From Writers and Readers to Participants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

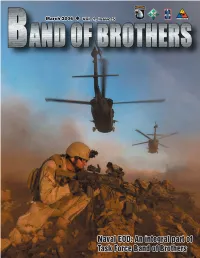

An Integral Part of Task Force Band of Brothers

March 2006 Vol. 1, Issue 5 Naval EOD: An integral part of Task Force Band of Brothers Two Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division sit on stage for a comedy skit with actress Karri Turner, most known for her role on the television series JAG, and comedians Kathy Griffin, star of reality show My Life on the D List and Michael McDonald, star of MAD TV. The three celebrities performed a number of improv skits for Soldiers and Airmen of Task Force Band of Brothers at Contingency Operating Base Speicher in Tikrit, Iraq, Mar. 17, as part of the Armed Forces Entertainment tour, “Firing at Will.” photo by Staff Sgt. Russell Lee Klika Inside... In every issue... Hope in the midst of disaster Page 5 Health and Fitness: Page 9 40 Ways to Eat Better Bastogne Soldiers cache in their tips Page 6-7 BOB on the FOB Page 20 Combat support hospital saves lives Page 8 Your new favorite cartoon! Aviation Soldiers keep perimeter safe Page 10 Hutch’s Top 10 Page 21 Fire Away! Page 11 On the cover... Detention facility goes above and beyond Page 12 Soldier writes about women’s history Page 13 U.S. Navy Explosive Or- Project Recreation: State adopts unit Page 16-17 dinance Disposal tech- nician Petty Officer 2nd Albanian Army units work with Page 18-19 Class Scott Harstead and Soldiers from the Coalition Forces in war on terrorism 1st Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Di- FARP guys keep helicopters in fight Page 22 vision dismount a UH- 60 Blackhawk from the Mechanics make patrols a success Page 23 101st Airborne Division during an Air Assault in the Ninevah Province, Soldier’s best friend Page 24 Iraq, Mar. -

Spring 2007 Newsletter

Dance Studio Art Create/Explore/InNovate DramaUCIArts Quarterly Spring 2007 Music The Art of Sound Design in UCI Drama he Drama Department’s new Drama Chair Robert Cohen empa- a professor at the beginning of the year, graduate program in sound sized the need for sound design initia- brings a bounty of experience with him. design is a major step in the tive in 2005 as a way to fill a gap in “Sound design is the art of provid- † The sound design program Tdepartment’s continuing evolution as the department’s curriculum. “Sound ing an aural narrative, soundscape, contributed to the success of Sunday in The Park With George. a premier institution for stagecraft. design—which refers to all audio reinforcement or musical score for generation, resonation, the performing arts—namely, but not performance and enhance- limited to, theater,” Hooker explains. ment during theatrical or “Unlike the recording engineer or film film production—has now sound editor, we create and control become an absolutely the audio from initial concept right vital component” of any down to the system it is heard on.” quality production. He spent seven years with Walt “Creating a sound Disney Imagineering, where he designed design program,” he con- sound projects for nine of its 11 theme tinued, “would propel UCI’s parks. His projects included Cinemagique, Drama program—and the an interactive film show starring actor collaborative activities of Martin Short at Walt Disney Studios its faculty—to the high- Paris; the Mermaid Lagoon, an area fea- est national distinction.” turing several water-themed attractions With the addition of at Tokyo Disney Sea; and holiday overlays Michael Hooker to the fac- for the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small ulty, the department is well World attractions at Tokyo Disneyland. -

Enjoy a Free Evening of Comedy in New York City's Central Park This

Enjoy a Free Evening of Comedy in New York City's Central Park This Summer! The Third Annual 'COMEDY CENTRAL Park' Live from SummerStage Starring Gabriel Iglesias with Special Guest Pablo Francisco Takes Place Rain or Shine on Friday, June 19 at 8:00 P.M. "COMEDY CENTRAL Park" Is One Of 31 Free Programs Offered During The 2009 Central Park SummerStage Season Through The City Parks Foundation In New York City The First 3,000 Attendees Will Receive A Complimentary, Reusable Shopping Bag Courtesy Of The Network's Pro-Social Initiative AddressTheMess NEW YORK, June 8 -- No two drink minimum necessary at this venue, it's entirely free. On Friday, June 19, New York City's Central Park turns into "COMEDY CENTRAL Park," a night of free stand-up comedy Live from SummerStage. The outdoor venue is located at mid-Central Park (near the Fifth Avenue & 72nd Street entrance) with doors opening at 7:00 p.m. and the show starting at 8:00 p.m. This is the third consecutive year COMEDY CENTRAL has participated in this hugely successful event. This year's presentation of "COMEDY CENTRAL Park" will feature comedian Gabriel Iglesias, who blends his impeccable voice skills with an uncanny knack for animated comedic storytelling that bring his issues to life, and special guest Pablo Francisco, who has an unbelievable ability to physically morph himself into movie stars, singers, friends, family, and a multitude of nationalities. Outback Steakhouse and All-Natural Snapple are the proud sponsors of "COMEDY CENTRAL Park." Iglesias's talent on stage has earned him several television appearances. -

The BG News April 2, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-2-1999 The BG News April 2, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 2, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6476. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. .The BG News mostly cloudy New program to assist disabled students Office of Disability Services offers computer program that writes what people say However, he said, "They work together," Cunningham transcripts of students' and ities, so they have an equal By IRENE SHARON (computer programs] are far less said. teachers' responses. This will chance of being successful. high: 69 SCOTT than perfect." Additionally, the Office of help deaf students to participate "We try to minimize the nega- The BG News Also, in the fall they will have Disability Services hopes to start in class actively, he said. tives and focus on similarities low: 50 The Office of Disability Ser- handbooks available for teachers an organization for disabled stu- Several disabled students rather than differences," he said. vices for Students is offering and faculty members, so they dents. expressed contentment over the When Petrisko, who has pro- additional services for the dis- can better accommodate dis- "We are willing to provide the services that the office of disabil- found to severe hearing loss, was abled community at the Univer- abled students. -

MOMMYBLOGS AS a FEMINIST ENDEAVOUR? by SUZETTE

MOMMYBLOGS AS A FEMINIST ENDEAVOUR? By SUZETTE BONDY-MEHRMANN Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Cathy Bray in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta October, 2011 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………….3 Introduction………………………………………………………………4 Defining my variables and situating myself in the research……………...4 What does it mean to espouse feminist principles online?.........................6 Method for studying mommyblogs……………………………………....7 Background and review of the literature………………………………....7 Analysis and discussion…………………………………………………14 Future directions………………………………………………………...17 Conclusion………………………………………………………………18 Works cited……………………………………………………………..20 Appendix 1: Study of Breastfeeding blogs by Suzette Bondy-Mehrmann ……………………………………………………...22 Appendix 2: Examples of Mommyblogs ………………………………35 Abstract It is important for feminist researchers to pay attention to new venues where women are creating and sharing knowledge. In the case of this paper we are looking at mothers online and the venue is the mamasphere, the virtual space where mothers are exchanging information through blogs. In interacting in this manner, however, are women engaging in a feminist endeavour? I approached this question through an interdisciplinary review of the research and writing available on mommyblogs against a backdrop of feminist theory of motherhood and by adding the findings from my own research on mommyblogs about breastfeeding. My findings indicate that -

BRIAN OWEN Line Producer

BRIAN OWEN Line Producer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS GUILTY PARTY Various Directors FUNNY OR DIE / PARAMOUNT + Season 1 – LA Insert Rebecca Addelman, Whitney Hodack Line Producer Location: Los Angeles DREAM CORP LLC Daniel Stessen ADULT SWIM Pilot, Seasons 1, 2, & 3 John Krasinski, Stephen Merchant Line Producer Mark Costa Location: Los Angeles THE GORBURGER SHOW Season 1 The Director Brothers 3 ARTS ENTERTAINMENT Line Producer FUNNY OR DIE / COMEDY CENTRAL Locations: Los Angeles TJ Miller, Josh Martin, Ryan McNeely MAYA & MARTY IN MANHATTAN Osmany Rodriquez NBC / BROADWAY VIDEO Series Lorne Michaels, Justus McLarty Segment Line Producer Location: Los Angeles LEGENDARY DUDAS Pilot & Season 1 Ben Pluimer NICKELODEON Line Producer Various Directors Sharla Sumpter Bridgett Location: Los Angeles Kevin Jakobowski CREATIVE LAB Various Directors NICKELODEON Line Producer Sharla Sumpter Bridgett Location: Los Angeles BETAS Season 1 Michael Lehmann AMAZON Production Supervisor Various Directors Michael London, Alan Cohen Locations: Los Angeles Alan Freedland, Michael Lehmann Scott Sites HOLE TO HOLE! Pilot Pam Brady ADULT SWIM Line Producer Pam Brady, Arden Myrin Location: Los Angeles FIGURE IT OUT Cycle 5 Dana Calderwood NICKELODEON Line Producer Magda Liolis, Eileen Braun Location: Los Angeles SKETCH SHOW Pilot Eric Dean Seaton NICKELODEON Line Producer Sharla Sumpter Bridgett, Laura House Location: Los Angeles CRASH & BERNSTEIN Pilot Bruce Leddy IT’S A LAUGH PRODUCTIONS Production Supervisor DISNEY XD Location: Los Angeles Eric Friedman, -

Analysis Article

FINDING READERS IN A CROWDED ROOM How multi-tasking Mom Bloggers attract audiences inside and outside the parent blogosphere Remember, the person you love is still in there, and they’d love to share their world with you. Be patient, and understand that the blogosphere they enter is entirely real, and actually does make them happier and more productive in the end. Though, bloggers don’t measure “productive” in quite the same way as the rest of the world does, i.e., get to starred posts in Google Reader, check TweetDeck for Mentions, commit to at least five #FF, submit to McSweeney’s. Again. -Alexandra Rosas, Good Day Regular People, from her post “When Someone You Love Has a Blog, Part 1” Alexandra Rosas published her three-part blog post, “When Someone You Love Has A Blog,” to explain to husbands and family members the peculiar habits of Mom Bloggers, a subset of online writers who have become famous, collectively, for engaging thousands of readers with their musings on motherhood and domesticity. Mom Bloggers like Ree Drummond, Heather Armstrong and Kelly Oxford have established lucrative 1 media careers after humble starts writing earnest personal stories for a tiny audience of friends and family. Rosas’ witty series hints at the methodical work, above and beyond writing, that Mom Bloggers do to attract a following. Close to four million women in North America identify as Mommy Bloggers, and about 14 percent of women in the United States read or contribute to these blogs, according to media consumer watchers Nielsen and Arbitron. Women often prefer this personal narrative style of journalism to traditional media. -

The BG News March 26, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-26-1999 The BG News March 26, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News March 26, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6471. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6471 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. fr&The BG News A daily independent student press Wday. March Sunny Gault, Chipps win USG elections in Bowling Green." By JEFF ARNETT The other presidential candi- The BG News dates expressed both disappoint- ment in the results and positive ugh: 49 Yesterday the Elections and feelings about the quality of the Opinions Board announced that election and the relatively high Clint Gault and Christy Chipps low: 24 voter turnout. There were about won this year's USG presidential 500 more votes than most recent' elections. elections, according to Carney. on The announcement was made "I'm very pleased with the by Elections and Opinions Board turnout," Kelley said. "I'm not chair Jeff Carney at 9 a.m. yester- bitter about anything. I think it day in the Prout Lounge Gault i Guest columnist Lance was a fine election." and Chipps received 961 votes, Cramner explains why Vice presidential candidate while Maryann Russell and Joe Iacobucci responded similar- broken promises have David All received 680, Bree ly about the quality of the elec- stopped him from Swatt and Joe Iacobucci received tion. -

Download Media

Heather B. Armstrong Heather B. Armstrong is a speaker, a best-selling and award-winning writer, a brand consultant, and a Trivial Pursuit answer. As a pioneer in the world of writing and Internet advertising, Heather built a massive audience of her own while helping global brands create meaningful, targeted content that reaches people in new, inventive ways. She’s also the mother of two daughters and can beat you at scrabble. Reach dooce® www.dooce.com 1,600,000-2,000,000 Heather’s personal website, dooce®, is widely Pageviews/month regarded as the most popular “mommy blog” in the world. The website has been actively 500,000-600,000 Sessions/month maintained since 2001 and was one of the first personal websites to sign with Federated 150,000-200,000 Media Publishing in 2005. Unique visitors/month dooce® Community 230,000-250,000 community.dooce.com Pageviews/month 61,000 As readership at dooce.com became Registered users increasingly active, a community of like-minded (and dierently-minded) people 50,000-60,000 Sessions/month began to form. The dooce® community was created in 2009 to provide a platform for 10,000-15,000 conversation, discussion, and support. Unique visitors/month Social @dooce TWITTER: 1.5+ million followers @dooce PINTEREST: 123k+ followers @dooce INSTAGRAM: 40k+ followers @dooce FACEBOOK: 16k+ subscribers Press and Features Various news outlets and publications have featured Heather for her work on dooce.com and elsewhere. In 2010, she was also invited to participate in The White House Forum on Workplace Flexibility. TELEVISION NEWS Oprah Nightline HLN The Today Show Dr. -

* TV-Filmresume-Letrhd

Glenn Berkovitz, CAS [email protected] 310- 902-1148 Production Sound Mixer Television programming: ANATOMY OF VIOLENCE (series pilot), 21st Century Fox Television/CBS - Dir.: Mark Pellington HOW TO LIVE WITH YOUR PARENTS (pilot + series), Fox Television/ABC - Prod: Claudia Lonow, Ken Ornstein, Mark Grossan THE SAINT (series pilot), Silver Screen Pictures - Dir.: Simon West BENT (series), NBC Universal Television/NBC - Prod.: Tad Quill, DJ Nash, Chris Plourde ZEKE & LUTHER (series - seasons 1, 2 & 3), Turtle Rock Pictures/Disney Channel - Prod.: Danielle Weinstock PARKS & RECREATION (series - pilot & season 1), NBC Television - Prod.: Morgan Sackett OCTOBER ROAD (series - season 2), Touchstone TV / ABC - Prod.: Scott Rosenberg, Mark Ovitz MEN OF A CERTAIN AGE (series pilot), Turner North / TNT Network - Dir.: Scott Winant COURTROOM K (series pilot), Fox Television - Dir.: Anthony & Joe Russo RAINES (series pilot), NBC Television/NBC - Dir.: Frank Darabont CAMPUS LADIES (series - 2 seasons), Principato/Young / Oxygen Network - Prod.: Paul Young, Brian Hall WEEDS (pilot + seasons 1 & 2), Lions Gate / Showtime Television - Exec. Prod.: Jenji Kohan, Mark Burley KAREN SISCO (series), Universal Television / ABC - Exec. Prod.: Bob Brush, Michael Dinner FOOTBALL WIVES (series pilot), Touchstone Television/ABC - Dir.: Bryan Singer HARRY GREEN AND EUGENE (series pilot), Paramount Pictures/ABC - Dir.: Simon West LUCKY (series), Castle Rock Television / F/X Networks - Exec. Prod.: Robb & Mark Cullen BOSTON LEGAL (assorted episodes), David E. Kelley Prod./Fox Television - Prod.: Bill D’Elia, Janet Knutsen CROSSING JORDAN (pilot + season 1), NBC Productions/NBC - Exec. Prod.: Tim Kring FREAKYLINKS (series), 20th Century Fox Television/Fox Broadcasting - Exec. Prod.: David Simkins M.Y.O.B. -

Montana Story Tour, the Story of Our Town

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Montana Story Tour, the story of Our Town| Developed and sponsored by the Montana Repertory Theatre Company, a professional equity theatre company in residence at the University of Montana-Missoula, Department of Drama/Dance Michael A. Johnson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Johnson, Michael A., "Montana Story Tour, the story of Our Town| Developed and sponsored by the Montana Repertory Theatre Company, a professional equity theatre company in residence at the University of Montana-Missoula, Department of Drama/Dance" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3014. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3014 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature/ Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only witfi the author’s explicit consent.