Discrete Geometry and Projections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg**- Compact Spaces

International Journal of Mathematics Research. ISSN 0976-5840 Volume 9, Number 1 (2017), pp. 27-43 © International Research Publication House http://www.irphouse.com pg**- compact spaces Mrs. G. Priscilla Pacifica Assistant Professor, St.Mary’s College, Thoothukudi – 628001, Tamil Nadu, India. Dr. A. Punitha Tharani Associate Professor, St.Mary’s College, Thoothukudi –628001, Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract The concepts of pg**-compact, pg**-countably compact, sequentially pg**- compact, pg**-locally compact and pg**- paracompact are introduced, and several properties are investigated. Also the concept of pg**-compact modulo I and pg**-countably compact modulo I spaces are introduced and the relation between these concepts are discussed. Keywords: pg**-compact, pg**-countably compact, sequentially pg**- compact, pg**-locally compact, pg**- paracompact, pg**-compact modulo I, pg**-countably compact modulo I. 1. Introduction Levine [3] introduced the class of g-closed sets in 1970. Veerakumar [7] introduced g*- closed sets. P M Helen[5] introduced g**-closed sets. A.S.Mashhour, M.E Abd El. Monsef [4] introduced a new class of pre-open sets in 1982. Ideal topological spaces have been first introduced by K.Kuratowski [2] in 1930. In this paper we introduce 28 Mrs. G. Priscilla Pacifica and Dr. A. Punitha Tharani pg**-compact, pg**-countably compact, sequentially pg**-compact, pg**-locally compact, pg**-paracompact, pg**-compact modulo I and pg**-countably compact modulo I spaces and investigate their properties. 2. Preliminaries Throughout this paper(푋, 휏) and (푌, 휎) represent non-empty topological spaces of which no separation axioms are assumed unless otherwise stated. Definition 2.1 A subset 퐴 of a topological space(푋, 휏) is called a pre-open set [4] if 퐴 ⊆ 푖푛푡(푐푙(퐴) and a pre-closed set if 푐푙(푖푛푡(퐴)) ⊆ 퐴. -

General Topology

General Topology Tom Leinster 2014{15 Contents A Topological spaces2 A1 Review of metric spaces.......................2 A2 The definition of topological space.................8 A3 Metrics versus topologies....................... 13 A4 Continuous maps........................... 17 A5 When are two spaces homeomorphic?................ 22 A6 Topological properties........................ 26 A7 Bases................................. 28 A8 Closure and interior......................... 31 A9 Subspaces (new spaces from old, 1)................. 35 A10 Products (new spaces from old, 2)................. 39 A11 Quotients (new spaces from old, 3)................. 43 A12 Review of ChapterA......................... 48 B Compactness 51 B1 The definition of compactness.................... 51 B2 Closed bounded intervals are compact............... 55 B3 Compactness and subspaces..................... 56 B4 Compactness and products..................... 58 B5 The compact subsets of Rn ..................... 59 B6 Compactness and quotients (and images)............. 61 B7 Compact metric spaces........................ 64 C Connectedness 68 C1 The definition of connectedness................... 68 C2 Connected subsets of the real line.................. 72 C3 Path-connectedness.......................... 76 C4 Connected-components and path-components........... 80 1 Chapter A Topological spaces A1 Review of metric spaces For the lecture of Thursday, 18 September 2014 Almost everything in this section should have been covered in Honours Analysis, with the possible exception of some of the examples. For that reason, this lecture is longer than usual. Definition A1.1 Let X be a set. A metric on X is a function d: X × X ! [0; 1) with the following three properties: • d(x; y) = 0 () x = y, for x; y 2 X; • d(x; y) + d(y; z) ≥ d(x; z) for all x; y; z 2 X (triangle inequality); • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X (symmetry). -

Discrete Subspaces of Topological Spaces 1)

MATHEMATICS DISCRETE SUBSPACES OF TOPOLOGICAL SPACES 1) BY A. HAJNAL AND I. JUHASZ (Communicated by Prof. J. POPKEN at the meeting of October 29, 1966) §. l. Introduction Recently several papers appeared in the literature proving theorems of the following type. A topological space with "very many points" contains a discrete subspace with "many points". J. DE GROOT and B. A. EFIMOV proved in [2] and [4] that a Hausdorff space of power > exp exp exp m contains a discrete subspace of power >m. J. ISBELL proved in [3] a similar result for completely regular spaces. J. de Groot proved as well that for regular spaces R the assumption IRI > exp exp m is sufficient to imply the existence of a discrete subspace of potency > m. One of our main issues will be to improve this result and show that the same holds for Hausdorff spaces (see Theorems 2 and 3). Our Theorem 1 states that a Hausdorff space of density > exp m contains a discrete subspace of power >m. We give two different proofs for the main result already mentioned. The proof outlined for Theorem 3 is a slight improvement of de Groot's proof. The proof given for Theorem 2 is of purely combinatorial character. We make use of the ideas and some theorems of the so called set-theoretical partition calculus developed by P. ERDOS and R. RADO (see [5], [ 11 ]). Almost all the other results we prove are based on combinatorial theorems. For the convenience of the reader we always state these theorems in full detail. Our Theorem 4 states that if m is a strong limit cardinal which is the sum of No smaller cardinals, then every Hausdorff space of power m contains a discrete subspace of power m. -

REVERSIBLE FILTERS 1. Introduction a Topological Space X Is Reversible

REVERSIBLE FILTERS ALAN DOW AND RODRIGO HERNANDEZ-GUTI´ ERREZ´ Abstract. A space is reversible if every continuous bijection of the space onto itself is a homeomorphism. In this paper we study the question of which countable spaces with a unique non-isolated point are reversible. By Stone duality, these spaces correspond to closed subsets in the Cech-Stoneˇ compact- ification of the natural numbers β!. From this, the following natural problem arises: given a space X that is embeddable in β!, is it possible to embed X in such a way that the associated filter of neighborhoods defines a reversible (or non-reversible) space? We give the solution to this problem in some cases. It is especially interesting whether the image of the required embedding is a weak P -set. 1. Introduction A topological space X is reversible if every time that f : X ! X is a continuous bijection, then f is a homeomorphism. This class of spaces was defined in [10], where some examples of reversible spaces were given. These include compact spaces, Euclidean spaces Rn (by the Brouwer invariance of domain theorem) and the space ! [ fpg, where p is an ultrafilter, as a subset of β!. This last example is of interest to us. Given a filter F ⊂ P(!), consider the space ξ(F) = ! [ fFg, where every point of ! is isolated and every neighborhood of F is of the form fFg [ A with A 2 F. Spaces of the form ξ(F) have been studied before, for example by Garc´ıa-Ferreira and Uzc´ategi([6] and [7]). -

1. Let X Be a Non-Empty Set. Let T1 and T2 Be Two Topologies on X Such That T1 Is

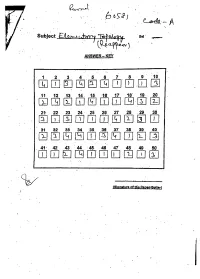

A 1 1. Let X be a non-empty set. Let T1 and T2 be two topologies on X such that T1 is strictly contained in T2. If I : (X,T1) o(X, T2) is identity map, then: (1) both I and I–1 are continuous (2) both I and I–1 are not continuous (3) I is continuous but I–1 is not continuous (4) I is not continuous but I–1 is continuous 2. The connected subset of real line with usual topology are --: (1) all intervals (2) only bounded intervals (3) only compact intervals (4) only semi-infinite intervals 3. Topological space X is locally path connected space- (1) if X is locally connected at each xX (2) if X is locally connected at some xX (3) if X is locally connected at each xX (4) None of these 4. The topology on real line R generated by left-open right closed intervals (a,b) is: (1) strictly coarser then usual topology (2) strictly finer than usual topology (3) not comparable with usual topology (4) same as the usual topology 60581/A P.T.O. A 2 5. Which of the following is not first countable? (1) discrete space (2) indiscrete space (3) cofinite topological space on R (4) metric space 6. Let X = {a,b,c} and T1= {I, {a}, {b,c}, X} X* = {x, y, z} and T2 = {I, {x}, {y,z}, X*} Then which of the following mapping from X to X* are continuous? (1) f(a) = x, f(b) = y, f(c) = z (2) g(a) = x, g(b) = y, g(c) = z (3) h(a) = z, h(b) = x, h(c) = y (4) both (1) and (2) 7. -

Discrete Topology and Geometry Algorithms for Quantitative Human Airway Trees Analysis Based on Computed Tomography Images Michal Postolski

Discrete topology and geometry algorithms for quantitative human airway trees analysis based on computed tomography images Michal Postolski To cite this version: Michal Postolski. Discrete topology and geometry algorithms for quantitative human airway trees analysis based on computed tomography images. Other. Université Paris-Est, 2013. English. NNT : 2013PEST1094. pastel-00977514 HAL Id: pastel-00977514 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00977514 Submitted on 11 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PARIS-EST UNIVERSITY DOCTORAL SCHOOL MSTIC A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science Presented by Michal Postolski Supervised by Michel Couprie and Dominik Sankowski Discrete Topology and Geometry Algorithms for Quantitative Human Airway Trees Analysis Based on Computed Tomography Images December 18, 2013 Committee in charge: Piotr Kulczycki (reviewer) Nicolas Normand (reviewer) Nicolas Passat (reviewer) Jan Sikora (reviewer) Michel Couprie Yukiko Kenmochi Andrzej Napieralski Dominik Sankowski To my brilliant wife. ii Title: Discrete Topology and Geometry Algorithms for Quantitative Human Airway Trees Analysis Based on Computed Tomography Images. Abstract: Computed tomography is a very useful technique which allow non-invasive diagnosis in many applications for example is used with success in industry and medicine. -

DISCRETE SPACETIME QUANTUM FIELD THEORY Arxiv:1704.01639V1

DISCRETE SPACETIME QUANTUM FIELD THEORY S. Gudder Department of Mathematics University of Denver Denver, Colorado 80208, U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract This paper begins with a theoretical explanation of why space- time is discrete. The derivation shows that there exists an elementary length which is essentially Planck's length. We then show how the ex- istence of this length affects time dilation in special relativity. We next consider the symmetry group for discrete spacetime. This symmetry group gives a discrete version of the usual Lorentz group. However, it is much simpler and is actually a discrete version of the rotation group. From the form of the symmetry group we deduce a possible explanation for the structure of elementary particle classes. Energy- momentum space is introduced and mass operators are defined. Dis- crete versions of the Klein-Gordon and Dirac equations are derived. The final section concerns discrete quantum field theory. Interaction Hamiltonians and scattering operators are considered. In particular, we study the scalar spin 0 and spin 1 bosons as well as the spin 1=2 fermion cases arXiv:1704.01639v1 [physics.gen-ph] 5 Apr 2017 1 1 Why Is Spacetime Discrete? Discreteness of spacetime would follow from the existence of an elementary length. Such a length, which we call a hodon [2] would be the smallest nonzero measurable length and all measurable lengths would be integer mul- tiplies of a hodon [1, 2]. Applying dimensional analysis, Max Planck discov- ered a fundamental length r G ` = ~ ≈ 1:616 × 10−33cm p c3 that is the only combination of the three universal physical constants ~, G and c with the dimension of length. -

Metric Spaces

Chapter 1. Metric Spaces Definitions. A metric on a set M is a function d : M M R × → such that for all x, y, z M, Metric Spaces ∈ d(x, y) 0; and d(x, y)=0 if and only if x = y (d is positive) MA222 • ≥ d(x, y)=d(y, x) (d is symmetric) • d(x, z) d(x, y)+d(y, z) (d satisfies the triangle inequality) • ≤ David Preiss The pair (M, d) is called a metric space. [email protected] If there is no danger of confusion we speak about the metric space M and, if necessary, denote the distance by, for example, dM . The open ball centred at a M with radius r is the set Warwick University, Spring 2008/2009 ∈ B(a, r)= x M : d(x, a) < r { ∈ } the closed ball centred at a M with radius r is ∈ x M : d(x, a) r . { ∈ ≤ } A subset S of a metric space M is bounded if there are a M and ∈ r (0, ) so that S B(a, r). ∈ ∞ ⊂ MA222 – 2008/2009 – page 1.1 Normed linear spaces Examples Definition. A norm on a linear (vector) space V (over real or Example (Euclidean n spaces). Rn (or Cn) with the norm complex numbers) is a function : V R such that for all · → n n , x y V , x = x 2 so with metric d(x, y)= x y 2 ∈ | i | | i − i | x 0; and x = 0 if and only if x = 0(positive) i=1 i=1 • ≥ cx = c x for every c R (or c C)(homogeneous) • | | ∈ ∈ n n x + y x + y (satisfies the triangle inequality) Example (n spaces with p norm, p 1). -

Ultrafilters and Tychonoff's Theorem

Ultrafilters and Tychonoff's Theorem (October, 2015 version) G. Eric Moorhouse, University of Wyoming Tychonoff's Theorem, often cited as one of the cornerstone results in general topol- ogy, states that an arbitrary product of compact topological spaces is compact. In the 1930's, Tychonoff published a proof of this result in the special case of [0; 1]A, also stating that the general case could be proved by similar methods. The first proof in the gen- eral case was published by Cechˇ in 1937. All proofs rely on the Axiom of Choice in one of its equivalent forms (such as Zorn's Lemma or the Well-Ordering Principle). In fact there are several proofs available of the equiv- alence of Tychonoff's Theorem and the Axiom of Choice|from either one we can obtain the other. Here we provide one of the most popular proofs available for Ty- chonoff's Theorem, using ultrafilters. We see this approach as an opportunity to learn also about the larger role of ultra- filters in topology and in the foundations of mathematics, including non-standard analysis. As an appendix, we also include an outline of an alternative proof of Tychonoff's Theorem using a transfinite induction, using the two-factor case X × Y (previously done in class) for the inductive step. This approach is found in the exercises of the Munkres textbook. The proof of existence of nonprincipal ultrafilters was first published by Tarski in 1930; but the concept of ultrafilters is attributed to H. Cartan. 1. Compactness and the Finite Intersection Property Before proceeding, let us recall that a collection of sets S has the finite intersection property if S1 \···\ Sn 6= ? for all S1;:::;Sn 2 S, n > 0. -

Problems in the Theory of Convergence Spaces

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Problems in the Theory of Convergence Spaces Daniel R. Patten Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Computer Sciences Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Patten, Daniel R., "Problems in the Theory of Convergence Spaces" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 152. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/152 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract. We investigate several problems in the theory of convergence spaces: generaliza- tion of Kolmogorov separation from topological spaces to convergence spaces, representation of reflexive digraphs as convergence spaces, construction of differential calculi on convergence spaces, mereology on convergence spaces, and construction of a universal homogeneous pre- topological space. First, we generalize Kolmogorov separation from topological spaces to convergence spaces; we then study properties of Kolmogorov spaces. Second, we develop a theory of reflexive digraphs as convergence spaces, which we then specialize to Cayley graphs. Third, we conservatively extend the concept of differential from the spaces of classi- cal analysis to arbitrary convergence spaces; we then use this extension to obtain differential calculi for finite convergence spaces, finite Kolmogorov spaces, finite groups, Boolean hyper- cubes, labeled graphs, the Cantor tree, and real and binary sequences. Fourth, we show that a standard axiomatization of mereology is equivalent to the condition that a topological space is discrete, and consequently, any model of general extensional mereology is indis- tinguishable from a model of set theory; we then generalize these results to the cartesian closed category of convergence spaces. -

Compactness in Metric Spaces

MATHEMATICS 3103 (Functional Analysis) YEAR 2012–2013, TERM 2 HANDOUT #2: COMPACTNESS OF METRIC SPACES Compactness in metric spaces The closed intervals [a, b] of the real line, and more generally the closed bounded subsets of Rn, have some remarkable properties, which I believe you have studied in your course in real analysis. For instance: Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem. Every bounded sequence of real numbers has a convergent subsequence. This can be rephrased as: Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem (rephrased). Let X be any closed bounded subset of the real line. Then any sequence (xn) of points in X has a subsequence converging to a point of X. (Why is this rephrasing valid? Note that this property does not hold if X fails to be closed or fails to be bounded — why?) And here is another example: Heine–Borel theorem. Every covering of a closed interval [a, b] — or more generally of a closed bounded set X R — by a collection of open sets has a ⊂ finite subcovering. These theorems are not only interesting — they are also extremely useful in applications, as we shall see. So our goal now is to investigate the generalizations of these concepts to metric spaces. We begin with some definitions: Let (X,d) be a metric space. A covering of X is a collection of sets whose union is X. An open covering of X is a collection of open sets whose union is X. The metric space X is said to be compact if every open covering has a finite subcovering.1 This abstracts the Heine–Borel property; indeed, the Heine–Borel theorem states that closed bounded subsets of the real line are compact. -

Ultrafilters and Topology

Leiden University Bachelor project Mathematics Ultrafilters and Topology Author: Supervisor: Marius Stekelenburg Dr. Owen Biesel June 13, 2014 Ultrafilters and topology Marius Stekelenburg June 13, 2014 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Ultrafilters and topology 3 2.1 Fundamental matters . .3 2.2 Convergence and topological properties . .4 2.3 Application: Tychonov’s theorem . .7 3 A categorical approach 9 3.1 Monads and algebras . .9 3.2 The ultrafilter monad . 12 3.3 Manes’ theorem . 14 4 Barr’s theorem 18 5 The Stone-Čech compactification 21 5.1 Stone-Čech compactification of discrete spaces . 21 5.2 Stone-Čech compactification of arbitrary spaces . 23 1 1 Introduction In this thesis, we will explore a simple, but rich concept, called ultrafilters. This concept has utilities in many areas, such as model theory, logic, and topology (this can be read in [2]). As the title suggests, this thesis has its focus on the latter area, topology. On topological spaces, ultrafilters can converge. Many topological prop- erties can be formulated in terms of this convergence. They work in is similar fashion to the ordinary sequence convergence, with one notable difference: it works for every topological space. This comes with a nice bonus: Tychonov’s theorem, a theorem that is otherwise hard to prove! The main result of this thesis will a reconstruction of the category of compact Hausdorff spaces. Originally proven by Ernest Manes, this con- struction enables a very different way of creating topological spaces, what will come in handy last chapter. When finding a major result, one could do two things with it: general- izing or finding an application.