Media Use As a Predictor of the Political Behaviour of Undergraduates in South-West Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

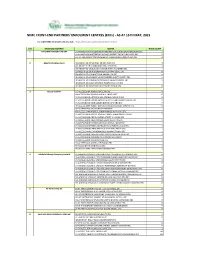

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

The 9Th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference on Africa and the African Diaspora (Tofac 2019)

The 9th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference On Africa And The African Diaspora (tofac 2019) THEME: RELIGION, THE STATE AND GLOBAL POLITICS JULY 1-3, 2019 @BABCOCK UNIVERSITY ILISHAN-REMO, OGUN STATE, NIGERIA PROGRAMME OF EVENTS FEATURING: DISTINGUISHED GUEST OF HONOUR CHIEF DR OLUSEGUN OBASANJO, GCFR, PhD Former President, Federal Republic of Nigeria CHIEF HOST PROFESSOR ADEMOLA S. TAYO HOST President/Vice-Chancellor, Babcock PROFESSOR ADEMOLA DASYLVA University Board Chair, TOFAC (International) GRAND HOST HE CHIEF DR DAPO ABIODUN, MFR Executive Governor, Ogun State, Nigeria CONFERENCE KEYNOTE SPEAKERS HE Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Sokoto, Nigeria Professor Bankole Omotoso, Writer, Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Elizade University Professor Ibigbolade Aderibigbe, Professor of Religion & Associate Director, The African Studies Institute, University of Georgia, Athens, USA BANQUET CHAIRMAN: His Imperial Majesty Fuankem Achankeng I, MA, MA, PhD The Nyatema of Atoabechied Ruler, Atoabechied, Lebialem Southwestern Cameroon & Professor, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, USA BANQUET SPECIAL GUEST OF HONOUR Professor Jide Owoeye Chairman, Governing Council & Proprietor Lead City University, Ibadan 2 NATIONAL ANTHEM Great lofty heights attain To build a nation where peace Arise, O compatriot, And justice shall reign. Nigeria’s call obey To serve our father’s land BABCOCK UNIVERSITY With love and strength and faith The labour of our heroes past ANTHEM Shall never be in vain Hail Babcock God’s own University To serve with heart and mind Built on the power of His Word One nation bound in freedom Knowledge and truth, Peace and unity Service to God and man Building a future for the youth Wholistic education, O God of creation, The vision is still aflame: Direct our noble cause Mental, physical, social, spiritual Guide our leaders right Babcock is it! Help our youths the truth to know Hail, Babcock God’s own University In love and honesty to grow Good life here and forever more. -

Statistical Report on Women and Men in Nigeria

2018 STATISTICAL REPORT ON WOMEN AND MEN IN NIGERIA NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS MAY 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... xv LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................................................................ xvi CHAPTER 1: POPULATION ....................................................................................................... 1 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 A. General Population Patterns ................................................................................................ 1 1. Population and Growth Rate ............................................................................................ -

Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD APPLICATION STATISTICS BY INTITUTION AND GENDER (AGE LESS THAN 16) S/NO INSTITUTION F M TOTAL 1 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 78 89 167 2 ACHIEVERS UNIVERSITY, OWO, ONDO STATE 3 0 3 3 ADAMAWA STATE UNIVERSITY, MUBI, ADAMAWA STATE 8 5 13 4 ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO, ONDO STATE 169 68 237 5 ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE 6 4 10 6 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO STATE. (AFFL TO OAU, ILE-IFE) 8 4 12 7 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO, ONDO STATE 1 0 1 8 AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY, ADO-EKITI, EKITI STATE 92 71 163 9 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 2 0 2 10 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 826 483 1309 11 AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, KADUNA, KADUNA STATE 2 1 3 12 AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO, OYO STATE 6 1 7 13 AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO, EBONYI STATE 5 3 8 14 AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN, AKWA IBOM STATE 39 28 67 15 AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA, AKWA IBOM STATE 7 3 10 16 ALEX EKWUEME FEDERAL UNIVERSITY, NDUFU-ALIKE, EBONYI STATE 55 33 88 17 AL-HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 3 1 4 18 AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA, KATSINA STATE 6 1 7 19 ALVAN IKOKU COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, IMO STATE, (AFFL TO UNIV OF NIGERA, NSUKKA) 3 1 4 20 AMBROSE ALLI UNIVERSITY, EKPOMA, EDO STATE 208 117 325 21 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 4 8 12 22 AMINU DABO COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KANO, KANO STATE 1 0 1 23 ANCHOR UNIVERSITY, AYOBO, LAGOS STATE -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE A. PERSONAL i. Name: ADEBAYO Yetunde Olufunmilola (Nee Ayanbadejo) ii. Date of Birth: 8th July, 1978 iii. Place of Birth: Ijebu-Ode iv. Age: 41years v. Sex: Female vi. Marital Status: Widow vii. Nationality: Nigerian viii. Town and State of Origin: Ijebu-Ode/Ogun State ix. Contact Address: Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, College of Food Science and Human Ecology, Federal University of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2240 Abeokuta. x. Phone Number: +234-80-28-169-320; +234-81-31-303-949 xi. E-mail Address: [email protected] [email protected] xii. Present Post and Salary: Lecturer II CONUASS 03/01 B. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND (i) Educational Institutions Attended with dates Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 2008-2019 University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State 2007-2009 University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 2003-2005 University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 1998-2001 Ogun State Polytechnic, Ojere, Abeokuta, Ogun State 1996-1998 Adeola Odutola College, Ijebu-Ode Ogun State 1999 Ogbogbo Baptist Grammar School, Ijebu-Ode 1995 (ii) Academic and Professional Qualifications (with dates) Ph.D. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2019 Test of Professional Competence TOPC 2015 (Institute for Dietetics in Nigeria - IDN) Post Graduate Diploma in Education 2009 M.Sc. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2005 B.Sc. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2001 ND (Food Science and Technology) 1998 Senior Secondary School Certificate 1999 1 C. WORK EXPERIENCE WITH DATE Work Experience in the University System August 2019 till date Federal University of Agriculture P. M. B. 2240 Abeokuta, Ogun State. Lecturer II (Nutrition & Dietetics Dept.) Current Job Description Lecturer II - Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State. -

African Continental Qualifications Framework MAPPING STUDY

African Continental Qualifications Framework MAPPING STUDY Country Report Working Paper NIGERIA SIFA Skills for Youth Employability Programme Author: Jacinta Ezeahurukwe Reviewer: Eduarda Castel-Branco (European Training Foundation - ETF) December 2020 This working paper on the National Qualifications Framework of Nigeria is part of the Mapping Study of qualifications frameworks in Africa, elaborated in 2020 in the context of the project AU EU Skills for Youth Employability: SIFA Technical Cooperation – Developing the African Continental Qualifications Framework (ACQF). The reports of this collection are: • Reports on countries' qualifications frameworks: Angola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Togo • Reports on qualifications frameworks of Regional Economic Communities: East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern African Development Community (SADC) Authors of the reports: • Eduarda Castel-Branco (ETF): reports Angola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Morocco, Mozambique • James Keevy (JET Education Services): report Ethiopia • Jean Adotevi (JET Education Services): reports Senegal, Togo and ECOWAS • Lee Sutherland (JET Education Services): report Egypt • Lomthie Mavimbela (JET Education Services): report SADC • Maria Overeem (JET Education Services): report Kenya and EAC • Raymond Matlala (JET Education Services): report South Africa • Teboho Makhoabenyane (JET Education Services): report South Africa • Tolika Sibiya -

MB 6Th July 2020

RSITIE VE S C NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES COMMISSION NI O U M L M A I S N S O I I O T N A N T H C E OU VI GHT AND SER MONDAY A PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY www.nuc.edu.ng th 0795-3089 6 July, 2020 Vol. 15 No. 14 NUC, Diaspora Scientists Partner On Biomedical Research On Covid-19 mid global efforts to find Suleiman Ramon-Yusuf, the ES o p p o r t u n i t i e s t h ro u g h a cure for the deadly said that the partnership was one collaborations within and Ac o r o n a v i r u s , t h e N a t i o n a l U n i v e r s i t i e s Commission (NUC) is aligning efforts with the Nigeria Diaspora Biomedical Research Group to increase the capacity of Nigerian scientists in biomedical research. Welcoming participants to the inaugural Biomedical Research Virtual Summit, the Executive Secretary, NUC, Prof. Abubakar Rasheed mni, MFR, FNAL said that the collaboration was also aimed at training the researchers on grant-writing proposals to be able to access funds at the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) and other research-funding agencies globally. Prof. Abubakar A. Rasheed Executive Secretary, NUC Represented by the Deputy of the numerous efforts by the outside Nigeria to build the Executive Secretary of NUC, Dr. c o m m i s s i o n t o e x p l o re capacity of Nigerian scientists in this edition BUK, Dantata Foods COVID-19: No Plan Sign MoU On Agric To Reopen Tertiary Research Institutions, Says PTF Pg. -

Faculty of Internal Medicine

FACULTY OF INTERNAL MEDICINE S/N AUTHOR TITLE YEA R 1. ANIDI, ANTHONY IKE Thyroid function in Breast Cancer 1976 2. OLADAPO JYTTE M.R. Case Studies in Gastroenterology 1976 3. IYUN, AYODELE Pharmacokinetic Studies in Hypertensive Patients 1979 OLUREMI 4. OLUMIDE, YETUNDE Dermatitis in the Construction Industry in Lagos 1979 MERCY 5. ADENLE, ADEBISI DA Comparison of the Assessment of Left Ventricular 1980 VID function by Ejection Fraction Using Echocardiography, Systolic Time Intervals and Cine Ventriculography 6. ANJORIN, FELIX Non-Inasive Evaluation of Aortic Valve Disease: 1980 IDOWU Comparison with Findings at Cardiac Catheterization 7. ANWUNAH, ANTHONY A Nephelometric Assay for Circulating Immune 1980 CHUKWUEMEKA Complexes Using anti-Antibody 8 AWOTEDU, ABOLADE A Casebook of Some Chronic Pulmonary 1980 AJANI Diseases 9. ODUSOTE, KAYODE The Challenge of Non-Neonatal Tetanus to a 1980 ADETOLA Developing Country 10. ODUTOLA T.A. Renal Function and Morophology in Acute Viral 1980 Hepatitis 11. OGUNLESI, TOLULOLA “A pilot Study of Serum Creative Phosphokinase 1980 OLUSESAN OLUSOLA Ensyme Changes After Clinical Exercise Testing and A case Book 12. AKINSOLA, ADEWALE Adult Nephrotic Syndrome in Ibadan 1981 A Clinco-Pathologic Study 13. OHWOVORIOLE, Urinary Cortisol Creatinine Ratio: Its Relationship 1981 AUGUSTINE E. to Hypoglycaemia and Use in the Detection of Nocturnal Hypoglycaemia in Insulin Dependent Diabetics 14. OKEKE, G.C.E. Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage 1981 15. ONYEMELUKWE, Clinical and Immunological Studies in 1981 GEOFFREY Pheumococcal Infections CHUKWUBUIKE 16. TALABI A.I. A Cardiology Case Study 1981 1 17. BOJUWOYE, Induction of Baterial Diarrhoeas by Enterocyte 1983 BABABODE JAMES Invasion as Illustrated by Yersinia Enterocolitica 18. -

Percentage of Special Needs Students

Percentage of special needs students S/N University % with special needs 1. Abia State University, Uturu 4.00 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi 0.00 3. Achievers University, Owo 0.00 4. Adamawa State University Mubi 0.50 5. Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba 0.08 6. Adeleke University, Ede 0.03 7. Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti - Ekiti State 8. African University of Science & Technology, Abuja 0.93 9. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 0.10 10. Ajayi Crowther University, Ibadan 11. Akwa Ibom State University, Ikot Akpaden 0.00 12. Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike, Ikwo 0.01 13. Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin 0.00 14. Al-Qalam University, Katsina 0.05 15. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 0.03 16. American University of Nigeria, Yola 0.00 17. Anchor University Ayobo Lagos State 0.44 18. Arthur Javis University Akpoyubo Cross River State 0.00 19. Augustine University 0.00 20. Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo 0.12 21. Bayero University, Kano 0.09 22. Baze University 0.48 23. Bells University of Technology, Ota 1.00 24. Benson Idahosa University, Benin City 0.00 25. Benue State University, Makurdi 0.12 26. Bingham University 0.00 27. Bowen University, Iwo 0.12 28. Caleb University, Lagos 0.15 29. Caritas University, Enugu 0.00 30. Chrisland University 0.00 31. Christopher University Mowe 0.00 32. Clifford University Owerrinta Abia State 0.00 33. Coal City University Enugu State 34. Covenant University Ota 0.00 35. Crawford University Igbesa 0.30 36. Crescent University 0.00 37. Cross River State University of Science &Technology, Calabar 0.00 38. -

List of Reviewers (As Per the Published Articles) Year: 2019

List of Reviewers (as per the published articles) Year: 2019 Journal of Advances in Mathematics and Computer Science ISSN: 2456-9968 Past name: British Journal of Mathematics & Computer Science ISSN: 2231-0851 (old) 2019 - Volume 30 [Issue 1] On a Hybrid Clayton-Gumbel and Gumbel-Frank Bivariate Copulas with Application to Stock Indices DOI: 10.9734/JAMCS/2019/45668 (1) Abdullah Sonmezoglu, Yozgat Bozok University, Turkey. (2) Victor Gumbo, University of Botswana, Botswana. (3) Linh H. Nguyen, Vietnam. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27837 Decomposition of Riemannian Curvature Tensor Field and Its Properties DOI: 10.9734/JAMCS/2019/43211 (1) Bilal Eftal Acet, Adıyaman University, Turkey. (2) Çiğdem Dinçkal, Çankaya University, Turkey. (3) Alexandre Casassola Gonçalves, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27899 Effect of Electric Field on MHD Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Williamson Nanofluid over a Heated Surface with Variable Thickness. OHAM Solution DOI: 10.9734/JAMCS/2019/45297 (1) Noor Saeed Khan, Abdul Wali Khan University, Pakistan. (2) Saeed Islam, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan. (3) João Batista Campos Silva, UNESP, Brazil. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27900 Viscous Dissipation Effect on Steady Natural Convection Couette Flow of Heat Generating Fluid in a Vertical Channel DOI: 10.9734/JAMCS/2019/45020 (1) M. M. Bhatti, Shanghai University, China. (2) M. G. Sobamowo, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (3) Kiran D. Devade, Pune University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/27912 Compounding Commuting Matrices DOI: 10.9734/JAMCS/2019/45969 (1) Abdullah Sonmezoglu, Bozok University, Turkey. -

Industrial Relations Practice in Nigeria: All Actors in Employment Relationships Are Accusative and Censurable

CovEnAnt UnivErsity CovEnAnt UnivEf'sity 1 6 h Inaugural Lecture BASTARDISATION OF THE TJMPLATES OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS PRACTICE IN NIGERIA: ALL ACTORS IN EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIPS ARE ACCUSATIVE AND CENSURABLE OLUFEMI J. ADEYEYE, (Ph.D) Professor ofIndustrial Relations and Human Resource Management, Department ofBusiness Management, College ofBusiness and Social Sciences A publication of Media & Corporate Affairs Dept., Covenant University, Km. 10 ldiroko Road, Canaan Land, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria Tel: +234-014542070 Website: www.covenantuniversity.edu.ng Covenant University Press, Km. 10 ldiroko Road, Canaan Land, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria /SSN 2006 ... 0327 Inaugural Lecture Series. Vol. 5, No. 2, March, 2016 f OLUFEMI J. ADEYEYE Ph.D Professor of Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management, Department of Business Management, College of Business and Social Sciences Bastardisation of the Templates of Industrial Relations Practice in Nigeria: All Actors in Employment Relationships are Accusative and Censurable (I) COURTESIES Chancellor, Vice-Chancellor, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Registrar, Other Principal Officers of the University, Deans of Colleges, Eminent Professors, Invited Guests, My beloved Relations and Friends, Gentlemen and Ladies of the Press, The Entire Faculty, Staff and Students, Ladies and Gentlemen. (II) AT THE BEGINNING As a young boy with visible features of tallness, I heard my mother say, “Olufemi, ise oye enigun” –meaning “poverty is not in any way favourable to the stature of a tall man.” With this admonition from an amicable mother, I engaged all that was lawful and humanly possible by way of hard work, to defy poverty to a reasonable extent. Mr. -

Olabisi Onabanjo University Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria Format B Curricullum Vitae and Annual Appraisal Sheet for Academic Staff for Full Appraisal 2016

OLABISI ONABANJO UNIVERSITY AGO-IWOYE, NIGERIA FORMAT B CURRICULLUM VITAE AND ANNUAL APPRAISAL SHEET FOR ACADEMIC STAFF FOR FULL APPRAISAL 2016 PART 1: PERSONAL DATA 1. Name: Johnson Olarinde OLADESU 2. Department: Fine and Applied Arts 3. College/Faculty: College of Engineering / Faculty of Environmental Studies, Ibogun Campus 4. Date and Place of Birth: 14th February 1964, Oyan in Osun State 5. Nationality: Nigerian 6. Marital Status: Married 7. No of Children: Two (2) 8. Name & Address of Spouse: Mrs. Oladesu Kehinde.O. No1A Oko Osi Street, Sango Ota, OgunState. 9. Name & Address of Next of Kin: Mrs. Oladesu Kehinde.O.No1A Oko Osi Street, Sango Ota, Ogun State. 10. Date of First Appointment: 8th January 2004 11 Status of 1st Appointment & Salary: As Assistant Lecturer UASS 2/1 12. Present Position and Salary: Lecturer I / CONUASS 5/1 13. Date of Last Promotion: 1st October 2013 14. Date of Confirmation of Appointment: 28th June 2011 15. If not Confirmed, Why? Nil 16. Period of Present Contract: Nil 17. Total Number years of teaching and Research: (a) Polytechnic/College of Education Nil (b) University: 13 years 18. Email: [email protected] 1 B. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND 1. Academic Qualifications/ Institutions Attended (With Dates) PhD (Painting) Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 2016 MFA (Painting) Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 2000 B.A. Fine Arts (Second Class Upper Division) Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 1997 National Diploma (Upper Credit) The Polytechnic, Ibadan 1989 First Leaving Certificate Saint Charles Gram. Sch. Osogbo. 1996 Middle Sch. Leaving Certificate New Edubiase, Ghana Local Authority 1980 Primary Sch.