Standards, Health and Genetics in Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rassenliste Hund DE.Xlsx

Rasse Rassegruppe Affenpinscher 1 Afghanischer Windhund 1 Basenji 1 Bologneser 1 Chihuahua 1 Coton de Tuléar 1 Deutscher Spitz 1 Deutscher Pinscher 1 English Toy Terrier 1 Bretonischer Vorstehhund 1 Katalanischer Schäferhund 1 Havaneser 1 Hollandse Smoushond 1 Irish Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier 1 Italienisches Windspiel 1 Japan Chin 1 Papillon 1 Phalène 1 Kooikerhondje 1 Laika 1 Lakeland Terrier 1 Löwchen 1 Magyar Agár 1 Mastín del Pirineo 1 Russischer Toy 1 Siberian Husky 1 Toy‐Pudel 1 Italienischer Volpino 1 Aidi 2 Amerikanischer Cocker Spaniel 2 Anglo‐Français de petite vénerie 2 Australian Cattle Dog 2 Australian Kelpie 2 Australian Terrier 2 Bolonka Zwetna 2 Beagle 2 Beagle‐Harrier 2 Bearded Collie 2 Bedlington Terrier 2 Bergamasker Hirtenhund 2 Pyrenäenschäferhund 2 Border Collie 2 Border Terrier 2 Stichelhaariger Bosnischer Laufhund 2 Boston Terrier 2 Brandlbracke 2 Braque du Bourbonnais 2 Broholmer 2 Ca de Bestiar 2 Ca de Bou 2 Cairn Terrier 2 Cão da Serra de Aires 2 Ceský fousek 2 Chinesischer Schopfhund 2 Dackel 2 Dansk‐Svensk Gårdshund 2 Deutsche Bracke 2 Deutscher Jagdterrier 2 Deutscher Wachtelhund 2 Drever 2 English Cocker Spaniel 2 English Springer Spaniel 2 Ungarische Bracke 2 Finnischer Spitz 2 Foxterrier 2 Grand Basset Griffon Vendéen 2 Franz. Rauhaariger Vorstehhund 2 Belgischer Griffon 2 Grönlandhund 2 Irish Terrier 2 Islandhund 2 Jack Russell Terrier 2 Japan Spitz 2 Kanaanhund 2 Kerry Blue Terrier 2 Kleiner Münsterländer 2 Kromfohrländer 2 Kuvasz 2 Lagotto Romagnolo 2 Lappländischer Rentierhund 2 Lhasa Apso 2 Malteser -

2012 Annual Report 4 Fédération Cynologique Internationale TABLE of CONTENTS

2012 Annual report 4 Fédération Cynologique Internationale TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of conTenTs I. Message from the President 4 II. Mission Statement 6 III. The General Committee 8 IV. FCI staff 10 V. Executive Director’s report 11 VI. Outstanding Conformation Dogs of the Year 16 VII. Our commissions 19 VIII. FCI Financial report 44 IX. Figures and charts 50 X. 2013 events 59 XI. List of members 67 XII. List of clubs with an FCI contract 75 2012 Annual report 5 MessagE From ThE PrESident Chapter I Message froM The PresidenT be expected on this occasion. Although the World Dog Shows normally take place over four days, the Austrians ventured to hold the event over just 3 days. This meant a considerable increase in the daily number of competitors, which resulted in various difficulties. Experts had reckoned with more than 20,000 dogs taking part in the WDS 2012, so there was some surprise and disappointment when, with a figure of 18,608 dogs, this magic number was not reached. Looking at the causes, it is evident that the shortfall was mainly among those breeds that are still predominantly docked/ cropped in Eastern Europe, but were not admitted in Salzburg. The Austrian Kennel Club succeeded in organising and running this big event with flying colours and without any major hitches. The club and all the officials involved deserve our thanks and recognition for this performance. In appreciation of this and on behalf of the entire team, Dr Michael Kreiner, President of the Austrian Kennel Club, and Ms Margrit Brenner, the WDS Director, were awarded a badge of honour by the FCI. -

ALL-BREED DOGSHOW 07.09.2019 Luige Baas, Harjumaa

ALL-BREED DOGSHOW 07.09.2019 Luige baas, Harjumaa ENTRIES: Using EKL online system: https://online.kennelliit.ee/foreign.php (payment by card at the time of entering only, do not make a separate bank payment transfer). To be sent by e-mail: [email protected]. Please send the filled entry form, copy of dogs pedigree and champion/working diplomas (pedigree and champion diploma not necessary for dogs in FI/FIN/ER-registry) and payment copy and. ONLY entries sent to [email protected] will be accepted! Please transfer the entry fees to: Receiver: Põhja-Eesti Koertekasvatajate Klubi, IBAN: EE341010052031990004, SWIFT/BIC: EEUHEE2X. Please write breed and studbook numbers as payment explanation. ENTRY FEES: until 22.07.19 until 19.08.19 from 20.08.19* Baby, puppy, 24 € 39 € veteran Other classes 33 € 43 € 56 € Breeder & 8 € 13 € Progeny Class Brace Competition 13 € 25 € Child & Dog, Junior 13 € 25 € Handler Discount for entries made through EKL Online at https://online.kennelliit.ee/foreign.php (payment by card at the time of entering only) -3€ from the prices mentioned above. Veterans over 10 years free of charge. * Entries during Special Week are only accepted with prior arrangement with club, until it is possible to add dogs to the catalogue. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: entries and inquiries regarding entries: [email protected] for merchants & sales place reservations: [email protected] by phone: +372 517 5958 JUDGES: Group 1. Group 5. All Breeds – Dina Korna, Estonia Alaskan Malamute, Yakutian Laika, Nenets Herding Group 2. Laika, Chukotka Sled Dog, Samoyed, Siberian -

Catalogue 2020/21

LABORATORY FOR CLINICAL DIAGNOSTICS Catalogue 2020/21 SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE Serologie · EndokrinologieSerology · Endocrinology · Mikrobiologie · Microbiology · Pathologie · Pathology · Allergiediagnostik · Allergy · PCRs· PCR-Nachweise · Genetics · Hygiene· Genetik · Hygiene 2 Preface Dear colleagues, It‘s that time again: We have compiled a current price list for you. It is valid from July 2020 to June 2021. The laboratory: Our range of services includes The environment: We are aware of our responsibility everything from general diagnostics needed every – that is why we also try to commit ourselves in this day to specialised services. What all assays have field. An example: The Blue Angel on our shipping bags in common is: They get our full attention, they are is a sign that the bag has been recycled and will be carefully selected and validated for the specific animal recycled again. The laboratory itself is on the town’s species. They are accredited, which means that an list of fair trade companies, to name just a few of our external panel of specialists has approved the type of activities. analysis and the type of controls to which we subject ourselves on a daily basis. The people: We, the Laboklin team, are a group of very different people – many nations are represented, many professions, many different interests and areas of work. We are united by the desire to provide good analyses and to give you, in practice, the best possible support from the laboratory. This is why you will find us at many ͲW>ͲϭϯϭϴϲͲϬϭͲϬϬ professional training courses, why you will regularly find our new publications in the literature as well as new test offers. -

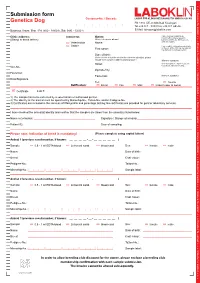

Genetics Dog Submission Form

+ Invoice to owner to owner + Invoice Submission form Customer-No. / Barcode LABOR FÜR KLINISCHE DIAGNOSTIK GMBH & CO. KG Genetics Dog PB 1810 DE-97668 Bad Kissingen Tel +49 971 72020 Fax +49 971 68546 Business Hours: Mon - Fri: 9:00 - 18:00 h, Sat: 9:00 - 13:00 h E-Mail: [email protected] Clinic address: Invoice to: Owner: I agree to allow my data to be transmitted to and processed by (Stamp or block letters) (Block letters only, please) Laboklin gmbH & Co. KG in order to Veterinarian Name: _________________________________________fulfill this contract. Owner I have read the information and details on the use of the data and my rights at First name:_________________________________________http://laboklin.com/dataprotection. Date of _birth:________________________________________ (If the invoice should be sent to the owner or submitter, please_________________________________________ include their complete address and signature ) (Owners signature) Street: _________________________________________With my signature, I agree to pay the costs for the laboratory testing. VAT-No.: _________________________________________________ Zipcode/city:_________________________________________ Fax/email: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________ Fax/email:_________________________________________(Owners signature) Date/Signature:_______________________________________________________________ Tel.: _________________________________________ Courier Notification: Email Fax Mail Report copy to owner 8105 -

Veterinäramt

Veterinäramt Liste der Hunderassen nach Rassentyp Das Zürcher Hundegesetz vom 14. April 2008 (HuG) bedingt die Einordnung eines jeden Hundes zu einem Rassetyp. Grosse oder massige Hundetypen gehören zur Rassetypenliste I (§ 7HuG); Als Richtwert dienten dabei die Grösse (mindestens 45 cm Stockmass) und das Gewicht (mindestens 16 kg Körpergewicht). Hundetypen mit erhöhtem Gefährdungspotential gehören zur Rassetypenliste II (§ 8 HuG). Die weiteren Hundetypen werden zur einfacheren Abgrenzung als ‚kleinwüchsig’ benannt (§ 4 Hundeverordnung vom 25. November 2009, HuV). Die Bezeichnung der einzelnen Rassetypen und die Rassebezeichnungen wurden durch die zentrale Hundedatenbank (ANIS AG), dem Bundesamt für Veterinärwesen und den kantonalen Vollzugsstellen gemeinsam erarbeitetet. Diese Liste findet auch bei der Registrierung von Hunden und bei Vorfällen mit Hunden gesamtschweizerisch Anwendung. Rassetyp Rassebezeichnung weitere Bezeichnungen Rassetypen- oder Varianten liste Schäferhunde Altdeutscher Schäferhund Typ I Altdeutscher Hütehund Schafpudel Typ I Australian Kelpie Typ I Australian Shepherd Typ I Bardino Perro de Ganado Majorero Typ I Bearded Collie Typ I Belgischer Schäferhund Groenendael, Laekenois, Mali- Typ I nois, Tervueren Bergamasker Typ I Berger de Beauce Beauceron Typ I Berger de Brie Typ I Berger de Picardie Typ I Berger de Savoie Typ I Berger des Pyrénées Typ I Border Collie Typ I Bulgarischer Hirtenhund Karakatschan Typ I Ca de Bestiar Mallorca-Schäferhund, Perro de Typ I pastor mallorquín Cao da Serra de Aires Typ I Ceskoslovenský -

Versicherungsumfang Hundehalter-Haftpflicht

Versicherungsumfang Hundehalter-Haftpflicht Kurzübersicht des Deckungsumfangs:* classic comfort Versicherungssummen Personen-, Sach- und Vermögensschäden pauschal 10 Mio. € 20 Mio. € 1 Vorsorgeversicherung in Höhe der Versicherungssumme ● ● Erhöhung und Erweiterung gilt auch für versicherungspflichtige Hunde (nicht für gefährliche Hunde2) ● ● Versicherte Personen Versicherungsnehmer als Halter/Mithalter ● ● Mitversichert sind als Halter/Mithalter • Ehepartner, Lebenspartner nach Lebenspartnerschaftsgesetz ● ● • Lebensgefährten des Versicherungsnehmers in häuslicher Gemeinschaft ● ● • Familienangehörige in häuslicher Gemeinschaft ● ● • Sonstige Personen in häuslicher Gemeinschaft ● ● Tierhüter, soweit nicht gewerbsmäßig tätig ● ● Ansprüche der fremden Tierhüter gegen den Versicherungsnehmer ● ● Regressansprüche von Sozialversicherungsträgern, Sozialhilfeträgern, Arbeitgebern, privaten Versicherern ● ● Nachversicherungsschutz bei Tod des Versicherungsnehmers ● ● Versicherte Eigenschaften und Tätigkeiten Kein Leinen- oder Maulkorbzwang ● ● Hüter fremder Hunde (subsidiärer Versicherungsschutz) ● ● Ausübung von Hundesport (z. B. Agility, Dog Dance, Fly Ball, Hunde-Frisbee, Zughundesport) ● ● Teilnahme an Ausbildungslehrgängen, Prüfungen, Veranstaltungen wie Ausstellungen, Schauvorführungen etc. ● ● Teilnahme an Rennen (auch Schlittenhunderennen) ● ● Eigene Nutzung als Assistenzhund (Blindenführhund, Signalhund, Behindertenbegleithund) ● ● Verwendung der versicherten Hunde als Zugtiere bei privaten Fahrten sowie Besitz und Gebrauch von eigenen -

World Dog Show & German Winner Show 8. – 12

TOP PARTNER WORLD DOG SHOW & GERMAN WINNER SHOW 8. – 12. NOVEMBER 2017 at Leipziger Messe PREMIUM PARTNER MEDIAPARTNER 2 Welcome to the World Dog Show 2017 We are pleased that the FCI has given the VDH the honorable and ambitious task of hosting the World Dog Show 2017. The World Dog Show will take place in Leipzig from 9 to 12 November 2017 and be the seventh World Dog show held in Germany (1935, 1956, 1973, 1981, 1991, 2003 and 2017). The day before the World Dog Show, the VDH will hold the German Winner Show on 8 November 2017 in the same location and not in August as originally planned. The VDH is happy to stage the World Dog Show at one of the largest and most modern exhibition sites in Europe - the Leipzig Trade Fair. Leipzig lies in the heart of Europe and offers outstanding transport services with an excellent motorway network. Leipzig-Halle airport is just a few kilometres from the exhibition grounds and its own local railway station provides a direct connection to the Leipzig main railway station. As a city of culture, Leipzig is itself also a touristic highlight. Barely any other city boasts such a great tradition of music as Leipzig. Names such as Johann Sebastian Bach, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy or Richard Wagner are inextricably associated with Leipzig. In the historical city centre the unique arcades and trading courts, the modern shops and the railway station mall are a real treat for those wanting to shop or those who enjoy a wander around. Leipzig has become well established as a host venue for dog shows over the decades and enjoys an excellent reputation among exhibitors. -

Hunde in Hamburg

BÜRGERSCHAFT DER FREIEN UND HANSESTADT HAMBURG Drucksache 21/16067 21. Wahlperiode 12.02.19 Schriftliche Kleine Anfrage des Abgeordneten Dennis Thering (CDU) vom 04.02.19 und Antwort des Senats Betr.: Freie und Hundestadt Hamburg – Ist-Stand und Entwicklung (IV) Ich frage den Senat: 1. Wie viele registrierte Hunde gibt es aktuell in Hamburg? (Bitte zusätzlich nach Rassen und Bezirken aufschlüsseln.) Wie viele dieser Hunde sind hundesteuerpflichtig? Die Registrierung von Hunden begann 2006 mit der Einrichtung des Hunderegisters aufgrund des erlassenen Hamburger Hundegesetzes und wird seither fortgeschrie- ben. Die zuständige Behörde erhält demzufolge fortlaufend entsprechend aufbereitete Daten unter anderem mit der aktuellen Anzahl gemeldeter Hunde (vergleiche Anlage 1, Stand 17.01.2019). Viele Hundehalterinnen und Hundehalter versäumen jedoch beim Wegzug aus Ham- burg, bei der Abgabe oder dem Tod des Hundes, auch im Hunderegister eine Abmel- dung vorzunehmen, außerdem sind im Hunderegister diverse Hundehalter erfasst, die ihren Hund lediglich in Hamburg ausführen, jedoch hier mangels Hamburger Wohnsitz zur Hundesteuer nicht herangezogen werden können. Teilweise sind auch mehrere Hunde für lediglich einen Hundehalterinnen und Hundehalter registriert. Im Rahmen der Erhebung der Hundesteuer werden Steuerkonten für die Hundehalte- rinnen und -halter als maßgebliche Steuerpflichtige geführt. Die Anzahl der Hunde, für die Hundesteuer entrichtet wird, kann davon abweichen und wird statistisch nicht erfasst. Derzeit werden für 50 563 Hundehalter Steuerkonten geführt. 2. Wie hat sich die Zahl der in Hamburg registrierten Hunde seit 2011 ent- wickelt? Bitte nach Jahren aufschlüsseln, jeweils einen einheitlichen Stichtag wählen sowie für Hamburg gesamt und für die einzelnen Bezir- ke angeben. Die zuständige Behörde erhält seit 2013 zum Anfang eines jeden Jahres entspre- chende Daten aus dem Hunderegister für die jährliche Beißstatistik übersandt. -

ÖKV Richtertag November 2019 • FCI RICHTERVERZEICHNIS NEU

ÖKV Richtertag November 2019 • FCI RICHTERVERZEICHNIS NEU FCI Startseite • Auf „Richterverzeichnis“ klicken • Eingabe Nachname des Richters Nummer, Nachname, Vorname, zuständiger NHV, Diszplin, Status Bei österreichischen Richtern Bemerkung, dass eine Freigabe nötig ist. Neben dem Namen gibt es ein Symbol für ein Briefkuvert, anklicken, dann haben Sie drei Möglichkeiten: • Kontakt aufnehmen mit dem Richter • Kontaktaufnahme mit der zuständigen NHV • Kontakt aufnehmen mit Richter und NHV Telefonnummern und Adressen gibt es nicht mehr. Auf den Namen direkt klicken • Vom Richter gesprochene FCI Sprachen, • Zulassungen Internationaler/nationaler Allgemeinrichter, BIS Richter Einzelne FCI Gruppen angeführt Bei Gruppenrichtern werden die Einzelrassen nicht mehr angeführt Richter für Einzelrassen: Liste mit allen Rassen der Gruppe, Zutreffendes wird angehakt. Außerdem gibt es noch ein Feld für Suspendierungen Liste mit Rassen die von der FCI nicht offiziell anerkannt sind American Eskimo Dog, American Hairless Terrier, Anglo Russian Hound, Barbado da Terceira, Biewer Terrier, Bluetick Coonhound, Cao do Barrocal Algarvio, Cao de Grado Transmontano, Continental Bulldog, Danish Spitz, Deltari Ilier, Epagneul de Saint Usuge, Gotland Hound, Halleforsdog, Kritikos Lagonikos, Markiesje, Plott Hound, Podenco Andaluz, Quen T`Bani Shqipetar, Rat Terrier, Ratonero Bodeguero Andaluz, Russian Hound, Russian Spotted Hound, Russian Tsvetnaya Bolanka, Silken Windsprite, Swedish White Elkhound, Taigan, Tenterfield Terrier, Toy Fox Terrier, Treeing Walker Coonhound, Working Kelpie Rassen sind bei österreichischen Gruppenrichtern und Allgemeinrichtern teilweise angehakt, teilweise nicht. Welche Arten von Rassen haben wir? Von der FCI endgültig anerkannte Rassen Im Moment 349 verschiedene Rassen FCI Rassennomenklatur nach Gruppen geordnet. • Können das CACIB erhalten und sind auch berechtigt die FCI Titel Weltsieger, Sektionssieger – Europa, Asien und Pazifik, Nord- und Südamerika und die Karibik – zu erhalten. -

Auswertung Zur Online-Umfrage Über Das Aktuelle Meinungsbild Zum Thema „Sogenannte Kampfhunde“ (SOKA) Allgemeine Infos Zur Umfrage

Auswertung zur Online-Umfrage über das aktuelle Meinungsbild zum Thema „sogenannte Kampfhunde“ (SOKA) Allgemeine Infos zur Umfrage Teilgenommen haben insgesamt 2.196 Personen, davon waren 1.987 Fragebögen auswertbar. Die Umfrage spiegelt lediglich die subjektive Meinung der Teilnehmer wieder, die durchaus auch von den tatsächlichen Begebenheiten abweichen kann. SOKA ist die Abkürzung für „sogenannter Kampfhund“ Geschlecht der teilnehmenden Personen männlich (17,71%) weiblich (81,03 %) keine Angabe (1,26%) Alter der teilnehmenden Personen 16 - 20 (2,97%) 21 - 30 (33,47%) 31 - 40 (29,94%) 41 - 50 (21,74%) 51 - 60 (10,72%) über 60 (1,16%) Schulabschluss keinen Abschluss (1,3%) Hauptschulabschluss (9,01%) Mittlere Reife (20,53%) Fachabi(9,22%) Abi (12,43%) Abgeschlossene Lehre (33,72%) Studium (12,43%) keine Angabe (1,36%) Sind Sie Hundehalter? 10% ja nein 90% Hatten Sie jemals persönlich Kontakt zu SOKAs? Ich bin Halter eines SOKAs 7% 15% 41% Ich habe regelmäßigen Kontakt 37% Ich habe selten Kontakt ich kenne SOKAs nur aus den Medien oder vom Sehen Welche Rassen besitzen die an der Umfrage teilnehmenden Hundehalter? (Mixe sind unter der jeweiligen Rasse mit eingeschlossen) Staffordshire Bullterrier 1,94 % Sonstige Rassen 22,21 % Rottweiler 3,59 % Retriever 5,9 % Pitbull 7,1 % Miniatur Bullterrier 4,52 % Mastino 2,03 % Jack Russell 1,29 % Franz. Bulldogge 0,14 % DSH 4,7 % Dogo Canario 0,65 % Dogo Argentino 0,74 % Dobermann 1,29 % Deutsche Dogge 1,94 % Dalmatiner 0,74 % Chihuahua 0,28 % Cane Corso 0,83 % Bullterrier 3,96% Bullmastiff 0,09 % Boxer 2,69 % Border Collie 2,21 % Bordeaux Dogge 0,65 % Australian Shepherd/Cattle Dog/ Kelpie 1,84 % Auslandshunde 2,4 % American Staffordshire Terrier 20,46 % Am./Engl./Continental Bulldog 5,81 % Die x-Achse beschreibt die Anzahl der Hunde. -

Veterinäramt Zollstrasse 20, 8090 Zürich Telefon 043 259 41 41, Fax

Veterinäramt Zollstrasse 20, 8090 Zürich Kanton Zürich Telefon 043 259 41 41, Fax 043 259 41 40, [email protected], www.veta.zh.ch Gesundheitsdirektion Ausgabedatum 18.03.2019 1/9 Liste der Hunderassen – alphabetisch geordnet Das Zürcher Hundegesetz vom 14. April 2008 (HuG) bedingt die Einordnung eines jeden Hundes zu einem Rassetyp. Grosse oder massige Hundetypen gehören zur Rassetypenliste I (§ 7HuG). Grundsätzlich zählen alle Hunde zur Rassetypenliste I, die nicht der Rassetypenliste II (verbotene Hunde) zuzuordnen sind und nicht von Elterntieren abstammen, die beide zu einer der im Anhang der Hundeverordnung genannten oder ähnlich kleinwüchsigen Rasse gehören (§ 4 Absatz 1 Hundeverordnung vom 25. November 2009, HuV). Als Richtwert zur Einteilung des Rassetyps dienten dabei die Grösse (mindestens 45 cm Stockmass) und das Gewicht (mindestens 16 kg Körpergewicht). Hundetypen mit erhöhtem Gefährdungspotential gehören zur Rassetypenliste II (§ 8 HuG). Die weiteren Hundetypen werden zur einfacheren Abgrenzung als ‚kleinwüchsig’ benannt. Die Bezeichnung der einzelnen Rassetypen und die Rassebezeichnungen wurden durch die zentrale Hundedatenbank (ANIS AG), dem Bundesamt für Veterinärwesen und den kantonalen Vollzugsstellen gemeinsam erarbeitetet. Diese Liste findet auch bei der Registrierung von Hunden und bei Vorfällen mit Hunden gesamtschweizerisch Anwendung. Rassenbezeichnung Weitere Bezeichnungen Rassentyp Rassentypen- oder Varianten liste Affenpinscher Pinscher und Schnauzer kleinwüchsig Afghanischer Windhund Windhunde Typ I Afghanischer