Bilingualism and the Indigenous Supreme Court Candidate 797

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of Canada Judgment in Chevron Corp V Yaiguaje 2015

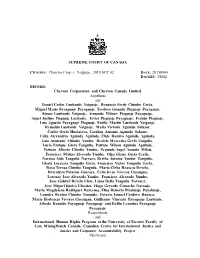

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje, 2015 SCC 42 DATE: 20150904 DOCKET: 35682 BETWEEN: Chevron Corporation and Chevron Canada Limited Appellants and Daniel Carlos Lusitande Yaiguaje, Benancio Fredy Chimbo Grefa, Miguel Mario Payaguaje Payaguaje, Teodoro Gonzalo Piaguaje Payaguaje, Simon Lusitande Yaiguaje, Armando Wilmer Piaguaje Payaguaje, Angel Justino Piaguaje Lucitante, Javier Piaguaje Payaguaje, Fermin Piaguaje, Luis Agustin Payaguaje Piaguaje, Emilio Martin Lusitande Yaiguaje, Reinaldo Lusitande Yaiguaje, Maria Victoria Aguinda Salazar, Carlos Grefa Huatatoca, Catalina Antonia Aguinda Salazar, Lidia Alexandria Aguinda Aguinda, Clide Ramiro Aguinda Aguinda, Luis Armando Chimbo Yumbo, Beatriz Mercedes Grefa Tanguila, Lucio Enrique Grefa Tanguila, Patricio Wilson Aguinda Aguinda, Patricio Alberto Chimbo Yumbo, Segundo Angel Amanta Milan, Francisco Matias Alvarado Yumbo, Olga Gloria Grefa Cerda, Narcisa Aida Tanguila Narvaez, Bertha Antonia Yumbo Tanguila, Gloria Lucrecia Tanguila Grefa, Francisco Victor Tanguila Grefa, Rosa Teresa Chimbo Tanguila, Maria Clelia Reascos Revelo, Heleodoro Pataron Guaraca, Celia Irene Viveros Cusangua, Lorenzo Jose Alvarado Yumbo, Francisco Alvarado Yumbo, Jose Gabriel Revelo Llore, Luisa Delia Tanguila Narvaez, Jose Miguel Ipiales Chicaiza, Hugo Gerardo Camacho Naranjo, Maria Magdalena Rodriguez Barcenes, Elias Roberto Piyahuaje Payahuaje, Lourdes Beatriz Chimbo Tanguila, Octavio Ismael Cordova Huanca, Maria Hortencia Viveros Cusangua, Guillermo Vincente Payaguaje Lusitante, Alfredo Donaldo Payaguaje Payaguaje and Delfin Leonidas Payaguaje Payaguaje Respondents - and - International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, MiningWatch Canada, Canadian Centre for International Justice and Justice and Corporate Accountability Project Interveners CORAM: McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, Cromwell, Karakatsanis, Wagner and Gascon JJ. REASONS FOR JUDGMENT: Gascon J. (McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, (paras. 1 to 96) Cromwell, Karakatsanis and Wagner JJ. -

Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 71 (2015) Article 5 Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Borrows, John. "Aboriginal Title and Private Property." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 71. (2015). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol71/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Aboriginal Title and Private Property John Borrows* Q: What did Indigenous Peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? A: “OURS.”1 I. INTRODUCTION In the ground-breaking case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia2 the Supreme Court of Canada recognized and affirmed Aboriginal title under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.3 It held that the Tsilhqot’in Nation possess constitutionally protected rights to certain lands in central British Columbia.4 In drawing this conclusion the Tsilhqot’in secured a declaration of “ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land”.5 These are wide-ranging rights. -

Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State

We All Belong: Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State by Amar Bhatia A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Amar Bhatia 2018 We All Belong: Indigenous Laws for Making and Maintaining Relations Against the Sovereignty of the State Amar Bhatia Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation proposes re-asserting Indigenous legal authority over immigration in the face of state sovereignty and ongoing colonialism. Chapter One examines the wider complex of Indigenous laws and legal traditions and their relationship to matters of “peopling” and making and maintaining relations with the land and those living on it. Chapter Two shows how the state came to displace the wealth of Indigenous legal relations described in Chapter One. I mainly focus here on the use of the historical treaties and the Indian Act to consolidate Canadian sovereignty at the direct expense of Indigenous laws and self- determination. Conventional notions of state sovereignty inevitably interrupt the revitalization of Indigenous modes of making and maintaining relations through treaties and adoption. Chapter Three brings the initial discussion about Indigenous laws and treaties together with my examination of Canadian sovereignty and its effect on Indigenous jurisdiction over peopling. I review the case of a Treaty One First Nation’s customary adoption of a precarious status migrant and the related attempt to prevent her removal from Canada on this basis. While this attempt was ii unsuccessful, I argue that an alternative approach to treaties informed by Indigenous laws would have recognized the staying power of Indigenous adoption. -

Manitoba, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Québec

Court File No. 38663 and 38781 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal) IN THE MATTER OF THE GREENHOUSE GAS POLLUTION ACT, Bill C-74, Part V AND IN THE MATTER OF A REFERENCE BY THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL TO THE COURT OF APPEAL UNDER THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS ACT, 2012, SS 2012, c C-29.01 BETWEEN: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN APPELLANT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUÉBEC INTERVENERS (Title of Proceeding continued on next page) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP Legal Services Branch, Constitutional Law Section Barristers & Solicitors 1230 - 405 Broadway Suite 2600, 160 Elgin Street Winnipeg MB R3C 3L6 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Michael Conner / Allison Kindle Pejovic D. Lynne Watt Tel: (204) 391-0767/(204) 945-2856 Tel: (613) 786-8695 Fax: (204) 945-0053 Fax: (613) 788-3509 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener Ottawa Agent for the Intervener -and - SASKATCHEWAN POWER CORPORATION AND SASKENERGY INCORPORATED, CANADIAN TAXPAYERS FEDERATION, UNITED CONSERVATIVE ASSOCIATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION OF SASKATCHEWAN INC., INTERNATIONAL EMISSIONS TRADING ASSOCIATION, CANADIAN PUBLIC HEALTH -

Youth Activity Book (PDF)

Supreme Court of Canada Youth Activity Book Photos Philippe Landreville, photographer Library and Archives Canada JU5-24/2016E-PDF 978-0-660-06964-7 Supreme Court of Canada, 2019 Hello! My name is Amicus. Welcome to the Supreme Court of Canada. I will be guiding you through this activity book, which is a fun-filled way for you to learn about the role of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Canadian judicial system. I am very proud to have been chosen to represent the highest court in the country. The owl is a good ambassador for the Supreme Court because it symbolizes wisdom and learning and because it is an animal that lives in Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada stands at the top of the Canadian judicial system and is therefore Canada’s highest court. This means that its decisions are final. The cases heard by the Supreme Court of Canada are those that raise questions of public importance or important questions of law. It is time for you to test your knowledge while learning some very cool facts about Canada’s highest court. 1 Colour the official crest of the Supreme Court of Canada! The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. It consists of the letters S and C encircled by a garland of leaves and was designed by Ernest Cormier, the building’s architect. 2 Let’s play detective: Find the words and use the remaining letters to find a hidden phrase. The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. -

Studying Indigenous Politics in Canada: Assessing Political Science's Understanding of Traditional Aboriginal Governance

Studying Indigenous Politics in Canada: Assessing Political Science's Understanding of Traditional Aboriginal Governance Frances Widdowson, Ezra Voth and Miranda Anderson Department of Policy Studies Mount Royal University Paper Presented at the 84th Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, June 13-15, 2012 In the discipline of political science, the importance of understanding the historical development of political systems is recognized. A historical sequence of events must be constructed and analyzed to determine possible causes and effects when studying politics and government systematically. Introductory political science textbooks lament the minimal historical understanding that exists amongst the student body because it is maintained that those “without a historical perspective are adrift intellectually. They lack the important bearings that make sense of Canada‟s unique history, as well as the development of Western civilization and the rise and 1 fall of other civilizations”. Historical understanding is particularly important in the study of indigenous politics in Canada, where there is a constant attempt to link modern and traditional forms of governance. Understanding aboriginal traditions is essential for achieving aboriginal-non-aboriginal reconciliation, and many political scientists argue that misrepresentations of pre-contact indigenous governance continue to perpetuate colonialism. This makes it important to ask how aboriginal political traditions are being -

Aboriginal Rights in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982

“EXISTING” ABORIGINAL RIGHTS IN SECTION 35 OF THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1982 Richard Ogden* The Supreme Court recognises Métis rights, and Aboriginal rights in the former French colonies, without regard for their common law status. This means that “existing aboriginal rights” in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 need not have been common law rights. The Supreme Court recognises these rights because section 35 constitutionalised the common law doctrine of Aboriginal rights, and not simply individual common law Aboriginal rights. As such, section 35 forms a new intersection between Indigenous and non-Indigenous legal systems in Canada. It is a fresh start – a reconstitutive moment – in the ongoing relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. La Cour suprême reconnaît les droits des Métis, et les droits des peuples autochtones dans les anciennes colonies françaises, sans tenir compte de leur statut en vertu de la common law. Ceci signifie que « les droits existants ancestraux » auxquels fait référence l’article 35 de la Loi constitutionnelle de 1982 n’étaient pas nécessairement des droits de common law. La Cour suprême reconnaît ces droits parce que l’article 35 constitutionnalise la doctrine de common law qui porte sur les droits des peuples autochtones, plutôt que simplement certains droits particuliers des peuples autochtones, tels que reconnus par la common law. Ainsi, cet article 35 constitue une nouvelle intersection entre les systèmes juridiques indigène et non indigène au Canada. Ceci représente un départ à neuf, un moment de reconstitution de la relation qui dure maintenant depuis longtemps entre les peuples indigènes et non indigènes. * Senior Advisor, First Nation and Métis Policy and Partnerships Office, Ontario Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure; currently completing a Ph.D. -

SEVEN GIFTS: REVITALIZING LIVING LAWS THROUGH INDIGENOUS LEGAL PRACTICE* by John Borrows†

SEVEN GIFTS: REVITALIZING LIVING LAWS THROUGH INDIGENOUS LEGAL PRACTICE* by John Borrows† CONTENTS Maajitaadaa (An Introduction) 3 Dibaajimowin (A Story) 4 Niizhwaaswi Miigiwewinan (Seven Gifts) 7 I Nitam-Miigiwewin: Gii’igoshimo (Gift One: Vision) 8 II Niizho-Miigiwewin: Gikinoo’amaage Akiing (Gift Two: Land) 9 III Niso-Miigiwewin: Anishinaabemowin (Gift Three: Language) 9 IV Niiyo-Miigiwewin: Dibaakonigewigamig (Gift Four: Tribal Courts) 10 V Naano-Miigiwewin: Anishinaabe Izhitwaawinan (Gift Five: Customs) 11 VI Ningodwaaso-Miigiwewin: Chi-Inaakonigewinan (Gift Six: Constitutions) 12 VII Niizhwaaso-Miigewewin: Anishinaabe Inaakonigewigamig (Gift Seven: Indigenous Legal Education) 13 Boozhoo nindinawemaaganidoog. Nigig indoodem. Kegedonce nindizhinikaaz. Neyaashiinigmiing indoonjibaa. Niminwendam ayaawaan omaa noongom. Miigwech bi-ezhaayeg noongom. Niwii-dazhindaan chi-inaakonigewin. Anishinaabe izhitwaawinan gaye. I am very grateful for the opportunity to be with you today. I am grateful to be amongst friends. I am thankful to have so many supportive colleagues with us and to know that I am amongst my Elders. Justice Harry LaForme taught me at Osgoode Hall Law School when I was a doctoral student there in the early ‘90s. I am also very grateful for the introductions we received from the Elders, the Chief, and representatives of the Métis Nation. I am thankful we live in a beautiful world. Standing in this room this morning, looking out over the water and seeing Nanaboozhoo, the Sleeping Giant, is a reminder of the power of this place. It was also great to be in the Fort William First Nation’s sugar bush yesterday, nestled between those two escarpments, as the light snow fell on us. It was a reminder of the beauty of the stories that can swirl around us this time of year. -

Towards Implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action in Law Schools: a Settler Harm Reduction Ap

TOWARDS IMPLEMENTING THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION’S CALLS TO ACTION IN LAW SCHOOLS: A SETTLER HARM REDUCTION APPROACH TO RACIAL STEREOTYPING AND PREJUDICE AGAINST INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND INDIGENOUS LEGAL ORDERS IN CANADIAN LEGAL EDUCATION SCOTT J. FRANKS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LAWS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LAW OSGOODE HALL LAW SCHOOL YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2020 © Scott J. Franks, 2020 Abstract Many Canadian law schools are in the process of implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Actions #28 and #50. Promising initiatives include mandatory courses, Indigenous cultural competency, and Indigenous law intensives. However, processes of social categorization and racialization subordinate Indigenous peoples and their legal orders in Canadian legal education. These processes present a barrier to the implementation of the Calls. To ethically and respectfully implement these Calls, faculty and administration must reduce racial stereotyping and prejudice against Indigenous peoples and Indigenous legal orders in legal education. I propose that social psychology on racial prejudice and stereotyping may offer non- Indigenous faculty and administration a familiar framework to reduce the harm caused by settler beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors to Indigenous students, professors, and staff, and to Indigenous legal orders. Although social psychology may offer a starting point for settler harm reduction, its application must remain critically oriented towards decolonization. ii Acknowledgments I have a lot of people to acknowledge. This thesis is very much a statement of who I am right now and how that sense of self has been shaped by others. -

Indigenous Law: Issues, Individuals, Institutions And

Fourword: Issues, Individuals, Institutions and Ideas JOHN BORROWS∗ There is a story about a young man who had a dream. In this dream he saw people scrambling up and down the rugged faces of four hills. When he looked closer he noticed each hill seemed to have different groups of people trying to scale its heights.1 He was perplexed. The first hill, to the east, was covered with very small people. Many were weeping and crying; some were covered in blood or lay lifeless at the base. The foot of the hill where they were piled was shrouded in darkness. The shadows and twisted heap made it hard to see how many were gathered there in death, or life. A bit higher, other tiny bodies could be seen crawling over rocks and spring scrub, determinedly edging their way higher over rough terrain. Knees were scraped, hands were red, but their upward progress was noticeable. At other points it was possible to see some totter forward on wobbly legs, through halting steps and tender help from a few around them. Small bits of tobacco would change hands in thanks. Some were laughing and playing, joyfully climbing to their destination. They seemed to be enjoying the challenge that stood before them. They learned from their mistakes, and carefully watched those around them to see how to go on. Yet, every so often one would trip, or lose their hold on the hill, and tumble and scrape to the bottom. A few had reached the top, and stood in the bright yellow glow of the morning sun. -

Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library

fintFenvir Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library 2009-2019 B O R A L A S K I N L A W L IBRARY , U NIVERSITY OF T O R O N T O F A C U L T Y O F L A W 21 things you may not know about the Indian Act / Bob Joseph KE7709.2 .J67 2018. Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal law / Thomas Isaac. KE7709 .I823 2016 More Information The... annotated Indian Act and aboriginal constitutional provisions. KE7704.5 .A66 Most Recent in Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal autonomy and development in northern Quebec and Labrador / Colin H. Scott, [editor]. E78 .C2 A24 2001 More Information Aboriginal business : alliances in a remote Australian town / Kimberly Christen. GN667 .N6 C47 2009 More Information Aboriginal Canada revisited / Kerstin Knopf, editor. E78 .C2 A2422 2008 More Information Aboriginal child welfare, self-government and the rights of indigenous children : protecting the vulnerable under international law / by Sonia Harris-Short. K3248 .C55 H37 2012 More Information Aboriginal conditions : research as a foundation for public policy / edited by Jerry P. White, Paul S. Maxim, and Dan Beavon. E78 .C2 A2425 2003 More Information Aboriginal customary law : a source of common law title to land / Ulla Secher. KU659 .S43 2014 More Information Aboriginal education : current crisis and future alternatives / edited by Jerry P. White ... [et al.]. E96.2 .A24 2009 More Information Aboriginal education : fulfilling the promise / edited by Marlene Brant Castellano, Lynne Davis, and Louise Lahache. E96.2 .A25 2000 More Information Aboriginal health : a constitutional rights analysis / Yvonne Boyer. -

Court File Number: 37878 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA (ON APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL of MANITOBA) B E T W E E N: NORTHERN

Court File Number: 37878 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF MANITOBA) B E T W E E N: NORTHERN REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY Appellant (Respondent) - and - LINDA HORROCKS and MANITOBA HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Respondents (Appellants) - and - ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA COUNCIL OF ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNALS, CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF COUNSEL TO EMPLOYERS, CANADIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION, DON VALLEY COMMUNITY LEGAL SERVICES, and THE EMPOWERMENT COUNCIL Interveners FACTUM OF THE RESPONDENT, LINDA HORROCKS (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) Paul Champ / Bijon Roy Champ & Associates Equity Chambers 43 Florence Street Ottawa, ON K2P 0W6 T: 613-237-4740 F: 613-232-2680 E: [email protected] [email protected] Solicitors for the Respondent TO: The Registrar Supreme Court of Canada 301 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0J1 AND TO: Pitblado LLP Supreme Advocacy LLP 2500-360 Main Street 100-340 Gilmour Street Winnipeg, MB R3C 4H6 Ottawa, ON K2P 0R3 Per: William S. Gardner, QC Per: Marie-France Major Robert A. Watchman Todd C. Andres T: 204-956-0560 T: 613-695-8855 F: 204-957-0227 F: 613-695-8580 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Solicitors for the Appellant Agent for the Appellant Manitoba Human Rights Commission Gowling WLG 700-175 Hargrave Street 2600-160 Elgin Street Winnipeg, MB R3C 3R8 Ottawa, ON K1P 1C3 Per: Sandra Gaballa Per: D. Lynne Watt Heather Unger T: 204-945-6814 T: 613-786-8695 F: 204-945-1292 F: 613-788-3509 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] [email protected] MLT Aikins LLP 30-360 Main Street Winnipeg, MB R3C 4G1 Per: Thor J.