Civil Procedure: Pre-Trial & Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 1

Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 1 VISIT US AT SASSNET .COM Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 2 VISIT US AT SASSNET .COM Cowboy Chronicle The Cowboy February 2017 Page 3 Chronicle CONTENTS 4-7 COVER FEATURE Editorial Staff Canadian National Championships Skinny 8 FROM THE EDITOR Editor-in-Chief Skinny’s Soapbox Misty Moonshine 9-13 NEWS Riding for the Brand ... Palaver Pete Retiring Managing Editor 14, 15 LETTERS & OPINIONS Tex and Cat Ballou Editors Emeritus 16-19 COSTUMING CORNER Kudos to the Gentlemen of SASS Costuming Adobe Illustrator 20-31 ANNUAL REPORTS Layout & Design Hot Lead in Deadwood ... Range War 2016 Mac Daddy 32-37 GUNS & GEAR Dispatches From Camp Baylor Graphic Design 38-43 HISTORY Square Deal Jim A Botched Decade ... Little Known Famous People Advertising Manager 44-48 PROFILES (703) 764-5949 • Cell: (703) 728-0404 Scholarship Recipient 2016 ... Koocanusa Kid [email protected] 49 SASS AFFILIATED MERCHANTS LIST Staff Writers 50, 51 SASS MERCANTILE Big Dave, Capgun Kid Capt. George Baylor 52, 53 GENERAL STORE Col. Richard Dodge Jesse Wolf Hardin, Joe Fasthorse 54 ADVERTISER’S INDEX Larsen E. Pettifogger, Palaver Pete Tennessee Tall and Rio Drifter 55-61 ARTICLES Texas Flower My First Shoot ... Comic Book Corner Whooper Crane and the Missus 62, 63 SASS NEW MEMBERS The Cowboy Chronicle is published by 64 SASS AFFILIATED CLUB LISTINGS The Wild Bunch, Board of Directors of (Annual / Monthly) The Single Action Shooting Society. For advertising information and rates, administrative, and edi to rial offices contact: Chronicle Administrator 215 Cowboy Way • Edgewood, NM 87015 (505) 843-1320 • FAX (505) 843-1333 email: [email protected] Visit our Website at http://www.sassnet.com The Cowboy Chronicle SASSNET.COM i (ISSN 15399877) is published ® monthly by the Single Action Shooting Society, 215 SASS Trademarks Black River Bill ® ® Cowboy Way, Edgewood, NM 87015. -

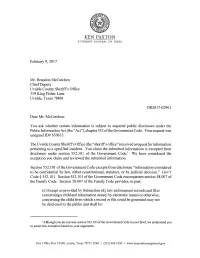

Scanned Document

KEN PAXTON ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS February 9, 2017 Mr. Brandon Mccutchen Chief Deputy Uvalde County Sheriffs Office 339 King Fisher Lane Uvalde, Texas 78801 OR2017-02901 Dear Mr. McCutchen: You ask whether certain information is subject to required public disclosure under the Public Information Act (the "Act"), chapter 552 ofthe Government Code. Your request was assigned ID# 650633. The Uvalde County Sheriffs Office (the "sheriffs office") received a request for information pertaining to a specified incident. You claim the submitted information is excepted from disclosure under section 552.101 of the Government Code. 1 We have considered the exception you claim and reviewed the submitted information. Section 552.101 of the Government Code excepts from disclosure "information considered to be confidential by law, either constitutional, statutory, or by judicial decision." Gov't Code§ 552.101. Section 552.101 of the Government Code encompasses section 58.007 of the Family Code. Section 58.007 of the Family Code provides, in part: ( c) Except as provided by Subsection ( d), law enforcement records and files concerning a child and information stored, by electronic means or otherwise, concerning the child from which a record or file could be generated may not be disclosed to the public and shall be: 1Although you do not raise section 552.10 I of the Government Code in your brief, we understand you to assert this exception based on your arguments. Post Office Box 12548, .Austin, Texas 78711-2548 • (512) 463-2100 • www.texasattomeygeneral.gov Mr. Brandon McCutchen - Page 2 (1) if maintained on paper or microfilm, kept separate from adult files and records; (2) if maintained electronically in the same computer system as records or files relating to adults, be accessible under controls that are separate and distinct from controls to access electronic data concerning adults; and (3) maintained on a local basis only and not sent to a central state or federal depository, except as provided by Subchapters B, D, and E. -

John B. Armstrong John B

Official State Historical Center of the Texas Rangers law enforcement agency. The Following Article was Originally Published in the Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine The Texas Ranger Dispatch was published by the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum from 2000 to 2011. It has been superseded by this online archive of Texas Ranger history. Managing Editors Robert Nieman 2000-2009; (b.1947-d.2009) Byron A. Johnson 2009-2011 Publisher & Website Administrator Byron A. Johnson 2000-2011 Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame Technical Editor, Layout, and Design Pam S. Baird Funded in part by grants from the Texas Ranger Association Foundation Copyright 2017, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, TX. All rights reserved. Non-profit personal and educational use only; commercial reprinting, redistribution, reposting or charge-for- access is prohibited. For further information contact: Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 2570, Waco TX 76702-2570. John B. Armstrong John B. Armstrong Texas Ranger and Pioneer Rancher by Chuck Parsons Foreword by Tobin Armstrong Afterword by Elmer Keaton College Station, Texas: Texas A & M University Press, 2006 Photos, 150 pages, hardcover $20 ISBN 978-1-58544-533-0 Of the hundreds who have served as Texas Rangers, only thirty are enshrined in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame. One, John Armstrong, is the subject of this biography. Incredibly, no major work has been written on this great Ranger until now. (This is also true of the majority of the Rangers in the Hall of Fame.) John Wesley Hardin was the deadliest gunfighter in the history of the Old West. -

Give Thanks. Their Own Game and Building a Negras Across the River from and to Become a Legitimate Triumphantly on His Grave

1100 Hamilton Herald-News TThursday,hursday, NNovemberovember 119,9, 22020020 HHN short and need to go up?” asked councilman George Beard. THIS WEEK IN TEXAS HISTORY Council “I feel like we are,” Polster From page 5 replied. “We need somebody pro- Smartest outlaw makes a dumb mistake nization had hoped to have com- fessional to do this.” pleted before the next youth fair. Slone asked if there were oth- er companies that offer this ser- lor-made chaps with a crimson and in June 1876 he arrested a hand, and within months the She said issues with wir- ing and repairs as well as fewer vice, and Polster said he would By Bartee Haile waist sash. Wearing a buckskin nine members of the Fisher deputy was in charge after his broaden his search. jacket with gold embroidery, he gang in a raid on the Pendencia. host ran afoul of the law he events because of the pandemic Determined to succeed have depleted funds but HCJLA “Forty-five thousand is a lot topped off the expensive ward- Tying the prisoners to their sad- was supposed to enforce. The of money for someone to come where his predecessor had has helped with expenses. robe with a white sombrero also dles for the ride to Eagle Pass, reformed rustler was assured tell us we’re losing money,” failed, Texas Ranger Capt. Lee “Also, we have a contingent trimmed in precious metal and the Ranger warned Fisher’s of election when voters went to Slone said. Hall arrested King Fisher on featuring a gold snake hatband. -

February 24 2014

FROM THE PRESIDENT Junie Ledbetter, Jay R. Old & Associates, PLLC, Austin Dear TADC Friends, Winter has been a busy time for TADC, with more to come for members of all ages and interests. BOARD MEETING: TADC conducted its second board meeting for the 2013 - 2014 term in Austin on the first major ice day on a freezing January Friday. In spite of bad weather, most were able to overcome travel challenges and attend the meeting, continue work on projects at hand, and enjoy a friendly dinner with several justices from the Texas Supreme Court and their wives. PROJECTS & NEW MEMBERS: Some of the projects now underway include planning for programming in your area, review and evaluation of pertinent interim charges posted by the legislature, updating publications and the TADC website, and discussion of membership initiatives. If you know someone interested in joining TADC, please pass this generous offer on to them: upon payment of membership dues ($295 for a 5 year lawyer), the new member will be entitled to a $500 credit on the seminar of their choice, whether in Washington DC in April, Couer d’Alene Idaho in July, or in San Antonio in September. Applications are print-ready on the TADC website, and you can send them in today. (http://www.tadc.org/become-a-member/) Given the many benefits of membership, this is quite a bargain. LOCAL PROGRAMS: Mitch Moss again encouraged El Paso TADC members to gather in January for combined CLE on “Legal Writing for the Re-wired Brain” and happy hour with other local attorneys. -

October 2020 San Antonio, TX 78278-2261 Officers Hello Texican Rangers

The Texas Star Newsletter for the Texican Rangers A Publication of the Texican Rangers An Authentic Cowboy Action Shooting Club That Treasures & Respects the Cowboy Tradition SASS Affiliated PO Box 782261 October 2020 San Antonio, TX 78278-2261 Officers Hello Texican Rangers President A.D. 210-862-7464 [email protected] Vice President Burly Bill Brocius October 10th was a very busy day at 210-310-9090 the Texican Rangers! [email protected] During the shooters meeting, we handed out the 2019-2020 annual category Secretary awards. 49 Rangers qualified for an Tombstone Mary award. This figure is up from last year’s 210-262-7464 numbers. Considering that the range was [email protected] closed for 2 months the increase is impressive. Panhandle Cowgirl was the Treasurer overall ladies champion and Alamo Andy General Burleson was the overall men's champion. 210-912-7908 After the shooters meeting, 49 shooters [email protected] shot the 5 stages, and 13 shooters shot the match clean. This match is the first match Range Master for the annual category awards for the 2020-2021 season. Colorado Horseshoe After the match, all the targets and 719-231-6109 tables were put away for the winter. [email protected] Thank you to all who stayed and helped tear down the range! Communications Before you know it, January 2021 will Dutch Van Horn be here, and it will be time to pay dues. In 210-823-6058 November, Tombstone Mary will email [email protected] your 2021 waiver. It is a huge help for as many members as possible, to sign the waiver and mail it to our P.O. -

Gunfighter Capitalof Thewest

TEXAS: Gunfighter Capital of theWest Texans had fought Comanches, Mexicans and Yankees, and that fighting spirit carried over after the Civil War for better and for worse—10 of the deadliest 15 Old West shootists operated in the Lone Star State By Bill O’Neal The poisonous atmosphere of Reconstruction produced such gunfighters as native Texan John Wesley Hardin, left , who ascosa, Texas, was already known as the away, still clutching his Winchester. Valley pursued at age 15 killed a former slave. “Cowboy Capital of the Plains” when Woodruff, but Lem stopped him in his tracks with a slug to The late Hardin, above, took a one of the deadliest saloon shootouts the left eye. fatal bullet from John Selman, in frontier history exploded at the The gunfire awakened Jesse Sheets, owner of the North Star who was born in Arkansas but town’s main intersection. On Saturday restaurant next door. When he unwisely peered out the back made his reputation in Texas. evening, March 20, 1886, four cowboys door of the North Star, either Chilton or Lang gunned him More than a few publications, from the nearby LS Ranch—Ed King, down. Even as Sheets dropped with a hole in his forehead, (see two below) played up the Fred Chilton, Frank Valley and John Lang—attended a baile two bullets ripped toward Chilton’s gun flash. The rounds exploits of hardnosed Hardin. Tat a dive just west of town. These LS riders frequently tore into Chilton’s chest. He handed his gun to Lang and caroused in Tascosa and had made a number of enemies; died. -

Scanned Document

KEN PAXTON ATTORNEY GENERAL OP TEXAS February 13, 2018 Chief Deputy Brandon Mccutchen Uvalde County Sheriffs Office 339 King Fisher Lane Uvalde, Texas 78801 OR2018-03371 Dear Chief Deputy Mccutchen: You ask whether certain information is subject to required public disclosure under the Public Information Act (the "Act"), chapter 552 ofthe Government Code. Your request was assigned ID# 695696. The Uvalde County Sheriffs Office (the "sheriff s office") received a request for specified information pertaining to a specified incident. You claim the submitted information is excepted from disclosure under section 552.108 of the Government Code. We have considered the exception you claim and reviewed the submitted information. Initially, we note the sheriffs office has only submitted an incident report pertaining to the specified incident. To the extent information responsive to the remainder of the request existed on the date the sheriffs office received the request, we assume you have released it. See Open Records Decision No. 664 (2000) (if governmental body concludes no exceptions apply to requested information, it must release information as soon as possible). If you have not released any such information, you must do so at this time. See Gov't Code §§ 552.301(a), .302. Section 552.108(a) of the Government Code excepts from disclosure "[i] nformation held by a law enforcement agency or prosecutor that deals with the detection, investigation, or prosecution of crime ... if: (1) release of the information would interfere with the detection, investigation, or prosecution ofcrime." Id § 552. l 08(a)(l ). Generally, a governmental body claiming section 552.108(a)(l) must explain how and why the release of the requested information would interfere with law enforcement. -

Chronology of Significant Events 1835-1935

TX01e01.qxp 1/25/2008 9:01 AM Page 15 Chronology of Significant Events 1835-1935 1835 Texas provisional government formed at San Felipe and independence declared by several assemblies, notably one at Goliad on December 20. 1840 Notorious Texas gunman Robert A. Clay Allison was born in Tennessee. Allison killed at least five men before his violent life ended in a wagon accident on July 1, 1887, in Pecos, Texas. Joseph L. Hood, first sheriff of Bexar County, was killed in a melee with Comanche chiefs within the Town Council House during the course of peace negotiations (prior to April 18). 1841 Renowned black lawman Bass Reeves was born this year or perhaps the previous year in Arkansas, then removed with the Reeves family to Grayson County, Texas. Reeves was apparently the first black deputy U.S. marshal to be appointed west of the Mississippi. Charles W. Jackson, a participant in the Regulator-Moderator War, was killed. A year earlier, a judge sent to try Jackson for killing Joseph G. Goodbread was himself killed near Pulaski, Texas, after fleeing for his life. Thomas D. Yocum, proprietor of the Yocum Inn in the Big Thicket country of East Texas, was executed by a Regulator posse on information that Yocum had murdered several people. 1843 John V. Morton, first sheriff of Fort Bend County, was killed by his former deputy, George W. Pleasants (February 7). 15 TX01e01.qxp 1/25/2008 9:01 AM Page 16 16 200 TEXAS OUTLAWS 1844 Texas Ranger George W. Arrington was born in Alabama. 1847 Approximate birth year of Longhair Jim Courtright, probably an Illinois native who moved to Fort Worth in about 1875, then served from time to time in a series of law enforcement positions before starting his own detective service, described by detractors as nothing more than an extortion operation. -

A Reading Guide for Live Oak County, Texas - Kurt House, Originally Printed 1977, Revised 1980 and 2018

A Reading Guide for Live Oak County, Texas - Kurt House, originally printed 1977, revised 1980 and 2018 Introduction The purpose of this bibliography is to simplify the study of relevant topics in Live Oak County, Texas. From my experience through many years of study, it is somewhat difficult to locate all the various sources of the county because it requires much research and is not available in a single document. By necessity therefore, this is a temporary list which will be revised from time to time as the author discovers more sources. I have endeavored to keep the style readable, so as to insure its comprehension and appeal to the county population as a whole, and while I have tried to make many of the primary sources available in the Live Oak County Library, the cost and effort to maintain all such sources prevents my donation of all of them. Some of the key articles however, such as that by Price and Gunther (1942) concerning the change of south Texas grasslands to the brush country, I have photocopied and donated to the county library, as well as a copies of this guide which were also placed in the libraries of George West and Three Rivers. The important articles are indicated by an asterisk(*) and are now available in the county library at George West, Texas. I invite the contributions of others who know of books, periodicals, newspaper articles and other sources regarding the history of our area and I will assist anyone who is unable to obtain enough material to his or her liking. -

Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine

Official State Historical Center of the Texas Rangers law enforcement agency. The Following Article was Originally Published in the Texas Ranger Dispatch Magazine The Texas Ranger Dispatch was published by the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum from 2000 to 2011. It has been superseded by this online archive of Texas Ranger history. Managing Editors Robert Nieman 2000-2009; (b.1947-d.2009) Byron A. Johnson 2009-2011 Publisher & Website Administrator Byron A. Johnson 2000-2011 Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame Technical Editor, Layout, and Design Pam S. Baird Funded in part by grants from the Texas Ranger Association Foundation Copyright 2017, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, TX. All rights reserved. Non-profit personal and educational use only; commercial reprinting, redistribution, reposting or charge-for- access is prohibited. For further information contact: Director, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, PO Box 2570, Waco TX 76702-2570. TEXAS RANGER DISPATCH Magazine Rangers Today Visitor Info History Research Center Hall of Fame Student Help Family History News Movie Review: Click Here for A Complete Index Texas Rangers to All Back Issues Review by Chuck Parsons Dispatch Home Visit our nonprofit Museum Store! Several years ago, the Hall of Fame and Museum staff learned that Dimension Films was planning a new Texas Contact the Editor Ranger movie to be released in 1999. It was to showcase rising star Dylan McDermott of television's The Practice. The script writers had purchased the rights to the 1962 book Taming the Nueces Strip based on Texas Ranger George Durham's reminiscences of Capt. -

TDHCA Board Book

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS BOARD MEETING OF MARCH 13, 2003 Michael Jones, Chair C. Kent Conine, Vice-Chair Beth Anderson, Member Shadrick Bogany, Member Vidal Gonzalez, Member Norberto Salinas, Member MISSION TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS TO HELP TEXANS ACHIEVE AN IMPROVED QUALITY OF LIFE THROUGH THE DEVELOPMENT OF BETTER COMMUNITIES BOARD MEETING TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY AFFAIRS 507 Sabine, Board Room, Fourth Floor, Austin, Texas 78701 March 13, 2003 11:00 a.m. A G E N D A CALL TO ORDER, ROLL CALL Michael Jones CERTIFICATION OF QUORUM Chair of Board PUBLIC COMMENT The Board will solicit Public Comment at the beginning of the meeting and will also provide for Public Comment on each agenda item after the presentation made by department staff and motions made by the Board. The Board of the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs will meet to consider and possibly act on the following: EXECUTIVE SESSION Michael Jones Consultation with Attorney Pursuant to Sec. 551.071(2), Texas Government Code - Appeal by Enclave at West Airport, Houston, Multifamily Mortgage Revenue Bonds and Low Income Housing Tax Credits, 02-464 OPEN SESSION Michael Jones Action in Open Session on Items Discussed in Executive Session Item 1 Presentation, Discussion and Possible Approval of Minutes of Board Michael Jones Meetings of February 13, 2003 Item 2 Action on Appeal by The Enclave at West Airport, Houston, Michael Jones Multifamily Mortgage Revenue Bonds and Low Income Housing Tax Credits, 02-464 Item 3 Presentation, Discussion and Possible Approval of Financial Items: C.