1 CHAPTER 3 TEMPERATURE 3.1 Introduction During Our Studies of Heat and Thermodynamics, We Shall Come Across a Number of Simple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemmatters December 2006 Reading Strategies

December 2006 Teacher's Guide About the Guide...............................................................................................................................3 Student Questions .........................................................................................................................4 Answers to Student Questions.............................................................................................5 Puzzle: Chemistry Drop-outs .................................................................................................7 Answers to Puzzle: Chemistry Drop-outs ....................................................................8 Content Reading Guide ......................................................................................................................9 National Science Education Content Standard Addressed.......................................................................9 Anticipation Guides ...........................................................................................................................10 Corn-the A’maiz’ing Grain .......................................................................................................................10 Sticky Situations: the Wonders of Glue...................................................................................................11 Unusual Sunken Treasure.......................................................................................................................12 Thermometers .........................................................................................................................................13 -

How Cold Is Cold: What Is Temperature?

How_Cold_is_Cold:_What_is_Temperature? Hi. My name is Rick McMaster and I work at IBM in Austin, Texas. I'm the STEM advocate and known locally as Dr. Kold because of the work that I do with schools in central Texas. Think about this question. Was it cold today when you came to school? Was it hot? We'll come back to that shortly, but let's start with something that I think we would all agree is cold, ice. Here's a picture of a big piece of ice. An iceberg, in fact. Now take a few minutes to discuss how much of the iceberg you see above the water, and why this happens. Welcome back. The density of water is about 0.92 grams per cubic centimeter, and sea water about 1.025. If we divide the first by the second, you see that about 90% of the iceberg is below the surface, something for a ship to watch out for. Why did we start with density and not temperature? Density is something that's a much more common experience. If something floats in water, it's less dense than water. If it sinks, it's more dense. That can't be argued. Let's take a little more time to talk about water and ice because it will be important later. So why is ice less dense than water? The solid form of water forms hexagonal crystals with the Hydrogen atoms shown in white, forming bonds with neighboring Oxygen atoms in red. With the water molecules no longer able to move readily, the ice is less dense and the iceberg floats. -

Structural and Thermal Analysis on Composite

Vol.2, No.1 ISSN Number (online): 2454-9614 Proceedings of International Conference on Recent Trends in Mechanical Engineering-2K15(NECICRTME-2K15), 20th – 21st November,2015 STRUCTURAL AND THERMAL ANALYSIS ON COMPOSITE CYLINDER 1 K.Swaroop Kumar, 2 K.Kiran Chand 1 M.Tech Student, Narasaraopeta Engineering College, JNTU Kakinada 2 Assistant Professor, Narasaraopeta Engineering College, JNTU Kakinda 1 [email protected] 3 [email protected] Abstract: Fiber reinforced composites due to their high 1.2 Cryogenics stiffness to weight ratio and strength to weight ratio are being considered for liquid nitrogen cylinders. Tests The branches of physics and engineering that involve have been shown that graphite/epoxy composites have the study of very low temperatures, how to produce tendency to micro crack at very low temperatures. In the them, and how materials behave at those temperatures. case of cylinders these micro cracks can act as passages for the cryogenic liquid to penetrate which could 1.3 Industrial applications ultimately lead to failure of the whole structure, hence it is very important to understand the fracture behavior of Liquefied gases, such as liquid nitrogen and liquid fibre composites at cryogenic temperatures before they helium, are used in many cryogenic applications. Liquid are used in cryogenic storage systems. nitrogen is the most commonly used element in cryogenics and is legally purchasable around the world. Earlier research are focused on the effect of Liquid helium is also commonly used and allows for the higher temperatures on the behavior of composites, very lowest attainable temperatures to be reached. little research is made to determine the low temperatures response of composites. -

Thermodynamic Temperature

Thermodynamic temperature Thermodynamic temperature is the absolute measure 1 Overview of temperature and is one of the principal parameters of thermodynamics. Temperature is a measure of the random submicroscopic Thermodynamic temperature is defined by the third law motions and vibrations of the particle constituents of of thermodynamics in which the theoretically lowest tem- matter. These motions comprise the internal energy of perature is the null or zero point. At this point, absolute a substance. More specifically, the thermodynamic tem- zero, the particle constituents of matter have minimal perature of any bulk quantity of matter is the measure motion and can become no colder.[1][2] In the quantum- of the average kinetic energy per classical (i.e., non- mechanical description, matter at absolute zero is in its quantum) degree of freedom of its constituent particles. ground state, which is its state of lowest energy. Thermo- “Translational motions” are almost always in the classical dynamic temperature is often also called absolute tem- regime. Translational motions are ordinary, whole-body perature, for two reasons: one, proposed by Kelvin, that movements in three-dimensional space in which particles it does not depend on the properties of a particular mate- move about and exchange energy in collisions. Figure 1 rial; two that it refers to an absolute zero according to the below shows translational motion in gases; Figure 4 be- properties of the ideal gas. low shows translational motion in solids. Thermodynamic temperature’s null point, absolute zero, is the temperature The International System of Units specifies a particular at which the particle constituents of matter are as close as scale for thermodynamic temperature. -

Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics

CHEMICAL ENGINEERING THERMODYNAMICS Andrew S. Rosen SYMBOL DICTIONARY | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Symbol Dictionary ........................................................................................................................ 3 1. Measured Thermodynamic Properties and Other Basic Concepts .................................. 5 1.1 Preliminary Concepts – The Language of Thermodynamics ........................................................ 5 1.2 Measured Thermodynamic Properties .......................................................................................... 5 1.2.1 Volume .................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2.2 Temperature ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2.3 Pressure .................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Equilibrium ................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3.1 Fundamental Definitions .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.3.2 Independent and Dependent Thermodynamic Properties ........................................................................ 7 1.3.3 Phases ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Hot Lips, a Cold Heart and Thermomometry

[e)n§lviews and opinions HOT LIPS, A COLD HEART AND THERMOMOMETRY OCTAVE LEVENSPIEL Oregon State University adopted, master instrument maker, and traveller. Corvallis, Oregon 97331 While in Copenhagen in 1704 or 5 ( or maybe 6) he visited Ole R<f:>mer, Danish astronomer, where ORIGIN OF THE THERMOMETER, a THE he observed him busily calibrating thermometers. device with some sort of scale for measuring Struck by the elegant simplicity of R<f>mer's choice the hotness or coldness of objects, is obscure. of calibration points ... 7½ 0 for the ice-water However, the climate in Europe in the beginning and 22½ 0 for body temperature, Gabe immedi 1600's was hot for it, it had to be invented at that ately adopted these for his own. But since frac time, and so it was . but by whom? In Italy tions always bothered him he eventually multi Galileo had his champions, and so had Santorio, plied everything by 4 to get rid of the two halves, Professor of Medicine at Padua. Then there was fudged upward a bit, and ended up with 32° and the Welsh doctor and religious nut Fludd; also 96 ° for these calibration points. On this scale a the gadgeteer, inventor, and perpetual-motion mixture of sea salt and ice melted at about 0° and machine-maker, Drebbel of Holland. But who was first? Since people in those days didn't much care about getting into the Guinness Book of Records we probably will never satisfactorily resolve this The temperature measures the "quantity of heat" question. -

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Temperature

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Temperature Our thanks to Hakko for allowing us to reprint the following article. By Granpa Curmudgeon There are five — count them — five temperature scales: All these people are dead, now. This is old news, but good. 1. Kelvin (oK) - after William Thompson Kelvin, 1st Baron Kelvin, who had cold feet (an occupational THE BASIC AND UNDYING RELATIONSHIP OF ALL hazard of living in Belfast, especially 100 years ago). THESE SILLY THINGS TO EITHER OTHER: He did a lot of things, some of which were useful, and in his honour the Kelvin scale of absolute x oK = (x-273.15) oC = (1.25)(x-273.15) oRè = (1.8)x - temperature (related to Celsius) was named for him. 459.67 oF = (1.8)x oR. Things all start at 0o K. and go up from there. Got that? 2. Rankine (oR) - after William John Macquorn Rankine. Rankine was born in Edinburgh, died in Most of us only care about Celsius and Fahrenheit Glasgow, and cared about thermodynamics between scales. The Fahrenheit scale (the one we grew up with) times. The Rankine scale uses the smaller is, of course, as American as pepperoni pizza, Toyota Fahrenheit degree for measurement - appropriate pickups, and the Beatles. for a frugal Scot - and is another absolute temperature scale, as if we needed two of them. 3. Celsius (oC) - formerly, and more appropriately, 'centigrade', but Anders Celsius needed to have something named after him, too, so there you are. 4. Fahrenheit (oF) - after Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, who somehow got the idea that water froze at 32 degrees and boiled at something higher. -

1 a Brief History of Thermometry History: the Thermoscope History: the Galileo Thermometer History: the Hook Thermometer Fahrenh

A Brief History of ThermometrySource: http://val.gsfc.nasa.gov/projects/modis_sst/index.html History: The Thermoscope Designed by Galileo (1597) Something similar built by Santorio (1612) Problem: It responds to changes in pressure. It’s also a barometer! MODIS SST Imagery Dr. Christopher M. Godfrey University of North Carolina at Asheville ATMS 320 ATMS 320 History: The Galileo Thermometer History: The Hook Thermometer Also termometro lentos Robert Hook developed an alcohol (“spirit”) Ferdinand II built the first Galileo thermometer with a scale (1664) thermometer (1641) Each “degree” represents 1/500 of the Each ball has a weight-to-volume ratio volume of liquid at the freezing point of water such that it will rise or fall in a (which is zero degrees) hydrocarbon fluid as the density of the First intelligible meteorological records use fluid changes this scale When fluid is less dense, balls will sink When fluid is more dense, balls will rise ATMS 320 ATMS 320 Fahrenheit Scale (°F) Réaumur Scale (°Ré, °Re, or °R) 1724: 1731: 0° = Temperature of sea salt, ice, and water An 80-point scale 30° = Temperature of ice and water 80°R = boiling point of water 96° = Temperature “obtained if the thermometer is placed 0°R = freezing point of ice in the mouth so as to acquire the heat of a healthy man” Used mercury thermometers Stories differ on the original definition for the scale Boiling point of water = 212°F Old European data may use °R Freezing point later (i.e., within Fahrenheit’s lifetime) Why 80°? adjusted to 32°F -

Chapter 1 Getting Started

c01GerringStarted.indd Page 1 9/6/17 8:47 PM f-512 /208/WB02168_PRINT/XXXXXXXXXXXXX/bmmatter CHAPTER 1 Getting Started Introductory Concepts and Definitions © digitalskillet/iStockphoto Medical professionals rely on measurements of pressure and temperature, introduced in Secs. 1.6 and 1.7. Engineering Context LEARNING OUTCOMeS When you complete your study of this Although aspects of thermodynamics have been studied since ancient chapter, you will be able to... times, the formal study of thermodynamics began in the early nineteenth century through consideration of the capacity of hot objects to produce • Explain several fundamental concepts used work. Today the scope is much larger. Thermodynamics now provides throughout the book, including closed essential concepts and methods for addressing critical twenty-first-century system, control volume, boundary and issues, such as using fossil fuels more effectively, fostering renewable surroundings, property, state, process, the energy technologies, and developing more fuel-efficient means of trans- distinction between extensive and intensive portation. Also critical are the related issues of greenhouse gas emissions properties, and equilibrium. and air and water pollution. Thermodynamics is both a branch of science and an engineering • Identify SI and English Engineering units, specialty. The scientist is normally interested in gaining a fundamental including units for specific volume, pressure, understanding of the physical and chemical behavior of fixed quantities and temperature. of matter at rest and uses the principles of thermodynamics to relate the • Describe the relationship among the Kelvin, sys- properties of matter. Engineers are generally interested in studying Rankine, Celsius, and Fahrenheit temperature tems and how they interact with their surroundings. -

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics What is it? Why do we study it? Thermodynamics Science dealing with how Matter behaves in relation to heat and work exchanged with the surroundings. Thermodynamics Science dealing with how Matter behaves in relation to heat and work exchanged with the surroundings. Phases of Matter - Solid (ES2001 Materials), Liquids (ES3001), Gases (ES3001), Plasma (Graduate School) Applications of Thermodynamics: (See Table 1.1 of text - huge!) Thermodynamics The Design and Analysis of many engineering systems requires thermodynamics (in addition to fluid mechanics, heat transfer, structural analysis, etc.). Another short description of Thermodynamics is: Link Location: http://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/Science-Stories/Science-Made-Simple/Sci-Media/Video/Thermodynamics Course Objectives: Thermodynamics is both a branch of science and a specialty within engineering. In this course you will be introduced to properties of matter (Temperature, Pressure, Enthalpy, Specific Volume, Entropy, etc.) and governing laws which can be used to describe the behavior of matter and its interaction with the surrounding environment. Course Objectives: Thermodynamics is both a branch of science and a specialty within engineering. In this course you will be introduced to properties of matter (Temperature, Pressure, Enthalpy, Specific Volume, Entropy, etc.) and governing laws which can be used to describe the behavior of matter and its interaction with the surrounding environment. You will learn how to identify systems and to use thermodynamic analysis to describe the behavior of the system in terms of properties and processes. Understanding how to apply these concepts is a powerful tool for the engineer, enabling the evaluation of material states (phases) under different conditions and the maximum efficiency achievable with various power cycles. -

Substance Data Sheet – Conversions

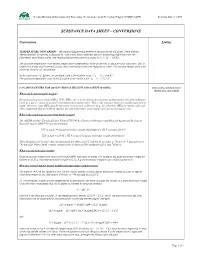

Nevada Division of Environmental Protection, Chemical Accident Prevention Program (NDEP-CAPP) Revision Date: 11/2/07 SUBSTANCE DATA SHEET – CONVERSIONS Conversions Link(s) TEMPERATURE CONVERSION – Mechanical Engineering Reference Manual for the PE Exam, Tenth Edition, Thermodynamic Properties of Substances - The scales most commonly used for measuring temperature are the Fahrenheit and Celsius scales. The relationship between these two scales is T°F = 32° + (9/5)T°C. The absolute temperature scale defines temperature independently of the properties of any particular substance. This is unlike the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales, which are based on the freezing point of water. The absolute temperature scale should be used for all calculations. In the customary U.S. System, the absolute scale is the Rankine scale: T°R = T°F + 459.67°. The absolute temperature scale in the SI system is the Kelvin scale: TK = T°C +273.15°. CANADIAN CENTRE FOR OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY (CCOHS) – www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/ chemicals/convert.html When can I convert mg/m3 to ppm? Occupational exposure limits (OELs, TLVs, PELs, etc.) can be expressed in parts per million (ppm) only if the substance exists as a gas or vapour at normal room temperature and pressure. This is why exposure limits are usually expressed in mg/m3. However, some OELs may be expressed in units such as fibres/cc (e.g., for asbestos). OELs for metals, salts and other compounds that do not form vapours at room temperature and pressure are expressed in mg/m3 only. What is the usual way of converting mg/m3 to ppm? The ACGIH booklet "Threshold Limit Values (TLVs™) for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents and Biological Exposure Indices (BEIs™)" uses the formulas: TLV in mg/m3 = [(gram molecular weight of substance) x (TLV in ppm)]/(24.45) TLV in ppm = [24.45 x (TLV in mg/m3)]/(gram molecular weight of substance) These formulas can be used when measurements are taken at 25°C and the air pressure is 760 torr (= 1 atmosphere or 760 mm Hg). -

Cryogenics - an Engineering Tool for Textiles and Apparel

Volume 8, Issue 1, Spring 2013 Cryogenics - An Engineering Tool for Textiles and Apparel M. Parthiban, M.R. Srikrishnan and S. Viju Department of Fashion, Textile Technology PSG College of Technology ABSTRACT Cryogenics is the study of the production of very low temperature (below −150 °C, −238 °F or 123 K) and the behavior of materials at those temperatures. The word cryogenics stems from Greek and means "the production of freezing cold"; however, the term is used today as a synonym for the low-temperature state. A person who studies elements under extremely cold temperature is called a cryogenicist. Rather than the relative temperature scales of Celsius and Fahrenheit, cryogenicists use the absolute temperature scales. These are Kelvin (SI units) or Rankine scale (Imperial & US units). It is not well-defined at what point on the temperature scale refrigeration ends and cryogenics begins, but most scientists assume it starts at or below -150 °C or 123 K (about -240 °F). The National Institute of Standards and Technology at Boulder, Colorado has chosen to consider the field of cryogenics as that involving temperatures below −180 °C (-292 °F or 93.15 K). This is a logical dividing line, since the normal boiling points of the so-called permanent gases (such as helium, hydrogen, neon, nitrogen, oxygen, and normal air) lie below −180 °C while the Freon refrigerants, hydrogen sulfide, and other common refrigerants have boiling points above −180 °C. Keywords: cryogenics, material freezing, refrigeration Introduction condition1. Aging, disease, and damage due to cooling low temperature are all Cryogenics is low temperature potentially things that can be repaired by physics: "The branches of physics and nanotechnology and other future molecular engineering that involve the study of very repair technologies.