North Yukon Planning Region Resource Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

378 Yonge Street Area Details

LANDMARK CORNER OPPORTUNITY FLAGSHIP RETAIL LOCATION YONGE STREET & GERRARD STREET CORY ROSEN Goudy Real Estate Corp. VICE PRESIDENT, SALE REPRESENTATIVE Real Estate Brokerage Goudy Real Estate Corp. Real Estate Brokerage Commercial Real Estate (416) 523-7749 Sales & Leasing [email protected] 505 Hood Rd., Unit 20, Markham, ON L3R 5V6 | (905) 477-3000 The information contained herein has been provided to Goudy Real Estate Corp. by others. We do not warrant its accuracy. You are advised to independently verify the information prior to submitting an Offer and to provide for sufficient due diligence in an offer. The information contained herein may change from time to time without notice. The property may be withdrawn from the market at any time without notice. TORONTO EATON CENTRE YONGE & DUNDAS 1 YONGE STREETS RETAIL THE AURA RYERSON UNIVERSITY 378 YONGE ST. RYERSON UNIVERSITY 378 YONGE STREET AREA DETAILS Flagship retail opportunity at the corner of Yonge & Gerrard Street in the heart of Toronto. Proximity to Toronto Eaton Centre, Yonge Ryerson University is home to over 54,000 students in its various & Dundas Square, Ryerson University, and much more. 378 Yonge undergraduate, graduate and continuing education courses along Street is the point where the old Toronto meets the new Toronto - a with 3,300 faculty & staff. Ryerson University is not only expanding building designed by renowned architect John M. Lyle. but is also home to Canada’s largest undergraduate business school, the Ted Rogers School of Management. YONGE & DUNDAS THE AURA Yonge & Dundas Square and 10 Dundas is one of Toronto’s main attractions boasting open air events, a 24 multiplex theatre, 25 The Aura Condominium is Toronto’s tallest residential building, eateries, and many shops. -

Contract Award for the FG Gardiner Expressway Rehabilitation Project

PW30.3 REPORT FOR ACTION Contract Award for the F.G. Gardiner Expressway Rehabilitation Project: Section 1 – Jarvis Street to Cherry Street, Request for Tenders 1-2018, Contract No. 18ECS-TI-01GE and Amendments to Purchase Orders for Owner Controlled Insurance and External Legal Services Date: June 4, 2018 To: Public Works and Infrastructure Committee From: Chief Engineer and Executive Director, Engineering and Construction Services Chief Purchasing Officer Acting Executive Director, Corporate Finance Wards: Ward 28 (Toronto Centre-Rosedale) and Ward 30 (Toronto-Danforth) SUMMARY The purpose of this report is to: (a) advise of the results of Tender Call 1-2018 issued for Contract No. 18ECS-TI-01GE for the rehabilitation of the F.G. Gardiner Expressway (Expressway) between Jarvis Street and Cherry Street, and to request the authority to award this contract to Aecon Construction and Materials Limited in the amount of $280,840,287 which represents the "A" bid price including HST. An additional $60,000,000 plus HST will be available to the Chief Engineer and Executive Director, Engineering and Construction Services for the Project as may be required; (b) request authority to amend Purchase Order No. 6041404 with Marsh Canada Limited, for the procurement, maintenance and payment of insurance premiums associated with an Owner Controlled Insurance Program (OCIP) for Contract No. 18ECS-TI-01GE, for rehabilitation of the F. G. Gardiner Expressway Section 1 – Jarvis Street to Cherry Street, by an additional amount of $1,680,057 net of all taxes ($1,814,462 including PST); and, (c) request authority to amend Purchase Order No. -

From Toronto

,. s OUVENJR of the IROQUOIS HOTEL CORNER KING AND YORK STREETS GEO. A. GRAHAM PROPRIETOR TORONTO, CANADA GUIDE to the Points of Interest In and Around the o Queen City of the Dominion '' THE IROQUOIS HOTEL ilE IROQl'UIS i-, l)llL' of the he-.1 kno\\'n and most popular hotels in Toronto. \!any extensi\'e ami costly imprLwements h;~\·c been added to this already T modern hotel, making it Lme ,,f tht> mo-,1 desirable place-, at \\'hich to stop. The Offices, Sitting Rlll)I11 and Buffet ha\'e recei\'ed particular attention, ne\\' tile floors, new decorations and fittings have been added, making these apartments unusually attracti\'e and convenient. The Iroquois occupies a commanding positil'n on the Cl'rner of King and York Streets, in clos.: proximity to the l'nion SLttiL'Il and the \\'harves at which all the mag·nificent fleet of steamers arri\·e and depart. It stands in the \'ery heart of the busin.:ss and theatrical district, and is con\'enient to all L,f the many points of interest for which Toronto is famous. .\ complete guide of these places of attraction to all tourists and travellers maY he found in this hooklet, together \\'ith many illustrations of the -,;une. Electric cars pa-;s the door fur eYery part l)f the city and suburbs, and by the transfer s\·stcm \\'hich prevails a guest may r.:;~ch any point in the city for one fare. The cuisine i-.; first-cia.-;-; in L'\·~·ry re-.pect, and the service is characterized by neat ne-,-;, c.:lerity and civility. -

Active Transportation

Tuesday, September 10 & Wednesday, September 11 9:00 am – 12:00 pm WalkShops are fully included with registration, with no additional charges. Due to popular demand, we ask that attendees only sign-up for one cycling tour throughout the duration of the conference. Active Transportation Building Out a Downtown Bike Network Gain firsthand knowledge of Toronto's on-street cycling infrastructure while learning directly from people that helped implement it. Ride through downtown's unique neighborhoods with staff from the City's Cycling Infrastructure and Programs Unit as they lead a discussion of the challenges and opportunities the city faced when designing and building new biking infrastructure. The tour will take participants to multiple destinations downtown, including the Richmond and Adelaide Street cycle tracks, which have become the highest volume cycling facilities in Toronto since being originally installed as a pilot project in 2014. Lead: City of Toronto Transportation Services Mode: Cycling Accessibility: Moderate cycling, uneven surfaces This WalkShop is sponsored by WSP. If You Build (Parking) They Will Come: Bicycle Parking in Toronto Providing safe, accessible, and convenient bicycle parking is an essential part of any city's effort to support increased bicycle use. This tour will use Toronto's downtown core as a setting to explore best practices in bicycle parking design and management, while visiting several major destinations and cycling hotspots in the area. Starting at City Hall, we will visit secure indoor bicycle parking, on-street bike corrals, Union Station's off-street bike racks, the Bike Share Toronto system, and also provide a history of Toronto's iconic post and ring bike racks. -

Annual Report

2017 Annual Report Youth Justice. Restorative Justice. Social Justice. A Message from Table of Our Vision our Founder and Contents Youth realizing their full Executive Director potential and building safe and peaceful communities. 2017 was a year of change both in Toronto and at 03 Peacebuilders. A Message from our Founder and Executive Director What does it mean? Peacebuilders launched two new programs in 2017 as Peacebuilders envisions justice and education part of our commitment to advance restorative practices, 04 systems that are committed to helping youth, enhance youth access to justice, and work towards a more A Statistical Snapshot of Youth in especially those who are vulnerable and just and equitable society by advocating for the interests Conflict with the Law marginalized. We forsee systems that adapt to and needs of young people. young peoples’ needs—that actually engage youth divert more young people from court and keep them out and communities and make them stronger. That’s The first, our Restorative Schools Early Diversion Pilot of the criminal justice system altogether. 06 why we use restorative practices to work with Project, works in partnership with the Toronto District Restorative Justice youth and empower them to overcome conflict School Board, the Toronto Police Service, Justice for We also welcome the Toronto District School Board’s and realize their full potential. Children and Youth, and other stakeholders to intervene decision to end the School Resource Officer Program 08 at various points along the school-to-prison pipeline. and remove 36 police officers from 45 of the TDSB’s Restorative Schools We do this by using restorative practices as alternatives 112 schools. -

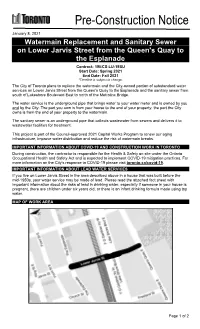

Pre-Construction Notice

Pre-Construction Notice January 8, 2021 Watermain Replacement and Sanitary Sewer on Lower Jarvis Street from the Queen's Quay to the Esplanade Contract: 19ECS-LU-19SU Start Date: Spring 2021 End Date: Fall 2021 *Timeline is subject to change. The City of Toronto plans to replace the watermain and the City-owned portion of substandard water services on Lower Jarvis Street from the Queen's Quay to the Esplanade and the sanitary sewer from south of Lakeshore Boulevard East to north of the Metrolinx Bridge. The water service is the underground pipe that brings water to your water meter and is owned by you and by the City. The part you own is from your house to the end of your property, the part the City owns is from the end of your property to the watermain. The sanitary sewer is an underground pipe that collects wastewater from sewers and delivers it to wastewater facilities for treatment. This project is part of the Council-approved 2021 Capital Works Program to renew our aging infrastructure, improve water distribution and reduce the risk of watermain breaks. IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT COVID-19 AND CONSTRUCTION WORK IN TORONTO During construction, the contractor is responsible for the Health & Safety on site under the Ontario Occupational Health and Safety Act and is expected to implement COVID-19 mitigation practices. For more information on the City's response to COVID-19 please visit toronto.ca/covid-19. IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT LEAD WATER SERVICES If you live on Lower Jarvis Street in the area described above in a house that was built before the mid-1950s, your water service may be made of lead. -

A Night at the Garden (S): a History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship

A Night at the Garden(s): A History of Professional Hockey Spectatorship in the 1920s and 1930s by Russell David Field A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Russell David Field 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-39833-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Turn out for the 50Th Nbs Alumni Reunion

TURN OUT FOR THE 50TH NBS ALUMNI REUNION Nearby Hotel and Bed & Breakfast Listings All accommodations listed are within easy walking distance of Canada’s National Ballet School. A rate comparison has been provided for your reference only. Posted rates may change. The first 4 hotels on the list are holding a limited number of rooms for NBS Alumni at discounted rates and are available on a first come, first serve basis. Hotel Style Accommodation 2010 Rate Ramada Hotel & Suites Downtown $145 300 Jarvis Street, Toronto, Ontario M5B 2C5 Reference # is: CGNBS4 Booking Deadline: March 15, 2010 Toll-free Tel: 1-800-272-6232 Local Tel: 416-977-4823 Website: www.ramada.com Best Western Primrose Hotel Single/Double $89 111 Carlton Street, Toronto, Ontario M5B 2G3 Triple $99 Toll-free Tel: 1-800-565-8865 Quadruple $109 Local Tel: 416-977-8000 Reference Code: “Alumni” or “NBS” Booking Deadline: March 23, 2010 Website: www.torontoprimrosehotel.com Town Inn Suites Hotel $89 620 Church Street, Toronto, Ontario M4Y 2G2 Toll-free Tel: 1-800-387-2755 Local Tel: 416- 964-3311 Reference Number: #190330 Booking Deadline: April 1, 2010 Website: www.towninn.com Courtyard Marriott Hotel Single/Double $169 475 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario M4Y 1X7 Toll-free Tel: 1-800-847-5075 Local Tel: 416-924-0611 Booking Deadline: March 8, 2010 Website: www.marriott.com Delta Chelsea 2 Double beds $209 33 Gerrard Street West, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1Z4 Toll-free Tel: 1-877-814-7706 Local Tel: 416-595-1975 Website: www.deltahotels.com Econo Lodge Inn & Suites Downtown 2 Queen -

130 Queens Quay E 1,915 SF for Sale: Office

Click Here for Virtual Tour! 130 Queens Quay E 1,915 SF For Sale: Office Here is where your business will grow. lennard.com 130 Queens Quay E 1,915 SF Office space located in the Waterfront Communities-The Island neighborhood in Toronto Suite Availability 819 Immediate Available Space Listing Agents 1,915 SF (approximately) Dillon Stanway Sales Representative Sale Price 416.649.5904 $2,290,000 [email protected] Condo Fees William J. Dempsey** $1,042.29 / month Partner Taxes 416.649.5940 $21,915.10 (2020) [email protected] **Broker Benefits • One of the best located and finished units in the East Tower • Top floor in east tower below the amenities. • Bright corner unit with great Views – 2 sides with full windows. • South and east facing – end of hall privacy. • Access to common amenity space with 2 high tech board rooms, lounge, large outdoor terrace & BBQ area over looking lake. • 24 hrs concierge • Bike locker room and shower room. • Secure heated storage locker available. Move In condition • Finished drop ceiling and premium carpet for sound attenuation • LED lighting throughout • 3 heat/cool zones with separate thermostats. • 5 private offices with glass side lights • 2 larger rooms with view • Separate kitchen with full fridge and dishwasher • Dividing half wall in open space • Extensively pre-wired for data and voip runs from server cupboard lennard.com 130 Queens Quay E lennard.com 130 Queens Quay E Building amenities Main Lobby Bike Storage Private Shower Facilities 130 Queens Quay E Common areas Private Meeting Rooms Rooftop -

For Lease | 411 Church Street

ForRetail Lease 411 Church Street Overview Located just steps away from Yonge and College, Ryerson University and across the Street from Maple Leaf Gardens, 411 Church Street is a strong retail development with 572 residential units and over 7,000 square feet of premium retail space. With an abundance of public transit in 411 CHURCH STREET close proximity including the College Subway stop, the area has become one of the most accessible in the city. Significant residential density has welcomed a breadth of new retailers and consumers into area making the Church and Wellesley Village one of the most desirable neighbourhoods to live, work, and play in Toronto. The ground floor offers three exceptional retail units all featuring substaintial frontage onto Church Street. At the corner of Church and Wood is a signature restaurant opportunity with operable windows and a prominent patio opportunity on Wood Street. With soaring ceiling heights of 21 FT, 411 Church Street is a premium retail opportunity for high-profile restaurant, fitness, quick service food, and CHURCH STREET health and wellness tenants. YONGE STREET Property details RETAIL 1: 3,839 SF RETAIL 2: LEASED RETAIL 3: LEASED AVAILABLE: Immediately TERM: 10 years NET RENT: Contact Listing Agent ADDITIONAL RENT: $20.55 PSF (2021) Highlights • Shadow-anchored by Loblaws, LCBO, and Joe Fresh at Maple Leaf Gardens • Strong pedestrian traffic highlighted by a significant Ryerson University popula- tion comprised of 43,000 students (growth of 7,000 students over the last 5 years) • Incredible 21 FT ceiling heights and a modern glass façade offering signature branding • Direct access to shipping and receiving for all units • Unit 1 – signature corner restaurant opportunity with patio on Wood Street • Unit 2 / 3 – small format retail spaces with ample frontage on Church Street Within 1km radius Demographics Source: Statistics Canada 77,135 169,348 Population Daytime Population $65,167 44,572 Avg. -

Ctc Computer Training Centre Ctc Computer Training Centre Is Located at 4 King Street, Suite 1520, Toronto, Ontario, M5H 1B6

4 King Street West, Suite 1520, Toronto, Ontario M5H 1B6 416-214-1090 Tel: 416-214-6353 Fax: 201 City Centre Drive, Suite 404, Mississauga, Ontario L5B2T4 905-361-5144 Tel: 905-361-5143 Fax: Local Hotels/Information - Toronto Training Locations - Toronto 1. ctc Computer Training Centre ctc Computer Training Centre is located at 4 King Street, Suite 1520, Toronto, Ontario, M5H 1B6. This is at King and Yonge Street located at the King Street subway stop. Our Phone Number is (416) 214-1090 Directions from Toronto International Airport to Toronto ctc offices at 4 King Street West. 1 Begin at TORONTO LESTER B PEARSON IN and go Northeast for 300 feet 2 Turn right on Airport Rd and go East for 0.5 miles 3 Turn left on ramp and go East for 900 feet 4 Bear right on Highway 427 and go Southeast for 7 miles 5 Continue on Gardiner Expy and go East for 9 miles 6 Exit Gardiner Expy via ramp to Yonge St and go Northeast for 0.2 miles 7 Turn left on Yonge St and go North for 0.4 miles 8 Turn left on King St W and go West for 150 feet 2. SUBWAY STOPS If you leave your car at the Yorkdale or Wilson Subway stops close to the 401, and come down on the Subway, you should get off at the King Street stop - we are right there. If you drive all the way, you would take 427 south from the airport and east onto the Gardner expressway. Get off at the Bay/York exit. -

Waterfront Toronto Launches

WATERFRONT TORONTO UNVEILS DESIGN SUBMISSIONS FOR JARVIS SLIP Foot of Jarvis Street to become key component in network of world renowned waterfront public spaces Toronto, January 18, 2008 – Waterfront Toronto has selected three distinguished teams to participate in a design competition to enhance the public space at the Jarvis Slip. The teams selected to participate in the design competition are: • Janet Rosenberg & Associates • Claude Cormier architectes paysagistes inc. • West 8 + DTAH Waterfront Toronto will hold a public exhibition of completed design proposals from January 21-25, 2008 at Metro Hall (55 John Street), and a review by a four member jury of prominent arts and design professionals leading to a February 01, 2008 announcement of the winner. “This is yet another opportunity for Waterfront Toronto to distinguish the public realm on the waterfront and in so doing, continue to build a great waterfront for Toronto” said John Campbell, Waterfront Toronto’s President and CEO. The intersection of Lower Jarvis Street and Queens Quay is a key gateway to the future East Bayfront community. Waterfront Toronto is sponsoring this Invited Design Competition to produce an innovative design and bring a fresh, new perspective to the one-acre site at the foot of Lower Jarvis Street. Designs are expected to readily accommodate large scale gatherings and performances without compromising its day- to-day informal usage. This space is seen as a complementary component of the public realm in the East Bayfront precinct, which will also include a revitalized Queens Quay, Sherbourne Park, Aitken Place Park, as well as the water’s edge promenade and public streets.