Eye on Endemics: a Closer Look at Our Local Bird Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

A Comprehensive Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny of the New World

YMPEV 4758 No. of Pages 19, Model 5G 2 December 2013 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2013) xxx–xxx 1 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev 5 6 3 A comprehensive species-level molecular phylogeny of the New World 4 blackbirds (Icteridae) a,⇑ a a b c d 7 Q1 Alexis F.L.A. Powell , F. Keith Barker , Scott M. Lanyon , Kevin J. Burns , John Klicka , Irby J. Lovette 8 a Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, and Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 9 55108, USA 10 b Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA 11 c Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA 12 d Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA 1314 15 article info abstract 3117 18 Article history: The New World blackbirds (Icteridae) are among the best known songbirds, serving as a model clade in 32 19 Received 5 June 2013 comparative studies of morphological, ecological, and behavioral trait evolution. Despite wide interest in 33 20 Revised 11 November 2013 the group, as yet no analysis of blackbird relationships has achieved comprehensive species-level sam- 34 21 Accepted 18 November 2013 pling or found robust support for most intergeneric relationships. Using mitochondrial gene sequences 35 22 Available online xxxx from all 108 currently recognized species and six additional distinct lineages, together with strategic 36 sampling of four nuclear loci and whole mitochondrial genomes, we were able to resolve most relation- 37 23 Keywords: ships with high confidence. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

GHNS Booklet

A Self-Guided Tour of the Biology, History and Culture of Graeme Hall Nature Sanctuary Graeme Hall Nature Sanctuary Main Road Worthing Christ Church Barbados Phone: (246) 435-7078 www.graemehall.com Copyright 2004-2005 Graeme Hall Nature Sanctuary. All rights reserved. www.graemehall.com Welcome! It is with pleasure that I welcome you to the Graeme Hall Self-Guided Tour Nature Sanctuary, which is a part of the Graeme Hall of Graeme Hall Nature Sanctuary Swamp National Environmental Heritage Site. A numbered post system was built alongside the Sanctuary We opened the new visitor facilities at the Sanctuary to trails for those who enjoy touring the Sanctuary at their the public in May 2004 after an investment of nearly own pace. Each post is adjacent to an area of interest US$9 million and 10 years of hard work. In addition to and will refer to specific plants, animals, geology, history being the last significant mangrove and sedge swamp on or culture. the island of Barbados, the Sanctuary is a true community centre offering something for everyone. Favourite activities The Guide offers general information but does not have a include watching wildlife, visiting our large aviaries and detailed description of all species in the Sanctuary. Instead, exhibits, photography, shopping at our new Sanctuary the Guide contains an interesting variety of information Store, or simply relaxing with a drink and a meal overlooking designed to give “full flavour” of the biology, geology, the lake. history and culture of Graeme Hall Swamp, Barbados, and the Caribbean. For those who want more in-depth infor- Carefully designed boardwalks, aviaries and observation mation related to bird watching, history or the like, good points occupy less than 10 percent of Sanctuary habitat, field guides and other publications can be purchased at so that the Caribbean flyway birds are not disturbed. -

The Birds of BARBADOS

BOU CHECKLIST SERIES: 24 The Birds of BARBADOS P.A. Buckley, Edward B. Massiah Maurice B. Hutt, Francine G. Buckley and Hazel F. Hutt v Contents Dedication iii Editor’s Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgements xv Authors’ Biographies xviii List of tables xx List of figures xx List of plates xx The Barbados Ecosystem Introduction 1 Topography 3 Geology 7 Geomorphology 7 Pedology 8 Climate, weather and winds 9 Freshwater and wetlands 13 Vegetation and floristics 14 Non-avian vertebrates 16 Freshwater fishes 16 Amphibians 17 Reptiles 17 Mammals 18 Historical synopsis 19 Prehistoric era 19 Colonial and modern eras 20 Conservation concerns 23 Avifauna 25 Historical accounts 25 Museum collectors and collections 26 Field observations 27 Glossary 27 vi Frequency of Occurrence and Numerical Abundance 28 Vagrancy 29 The Species of Barbados Birds 30 Vicariance, Dispersal and Geographical Origins 36 Historical Changes in the Barbados Avifauna 38 Extinction versus Introduction 39 The Role of Vagrancy 39 Endemism 42 Molecular Insights 42 Seabirds 45 Shorebirds 45 Land-birds 46 Habitat Limitations 46 Core Barbados Species 47 Potential Additions to the Barbados Avifauna 47 Annual North- and Southbound Migration 48 Elevational Migration 49 Recovery of Ringed Birds 49 Radar and Mist-net Studies of Migration 50 Inter-island Movements by Ostensibly Resident Land-birds 52 Austral and Trinidad & Tobago Migrants 53 Overwintering Migrants 54 Oversummering Migrants 54 Fossil and Archaeological Birds 55 Research Agenda 56 Systematic List Introduction 59 Taxonomy -

FIELD GUIDES BIRDING TOURS: Lesser Antilles 2013

Field Guides Tour Report Lesser Antilles 2013 Mar 30, 2013 to Apr 14, 2013 Jesse Fagan I hadn't run this tour for three years so I was a little bit curious about how things had changed on "the islands." I am always nervous about the connecting flights, lost baggage (LIAT don't let us down!), and general logistics on this logistically complicated tour. However, we seem to have it down to a science after years of practice, and LIAT has gotten better! It was a great tour in 2013. We saw all of the Lesser Antilles' endemics very well including great looks at the tough ones: Grenada Dove (my closest and best encounter ever; and at the last minute!), Imperial Parrot (chasing a pair through the Syndicate forest and eventually having them right over our heads!), St. Lucia Black-Finch (at our feet; and it does have pink feet!), and White-breasted Thrasher (twelve, count 'em twelve! on the island of Martinique). It was an adventure and I want to thank this most excellent group for doing it with me. I can't wait to see you all again. More a bird of the Greater Antilles, the White-crowned Pigeon reaches the northern Lesser Antilles --Jesse aka Mot (from Lima, Peru) islands of Antigua and Barbuda, where it is quite common. (Photo by tour participant Greg Griffith) KEYS FOR THIS LIST One of the following keys may be shown in brackets for individual species as appropriate: * = heard only, I = introduced, E = endemic, N = nesting, a = austral migrant, b = boreal migrant BIRDS Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, and Waterfowl) WEST INDIAN WHISTLING-DUCK (Dendrocygna arborea) – A number along Antigua Village Ponds. -

Bird List E = Endemic EC = Endemic to Caribbean ELA= Endemic to Lesser Antilles ES = Endemic Subspecies NE = Near Endemic NES = Near Endemic Subspecies

Lesser Antilles Prospective Bird List E = Endemic EC = Endemic to Caribbean ELA= Endemic to Lesser Antilles ES = Endemic Subspecies NE = Near Endemic NES = Near Endemic Subspecies West Indian Whistling Duck Dendrocygna arborea EC Black-bellied Whistling Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Greater Scaup Aythya marila Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Green-winged Teal Spatula crecca American Wigeon Mareca americana White-cheeked Pintail Spatula bahamensis Northern Pintail Spatula acuta Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus Feral Rock Pigeon Columba livia Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto Scaly-naped Pigeon Patagioenas squamosa EC White-crowned Pigeon Patagioenas leucocephala Grenada Dove Leptotila wellsi E Bridled Quail-Dove Geotrygon mystacea EC Ruddy Quail-Dove Geotrygon montana Zenaida Dove Zenaida aurita EC Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata Common Ground Dove Columbina passerina Red-billed Tropicbird Phaethon aethereus mesonauta White-tailed Tropicbird Phaethon lepturus White-tailed Nightjar Hydropsalis cayennensis manati St.Lucia Nightjar Antrostomus (rufus) otiosus E Antillean Nighthawk Chordeiles gundlachii ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 ● Fax (520) 320 9373 Lesser -

Patterns of Shiny Cowbird Parasitism in St. Lucia and Southwestern Puerto Rico ’

The Condor92:461469 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1990 PATTERNS OF SHINY COWBIRD PARASITISM IN ST. LUCIA AND SOUTHWESTERN PUERTO RICO ’ WILLIAM POST CharlestonMuseum, 360 Meeting St., Charleston,SC 29403 TAMMIE K. NAKAMURA Department of Zoology, Colorado State University,Fort Collins, CO 80523 ALEXANDER CRUZ Department of EPO Biology, Universityof Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309 Abstract. The density of Shiny Cowbirds (Molothrus bonariensis)in lowland St. Lucia and Martinique is about six individuals/km2, compared to 49/km2 in lowland southwestern Puerto Rico. Their distribution in the Antilles may be related to agriculturethat provides food for adults, as much as to availability of suitable hosts. In St. Lucia, four of eight potential host specieswere parasitized. Black-whiskeredVireos ( Vireoaltiloquus) and Yellow Warblers (Dendroicapetechia) accountedfor 90% of all parasitized nests. Patterns of par- asitism did not match host availability in either SW Puerto Rico or St. Lucia. In St. Lucia only Gray Kingbirds (Tryannus dominicensis)rejected >75% of experimental cowbird eggs. Gray Kingbirds, Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos),and Greater Antillean Grack- les (Quiscalusniger) were rejectersin Puerto Rico. The successof parasitizedYellow Warbler nests was higher in Puerto Rico than in St. Lucia. Cowbird parasitism reduced Yellow Warbler nest successin St. Lucia, but not Puerto Rico. Comparisons with Puerto Rico indicate that neither hosts nor cowbirds in St. Lucia have evolved defenses or counter- defensesduring a 40-year period. Key words: Brood parasitism; host selection;egg rejection;Shiny Cowbird: Molothrus bonariensis;St. Lucia; Puerto Rico; Martinique. INTRODUCTION objectives were to: (1) contrast the distribution The Shiny Cowbird (Molothrusbonariensis), a and abundance of Shiny Cowbird populations in generalist brood parasite, has spread rapidly St. -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 32:11–16. 2019 Phylogeography and historical demography of Carib Grackle (Quiscalus lugubris) Meghann B. Humphries Maribel A. Gonzalez Robert E. Ricklefs Photo: Leticia Soares The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology jco.birdscaribbean.org ISSN 1544-4953 RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 32:11–16. 2019 www.birdscaribbean.org Phylogeography and historical demography of Carib Grackle (Quiscalus lugubris) Meghann B. Humphries1,2, Maribel A. Gonzalez3, and Robert E. Ricklefs1,4 Abstract We assessed the phylogeography of the Carib Grackle (Quiscalus lugubris), whose distribution includes eight subspe- cies in the Lesser Antilles and northern South America. We used the geographic distribution of variation in the mitochondrial genes ATPase 6 and ATPase 8 to assess the demographic history of the species and degree of concordance between phylo- genetic relationships and subspecies assignments. We recovered a single haplotype in Guyana and French Guiana, which was shared by some samples from Trinidad, but Trinidad also hosts a second mitochondrial clade separated by 2.9% sequence di- vergence. Similarly, Venezuela is home to two sympatric clades separated by 3.6% divergence. Genetic relationships of island populations appeared largely discordant with currently described subspecies. Keywords colonization, demography, introduced species, phylogeography, Quiscalus lugubris Resumen Filogeografía y demografía histórica de Quiscalus lugubris—Evaluamos la filogeografía de Quiscalus lugubris, cuya distribución incluye ocho subespecies en las Antillas Menores y el norte de Sudamérica. Utilizamos la distribución geográfica de la variación en los genes mitocondriales ATPasa 6 y ATPasa 8 para evaluar la historia demográfica de la especie y el grado de concordancia entre las relaciones filogenéticas y las asignaciones de subespecies. -

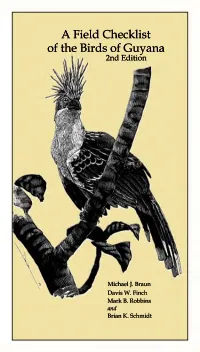

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003). -

Behavioural Innovation and the Evolution of Cognition in Birds

BEHAVIOURAL INNOVATION AND THE EVOLUTION OF COGNITION IN BIRDS Sarah Elizabeth Overington Department of Biology McGill University, Montreal September 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © Copyright: Sarah E. Overington, 2010 DEDICATION For my son and my father, who crossed paths for a few short months this year: Kai James, born February 18, and Murray James, died April 10. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The insight, creativity and humour of my PhD supervisor, Louis Lefebvre, is behind all of the work in this thesis, and I thank him immensely for his role in shaping me into the researcher I am today. He encouraged me to develop strong hypotheses and predictions, but also to pay attention to the cues of my stubborn experimental subjects in Barbados and to adjust my work to make it feasible. Louis allowed me the freedom to collaborate with researchers at many other institutions, thus satisfying my urge to approach a very broad thesis question using as many relevant techniques as possible. Neeltje Boogert has been my foremost collaborator and a great friend from the start of this degree. My thesis would not exist were it not for her discussions, comments, very thorough editing and laughter throughout the process. She also contributed data to this thesis, from catching birds in Barbados and measuring skulls in museum collections to conducting analyses. She is a great teacher and scientist, and I look forward to our continued collaboration. Julie Morand-Ferron acted as a mentor and friend, guiding me through my PhD and providing great ideas and discussions.