Intraligamentous and Retroperitoneal Tumors of the Uterus and Its Adnexa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Morphology, Androgenic Function, Hyperplasia, and Tumors of the Human Ovarian Hilus Cells * William H

THE MORPHOLOGY, ANDROGENIC FUNCTION, HYPERPLASIA, AND TUMORS OF THE HUMAN OVARIAN HILUS CELLS * WILLIAM H. STERNBERG, M.D. (From the Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Tulane University of Louisiana and the Charity Hospital of Louisiana, New Orleans, La.) The hilus of the human ovary contains nests of cells morphologically identical with testicular Leydig cells, and which, in all probability, pro- duce androgens. Multiple sections through the ovarian hilus and meso- varium will reveal these small nests microscopically in at least 8o per cent of adult ovaries; probably in all adult ovaries if sufficient sections are made. Although they had been noted previously by a number of authors (Aichel,l Bucura,2 and von Winiwarter 3"4) who failed to recog- nize their significance, Berger,5-9 in 1922 and in subsequent years, pre- sented the first sound morphologic studies of the ovarian hilus cells. Nevertheless, there is comparatively little reference to these cells in the American medical literature, and they are not mentioned in stand- ard textbooks of histology, gynecologic pathology, nor in monographs on ovarian tumors (with the exception of Selye's recent "Atlas of Ovarian Tumors"10). The hilus cells are found in clusters along the length of the ovarian hilus and in the adjacent mesovarium. They are, almost without excep- tion, found in contiguity with the nonmyelinated nerves of the hilus, often in intimate relationship to the abundant vascular and lymphatic spaces in this area. Cytologically, a point for point correspondence with the testicular Leydig cells can be established in terms of nuclear and cyto- plasmic detail, lipids, lipochrome pigment, and crystalloids of Reinke. -

Female Adnexal Tumor of Probable Wolffian Origin, FATWO: Report of a Rare Case

J Cases Obstet Gynecol, 2016;3(1):15-18 Jo ur nal o f Ca se s in Ob st et ri cs &G ynec olog y Case Report Female adnexal tumor of probable wolffian origin, FATWO: Report of a rare case Cevdet Adiguzel1,*, Eylem Pinar Eser2, Sebnem Baysal1, Esra Selver Saygili Yilmaz1, Eralp Baser1 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Adana, Turkey 2 Department of Pathology, Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Adana, Turkey Abstract Female adnexal tumors of probable Wolffian origin (FATWO) arise in the broad ligament from the remnants of the me- sonephric duct. The behavior of these tumors is generally benign. However, they can also behave aggressive- ly and exhibit recurrences or metastases. Herein we present a rare case of FATWO that was diagnosed in a premenopausal woman. Key words: Adnexal mass, FATWO, wolffian Introduction Case presentation Female adnexal tumors of probable Wolffian origin (FAT- A 42-year-old pre-menopausal woman, gravida 2, para 2, WO) were first documented in 1973 by Kariminejad and was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a left adnexal Scully [1]. These tumors arise in the broad ligament from mass suspected to be malignant. Her previous gynecolog- the remnants of the mesonephric duct such as epoophoron, ical history included a cesarean section for dystocia. Pel- paroophoron and Gartner’s duct [2]. Approximately 80 cas- vic ultrasound showed a normal sized uterus, with a thin es of FATWO have been previously reported in the litera- and regular endometrial lining. The right ovary was nor- ture [3]. -

A Contribution to the Morphology of the Human Urino-Genital Tract

APPENDIX. A CONTRIBUTION TO THE MORPHOLOGY OF THE HUMAN URINOGENITAL TRACT. By D. Berry Hart, M.D., F.R.C.P. Edin., etc., Lecturer on Midwifery and Diseases of Women, School of the Royal Colleges, Edinburgh, etc. Ilead before the Society on various occasions. In two previous communications I discussed the questions of the origin of the hymen and vagina. I there attempted to show that the lower ends of the Wolffian ducts enter into the formation of the former, and that the latter was Miillerian in origin only in its upper two-thirds, the lower third being formed by blended urinogenital sinus and Wolffian ducts. In following this line of inquiry more deeply, it resolved itself into a much wider question?viz., the morphology of the human urinogenital tract, and this has occupied much of my spare time for the last five years. It soon became evident that what one required to investigate was really the early history and ultimate fate of the Wolffian body and its duct, as well as that of the Miillerian duct, and this led one back to the fundamental facts of de- velopment in relation to bladder and bowel. The result of this investigation will therefore be considered under the following heads:? I. The Development of the Urinogenital Organs, Eectum, and External Genitals in the Human Fcetus up to the end of the First Month. The Development of the Permanent Kidney is not CONSIDERED. 260 MORPHOLOGY OF THE HUMAN URINOGENITAL TRACT, II. The Condition of these Organs at the 6th to 7th Week. III. -

Actinomycosis Israeli, 129, 352, 391 Types Of, 691 Addison's Disease, Premature Ovarian Failure In, 742

Index Abattoirs, tumor surveys on animals from, 823, Abruptio placentae, etiology of, 667 828 Abscess( es) Abdomen from endometritis, 249 ectopic pregnancy in, 6 5 1 in leiomyomata, 305 endometriosis of, 405 ovarian, 352, 387, 388-391 enlargement of, from intravenous tuboovarian, 347, 349, 360, 388-390 leiomyomatosis, 309 Acantholysis, of vulva, 26 Abdominal ostium, 6 Acatalasemia, prenatal diagnosis of, 714 Abortion, 691-697 Accessory ovary, 366 actinomycosis following, 129 Acetic acid, use in cervical colposcopy, 166-167 as choriocarcinoma precursor, 708 "Acetic acid test," in colposcopy, 167 criminal, 695 N-Aceryl-a-D-glucosamidase, in prenatal diagnosis, definition of, 691 718 of ectopic pregnancy, 650-653 Acid lipase, in prenatal diagnosis, 718 endometrial biopsy for, 246-247 Acid phosphatase in endometrial epithelium, 238, endometritis following, 250-252, 254 240 fetal abnormalities in, 655 in prenatal diagnosis, 716 habitual, 694-695 Acridine orange fluorescence test, for cervical from herpesvirus infections, 128 neoplasia, 168 of hydatidiform mole, 699-700 Acrochordon, of vulva, 31 induced, 695-697 Actinomycin D from leiomyomata, 300, 737 in therapy of missed, 695, 702 choriocarcinoma, 709 tissue studies of, 789-794 dysgerminomas, 53 7 monosomy X and, 433 endodermal sinus tumors, 545 after radiation for cervical cancer, 188 Actinomycosis, 25 spontaneous, 691-694 of cervix, 129, 130 pathologic ova in, 702 of endometrium, 257 preceding choriocarcinoma, 705 of fallopian tube, 352 tissue studies of, 789-794 of ovary, 390, 391 threatened, -

PATHOLOGY of FEMALE GENITALE SYSTEM What Is the Benefit of Knowing This System?

PATHOLOGY OF FEMALE GENITALE SYSTEM What is the benefit of knowing this system? It is certain that the detailed examination of these diseases and their knowledge will play an important role in the development of healthy animal populations. This success will also affect the economy. OVARIUM Developmental anomalies Agenesis of one or both ovaries is rare, but is observed in ruminants, swine, and dogs. In bilateral agenesis, the tubular genitalia may be absent as part of the defect or, if present, are infantile or underdeveloped. Ovarian remnants. Interest in the occurrence of anomalous ovarian duplication commonly arises when either cats or dogs, supposedly surgically neutered, exhibit signs of estrus. In the bitch, the effects of circulating estrogen are easily detected by serial vaginal cytology. Hormonal studies are confirmatory, and ultrasonographic and exploratory surgical examinations are also done. Duplication of ovarian tissues is very rare. Although there are no controlled studies, duplication may just be splitting of ovarian tissue. Hypoplasia of the ovaries is studied primarily in cattle, but occurs in other species. It is usually bilateral but varies considerably in its severity and symmetry so that “severe hypoplasia” or “partial hypoplasia” may be applicable to one or both ovaries. In severe hypoplasia, the defective gonad varies in size from a cordlike thickening in the cranial border of the mesovarium to a flat, smooth, firm, bean-shaped structure in the normal position. There are neither follicles nor luteal scars and, microscopically, the ovary is largely composed of medullary connective tissues and blood vessels. Ectopic adrenal tissue is usually found incidentally during histopathology. -

1- Development of Female Genital System

Development of female genital systems Reproductive block …………………………………………………………………. Objectives : ✓ Describe the development of gonads (indifferent& different stages) ✓ Describe the development of the female gonad (ovary). ✓ Describe the development of the internal genital organs (uterine tubes, uterus & vagina). ✓ Describe the development of the external genitalia. ✓ List the main congenital anomalies. Resources : ✓ 435 embryology (males & females) lectures. ✓ BRS embryology Book. ✓ The Developing Human Clinically Oriented Embryology book. Color Index: ✓ EXTRA ✓ Important ✓ Day, Week, Month Team leaders : Afnan AlMalki & Helmi M AlSwerki. Helpful video Focus on female genital system INTRODUCTION Sex Determination - Chromosomal and genetic sex is established at fertilization and depends upon the presence of Y or X chromosome of the sperm. - Development of female phenotype requires two X chromosomes. - The type of sex chromosomes complex established at fertilization determine the type of gonad differentiated from the indifferent gonad - The Y chromosome has testis determining factor (TDF) testis determining factor. One of the important result of fertilization is sex determination. - The primary female sexual differentiation is determined by the presence of the X chromosome , and the absence of Y chromosome and does not depend on hormonal effect. - The type of gonad determines the type of sexual differentiation in the Sexual Ducts and External Genitalia. - The Female reproductive system development comprises of : Gonad (Ovary) , Genital Ducts ( Both male and female embryo have two pair of genital ducts , They do not depend on ovaries or hormones ) and External genitalia. DEVELOPMENT OF THE GONADS (ovaries) - Is Derived From Three Sources (Male Slides) 1. Mesothelium 2. Mesenchyme 3. Primordial Germ cells (mesodermal epithelium ) lining underlying embryonic appear among the Endodermal the posterior abdominal wall connective tissue cell s in the wall of the yolk sac). -

Ta2, Part Iii

TERMINOLOGIA ANATOMICA Second Edition (2.06) International Anatomical Terminology FIPAT The Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology A programme of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA) TA2, PART III Contents: Systemata visceralia Visceral systems Caput V: Systema digestorium Chapter 5: Digestive system Caput VI: Systema respiratorium Chapter 6: Respiratory system Caput VII: Cavitas thoracis Chapter 7: Thoracic cavity Caput VIII: Systema urinarium Chapter 8: Urinary system Caput IX: Systemata genitalia Chapter 9: Genital systems Caput X: Cavitas abdominopelvica Chapter 10: Abdominopelvic cavity Bibliographic Reference Citation: FIPAT. Terminologia Anatomica. 2nd ed. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology, 2019 Published pending approval by the General Assembly at the next Congress of IFAA (2019) Creative Commons License: The publication of Terminologia Anatomica is under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0) license The individual terms in this terminology are within the public domain. Statements about terms being part of this international standard terminology should use the above bibliographic reference to cite this terminology. The unaltered PDF files of this terminology may be freely copied and distributed by users. IFAA member societies are authorized to publish translations of this terminology. Authors of other works that might be considered derivative should write to the Chair of FIPAT for permission to publish a derivative work. Caput V: SYSTEMA DIGESTORIUM Chapter 5: DIGESTIVE SYSTEM Latin term Latin synonym UK English US English English synonym Other 2772 Systemata visceralia Visceral systems Visceral systems Splanchnologia 2773 Systema digestorium Systema alimentarium Digestive system Digestive system Alimentary system Apparatus digestorius; Gastrointestinal system 2774 Stoma Ostium orale; Os Mouth Mouth 2775 Labia oris Lips Lips See Anatomia generalis (Ch. -

An Unusual Case of Anterior Vaginal Wall Cyst 1GS Anitha, 2M Prathiba, 3Mangala Gowri

JSAFOG An Unusual10.5005/jp-journals-10006-1367 Case of Anterior Vaginal Wall Cyst CasE REPORT An Unusual Case of Anterior Vaginal Wall Cyst 1GS Anitha, 2M Prathiba, 3Mangala Gowri ABSTRACT asymptomatic and have been reported to occur in as Vaginal cysts are rare and are mostly detected as an incidental many as 1% of all women. Because the ureteral bud also finding during a gynecological examination. Gartner duct cysts, develops from the Wolffian duct, it is not surprising that the most common benign cystic lesion of the vagina, represent Gartner duct cysts have been associated with ureteral embryologic remnants of the caudal end of the mesonephric and renal abnormalities, including congenital ipsilateral (Wolffian) duct. These cysts are usually small and asymptomatic and have been reported to occur in as many as 1% of all women. renal dysgenesis or agenesis, crossed fused renal ectopia A 17-year-old unmarried girl presented with mass per vagina and ectopic ureters. In addition, associated anomalies since one and a half year. On examination, anterior vaginal of the female genital tract, including structural uterine wall cyst of 8 × 4 × 3 cm was detected. Surgical excision anomalies (ipsilateral müllerian duct obstruction, bicor- of the cyst was done under spinal anesthesia by sharp and nuate uteri, and uterus didelphys) and diverticulosis of blunt dissection. The cyst was filled with mucoid material and histopathological examination confirmed Gartner origin. This the fallopian tubes, have been described. Gartner cysts is a rare case of large Gartner cyst. can be asymptomatic or can present with symptoms like Keywords: Anterior vaginal wall cyst, Gartner cyst, Müllerian mass per vagina, vaginal discharge, pain, dyspareunia, cyst, Surgical excision. -

Embryology /Organogenesis

Embryology /organogenesis/ Week 4: 06. 04 – 10. 04. 2009 Development and teratology of reproductive system. Repetition: blood and hematopoiesis. 19. Indifferent stage in development of reproductive system. 20. Development of male and female gonad. 21. An overview of development of male and female genital duct. 22. Development of external genital organs. 23. Developmental malformations of urogenital system. Male or female sex is determined by spermatozoon Y in the moment of fertilization SRY gene, on the short arm of the Y chromosome, initiates male sexual differentiation. • The SRY influences the undifferentiated gonad to form testes, which produce the hormones supporting development of male reproductive organs. • Developed testes produce testosterone (T) and anti- Mullerian hormone (AMH). • Testosterone stimulates the Wolffian ducts development (epididymis and deferent ducts). • AMH suppresses the Mullerian ducts development (fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper vagina). • Indifferent stage – until the 7th week • Different stage • Development of gonads • Development of reproductive passages • Development of external genitalia Development of gonads mesonephric ridge (laterally) Dorsal wall of body: urogenital ridge genital ridge (medially), consisting of mesenchyme and coelomic epithelium (Wolffian duct) gonad Three sources of gonad development: 1 – condensed mesenchyme of gonadal ridges (plica genitalis) 2 – coelomic epithelium (mesodermal origin) 3 – gonocytes (primordial cells) gonocytes Primordial germ cells – gonocytes – appeare among -

Development of Female Genital System

Reproduction Block Embryology Team Lecture 2: Development of the Female Reproductive System Abdulrahman Ahmed Alkadhaib Lama AlShwairikh Nawaf Modahi Norah AlRefayi Khalid Al-Own Sarah AlKhelb Abdulrahman Al-khelaif Done By: Khalid Al-Own, Abdulrahman Ahmed Alkadhaib & Lama AlShwairikh Revised By: Abdulrahman Ahmed Alkadhaib & Norah AlRefayi Objectives: At the end of the lecture, students should be able to: Describe the development of gonads (indifferent& different stages) Describe the development of the female gonad (ovary). Describe the development of the internal genital organs (uterine tubes, uterus & vagina). Describe the development of the external genitalia(labia minora, labia majora& clitoris). List the main congenital anomalies. Red = Important Green = Team Notes Sex Determination . Chromosomal and genetic sex is established at fertilization and depends upon the presence of Y or X chromosome of the sperm. Development of male phenotype requires a Y chromosome, and development of female phenotype requires two X chromosomes. Testosterone produced by the fetal testes determines maleness. Absence of Y chromosome results in development of the Ovary. The X chromosome has genes for ovarian development. The type of sex chromosomes complex established at fertilization determines the type of gonad differentiated from the indifferent gonads. (Testis determining factor) . The type of gonad determines the type of sexual differentiation in the Sexual Ducts and External Genitalia. Genital (Gonadal) Ridge . Appears during the 5th week. As a pair of longitudinal ridges (from the intermediate mesoderm). On the medial side of the Mesonephros (nephrogenic cord). The Primordial germ cells appear early in the 4th week among the endodermal cells in the wall of the yolk sac near origin of the allantois. -

Endometriosis in Broad Ligament: a Rare Case

International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology Chauhan R et al. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jun;6(6):2676-2677 www.ijrcog.org pISSN 2320-1770 | eISSN 2320-1789 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20172382 Case Report Endometriosis in broad ligament: a rare case Rooplekha Chauhan, Ruchita Dadhich, Bharti Sahu, Sonal Sahni* Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, NSCB Medical College, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India Received: 11 April 2017 Accepted: 08 May 2017 *Correspondence: Dr. Sonal Sahni, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Endometriosis is a relatively common entity among females presenting with abdominal pain and infertility. The endometriosis of broad ligament is a very rare yet interesting condition. In majority of the reported cases, endometriosis of broad ligament had recurrence after surgical excision. We are reporting one such case in a young nulliparous woman from Jabalpur Madhya Pradesh. Keywords: Broad ligament endometriosis INTRODUCTION The patient had undergone diagnostic laparoscopy three months back for similar complaints which clearly Anatomic defects of the broad ligament can be either demonstrated the presence of a mass within the broad congenital or acquired. The posterior broad ligament can ligament and perceived to be a case of broad ligament frequently be affected by endometriosis, especially in the fibroid. Hence patient was taken considered for presence of endometrioma.1 Peritoneal endometriosis exploratory laparotomy for acute abdominal pain. -

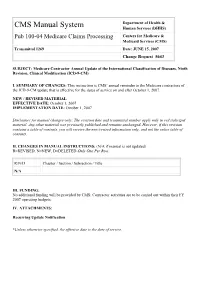

Transmittal 1269 Date: JUNE 15, 2007 Change Request 5643

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 1269 Date: JUNE 15, 2007 Change Request 5643 SUBJECT: Medicare Contractor Annual Update of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This instruction is CMS’ annual reminder to the Medicare contractors of the ICD-9-CM update that is effective for the dates of service on and after October 1, 2007. NEW / REVISED MATERIAL EFFECTIVE DATE: October 1, 2007 IMPLEMENTATION DATE: October 1, 2007 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D Chapter / Section / Subsection / Title N/A III. FUNDING: No additional funding will be provided by CMS; Contractor activities are to be carried out within their FY 2007 operating budgets. IV. ATTACHMENTS: Recurring Update Notification *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. Attachment – Recurring Update Notification Pub. 100-04 Transmittal: 1269 Date: June 15, 2007 Change Request: 5643 SUBJECT: Medicare Contractor Annual Update of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Effective Date: October 1, 2007 Implementation Date: October 1, 2007 I.