultural heritage objects. The main purpose of this paper is to present possibilities of processing archival analog images captured by photogrammetric camera Rollei 6006 metric. In 1994, the Czech company EuroGV s.r.o. carried out photogrammetric measurements of former limestone quarry the Great America located in the Central Bohemian Region in the Czech Republic. All the negatives of photogrammetric images, complete documentation, coordinates of geodetically measured ground control points, calibration reports and external orientation of images calculated in the Combined Adjustment Program are preserved and were available for the current processing. Negatives of images were scanned and processed using structure from motion method (SfM). The result of the research is a statement of what accuracy is possible to expect from the proposed methodology using Rollei metric images originally obtained for terrestrial intersection photogrammetry while adhering to the proposed methodology. -

First Experiences with the New Digital Camera Rollei D7 Metric

FIRST EXPERIENCES WITH THE NEW DIGITAL CAMERA ROLLEI D7 METRIC Prof. Dr.-Ing. Guenter Pomaska FH Bielefeld, University of Applied Sciences Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Artilleriestr. 9 D-32427 Minden eMail: [email protected] CIPA Working Group II / V Keywords: Digital camera,CCD-sensor, digital photography Abstract: Numerous digital cameras with megapixel resolution are available today. The requirements to a metric camera are a fixed focus and focal length, known lens distortion and known position of the principle point relative to the sensor elements. Application software has to provide correction of those deformations. Image quality can be very important when using correlation procedures. Focusing on new presentation technologies like texture mapping, panoramic images, digital stereo pictures and internet presentation is a legitimation for those kind of cameras. Rollei Fototechnic has introduced a new digital camera with SLR technique, fixed focus and focal length and a sensor with 1.4 million pixels. Images are stored in a raw data format and can be corrected under respect of the factory calibration parameters. Details of camera construction and handling are discussed. Some applications best suited for digital camera recording are presented. 1. OPTICAL AND MECHANICAL COMPONENTS OF THE CAMERA The camera is designed in separate groups all assembled in a sturdy metal body. Lens, mirror, viewfinder and sensor are connected to the front plate of the body, while monitor, storage media, electronic elements and interfaces are fixed at the back of the camera housing. Figure 1 displays a principle construction drawing, here with a zoom lens. The SLR single lens reflection principle displays the image in the viewfinder exactly as it will be on the CCD- sensor. -

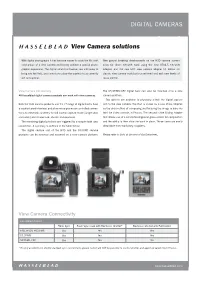

View Camera Solutions

DIGITAL CAMERAS View Camera solutions With digital photography it has become easier to work the tilt/shift New ground breaking developments on the H3D camera system mechanism of a view camera and hereby achieve a special photo- allow for direct tilt/shift work using the new HTS1.5 tilt/shift graphic expression. The digital solutions however, are still heavy to adapter, and the new HVC view camera adapter kit allows for bring into the field, and controls to place the wanted focus correctly classic view camera work both un-tethered and with new levels of are not optimal. focus control. View Camera Connectivity The CF/CF-MS/CFV digital back can also be mounted onto a view All Hasselblad digital camera products can work with view cameras. camera platform. Two options are available to physically attach the digital capture Both the H3D camera products and the CF range of digital backs have unit to the view camera. The first is known as a Live Video Adapter, a sophisticated interface, and allow micro-processor controlled connec- as the only method of composing and focusing the image is done via tions to electronic shutters for full control capture mode (single-shot, the Live Video controls in Phocus. The second is the Sliding Adapter multi-shot) and of aperture, shutter and exposure. that allows use of a conventional ground glass screen for composition The remaining digital products are triggered by a simple flash sync and the ability to then slide the back in place. These items are easily connection. A summary is outlined in the table below. -

Rolleifle,X 2.8F IMPROVING on When the Rolleiflex 2.8F Was Created, Astar Was Born

HOW Amateur Photographer's... Ie P 0 06 MUCH o HEY PHOTOGRAPHER I PHOTOGRAPH I COST? AType 1Rolleiflex 2,8F with 80mm Planar and exposure AType 1version of the meter, showing late 1950s, with 75mm 'moderate/heavy use' 1/3.5 Planar and built with 'obvious wear in uncoupled exposure to the body covering' meter. Ihis one is in sold for [432,02 on as-bought condition eBay on 16 July, A and has not yet been dealer in Frankfurt cleaned for display sold anear-mint 2.8F with Planar and meter for [1.261 on 11 July. The 3.5F realises similar prices, with similar differences for condition. Amint example of the last 'wl\'ite face' 3.5F with meter and ERe [ever ready easel sold on eBay for [1,874 on, 16 July. AweU-used but sound 3.5F with ptanar and accessories sold for [436.20 on 14 July A3.5F with f/3.5 Xenotar and needing a the optical quality of the 80mm f/2.8 Carl shutter service [which Zeiss Planar and the ultimate mechanical could be pricey] sold leaf shutter of the time, the Synchro for [171 on 11 July. The classic Type 1of the 1960s, Compur As acreative tool, particularly for These examples show pictures of people, it was unsurpassed, that prices of 2.8F with 80mm f/28 Planar and built-in The companion to the 28F, the Rolleiflex and 3.5F Rolleiflexes 35F, had been launched in 1958 with either vary dramatically with selenium-cell exposure meter an f/35 Zeiss Planar or an f/35 Schneider condition. -

Hasselblad Ixpress CF V1 1.Indd

DIGITAL BACKS HASSELBLAD Ixpress CF 132 / Ixpress CF 528 The Ixpress CF line of digital backs offers 22Mpix digital capture with the Hasselblad open camera inter- face, the i-Adapter, and the option for true colour multi-shot capture. The Ixpress offers new levels of flexibility to the specialist profes- sional photographers enabling them to take full advantage of everything that leading edge digital photogra- phy can offer. Ixpress CF 132 Ixpress CF 528 Large format digital capture Working with multiple cameras — the i-Adapter Today’s photographers demand higher resolution, less noise, and The Ixpress CF interfaces with a simple 4-screw attached plate to improved flexibility, all of which the Ixpress CF addresses. The Ixpress most of the professional SLR and view cameras on the market. You CF suits cameras with an optical format allowing for digital capture can therefore obtain digital capture with your favourite cameras and with sensors more than twice the physical size of today’s 35mm lenses with one digital back. See detailed list of supported cameras sensors. The sensor therefore holds more and larger pixels, which below. secure a high-end image quality in terms of moiré free color rendering without gradation break-ups in even the finest lit surfaces. Direct shooting to Adobe DNG Hasselblad has partnered closely with Adobe to make its new prod- “Instant” user interface ucts fully compatible with Adobe’s raw image format DNG (‘Digital The Ixpress CF is operated with a straightforward user interface with NeGative’), bringing this new technology standard to the professional a series of “instant” one-button-click operations including: instant photographer for the first time. -

Visual Communications Journal

Visual CommunicationsSpring 2017, Volume 53, Number 1 Journal Medium Format Cameras for Digital Photography CHRIS J. LANTZ, Ph.D. Volume 53 Number 1 SPRING 2017 Acknowledgements President – Mike Stinnett Royal Oak High School (Ret.) Editor 21800 Morley Ave. Apt 517 Dan Wilson, Illinois State University Dearborn, MI 48124 (313) 605-5904 Editorial Review Board [email protected] Cynthia Carlton-Thompson, North Carolina A&T State University President-Elect – Malcolm Keif Bob Chung, Rochester Institute of Technology Cal Poly University Christopher Lantz, Western Illinois University Graphic Communications Devang Mehta, North Carolina A&T State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Tom Schildgen, Arizona State University 805-756-2500 Mark Snyder, Millersville University [email protected] James Tenorio, University of Wisconsin–Stout First Vice-President (Publications) Renmei Xu, Ball State University Gabe Grant Cover Design Eastern Illinois University School of Technology Ben Alberti, Western Technical College 600 Lincoln Avenue Instructor, Barbara Fischer Charleston, IL 61920 (217) 581-3372 Page Design, Layout, and Prepress [email protected] Janet Oglesby and Can Le Second Vice-President (Membership) Can Le Printing, Bindery, and Distribution University of Houston Harold Halliday, University of Houston 312 Technology Bldg. University of Houston Printing and Postal Services Houston, TX 77204-4023 (713) 743-4082 About the Journal [email protected] TheVisual Communications Journal serves as the official journal of the Graphic Secretary – Laura Roberts Communications Education Association, and provides a professional Mattoon High School communicative link for educators and industry personnel associated with 2521 Walnut Avenue design, presentation, management, and reproduction of graphic forms of Mattoon, IL 61938 communication. Manuscripts submitted for publication are subject to peer (217) 238-7785 review. -

A History of the Photojournalism Department of the Deseret News 1948 to 1970

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1972 A History of the Photojournalism Department of the Deseret News 1948 to 1970 Richard J. Nye Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Nye, Richard J., "A History of the Photojournalism Department of the Deseret News 1948 to 1970" (1972). Theses and Dissertations. 4988. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A HISTORY OF THE PHOTOJOURNALISM DEPARTMENT OF THE DESERET NEWS 1948 TO 1970 A Thesis Presented to the Department of Communications Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by- Richard J. Nye May, 1972 This thesis, by Richard Jensen Nye, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Communications of Brigham Young University as satisfying the thesis require ment for the degree of Master of Arts. D<*te Raymond Beckham, Committee Chairman^ Owen Rich, Committee Member Edwin 0. Haroldsen, Department Chairman ii A HISTORY OF THE PHOTOJOURNALISM DEPARTMENT OF THE DESERET NEWS 1948 TO 1970 Richard Jensen Nye Department of Communications M.A. Degree, May 1972 ABSTRACT The photojournalism department of the Deseret News is presently one of the most highly organized and productive departments within the newspaper itself. -

MEDIUM FORMAT 100Mm Lens

Section1 MediumFormat Introduction . 10 Bronica 6x4.5 . 11-16 Bronica 6x6 . 17-22 Bronica 6x7 . 23-27 Fuji 6x4.5 . 28 Fuji 6x7 . 29 Fuji 6x8 . 30-32 Fuji 6x9 . 33 Hasselblad 6x6 . 34-54 LRX (Beattie) . 55-56 Mamiya 6x4.5 . 57-64 Mamiya 6x6 . 65-66, 75 Mamiya 6x7 . 67-82 Pentax 6x4.5 . 83-89 Pentax 6x7 . 90-95 Rollei 6x6 . 96-109 Hasselblad INTRODUCTION 6x6cm medium ➧ format camera ➧ Bronica MEDIUM FORMAT 100mm lens As the format of choice among wedding, fashion, and Today, most medium portrait photographers, Medium Format includes all format cameras are cameras which accept 120 or 220 film sizes. The out- “system cameras,” standing attraction of medium format is the superlative with popular image available due to the substantially larger film for- options that mat and increased image size on the negative or trans- include motor parency. Because medium format negatives require less winders, inter- enlargement than smaller 35mm negatives to produce changeable viewfinders the same image size on the print, identical negatives on with or without exposure meters, grips and an array or the same type of 35mm and 120/220 film will produce lenses rivaling 35mm in choice. These include perspective remarkably different prints. The 120/220 format delivers control lenses, tele-extenders and zooms. From the 24mm MEDIUM FORMAT more resolution, finer grain, an expanded grey scale, and full-frame fisheye lens to the 500mm telephoto lens with a visually more pleasing image. Medium format cameras low dispersion glass and floating elements, almost every are available in the following different variations: option is available. -

Digital CAMERAS

DIGITAL CAMERAS The H3DII-31 is an integral part of Hasselblad’s H3DII family, digital camera architecture, Hasselblad is able to offer the full part of the fourth generation of our medium format DSLR camera benefits of professional medium format digital cameras with the system. With its unique large and bright viewfinders, its wide range ease-of-use found in the best 35mm DSLRs. of HC and HCD lenses - which match the best of Hasselblad icon With the H3DII architecture as a base, Hasselblad has devel- lenses from Carl Zeiss - and its wide choice of accessories the oped the ultra high-performing HCD 28mm lens, designed and H3DII-31 is an ideal entry point into high-end digital photography optimized solely for digital image capture. Image quality is lifted for any professional photographer. to a level yet unseen in digital photography, including automatic In addition to the added-value options inherent in the Hasselblad digital correction for chromatic aberration, distortion and vignet- camera system, it is Hasselblad image quality that stands out the ting. Hasselblad’s Natural Color Solution delivers out-of-the-box most. The H3DII-31 has been developed around a new digital image quality only achievable in a true digital camera system. camera engine, which delivers increased lens performance and See for yourself by checking out the image quality at: http:// a new level of image sharpness. By focusing on the integrated www.hasselblad.com/products/hasselblad-star-quality.aspx. The H3DII-31 camera system is made for the professional photo- The H3DII-31 features Kodak’s 31 Mpixel sensor, measuring grapher who demands both flexibility and ease-of-use, with features 33×44mm, enhanced with micro-lenses to boost its basic ISO- rating such as: by one full stop to a maximum of ISO800. -

Installation Guide Full

Copyright © Leaf Imaging Ltd., 20. All rights reserved. This document is also distributed in Adobe Systems Incorporated's PDF (Portable Document Format). You may reproduce the document from the PDF file for internal use. Copies produced from the PDF file must be reproduced in whole. Trademarks Adobe, Acrobat, Adobe Illustrator, Distiller, Photoshop, PostScript, and PageMaker are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Apple, AppleShare, AppleTalk, iMac, ImageWriter, LaserWriter, Mac OS, Power Macintosh, and TrueType are registered trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Macintosh is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S.A. and other countries. FCC Compliance Any Leaf Imaging Ltd. equipment referred to in this document complies with the requirements in part 15 of the FCC Rules for a Class A digital device. Operation of the Leaf Imaging Ltd. equipment in a residential area may cause unacceptable interference to radio and TV reception, requiring the operator to take whatever steps are necessary to correct the interference. Equipment Recycling In the European Union, this symbol indicates that when the last user wishes to discard this product, it must be sent to appropriate facilities for recovery and recycling. This electronic information product complies with Standard SJ/T 11363 - 2006 of the Electronics Industry of the People's Republic of China. Limitation of Liability The product, software or services are being provided on an "as is" and "as available" basis. Except as may be stated specifically in your contract, Leaf Imaging Ltd. expressly disclaims all warranties of any kind, whether express or implied, including, but not limited to, any implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose and non-infringement.