Crossing the North African and South African Ostrich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ostrich Production Systems Part I: a Review

11111111111,- 1SSN 0254-6019 Ostrich production systems Food and Agriculture Organization of 111160mmi the United Natiorp str. ro ucti s ct1rns Part A review by Dr M.M. ,,hanawany International Consultant Part II Case studies by Dr John Dingle FAO Visiting Scientist Food and , Agriculture Organization of the ' United , Nations Ot,i1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-21 ISBN 92-5-104300-0 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale dells Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1999 Contents PART I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE OSTRICH 5 Classification of the ostrich in the animal kingdom 5 Geographical distribution of ratites 8 Ostrich subspecies 10 The North -

Crossing the North African and South African Ostrich

CROSSING THE NORTH AFRICAN AND SOUTH AFRICAN OSTRICH. Bu J. E. DUERDEN, M.Sc., PH.D., Professor of Zoology, Rhodes University College, Grahamstown ; O~cer- in-Charge, Ostrich Investigations, Grootfontein School of Agriculture, Middelburg, C. P., South Africa. (With Plate VII, and Two Text-figures.) CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction 156 North African Os~,rlch . 157 South African Ostrich . 157 Nature of the Material 159 Dimensions 162 Colour 163 Northern Ostrich 165 Southern Ostrich 166 Cross-bred Ostriches 166 Bald Head-Patch . 168 The Egg 170 Egg of North African Ostrich 170 Egg of South African Ostrich 171 Eggs from Cross.matings 172 Eggs from Cross-bred Hens 175 The Wing Quills 174 North African Ostriches . 175 South African Ostriches . 176 Ci'oss-bred Ostriches 177 Survival of 42-plumed Ostriches 178 Scutellation of Middle Toe 181 Claw on Fourth Toe 185 Discusslon 186 Factorial Constitution 186 Adaptive Value of Changes 190 Establishment of Characters . !93 Specific distinctness of Northern and Southern Ostrich 196 Journ. of Gem WlI 11 156 Crossing the North and South African Ostrich ~[NTRODUCTION. TIIE continent of Africa, with the adjoining parts of Arabia, Palestine and Asia Minor, is the natural home of the ostrich genus Struthio. Beyond the confines of Aft'its however the wild bh'd is now extremely rare, if it exists a~ all i while in Africa it is slowly passing away as the continent becomes occupied by the white settler. The domesticated bird on the other hand has greatly increased in number during the fifty years of ostrich farming, amounting to near one million in 1913, though since considerably reduced owing to the less demand for plumage as a result of the prolonged war. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

2019 Annual Report OUR CEO’S STATEMENT TEAMWORK: the ESSENTIAL INGREDIENT

2019 Annual Report OUR CEO’S STATEMENT TEAMWORK: THE ESSENTIAL INGREDIENT I have known of the Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) since its founding in 2004, and All of the achievements described in this annual report can only have been accomplished through the dedication and its significant conservation successes achieved over the last 15-years; reintroducing hard-work of the SCF team members and government partners in the field. the scimitar-horned oryx and translocating West African giraffe. Taking the helm of SCF is a huge responsibility. The SCF teams in Chad and Niger include extremely competent field technicians who undertake arduous task of surveying and monitoring focal species. These team members are, in turn, supported by competent administrative and logistical staff. What I was unprepared for was realising just how far SCF, “punched above its weight.” Achieving these goals with a small, dedicated team in Paris and the field projects in Chad and Niger. And that the oryx and giraffe projects were not the full extent of the SCF’s activities. In partnership with many like-minded organizations and government authorities, SCF implements projects that improve protected area management, supporting endangered species, monitoring ecological systems, and provides medical assistance to communities in remote areas. The details of these activities are recorded in these pages. Over the last few months, I have come to admire the extent of SCF’s activities and the teams that lead these projects enormously. These achievements cannot be realised single-handedly. SCF benefits from a vast network of scientists and specialists that provide technical insight. It receives support from many quarters, without which we could not Implement these projects. -

Rattlesnake Roundups Killing Events Endanger Animals and the Environment

JANUARY 2017 A publication of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums Rattlesnake Roundups Killing Events Endanger Animals and the Environment ARE YOU ON TRACK? EDGE OF EXTINCTION BY THE NUMBERS Thoughtful Evaluation Leads to AZA Animal Programs are One Year of Field Conservation Conservation Course Corrections Conserving Wildlife and the in the Association of Zoos and Habitat on Which the Animals Rely Aquariums Community (2015) January 2017 Features 20 28 36 Rattlesnake Roundups - Are You on Track? Edge of Extinction Killing Events Endanger Thoughtful Evaluation Association of Zoos and Animals and the Leads to Conservation Aquariums Animal Programs Environment Course Corrections are conserving wildlife and the Rattlesnake roundups started Critical self-evaluation habitat on which the animals 50-60 years ago in states can be challenging and rely. Whether in Brazil, the like Texas and Oklahoma time-consuming. However, United States or elsewhere, and were advertised as a growing number of Species Survival Plan® events to help control snake Association of Zoos & programs and Taxon Advisory populations and protect Aquariums-accredited Groups can have a profound livestock and children. What facilities are relying on impact on the species on started as a niche event helpful tools like structured which they are focused. spread quickly, and states decision-making and the BY KATE SILVER including Alabama, Georgia Open Standards for the and Pennsylvania started Practice of Conservation to hosting their own roundups. monitor and measure their BY KATIE MORELL progress and evaluate the impact of their projects. BY MARY ELLEN COLLINS January 2017 | www.aza.org 1 9 11 13 Member View Departments 7 Collaboration 11 Species Survival 15 Capital Campaign 48 Faces & Places Chicago Zoological Society Plan® Highlight Texas State Aquarium and and U.S. -

Absence of Xenia in Ostrich Eggs

ABSENCE OF XENIA IN OSTRICH EGGS South African Ostrich Hens Mated with North African Ostrich Cocks Lay Eggs Characteristic of Their Own Species—No Signs of Male Influence on the Egg Shells—No Xenia J. E. DUERDEN, M.Sc, PH.D. Professor of Zoology, Rhodes University College, Grahamstown; Officer-in-charge, Ostrich Investigations, Grootfontein School of Agriculture, Middleburg, C.P. N THE JOURNAL OF HEREDITY for North African ostrich from Nigeria May, 1915, Vol. vi, No. 5, appears with the object of possibly improving I a review of certain investigations on the domesticated Cape strains, built xenia in fowls. By xenia is there up during the past fifty years of ostrich understood "that the eggs laid by farming from the original South African a hen are influenced as to size, shape, wild bird. The imported birds, origi- and color by the cock with which she nally captured by the Arabs from wild is mated." The occurrence of xenia nests, were stationed at the GrOot- in plants is first noted. Here cross- fontein School of Agriculture, and the pollination is often found to have an breeding experiments in connection with influence on the character of the seed them were placed in charge of the writer! obtained directly from the cross, a Zoologists generally recognize four result which is shown to be readily ex- species of the ostrich genus, 'Struthio: plained'from the peculiar formation of The North African ostrich, 5. camelus, the endosperm, where one of the two Linn.; the South African ostrich, 5. nuclei from the foreign pollen is involved australis, Gurney; the East African in its production. -

1. Introduction 86

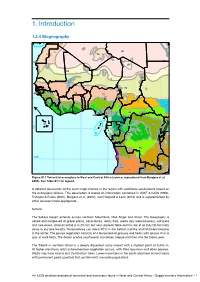

34 85 1. Introduction 86 69 30N 60 1.2.4 Biogeography87 88 93 65 95 98 96 92 97 94 111 99 62 61 35 100 101 115 36 25 70 2 39 83 102 37 38 59 71 1 4 3 4 6 7 5 10 40 44 116 9 103 104 31 12 11 13 16 0 73 41 8 18 14 45 15 17 66 20 47 72 27 43 48 46 42 19 118 112 10S 81 74 50 21 52 82 49 32 26 56 Figure S1.1 Terrestrial ecoregions in West and Central Africa (source: reproduced from Burgess et al. 75 2004). See Table S1.1 for legend. 106 51 119 33 55 64 53 67 63 84 A2 0detailedS description of the eight major biomes in the region with additional subdivisions based on76 29 the ecoregions follows. This description is based on information contained 5in8 WWF6 8& IUCN (1994), 30 Fishpool & Evans (2001), Burgess et al. (2004), and Happold & Lock (2013) and is supplemented57 by 114 other sources where appropriate. 107 54 Terrestrial ecoregions 105 109 113 Sahara Country boundary 22 77 78 The Sahara Desert extends across northern Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Chad. The topography11 7is 28 30S 79 varied and composed of gravel plains, sand dunes, rocky flats, wadis110 (dry watercourses), salt pans 108 23 and rare oases. Annual rainfall is 0–25 mm but very unpredictable and no rain at all may fall for many 0 250 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 80 years in any one locality. -

Ratites Are Now Consid- Ered to Be Derived from Unrelated Groups of Flighted Birds That Have Adapted to a Highly Specialized Ter- Restrial Lifestyle

atites are a group of large, ground-dwelling birds that share the common characteristic CHAPTER of flightlessness. The term ratite is derived R from the Latin ratitus, meaning raft, and refers to the shape of the sternum that lacks a keel. There is no scientific classification “ratite,” but the term is used to collectively describe the ostrich (from Africa), rhea (from South America), emu (from Aus- tralia), cassowary (from Australia and the New Guinea archipelago) and the kiwi (from New Zea- 48 land).1 Once considered to be a single category of related primitive birds, the ratites are now consid- ered to be derived from unrelated groups of flighted birds that have adapted to a highly specialized ter- restrial lifestyle. In the 1980’s, it was estimated that between 90,000 to 120,000 ostriches existed on approximately 400 ATITES farms as part of a multi-crop rotation system in R South Africa. During the same time period, a fledg- ling industry arose in the United States and by the end of the decade, it was estimated that there were close to 10,000 ostriches and about 3,000 emus in the US.55 This growing interest in breeding ostriches and emus has occurred due to the birds’ potential as producers of meat, feathers and skin. Ostrich skin is charac- James Stewart terized by prominent feather follicles and is a high status product of the leather industry. Ostriches yield a red meat that has the flavor and texture of beef, yet has the cholesterol and nutritional value of poultry. Ostrich feathers, still used for dusters, are also used in the manufacture of fashion and theatrical attire. -

Struthio Camelus Camelus Linnaeus, 1858) in the Koutous, Niger

Journal of Applied Life Sciences International 23(6): 1-14, 2020; Article no.JALSI.57849 ISSN: 2394-1103 Ethnozoological Knowledge and Local Perceptions about the Reintroduction of the North African Ostrich (Struthio camelus camelus Linnaeus, 1858) in the Koutous, Niger Maïmounatou Ibrahim Mamadou1,2*, Abdoulaye Harouna3, Maman Kamal Abdou Habou1, Marie Petretto4 and Ali Mahamane1,5 1Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université de Diffa, BP: 78, Diffa, Niger. 2Sahara Conservation Fund, BP: 981 Niamey, Niger. 3Noé, BP: 338 Niamey, Niger. 4Marwell Wildlife, Colden Common, Winchester, SO21 1JH, UK. 5Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université Abdou Moumouni, BP: 10662, Niamey, Niger. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author MIM the lead author of the article, developed the research protocol, collected field data and wrote the manuscript. Author AH gave methodological advice for carrying out this work and revised the manuscript. Author MKAH participated in the analyses of the manuscript. Authors MP and AM contributed in supervising the work and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/JALSI/2020/v23i630165 Editor(s): (1) Dr. J. Rodolfo Rendón Villalobos, National Polytechnic Institute, México. Reviewers: (1) Sugan Chand Meena, ICAR-Central Arid Zone Research Institute, India. (2) Akongte Peter Njukang, Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, University of Dschang, Cameroon. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/57849 Received 11 April 2020 Original Research Article Accepted 18 June 2020 Published 30 June 2020 ABSTRACT The North African Ostrich (Struthio camelus camelus), also known as the red-necked ostrich, disappeared from Niger 15 years ago but preliminary work completed in 2011 has shown that the species has not vanished from the collective memory in the Koutous. -

2016 Wildcare Institute Annual Report

WildCare Institute 2016 Annual Report WildCare At A Glance Center for American Burying Beetle Conservation Center for Conservation in Madagascar • Saving this important insect helps the ecosystem because this insect removes • Supporting the international consortium, Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group, dead and decaying animals naturally based at the Saint Louis Zoo—a founding member in 1988 • Reintroducing Zoo-born beetles to the wild—a first for an endangered • Conserving biodiversity through research, education and capacity building species in Missouri • Studying the health and genetics of endangered lemurs and endemic • Researching beetle genetics and breeding helps species recovery carnivore communities Center for Avian Conservation in the Pacific Islands Center for Native Pollinator Conservation • Working to save Pacific Island bird species since 1994 • Planting dozens of miles of pollinator habitats along roadsides with support from • Building assurance populations to prevent island birds from disappearing multiple Missouri state agencies • Transferring “seed” bird populations to neighboring snake-free sanctuary islands • Founding Missourians for Monarchs to develop a state-wide conservation plan for for successful breeding monarch butterflies and native pollinators • Continuing to establish populations in human care to support wild populations • Increasing monarch butterfly habitat by encouraging planting of multiple community pollinator gardens Center for Avian Health in the Galápagos Islands • Spearheading honey bee/pollinator -

Hannover 2016

University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover Department of Pathology Aimara Bello Casuistic evaluation of necropsied ratites (Struthioniformes) in northwestern Germany - a retrospective study - Hannover 2016 Attachment 4a: § 9 paragraph 1 of the Doctoral Regulations University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover Casuistic evaluation of necropsied ratites (Struthioniformes) in northwestern Germany - a retrospective study - INAUGURAL –DISSERTATION in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Veterinary Medicine -Doctor medicinae veterinariae – (Dr. med. vet.) Submitted by Aimara Bello Caracas, Venezuela Hannover 2016 Academic supervision: 1. Prof. Dr. med.vet. W. Baumgärtner. Department of Pathology TiHo 1. Referee: Prof. Dr. med.vet. W. Baumgärtner 2. Referee: Prof. Dr. med. vet. S. Rautenschlein Day of the oral examination: 31.10.2016 Results of the Doctoral Thesis were partially presented in the following events: Authors: A. Bello, S. Lapp, P. Wohlsein, W. Baumgärtner Title (German): Retrospektive Untersuchung der Erkrankungs- und Todesursachen von 66 Laufvögeln (Struthioniformes). Format: Oral presentation Event: 57. Jahrestagung der Fachgruppe Pathologie der Deutschen Veterinärmedizinischen Gesellschaft, 08. – 09.03.2014. Fulda, Germany. Published in: Tierärztliche Praxis G 42 (2014) S. A9 To my family “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.” ― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince Table of contents Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: -

Guard Dogs of Africa Plus: Kids Contest! Myzoo

MYZOO for members of Woodland Park Zoo • Summer 2014 MEET OUR FASTEST CATS: CHEETAHS GUARD DOGS OF AFRICA PLUS: KIDS CONTEST! MYZOO DEAR MEMBERS, As protecting nature grows increasingly challenging, people ask me where I find hope. My reply: the zoo is a place of hope. Every day I witness it in the wonder on children’s LETTER faces; in the perseverance with which passionate, highly trained experts care for animals FROM THE here and in wild places; and in the can-do attitude our educators create in schools. Your zoo is a hope-building enterprise. In addition to getting you up close to amazing PRESIDENT animals, we do scientific research on species’ health, social behavior and reproduction. And we connect millions of visitors to more than 35 inspiring conservation collaborators saving wild animals and helping to protect 1.25 million acres of habitat here and globally. Matt Hagan Without actions like these, many iconic species will go extinct in 15 to 50 years. Take Earth’s largest land mammal. A century ago, more than 5 million elephants roamed Africa, while some 200,000 did so across Asia. Today, as few as 400,000 and 25,000 remain, respectively. Each day, nearly 100 African elephants are killed illegally by poachers to fund organized crime. Ivory is now more valuable than gold, and China and the U.S. are its top markets. In Asia, illegal poaching is compounded by rapidly dwindling habitats as human numbers there soar. That’s why over the next five years, we will invest an additional $1.5 to $3 million to expand our elephant program and significantly improve the Elephant Forest exhibit.