Amanda Shanor, the New Lochner, 2016 Wisc. L. Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wages of Crying Wolf: a Comment on Roe V. Wade*

The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade* John Hart Ely** The interests of the mother and the fetus are opposed. On which side should the State throw its weight? The issue is volatile; and it is resolved by the moral code which an individual has.' In Roe v. Wade 2 decided January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court- Justice Blackmun speaking for everyone but Justices White and Rehn- quist3-held unconstitutional Texas's (and virtually every other state's4) criminal abortion statute. The broad outlines of its argument are not difficult to make out: 1. The right to privacy, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, is protected by the Due Process Clause of the Four- teenth Amendment.r 2. This right "is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy."4 3. This right to an abortion is "fundamental" and can therefore be regulated only on the basis of a "compelling" state interest." 4. The state does have two "important and legitimate" interests here,8 the first in protecting maternal health, the second in protect- ing the life (or potential life9) of the fetus. 10 But neither can be counted "compelling" throughout the entire pregnancy: Each ma- tures with the unborn child. These interests are separate and distinct. Each grows in substan- * Copyright 0 1973 by John Hart Ely. Professor of Law, Yale Law School. 1. United States v. Vuitch, 402 U.S. 62, 80 (1971) (Douglas, J., dissenting in part). 2. 93 S. Ct. 705 (1973). 3. Were the dissents adequate, this comment would be unnecessary. -

The Pentagon Papers Case and the Wikileaks Controversy: National Security and the First Amendment

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2011 The Pentagon Papers Case and the Wikileaks Controversy: National Security and the First Amendment Jerome A. Barron George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 1 Wake Forest J. L. & Pol'y 49 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V._JB_FINAL READ_NT'L SEC. & FA (DO NOT DELETE) 4/18/2011 11:10 AM THE PENTAGON PAPERS CASE AND THE WIKILEAKS CONTROVERSY: NATIONAL SECURITY AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT JEROME A. BARRON † INTRODUCTION n this Essay, I will focus on two clashes between national security I and the First Amendment—the first is the Pentagon Papers case, the second is the WikiLeaks controversy.1 I shall first discuss the Pentagon Papers case. The Pentagon Papers case began with Daniel Ellsberg,2 a former Vietnam War supporter who became disillusioned with the war. Ellsberg first worked for the Rand Corporation, which has strong associations with the Defense Department, and in 1964, he worked in the Pentagon under then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.3 He then served as a civilian government employee for the U.S. State Department in Vietnam4 before returning to the United † Harold H. Greene Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School (1998–present); Dean, The George Washington University Law School (1979– 1988); B.A., Tufts University; J.D., Yale Law School; LL.M., The George Washington University. -

Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 1 Article 3 2016 Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit Floyd Abrams Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Floyd Abrams, Free Speech and Civil Liberties in the Second Circuit, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 11 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE SPEECH AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN THE SECOND CIRCUIT Floyd Abrams* INTRODUCTION Much of the development of First Amendment law in the United States has occurred as a result of American courts rejecting well-established principles of English law. The U.S. Supreme Court has frequently rejected English law, permitting far more public criticism of the judiciary than would be countenanced in England, rejecting English libel law as being insufficiently protective of freedom of expression1 and holding that even hateful speech directed at minorities receives the highest level of constitutional protection.2 The Second Circuit has played a major role in the movement away from the strictures of the law as it existed in the mother country. In some areas, dealing with the clash between claims of national security and freedom of expression, the Second Circuit predated the Supreme Court’s protective First Amendment rulings. -

Wikileaks, the First Amendment and the Press by Jonathan Peters1

WikiLeaks, the First Amendment and the Press By Jonathan Peters1 Using a high-security online drop box and a well-insulated website, WikiLeaks has published 75,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Afghanistan,2 nearly 400,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Iraq,3 and more than 2,000 U.S. diplomatic cables.4 In doing so, it has collaborated with some of the most powerful newspapers in the world,5 and it has rankled some of the most powerful people in the world.6 President Barack Obama said in July 2010, right after the release of the Afghanistan documents, that he was “concerned about the disclosure of sensitive information from the battlefield.”7 His concern spread quickly through the echelons of power, as WikiLeaks continued in the fall to release caches of classified U.S. documents. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton condemned the slow drip of diplomatic cables, saying it was “not just an attack on America's foreign policy interests, it [was] an attack on the 1 Jonathan Peters is a lawyer and the Frank Martin Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he is working on his Ph.D. and specializing in the First Amendment. He has written on legal issues for a variety of newspapers and magazines, and now he writes regularly for PBS MediaShift about new media and the law. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Noam N. Levey and Jennifer Martinez, A whistle-blower with global resonance; WikiLeaks publishes documents from around the world in its quest for transparency, L.A. -

Back to the Future (Reviewing David Bernstein, Rehabilitating Lochner: Defending Individual Rights Against Progressive Reform (2011)) William D

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Spring 2012 Back to the Future (reviewing David Bernstein, Rehabilitating Lochner: Defending Individual Rights Against Progressive Reform (2011)) William D. Araiza Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 28 Const. Comment. 111 (2012-2013) This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. Book Reviews BACK TO THE FUTURE REHABILITATING LOCHNER: DEFENDING INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS AGAINST PROGRESSIVE REFORM. By David Bernstein.' Chicago, University of Chicago Press. 2011. Pp. viii, 194. $45.00 (Cloth). William D. Araiza2 "If you think Roe' is right, why do you think Lochner4 is wrong?" Constitutional law professors love playing this card with students. We like to think it forces them to confront how their policy preferences influence their legal analysis. And it is a nice trick: Roe v. Wade' responds to many (though not all') students' policy intuitions about the desirability of a broad abortion right, while Lochner v. New York7 is often taught as the paradigmatic anti-canonical case, a dark stain on the Supreme Court in the tradition of Dred Scott v. Sanford' and Plessy v. Ferguson' (the 1. Foundation Professor of Law, George Mason University School of Law. 2. Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School. The reviewer wishes to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Brooklyn Law School Dean's Summer Research Stipend Program. -

The Battle for Public Interest Law: Exploring the Orwellian Nature of the Freedom Based Public Interest Movement

The Battle for Public Interest Law: Exploring the Orwellian Nature of the Freedom Based Public Interest Movement † TIMOTHY L. FODEN I. INTRODUCTION Perform a brief Westlaw or Lexis search on the freedom-based public interest movement and you will come up with very little, if anything at all. Similarly, the typical survey class on public interest law offers no information on the more conservative and libertarian wing of the public interest movement. This lack of readily available information prompts a number of questions. Who are the people behind such organizations? Why is it difficult to find information on their work? What is the movement’s agenda? A brief look at a few of these organizations reveals a number of different goals. Freedom-based public interest groups advocate for traditionally conservative causes. Groups such as the Institute for Justice and the Pacific Legal Foundation have launched litigation campaigns against such institutions as the welfare system and the environmental regulatory regime. Other organizations such as the Alliance Defense Fund litigate for the insertion of religious symbols and practices in public spaces. Running the gamut of conservative causes, the freedom- based public interest legal movement has co-opted the once exclusively liberal term, public interest. The Orwellian name-game behind the self-asserted title “freedom-based public interest law movement”1 (“FBPILM”) is heavily responsible for the newly contested definition of public interest. The reason why there is a lack of ascertainable information on these groups is linked to their seemingly innocuous assumption of the term “public interest.” When thinking of public interest, the average lawyer or law † The author would like to thank Professor Richard Wilson for his encouragement of a peculiar topic that required a somewhat journalistic approach. -

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All Rights Reserved

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All rights reserved. Public Citizen Foundation 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 www.citizen.org ISBN: 978-1-58231-099-2 Doyle Printing, 2016 Printed in the United States of America PUBLIC CITIZEN THE SENTINEL OF DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Preface: The Biggest Get ...................................................................7 Introduction ....................................................................................11 1 Nader’s Raiders for the Lost Democracy....................................... 15 2 Tools for Attack on All Fronts.......................................................29 3 Creating a Healthy Democracy .....................................................43 4 Seeking Justice, Setting Precedents ..............................................61 5 The Race for Auto Safety ..............................................................89 6 Money and Politics: Making Government Accountable ..............113 7 Citizen Safeguards Under Siege: Regulatory Backlash ................155 8 The Phony “Lawsuit Crisis” .........................................................173 9 Saving Your Energy .................................................................... 197 10 Going Global ...............................................................................231 11 The Fifth Branch of Government................................................ 261 Appendix ......................................................................................271 Acknowledgments ........................................................................289 -

Congress Before the Lochner Court

CONGRESS BEFORE THE LOCHNER COURT * KEITH E. WHITTINGTON INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 821 I. THE REGIME PERSPECTIVE ON JUDICIAL REVIEW ............................... 824 II. JUDICIAL REVIEW OF FEDERAL STATUTES , 1890-1919 .......................829 III. INVALIDATING FEDERAL STATUTES .................................................... 835 IV. STRIKING DOWN IMPORTANT REPUBLICAN POLICIES ......................... 838 V. STRIKING DOWN IMPORTANT DEMOCRATIC POLICIES ........................ 845 VI. AND THE REST ..................................................................................... 850 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 855 INTRODUCTION The Lochner Court is remembered as one of the great activist Supreme Courts of U.S. history. During the Lochner era judicial review took on its modern character. Constitutional review of legislation by the Supreme Court became a routine feature of the American political system. Although judicial review itself had, of course, been known for a century, it was only with the Lochner Court that we found the need to develop a particular term to refer to the practice of the judiciary nullifying statutes. Though a variety of terms were floated by commentators of the time, including judicial supremacy, judicial veto, judicial nullification, and judicial paramountcy, “judicial review,” a term associated with the judicial supervision of the new administrative -

9780195181234.Pdf

LOSING THE NEWS Institutions of American Democracy Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Jaroslav Pelikan, Directors Other books in the series Schooling in America: How the Public Schools Meet the Nation’s Changing Needs Patricia Albjerg Graham The Most Democratic Branch: How the Courts Serve America Jeffrey Rosen The Broken Branch: How Congress Is Failing America and How to Get It Back on Track Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein LOSING THE NEWS The Future of the News That Feeds Democracy Alex S. Jones 1 2009 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Alex S. Losing the news : the future of the news that feeds democracy / Alex S. Jones. p. cm. — (Institutions of American democracy) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

New Judicial Federalism

American University Law Review Volume 55 | Issue 2 Article 3 2005 The "New Judicial Federalism" Before its Time: A Comprehensive Review of Economic Substantive Due Process Under State Constitutional Law Since 1940 and the Reasons for its Recent Decline Anthony B. Sanders Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Sanders, Anthony B. “The "New Judicial Federalism" Before its Time: A Comprehensive Review of Economic Substantive Due Process Under State Constitutional Law Since 1940 and the Reasons for its Recent Decline.” American University Law Review 55, no.2 (December 2005): 457-535. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "New Judicial Federalism" Before its Time: A Comprehensive Review of Economic Substantive Due Process Under State Constitutional Law Since 1940 and the Reasons for its Recent Decline Abstract The ominc g of the New Deal may have spelled the end of the Lochner era in the federal courts, but in the state courts Lochner's doctrine of economic substantive due process lives on. Since the New Deal, courts in almost every state have rebuffed the United States Supreme Court and have interpreted their own state constitutions' due process clauses to provide substantive protections to economic liberties. -

New York Law School Magazine, Vol. 33, No. 2 New York Law School

digitalcommons.nyls.edu NYLS Publications New York Law School Alumni Magazine 2014 New York Law School Magazine, Vol. 33, No. 2 New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/alum_mag Recommended Citation New York Law School, "New York Law School Magazine, Vol. 33, No. 2" (2014). New York Law School Alumni Magazine. Book 1. http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/alum_mag/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the NYLS Publications at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in New York Law School Alumni Magazine by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Office of Marketing and Communications 185 West Broadway Magazine • 2014 • VOL. 33, nO. 2 New York, NY 10013-2921 SAVE THE DATE REUNION AND ALUMNI WEEKEND APRIl 23–25, 2015 Mark your calendars, and plan to celebrate New York Law School! The 2015 Reunion and Alumni Weekend is shaping up to be an extraordinary occasion for classes ending in 0 and 5—and for the entire NYLS community. You won’t want to miss it! Reunion Year Class Volunteers Needed Do you want to make sure your class is well represented at Reunion? E-mail [email protected] to join your class committee. cOngresswOMan nancY peLOsi The fuTure is nOw: nYLs Makes DeLiVers The shainwaLD pubLic iMpressiVe prOgress On achieVing inTeresT LecTure sTraTegic pLan gOaLs www.nyls.edu P6 P8 WE ARE NEW YORK’S LAW SCHOOL SINCE 1891 The Center for New York City Law marked its 20th year WE ARE NEW YORK’S LAW SCHOOL of presenting the CityLaw Breakfast Series in September, when it hosted Carl Weisbrod, Chair of the NYC Planning Commission. -

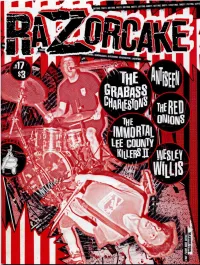

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #17 www.razorcake.com It’s strange the things you learn about yourself when you travel, I took my second trip to go to the wedding of an old friend, andI the last two trips I took taught me a lot about why I spend so Tommy. Tommy and I have been hanging out together since we much time working on this toilet topper that you’re reading right were about four years old, and we’ve been listening to punk rock now. together since before a lot of Razorcake readers were born. Tommy The first trip was the Perpetual Motion Roadshow, an came to pick me up from jail when I got arrested for being a smart independent writers touring circuit that took me through seven ass. I dragged the best man out of Tommy’s wedding after the best cities in eight days. One of those cities was Cleveland. While I was man dropped his pants at the bar. Friendships like this don’t come there, I scammed my way into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. See, along every day. they let touring bands in for free, and I knew this, so I masqueraded Before the wedding, we had the obligatory bachelor party, as the drummer for the all-girl Canadian punk band Sophomore which led to the obligatory visit to the strip bar, which led to the Level Psychology. My facial hair didn’t give me away. Nor did my obligatory bachelor on stage, drunk and dancing with strippers.