ECFG-Qatar-Feb-19.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

A Case Study of Arabic Heritage Learners and Their Community

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) “SPEAK AMERICAN!” OR LANGUAGE, POWER AND EDUCATION IN DEARBORN, MICHIGAN: A CASE STUDY OF ARABIC HERITAGE LEARNERS AND THEIR COMMUNITY BY KENNETH KAHTAN AYOUBY Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Education, the University of Port Elizabeth, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor Educationis Promoter: Prof. Susan van Rensburg, Ph.D. The University of Port Elizabeth November 2004 ABSTRACT This study examines the history and development of the “Arabic as a foreign language” (AFL) programme in Dearborn Public Schools (in Michigan, the United States) in its socio-cultural and political context. More specifically, this study examines the significance of Arabic to the Arab immigrant and ethnic community in Dearborn in particular, but with reference to meanings generated and associated to Arabic by non- Arabs in the same locale. Although this study addresses questions similar to research conducted on Arab Americans in light of anthropological and sociological theoretical constructs, it is, however, unique in examining education and Arabic pedagogy in Dearborn from an Arab American studies and an educational multi-cultural perspective, predicated on/and drawing from Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism, Paulo Freire’s ideas about education, and Henry Giroux’s concern with critical pedagogy. In the American mindscape, the "East" has been the theatre of the exotic, the setting of the Other from colonial times to the present. The Arab and Muslim East have been constructed to represent an opposite of American culture, values and life. -

Dukhan English School, Qatar

APPLICATION PACK FOR THE POST OF HEAD OF SCHOOL – SECONDARY Dukhan English School, Qatar Co-educational • 3 to 18 Years • 1300 pupils Required for August 2020 www.des.com.qa APPLICATION PACK FOR THE POST OF HEAD OF SCHOOL – SECONDARY Dukhan English School, Qatar Background - Dukhan English School Qatar Petroleum manages two schools in the Middle The new primary school opened in October 2018 and East - Mesaieed International School and Dukhan provides a well-equipped, state of the art, spacious English School. Both schools are non-selective and learning environment that has been hugely well- provide a quality educational opportunity for the received by both the school and the community. children of the employees of Qatar Petroleum. The secondary school, which is itself currently undergoing Qatar Petroleum owns Dukhan English School an exciting phase of reconstruction, will open in (DES), which is situated on the west coast of Qatar, October 2020. Dukhan English School accommodates a vibrant and multicultural school operating to serve 1300 students aged 3-18 across the soon to be the needs of the employees of Qatar Petroleum. It is completed, state-of-the-art single campus. As such, one of the oldest English medium schools in Qatar, the school promises first rate facilities that support the and traces its origins back to the early 1950s when delivery of a world class international education. British Petroleum, the operators of the Dukhan Field at that time, established a school in the building which Our vision is for our students to be high was later the Dukhan Water Sports clubhouse. -

Food Safety Lab Opens at Hamad Port

FRIDAY MARCH 19, 2021 SHABAN 6, 1442 VOL.14 NO. 5210 QR 2 Fajr: 4:24 am Dhuhr: 11:42 am FINE Asr: 3:08 pm Maghrib: 5:45 pm HIGH : 37°C LOW : 27 °C Isha: 7:15 pm World 5 Business 6 Sports 9 EU regulator deems Qatar a global reference Off He Goes battles hard AstraZeneca vaccine safe after point in commercial for Late Yousef Al Romaihi blood clot reports use of 5G: Yang Cup triumph Amir condoles with acting Tanzanian prez Food Safety Lab opens at Hamad Port HIS Highness the Amir of State of Qatar Sheikh Tamim Lab will speed up clearance procedures of food shipments bin Hamad Al Thani sent a cable of condolences to Acting Lab includes 10 test centres and a store of chemicals President of the United Repub- lic of Tanzania Samia Hassan QNA safety of results, in a way that Port’s accomplishments. The Suluhu on the death of Presi- DOHA contributes to ensuring qual- lab will complement efforts dent John Magufuli. (QNA) ity and safety of food in local to accelerate the process for MINISTER of Public Health market. food import companies in Qa- HE Dr Hanan Mohamed Al She said opening labs tar and protect the interests Kuwari and Minister of Trans- at the main port facilitates of traders and importers, in QU ranks 26th port and Communications clearance procedures of food addition to enhancing the re- HE Jassim bin Saif Al Sulaiti shipments. The minister indi- quirements of shipping opera- globally in THE inaugurated the Food Safety cated that the lab obtained in- tors, he added. -

English International Uranium Resources

International Atomic Energy Agency IUREP N.F.S. No. 125 November 1977 Distr. LIMITED Original: ENGLISH INTERNATIONAL URANIUM RESOURCES EVALUATION PROJECT IUREP NATIONAL FAVOURABILITY STUDIES BAHRAIN 77-10852 INTERNATIONAL URANIUM RESOURCES EVALUATION PROJECT I U R E P NATIONAL FAVOURABILITY STUDIES IUREP N.F.S. Noo 125 CONTENTS SUMMARY PAGE A. INTRODUCTION AMD GENERAL GEOGRAPHY 1. B. GEOLOGY OP BAHRAIN IN RELATION TO POTENTIALLY FAVOURABLE URANIUM BEARING AREAS C. PAST EXPLORATION -••• D. URANIUM OCCURRENCES AMD RESOURCES 2" Eo PRESENT STATUS OF EXPLORATION 2° P. POTENTIAL FOR MEW DISCOVERIES 2° BIBLIOGRAPHY 2° FIGURES MAP OF ARABIAN PENINSULA S U M M A R Y Bahrain consists of limestone, sandstone and marl of Cretaceous and Tertiary ages„ The potential for discoveries of uranium is very limited and thus the jjJRejruI^tj.v.e. J?otential is placed in the category of less than 1 OOP _ t_onnes uranium. - 1 - A.ND •• Bahrain, an archipelago, named after the largest island in the Gulf of Bahrain, an inlet of the Persian gulf, lies between the Qatar peninsula and the Hasa coast of Saudi Arabia. Bahrain Island extends 27 mi. north to south by 10 mi. east to west and is a low, generally level expanse of sand and bare rock, with Jebel Dukhan (450 ft) the highest of a cluster of small rocky hills in the centre. .Total land area is about 256 square miles or 662 square kilometres. Muharraq to the north and Sitra to the east are low-lying and are connected by causeway to the main island. Other islands are Umm An Naeaan Jidda and the Hawar group off Qatar, The climate is hot and rather humid in summer, but pleasant during the short winter season. -

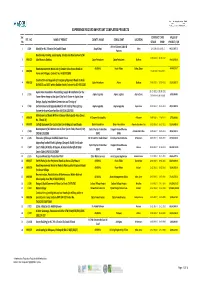

Experience Record Important Completed Projects

EXPERIENCE RECORD IMPORTANT COMPLETED PROJECTS Ser. CONTRACT DATE VALUE OF REF . NO . NAME OF PROJECT CLIENT'S NAME CONSULTANT LOCATION No STRART FINISH PROJECT / QR Artline & James Cubitt & 1 J/149 Masjid for H.E. Ghanim Bin Saad Al Saad Awqaf Dept. Dafna 12‐10‐2011/31‐10‐2012 68,527,487.70 Partners Road works, Parking, Landscaping, Shades and Development of Al‐ 22‐08‐2010 / 21‐06‐2012 2 MRJ/622 Jabel Area in Dukhan. Qatar Petroleum Qatar Petroleum Dukhan 14,428,932.00 Road Improvement Works out of Greater Doha Access Roads to ASHGHAL Road Affairs Doha, Qatar 48,045,328.17 3 MRJ/082 15‐06‐2010 / 13‐06‐2012 Farms and Villages, Contract No. IA 09/10 C89G Construction and Upgrade of Emergency/Approach Roads to Arab 4 MRJ/619 Qatar Petroleum Atkins Dukhan 27‐06‐2010 / 10‐07‐2012 23,583,833.70 D,FNGLCS and JDGS within Dukhan Fields,Contract No.GC‐09112200 Aspire Zone Foundation Dismantling, Supply & Installation for the 01‐01‐2011 / 30‐06‐2011 5 J / 151 Aspire Logistics Aspire Logistics Aspire Zone 6,550,000.00 Tower Flame Image at the Sport City Torch Tower in Aspire Zone Extension to be issued Design, Supply, Installation.Commission and Testing of 6 J / 155 Enchancement and Upgrade Work for the Field of Play Lighting Aspire Logestics Aspire Logestics Aspire Zone 01‐07‐2011 / 25‐11‐2011 28,832,000.00 System for Aspire Zone Facilities (AF/C/AL 1267/10) Maintenance of Roads Within Al Daayen Municipality Area (Zones 7 MRJ/078 Al Daayen Municipality Al Daayen 19‐08‐2009 / 11‐04‐2011 3,799,000.00 No. -

Hawar Island Protected Area

HAWAR ISLANDS PROTECTED AREA (KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN) M A N A G E M E N T P L A N Nicolas J. Pilcher Ronald C. Phillips Simon Aspinall Ismail Al-Madany Howard King Peter Hellyer Mark Beech Clare Gillespie Sarah Wood Henning Schwarze Mubarak Al Dosary Isa Al Farraj Ahmed Khalifa Benno Böer First Draft, January 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The development of comprehensive management plans is rarely the task of a single individual or even a small team of experts. Our knowledge and understanding of what the Hawar Islands represent comes after many years of painstaking effort by a number of scientists, local enthusiasts, and importantly, the leaders of the Kingdom of Bahrain. In this light we would like to thank the King of Bahrain, H.M. Shaikh Hamad Bin Isa Al Khalifa, for his vision and interest in ensuring the protection of the Hawar Islands. We would also like to extend our appreciation to Crown Prince and Commander of the Bahrain Defense Force H.H. Sheikh Salman Bin Hamad Al Khalifa for his support of legislative efforts and the implementation of research and management studies on the islands, and to Shaikh Abdulla Bin Hamad Al Khalifa for his support and encouragement, in particular with regard to his recognition of the importance of the islands at a global level. For assistance on the Hawar Islands during the field work, we would like to thank the officers and staff of the Bahrain Defense Force Abdul Gahfar Mohamad, Yousuf Al Jalahma, Jassim Al Ghatam and Eid Al Khabi for excellent logistical support, the management and staff of the Hawar Islands Resort, and the crews of the Coast Guard vessels for their invaluable knowledge of the islands and their provision of logistical support. -

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012 Quality of Service REPORT Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 The purpose of the study is to evaluate and benchmark Quality Levels offered by Mobile Network Operators, Qtel and Vodafone, in the state of Qatar. The independent study was conducted with an objective End-user perspective by Directique and does not represent any views of ictQATAR. This study is the property of ictQATAR. Any effort to use this Study for any purpose is permitted only upon ictQATAR’s written consent. 2 Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 READER’S ADVICE ........................................................................................ 4 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 TEAM AND EQUIPMENT ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 VOICE SERVICE QUALITY TESTING ...................................................................... 6 2.3 SMS, MMS AND BBM MEASUREMENTS ............................................................ 14 2.4 DATA SERVICE TESTING ................................................................................... 16 2.5 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................... 23 3 INDUSTRY RESULTS AND INTERNATIONAL BENCHMARK ........................... 25 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Qatar Industrial Landscape 2.0: Resilient and Stronger Contents

Qatar Industrial Landscape 2.0: Resilient and Stronger Contents Foreword 2 Qatar Industrial Landscape 1.0 3 Blockade: A Blessing in Disguise 7 Outlook: Qatar Industrial Landscape 2.0 12 Qatar 2.0- Resilient and Stronger | 1 Foreword Venkat Krishnaswamy Partner, Head of Advisory at KPMG Qatar The discovery of oil in the 1940’s started Qatar’s“ industrial growth and economic development. At the turn of the 21st century, Qatar witnessed exponential growth and diversification supported by development of industrial and port infrastructure and increased focus on exports. Government’s swift responses to the regional blockade underpinned Qatar’s economic resilience which ensured stability in industrial sector exports, both in the oil and gas and non-oil, non-gas segments. A blessing in disguise, the blockade led to rapid development in Qatar’s agro- and food-based industries driven by initiatives by the government and the private sector. After mitigating the immediate impact of the blockade, the government developed the manufacturing sector strategy, comprising nine strategic enablers which are expected to help Qatar build on its resilience and emerge stronger. The ending of blockade and a multi-sector development pipeline augurs well for Qatar’s industrial sector. ” Qatar 2.0- Resilient and Stronger | 2 Qatar Industrial Landscape 1.0 The discovery of oil in the 1940’s jump started Qatar’s industrial growth and economic development In the early 20th century, Qatar’s economy was heavily reliant on fishing and pearl diving. It transformed significantly with the discovery of oil in 1940. This drove industrial development, with the opening of Mesaieed Industrial City and Mesaieed Port in 1949. -

The Mineral Industry of Qatar in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook QATAR [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior October 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Qatar By Loyd M. Trimmer III and Philip A. Szczesniak In 2016, Qatar’s real gross domestic product (GDP) increased nonhydrocarbon sector, which accounted for 50.5% of real GDP, by 2.2% compared with an increase of 3.6% in 2015. Qatar increased by 5.6% in 2016 owing to additional Government was a major producer of aluminum (primary), ammonia, crude investment spending (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting petroleum, direct-reduced iron (DRI), helium, natural gas, Countries, 2017, p. 20, 99; Qatar Central Bank, 2017, p. 13, 21, sulfur, and urea. Qatar was the world’s fourth-ranked producer 47; Qatar National Bank S.A.Q., 2017, p. 7). of natural gas, accounting for 5.1% of global output, and the leading exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), accounting Production for 30% of the world’s LNG exports. According to BP p.l.c., In 2016, significant increases in production included that the country’s proven natural gas reserves were estimated to be of gasoline and kerosene, which increased by 24% and 13%, 24.3 trillion cubic meters, making it the country with the third respectively, compared with that of 2015. In 2016, significant largest proven natural gas reserves in the world, or 13.0% of decreases in production included that of residual fuel oil, which the world’s total, and the second largest natural gas reserves in was reported to have decreased by 57% compared with that of the Middle East and North Africa, behind Iran. -

Baghdad, 10Th Century the Dress of a Non-Muslim Woman

Baghdad, 10th Century The Dress of a non-Muslim woman The Rise of Islam in Medieval Society and its Influence on Clothing In order to understand and create the clothing of a 10th century woman in an Islamic State, it is incredibly important to understand how the advent of Islam affected day to day dress in Arabic society. It did not in fact create a new style of clothing, but instead it modified the styles of dress that were popular in the 6th and 7th centuries, many of which were influenced by Hellenic and Persian dress. As the progression of Islamic moral sensibilities became more and more impressed upon society, so too did the desire to keep much of the clothing simple, functional and suitable to the environment. Within the Early Islamic era (570-632 C.E) piety and morality were strongly impressed. Adornment was thought to be too ostentatious and fine fabrics and textiles considered inappropriate for a follower of Islam. During this time, one very important and identifiable change to clothing was created. It was considered against Islam if your clothing trailed the ground or if the basic under garments were past the ankle in length. “The Prophet said (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him): “Isbaal (wearing one’s garment below the ankles) may apply to the izaar (lower garment), the shirt or the turban. Whoever allows any part of these to trail on the ground out of arrogance, Allaah will not look at him on the Day of Judgment”. (reported by Abu Dawud, no 4085, and al-Nisaa’I in al-Mujtabaa, Kitab (al-Zeenah,Baab Isbaal al-Izaar) These hadiths are small collections of reports and statements of what The Prophet Muhammad was observed to say were written by his closest echelon of courtiers. -

Annex 5: Information About Qatar

Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna & Flora Doha (Qatar) 13 – 25 March 2010, Information about Qatar Location Qatar is a peninsula located halfway down the west coast of the Arabian Gulf. Its territory comprises a number of islands including Halul, Sheraouh, Al-Ashat and others. Topographic features The terrain is flat and rocky with some low-rising limestone outcrops in Dukhan area in the west and Jabal Fiwairit in the north. It is characterized by a variety of geographical phenomena including many coves, inlets, depressions and surface rainwater-draining basins known as riyadh (the gardens), which are found mainly in the north and central part of the peninsula. These areas have the most fertile soil and are rich in vegetation. Land area The total land area of Qatar is approximately 11,521km². Population The population of Qatar amounts to 1,500,000 inhabitants (according to the initial results of the second stage of the 2009 population census). 83 % of inhabitants reside in Doha and its main suburb Al-Rayyan. Capital city Doha Official language Arabic is the official language in Qatar, and English is widely spoken. Religion Islam is the official religion of the country, and the Shariah (Islamic law) is a main source of its legislation. Climate The climate is characterized by a mild winter and a hot summer. Rainfall in the winter is slight, averaging some 80 millimetres a year. Temperatures range from 7° degrees centigrade in January to around 45° degrees at the height of summer.