First Language Attrition in the Native Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexical Attrition of General and Special English Words After Years of Non-Exposure: the Case of Iranian Teachers

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 3; September 2010 Lexical Attrition of General and Special English Words after Years of Non-Exposure: The Case of Iranian Teachers Reza Abbasian Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Izeh Branch Islamic Azad University, Izeh, Khoozestan, Iran E-mail: Abbasian_reza @yahoo.com Yaser Khajavi (corresponding Author) Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Izeh Branch Islamic Azad University, Izeh, Khoozestan, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study sought to investigate the rate of attrition in general and special vocabulary in and out of context. Participants of the study were 210 male Persian literature teachers with different years of non-exposure to English (2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 &10) after graduating from university. They were selected through purposive sampling from among 1000 Persian literature teachers from three provinces, namely Esfahan, Fars and Yasuj. Their age ranged between 25 and 35. The instrument included one translation task. The task consisted of 20 items of general words and 20 items of special words which were tested in and out of context. Results indicated that the rate of attrition increased gradually as the years of non-exposure to English increased. Also, it was found that the rate of attrition in special and contextualized lexicon is respectively less than general and de-contextualized lexicon. Keywords: Contextualization, Attrition, General words, Special words, De-contextualization 1. Introduction “Language attrition” is the most common term used for any “Loss of language skills” that occurs after some years of non-exposure (Moorcraft & Gardner, 1987, p.327). -

The Crucial Role of Language Input During the First Year of Life

Friedmann, N., & Rusou, D. (2015). Critical period for first language: The crucial role of language input during the first year of life. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2015.06.003 Critical period for first language: The crucial role of language input during the first year of life Naama Friedmann and Dana Rusou Language and Brain Lab, Tel Aviv University The critical period for language acquisition is often explored in the context of second language acquisition. We focus on a crucially different notion of critical period for language, with a crucially different time scale: that of a critical period for first language acquisition. We approach this question by examining the language outcomes of children who missed their critical period for acquiring a first language: children who did not receive the required language input because they grew in isolation or due to hearing impairment and children whose brain has not developed normally because of thiamine deficiency. We find that the acquisition of syntax in a first language has a critical period that ends during the first year of life, and children who missed this window of opportunity later show severe syntactic impairments. The critical period for language acquisition is often explored in the context of second language acquisition. Most studies and theories of the critical period for language ask until when children and adolescents can acquire a language effortlessly and accurately like a first language, given that they have already been exposed to a first language, and acquired it (or started acquiring it). This question received various ages as an answer, mostly revolving around puberty ages. -

L1 Attrition and the Mental Lexicon Monika Schmid, Barbara Köpke

L1 attrition and the mental lexicon Monika Schmid, Barbara Köpke To cite this version: Monika Schmid, Barbara Köpke. L1 attrition and the mental lexicon. Pavlenko, Aneta. The Bilin- gual Mental Lexicon. Interdisciplinary approaches, Multilingual Matters, pp.209-238, 2009, Bilingual Education & Bilingualism, 978-1-84769-124-8. hal-00981094 HAL Id: hal-00981094 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00981094 Submitted on 20 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 9 L1 attrition and the mental lexicon Monika S. Schmid, Rijksuniversiteit, Groningen & Barbara Köpke, Université de Toulouse – Le Mirail Introduction The bilingual mental lexicon is one of the most thoroughly studied domains within investigations of bilingualism. Psycholinguistic research has focused mostly on its organization or functional architecture, as well as on lexical access or retrieval procedures (see also Meuter, this volume). The dynamics of the bilingual mental lexicon have been investigated mainly in the context of second language acquisition (SLA) and language pathology. Within SLA, an important body of research is devoted to vocabulary learning and teaching (e.g. Bogaards & Laufer, 2004; Ellis, 1994; Hulstijn & Laufer, 2001; Nation, 1990, 1993). In pathology, anomia (i.e. -

The Critical Period Hypothesis for L2 Acquisition: an Unfalsifiable Embarrassment?

languages Review The Critical Period Hypothesis for L2 Acquisition: An Unfalsifiable Embarrassment? David Singleton 1 and Justyna Le´sniewska 2,* 1 Trinity College, University of Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; [email protected] 2 Institute of English Studies, Jagiellonian University, 31-120 Kraków, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article focuses on the uncertainty surrounding the issue of the Critical Period Hy- pothesis. It puts forward the case that, with regard to naturalistic situations, the hypothesis has the status of both “not proven” and unfalsified. The article analyzes a number of reasons for this situation, including the effects of multi-competence, which remove any possibility that competence in more than one language can ever be identical to monolingual competence. With regard to the formal instructional setting, it points to many decades of research showing that, as critical period advocates acknowledge, in a normal schooling situation, adolescent beginners in the long run do as well as younger beginners. The article laments the profusion of definitions of what the critical period for language actually is and the generally piecemeal nature of research into this important area. In particular, it calls for a fuller integration of recent neurolinguistic perspectives into discussion of the age factor in second language acquisition research. Keywords: second-language acquisition; critical period hypothesis; age factor; ultimate attainment; age of acquisition; scrutinized nativelikeness; multi-competence; puberty Citation: Singleton, David, and Justyna Le´sniewska.2021. The Critical Period Hypothesis for L2 Acquisition: An Unfalsifiable 1. Introduction Embarrassment? Languages 6: 149. In SLA research, the age at which L2 acquisition begins has all but lost its status https://doi.org/10.3390/ as a simple quasi-biological attribute and is now widely recognized to be a ‘macrovari- languages6030149 able’ (Flege et al. -

Second Language Acquisition and First Language Phonological Modification

Second Language Acquisition and First Language Phonological Modification Gillian Lord University of Florida 1. Introduction While many second language (L2) acquisition studies analyze the effects that the first language (L1) has on L2 development, less common are studies that examine the converse situation: does acquisition of an L2 impact the L1? This study examines the effects of L2 acquisition on L1 use by looking at the L1 phonological productions of advanced L2 learners vis-à-vis the production of monolingual speakers of the same languages. While most research on L1 phonological modification focuses on speakers who lose their L1 as a result of becoming members of bilingual communities and reside in the L2 community, few studies investigate L2 speakers that remain in their L1 community. This pilot study project begins to fill in the picture of L1 attrition by investigating the modifications of advanced L2 learners of Spanish who remain in their L1 (English) community (the US). It has been documented that L2 speakers are invariably influenced, to some degree, by their L1. However, following Flege’s (1987, 2005) Merger Hypothesis, it is proposed that the merging of phonetic properties of phones that are similar in the L1 and L2 can potentially impact not only the acquired language but the native one as well. In other words, an English speaker with advanced proficiency in Spanish could not only pronounce Spanish with an English characteristics, but will also pronounce English words less “English-like” than a monolingual English speaker would. While this has been shown in French-English bilinguals (i.e., Flege 1987), corroborating evidence from Spanish- English bilinguals has been lacking (Flege 2005). -

Language Attrition: the Next Phase Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid

Language Attrition: The next phase Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid To cite this version: Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid. Language Attrition: The next phase. Monika S. Schmid, Barbara Köpke, Merel Keijzer, Lina Weilemar. First Language Attrition: Interdisciplinary perspectives on methodological issues, John Benjamins, pp.1-43, 2004, Studies in Bilingualism, 9027241392. hal- 00879106 HAL Id: hal-00879106 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00879106 Submitted on 31 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Language Attrition: The Next Phase Barbara Köpke (Université de Toulouse – Le Mirail) and Monika S. Schmid Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Barbara Köpke Laboratoire de Neuropsycholinguistique Jacques Lordat Institut des Sciences du Cerveau de Toulouse Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail 31058 Toulouse Cedex France [email protected] Monika S. Schmid Engelse Taal en Cultuur Faculteit der Letteren Vrije Universiteit 1081 HV Amsterdam The Netherlands [email protected] Published in : M.S. Schmid, B. Köpke, M. Keijzer & L. Weilemar (2004). First Language Attrition. Interdisciplinary perspectives on methodological issues (pp. 1-43). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Köpke, B. & Schmid, M.S. (2004). Language Attrition: The Next Phase. In M.S. Schmid, B. -

First Language Loss in Spanish-Speaking Children Patterns of Loss and Implications for Clinical Practice

Excerpted from Bilingual Language Development and Disorders in Spanish-English Speakers, Second Edition Edited by Brian A. Goldstein, Ph.D., CCC-SLP 10 First Language Loss in Spanish-Speaking Children Patterns of Loss and Implications for Clinical Practice Raquel T. Anderson One of the most salient linguistic characteristics of immigrant populations across the world is that in language contact situations, fi rst language (L1) skills will be aff ected. How these skills are changed in terms of structure and degree depends on a myriad of variables. Latino children living in the United States are not immune to this phenomenon, and practitioners coping with the complexities of assessing and treating children from dual language envi- ronments need to understand the phenomenon and how it is manifested in the children’s use of Spanish, which is oft en their L1. Not understanding language contact phenomena may result in incorrectly interpreting performance, thus increasing the potential for the misdiagnosis of language ability or disability. Th e purpose of this chapter is to describe Spanish-speaking children’s patterns of use of their L1 as they begin to learn to use their second language (L2), which, in the United States, is usually English. In particular, the phenomenon of fi rst language loss in children is described, with a particular emphasis on Spanish. By understanding what is known about L1 loss and how it is manifested in Spanish-speaking children, speech-language patholo- gists will be able to interpret L1 skill in the context of L1 loss and thus discern true disability in this population. -

The Theoretical Significance of Research on Language Attrition for Understanding Bilingualism

The theoretical significance of research on language attrition for understanding bilingualism Monika S. Schmid Rijksuniversiteit Groningen [email protected] Abstract: The most important and most controversial issue for bilingualism research is the question why children are better at language learning than adults: while all normally developing children reach fully native speaker proficiency, foreign language learners hardly ever do. Researchers disagree as to whether this age effect is due to language-specific neurobiological and maturational processes or to more general factors linked to cognitive development and the competition of two language systems in the bilingual mind. As both scenarios predict non-native like behavior of second language (L2) learners, it has to date been impossible to conclusively establish which of them actually obtains. I propose that new insights can be provided by including first language (L1) attriters in the comparison: migrants who are using their L2 dominantly, and whose L1 is consequently deteriorating. These speakers acquired their L1 without maturational constraints, but they experience the same impact of bilingualism and competition between languages as L2 learners do. They therefore provide a source of data that is non-native for reasons which are known. If attaining native speaker proficiency is maturationally constrained, processing strategies should remain native-like in an L1 which has become non-dominant. If the persistent problems of L2 learners are due to issues such as lack of exposure and competition between languages, attriters should become more similar to foreign- language learners than to natives. Key words: Language attrition, Critical period, Late L2 learning 1. Age and bilingual development Qualitative vs. -

Apt Ratner Cv May 2020.Pdf

Curriculum Vitae Notarization. I have read the following and certify that this curriculum vitae is a current and accurate statement of my professional record. Signature____________________ Date: May 2020__________ Personal Information A. UID nratner, Ratner, Nan Bernstein 0141GG Lefrak Hall, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 Mailing address: 0100 Lefrak Hall 301-405-4217, 301-314-2023 (fax) [email protected] https://hesp.umd.edu/facultyprofile/Bernstein%20Ratner/Nan ORCID iD 0000-0002-9947-0656; link to my public record: http://orcid.org/0000-0002- 9947-0656 Google Scholar profile: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C21&q=Nan+Bernstein+Ratner& btnG= B. Academic Appointments at UMD Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Assistant Professor (1983-1989) Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Associate Professor (1989-1999) Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Professor (1999 – present) (1993 - 2014) C. Administrative Appointments at UMD Chairman, Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences (1993-2014) D. Other employment 1982 - 1983 Howard University Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Communication Sciences 1978 - 1982 Boston College Instructor, Department of Special Education 1978 - 1982 University of Massachusetts, Boston (formerly Boston State College) Instructor, Depts. of Psychology and Special Education 1980 - 1982 Bridgewater State College, MA Instructor, Department of Communication Disorders 1977 - 1981 Tufts University Director, Forensics Program Intercollegiate Varsity Debate Coach Instructor, Experimental College 1977 - 1978 Child Development Center, Brockton, MA Director, Speech and language services 1977 - 1978 Southeast Massachusetts Head Start, Brockton, MA Director, Speech and language services E. Educational Background Boston University 1982 Ed.D. Applied Psycholinguistics Temple University 1976 M.A. -

Vocabulary Attrition Among Adult English As a Foreign Language Persian Learners

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 3, No. 4; December 2010 Vocabulary Attrition among Adult English as A Foreign Language Persian Learners Azadeh Asgari (Corresponding author) C-3-22, Selatan Perdana, Taman Serdang perdana, Seri Kembangan Serdang, PO box 43300, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 60-17-350-7194 E-mail: [email protected] Ghazali Bin Mustapha Department of Language and Humanities, Faculty of Educational Studies Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia Tel: 60-19-650-8340 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study aims to investigate the attrition rate of EFL concrete and abstract vocabulary among continuing and non-continuing Iranian female and male English language learners across different proficiency levels. They are students of a University and majored in different fields (between 20 and 25 years old). There was no treatment in this study where the researcher compared two groups on the same variables. Hence, the design of the current study is an ex-post facto design. A 40-item vocabulary test which varied across two proficiency levels are used to measure rate of vocabulary attrition as the instrument of this research. In the two stages, after an interval of three months, the students are taken the same tests. The results revealed that there was no significant difference between EFL attrition rate of abstract and concrete nouns among the continuing students across different proficiency levels. However, this hypothesis was rejected for the non-continuing learners at intermediate and advanced proficiency level. Keywords: Vocabulary attrition, Abstract and concrete nouns, Continuing and non-continuing students, Proficiency level Introduction The study of language attrition has recently emerged as a new field of study. -

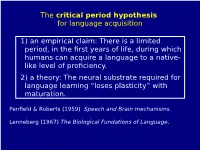

The Critical Period Hypothesis for Language Acquisition 1) an Empirical Claim: There Is a Limited Period, in the First Years Of

The critical period hypothesis for language acquisition 1) an empirical claim: There is a limited period, in the first years of life, during which humans can acquire a language to a native- like level of proficiency. 2) a theory: The neural substrate required for language learning “loses plasticity” with maturation. Penfield & Roberts (1959) Speech and Brain mechanisms. Lenneberg (1967) The Biological Fundations of Language. “Language acquisition circuitry is not needed once it has been used. It should be dismantled if keeping it around incurs any cost [...] Greedy neural tissue lying around beyond its point of usefulness is a good candidate for the recycling bin.” Pinker, 1994, The Language Instinct. Note that there several possible explanations: - maturationnal constraints (“loss of plasiticity”) - “use it then lose it” - “use it or lose it” (Tom Bever) Critical Periodes in Animals ● Effect of visual deprivation on ocular dominance – Hubel & Wiesel (1965) Comparison of the effects of unilateral and bilateral eye closure on cortical unit responses in kittens. J Neurophysiology. ● Song learning in sparrows – Marler & Peters (2010) A Sensitive Period for Song Acquisition in the Song Sparrow, Melospiza melodia: A Case of Age- limited Learning. Ethology ● Plasticity of auditory space map: – Knudsen EI, Knudsen PF (1990) Sensitive and critical periods for visual calibration of sound localization by barn owls. J Neurosci. Knudsen and Knudsen, 1990 ● Owls equipped with prismatic spectacles within the first month of life exhibited large adaptive shifts in auditory orienting behavior, whereas owls equipped with prisms as adults did not. ● The capacity of abnormal vision to alter sound localization declined to adult levels by 70–100 d of age. -

Variables and Mechanisms Affecting Response to Language Treatment

behavioral sciences Review Variables and Mechanisms Affecting Response to Language Treatment in Multilingual People with Aphasia Mira Goral 1,2,* and Aviva Lerman 3 1 Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, Graduate Center & Lehman College, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016, USA 2 MultiLing Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan, University of Oslo, 0313 Oslo, Norway 3 Program of Communication Disorders, Hadassah Academic College, Jerusalem 9101001, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 August 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020; Published: 22 September 2020 Abstract: Background: Despite substantial literature exploring language treatment effects in multilingual people with aphasia (PWA), inconsistent results reported across studies make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Methods: We highlight and illustrate variables that have been implicated in affecting cross-language treatment effects in multilingual PWA. Main contribution: We argue that opposing effects of activation and inhibition across languages, influenced by pertinent variables, such as age of language acquisition, patterns of language use, and treatment-related factors, contribute to the complex picture that has emerged from current studies of treatment in multilingual PWA. We propose a new integrated model—Treatment Effects in Aphasia in Multilingual people (the TEAM model)—to capture this complexity. Keywords: language activation; language inhibition; language treatment; cross-language generalization; stroke aphasia 1. Introduction This paper addresses the variables and mechanisms that affect efficacy of language treatment provided for multilingual people who acquire language impairments (aphasia). Our aim is to shed light on a complex phenomenon and to reflect on the mixed patterns of findings regarding cross-language response to intervention reported to date.